April 16, 2017

‘Cause Freedom Ain’t Free: Freedom Summer Movement in 1964 Mississippi

Winner of the Spring 2017 StMU History Media Awards for

Article with the Best Introduction

What is your vote worth to you? Is it worth the half-hour it takes to stand in line while you wait to fill out your ballot? The five dollars in gas it costs to drive to your local polling station? The two years’ worth of complacency knowing that you were a “good citizen” that “did their part?” Further still, how would you react if someone tried to take the right to vote away from you? Threatened to take away your job if you just tried to register to vote? Or tried to burn down your home? Harm your family? Starve your community? Would you still have the courage to go and register to vote?

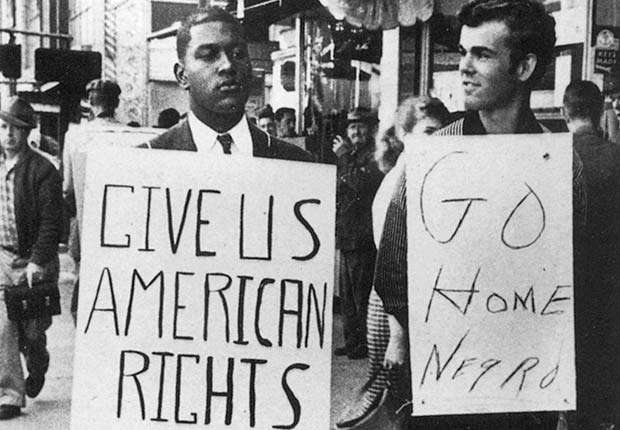

For Mississippi’s black community in the 1960’s, these were not rhetorical questions. Despite the passage of the 15th Amendment in 1870, by 1961 less than 12% of Mississippi’s black population was registered to vote, with many counties reporting rates of less than 1%.1 These numbers can be attributed to the efforts of the white supremacist government of Mississippi, its upper and middle classes, and its public servant core, all of whom actively worked to oppress the black population and prevent them from voting.

"I assert that the Negro race is an inferior race. The doctrine of white supremacy is one which, if adhered to, will save America." - United States Senator James O. Eastland from Ruleville Mississippi, 19452

It is difficult to articulate the fear, almost hysteria, that the white community had towards an increase in political participation by Mississippi’s black population, a phobia that was largely rooted in the paranoia that increased political involvement by the black community would overturn the current Southern way of life.3 This fear was reflected in the words and actions of the white community and their leadership, and manifested itself in a variety of measures designed to bar black citizens from exercising their right to vote.

For example, in order for citizens to register to vote in some Mississippi counties, they were required to pass a literacy or interpretation test, which was graded by exclusively white, highly prejudiced staff. In other counties, prohibitive poll taxes were put in place that prevented members of the impoverished black communities from voting. Elsewhere, entire lists of black citizens who tried to register were published as a matter of public record. These individuals often suffered severe reprisals for simply trying to register. For instance, it was common for white employers to fire black employees for attempting to register to vote. The Ku Klux Klan, which rose to prominence in Mississippi in 1964, conducted a campaign of intimidation and night raids against members of the black community; these raids frequently resulted in beatings, lynchings, firebombing of homes and churches, and murder.4

Given the enormous danger they faced, the resilience of those who stood firm in the face of adversity speaks volumes about the character of the activists who tried to end these discriminatory practices. In the years leading up to 1964, a grassroots movement organized by the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), led by Robert Moses, had started to gain traction in encouraging black citizens to register to vote, especially in the town of Greenwood.5 In reprisal for the increase in black citizens registering to vote, the local government cut off the commodities program in Greenwood, which was a government surplus program that provided food to in-need, poor, and rural communities. The black population in Greenwood faced the very real prospect of starvation until comedian Dick Gregory learned of what was happening and used his own money to fly in food and supplies. Gregory’s action garnered substantial attention from the national media, which planted the seed in the minds of SNCC organizers for the idea that would eventually become the Mississippi Summer Project, more popularly known as Freedom Summer.6

The idea behind the Mississippi Summer Project was to challenge the white supremacist establishment by empowering the black community through education, voter registration, and community building. The Council of Federated Organizations (COFO) was comprised of Mississippi branches of several civil rights organizations, including the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), and SNCC. The project, which was organized primarily by SNCC veterans, bused in over a thousand college volunteers from all over the country to Mississippi, with plans of utilizing the increased manpower to further its voter registration and education goals, as well as generating national media attention to the predominantly black movement through national interest in the white volunteers.7

Much was accomplished during the course of the Mississippi Summer Project. Volunteers and COFO members established community centers and “Freedom Schools,” which provided both children and adults in the black community with a political education as well as courses common to a traditional high school curriculum. In addition to going door-to-door and advocating voter registration to black communities, the Mississippi Summer Project also registered black citizens on mock polling lists to show that they wanted to register to vote in the official election, but they were simply afraid or unable to do so. Finally, the COFO held their own “Freedom Primary” concurrently with the state’s Democratic Party, with the intent of challenging the Democratic Party’s representatives in two Mississippi districts with representatives from their own “Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP),” including sharecropper Fannie Lou Hamer and Reverend John Cameron.8 Later in April, two other candidates were also nominated, Victoria Jackson Gray and James Monroe Houston, raising the total number of candidates to four.9

This last effort arguably led to the culmination of the Freedom Summer Movement. In August of 1964, the MFDP sent a delegation of 68 members to the Democratic National Convention in Atlantic City, Georgia, in an attempt to unseat the official Democratic delegation by claiming that the official delegation did not represent the collective will of Mississippi, since the black populace had been denied the right to vote. The MFDP successfully sued for a hearing before the convention’s Credentials Committee, and were granted the right to present their case on the convention floor before the national media.10

"I don't know how anybody can stop what they're doing on the Freedom Party. I think it's very bad, and I wish that I could stop it. I've tried, but I haven't been able to. Last night I couldn't sleep. About 2:30 I waked up...I do not believe I can physically and mentally carry the responsibilities of the world, and the Niggras, and the South. I thought about it a good deal this morning." -President Lyndon B. Johnson, on the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party11

President Lyndon B. Johnson, at the time running for presidential election, took the actions of the MFDP very seriously, largely out of fear that the overtures of the MFDP could potentially split the Democratic Party in the South, possibly costing him the election. Wanting to nip this movement in the bud before it could affect the election, Johnson sent representatives to the convention to ensure that the delegates from the MFDP would not be officially seated at the convention, including his future Vice President, Hubert Humphrey. In particular, President Johnson was so worried about the galvanizing effect of the testimony from one of the movement’s leaders, the sharecropper Frannie Lou Hamer, that he decided to interrupt the live national broadcast of her testimony before the Credentials Committee with an impromptu press conference, where he proceeded to announce that it was the nine-month anniversary of the shooting of former President Kennedy and Texas Governor John Connally. This political move ended up backfiring, however, as the story of the President’s actions spread and Frannie Lou’s testimony was rebroadcast multiple times in the following days.12 Nevertheless, the political pressure placed on the convention by Johnson and the white establishment bore fruit, and instead of unseating the Mississippi delegation, the MFDP was offered a compromise of two seats in the delegation. The MFDP unanimously rejected this compromise, and Johnson went on to be elected to the presidency.

Overall, while the project suffered numerous setbacks, including the kidnapping and murder of three of its volunteers as well as its failure to unseat the Mississippi Democratic delegation, the Mississippi Summer Project made significant strides in altering cultural attitudes towards equal voting rights across the country, especially in the rural black populations of Mississippi. The reform movement’s greatest success was that it arguably laid the groundwork for the Voting Rights Act of 1964, a law which placed voting in seven southern states under federal supervision and abolished literacy tests as a requirement for voting registration.13

Often, we as Americans are fond of spouting such aphorisms like “freedom is never truly free,” but rarely do we truly understand the gravity of our words. Freedom always has a cost, and the freedoms that we enjoy today are often earned on the backs of those who fought and struggled to ensure their existence. Often these people are forgotten by history. For every Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. that reaches our history textbooks, there’s a Robert Parris Moses. For every Rosa Parks, there’s a Fannie Lou Hamer. If you are like many Americans, these names are probably unfamiliar to you–but that’s alright. Because their very real struggles, the blood, sweat, and tears that they poured into the cause that they championed, have undoubtedly bettered the moral fabric of our society, even if their name will never be remembered by your average American.

- Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, “Statistics of Negro and White Voter Registration in the Five Congressional Districts of Mississippi,” from The Freedom Summer Sourcebook (Madison: Wisconsin Historical Society, 2013), 189-192. ↵

- “Mississippi Subversion of the Right to Vote,” From the Freedom Summer Sourcebook, (Madison:Wisconsin Historical Society, 2013), 195. ↵

- Freedom Summer, directed by Stanley Nelson, (United States: WGBH Educational Foundation, 2014), Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nBgnyNFufR4, Documentary. ↵

- UXL Encyclopedia of U.S. History, 2009, s.v., “Freedom Summer,” by Sonia Benson, Daniel E. Brannen Jr., and Rebecca Valentine, From Gale Virtual Reference Library (accessed April 13, 2017), 592. ↵

- Charles Payne, I’ve Got the Light of Freedom: The Community Organizing Tradition in the Mississippi Freedom Struggle (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995), 244-245. ↵

- Freedom Summer, directed by Stanley Nelson, (United States: WGBH Educational Foundation, 2014), Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nBgnyNFufR4, Documentary. ↵

- UXL Encyclopedia of U.S. History, 2009, s.v., “Freedom Summer,” by Sonia Benson, Daniel E. Brannen Jr., and Rebecca Valentine, From Gale Virtual Reference Library (accessed April 13, 2017), 593. ↵

- “Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee News Release dated March 20, 1964,” (Atlanta:Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, 1964), 30, from The Freedom Summer Sourcebook (Madison:Wisconsin Historical Society, 2013), 189-192. ↵

- “Freedom Candidates, Mississippi, April 12, 1964, from The Freedom Summer Sourcebook (Madison:Wisconsin Historical Society, 2013), 289-292. ↵

- Freedom Summer, directed by Stanley Nelson (United States: WGBH Educational Foundation, 2014), Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nBgnyNFufR4, Documentary. ↵

- Freedom Summer, directed by Stanley Nelson, (United States: WGBH Educational Foundation, 2014), Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nBgnyNFufR4, Documentary. ↵

- Freedom Summer, directed by Stanley Nelson (United States: WGBH Educational Foundation, 2014), Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nBgnyNFufR4, Documentary. ↵

- Freedom Summer, directed by Stanley Nelson (United States: WGBH Educational Foundation, 2014), Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nBgnyNFufR4, Documentary. ↵