March 26, 2020

Der Löwe von Afrika and the Battle of Tanga

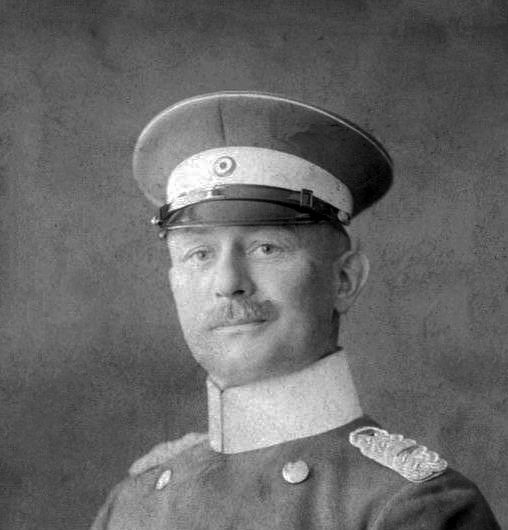

The First World War is mostly known for static trench warfare set mostly on the European continent. However, the war spread to its colonies and its many spheres of influence that also quickly became involved in the affair. Colonial warfare during WWI was very fluid and comprised of skirmishes, guerrilla tactics, and special forces operations with the occasional significant engagements. One of those engagements was the East African Campaign, which started near the beginning of the war and lasted all the way to the end of the war. Here is the story of that campaign from the Germans’ perspective and from the men who led them, namely that of a German General named Paul Emil von Lettow-Vorbeck. He was the German equivalent to Lawrence of Arabia and was as effective. Lettow-Vorbeck is regarded as one of the greatest guerrilla tacticians in military history, and a father to modern-day special forces.

Lettow-Vorbeck came from a small, noble Pomerania household. Coming from a family with a military tradition, he joined the Prussian Cadet Corps. Lettow-Vorbeck went to the military academies at Potsdam and Berlin, where he graduated in 1890 top of his class. He then entered into the Imperial German Army, the “Deutsches Heer.” Lettow-Vorbeck took part in the German expeditionary forces in China, which was part of the Eight-Nation Alliance. During the Chinese uprising against foreign influence, he fought to put down the Boxer Rebellion between 1899 to 1901. Between 1904 and 1908, Lettow-Vorbeck took part in the Herero Wars, which was a series of colonial wars between the German Empire and the Herero people in German Southwest Africa, in present-day Namibia.1

In January of 1914, Lettow-Vorbeck arrived in Dar-es-Salaam, a port city in one of Germany’s colonies on the African continent, called German East Africa, now present-day Tanzania. Lettow-Vorbeck was promoted to the rank of General of the Infantry, equivalent to a Major General in the U.S. military army. He was tasked to protect the colony from external and internal threats.

Lettow-Vorbeck took charge of the colonial defense called the Schutztruppe, or protection force troopers in English. This army was primarily composed of the Askari and a handful of German officers, making the German East African Schutztruppe the first racially integrated army in modern history. “Here in Africa we are all equal, the better man will always outwit the inferior and the color of his skin does not matter,” Lettow-Vorbeck famously said when asked about his army after the war.2 It was a small force, but sufficient for peace enforcement and security purposes since part of the Berlin Conference was the agreement that the colonies will remain neutral towards each other during European wars.3

When Lettow-Vorbeck assumed command, the Schutztruppe was hopelessly behind modern military units—using outdated line tactics in battle and equipment, with rifles of 1871 models while also using smoky powder cartridges. Later, after enlisting the help of a police sergeant major, he managed to modernize the Schutztruppe to the best that their resources allowed. Then, in August of the same year, the powder keg in Europe was ignited in the aftermath of the assassination of the Archduke Ferdinand of Austria. After receiving a letter from the German Kaiser Wilhelm II, Lettow-Vorbeck was ordered to fully mobilize his forces. Lettow-Vorbeck started to prepare for war with the limited troops and supplies he had at his disposal. He decided to try to divert as many resources of his enemies to himself rather than turn them over to the empire and Kaiser. His forces when counting the Schutztruppe, police forces, marines from the SMS Konigsberg, a light cruiser stationed at the colony, and non-combatants added to 14,000 personnel. 4

Lettow-Vorbeck and the colonial governor, Dr. Heinrich Schnee, constantly clashed on how they would use their military force in the upcoming war on their colony’s horizon. Schnee wished to be defensive and only put the Schutztruppe where they were needed. In contrast, Lettow-Vorbeck wanted to attack the neighboring colonies using his small force for employing raids and guerrilla tactics.5

Soon reports came that two English light cruisers, the HMS Astraea and the Pegasus, were firing at a wireless tower near the shore of the colony.6 After receiving these reports, Lettow-Vorbeck disobeyed the governor’s orders, and sent troops into British East Africa and attacked the critical Uganda Railway and other military targets.

By November and after nearly two months of small-scale engagements and skirmish on the borders, Lettow-Vorbeck received word that Expeditionary Force B, an assault force consisting of British African and Indian troops, were on converted ocean liners, and slowly steaming towards Tanga. The reason for the slow pace was that the transports were only capable of seven knots while being escorted by two light cruisers. At the same time, Expeditionary Force C attacked the Usambara Railway near Mount Kilimanjaro. This was an attempt to end the campaign quickly in order to send to remaining British troops to back Europe. Under short notice, Lettow-Vorbeck sent Major Goerg Kraut to defend the railway.7 At the same time, Lettow-Vorbeck himself took charge of the defense of the city, as his forces were arriving mostly by narrow gauge trains and trucks. The British were unloading troops and equipment and demanded the surrender of the city. A German lieutenant ended up tricking the British under the belief that he was receiving the terms of their surrender from his superiors and that the bay had been heavily mined. This allowed Lettow-Vorbeck’s forces a few days for preparation. With that, Lettow-Vorbeck managed to muster a force of a thousand troops to defend against a total force of 8000 British Indian and African expeditionary troops.8

The Battle of Tanga started at midnight on November 2, 1914. The British were confident in a victory due to their overwhelming superiority and believing that they would seize the city by daybreak. Force B arrogantly committed themselves to a full-frontal assault, divided into two forces, and pushed to the city. The northern assault force consisted of Indian troops and pushed through mostly farmland being largely successful. They managed to reach the city center and pulled far ahead to the southern assault force. The southern assault force had to fight through woodlands as well as encounter fierce resistance and counterattacks. This caused the southern assault force to retreat, in fear of being outflanked and surrounded. The northern assault force had to fall back in order to protect their retreating allies. By November 5, the British forces made a full retreat.9

A nickname of the Battle of Tanga is the Battle of Bees because, during the assault, the British disturbed several beehives, which did not affect the assault in any significant way, but it surely did not help.10 Initially, there was a joke that the bees were fighting for the German side of the conflict. However, the bees started to attack the Germans as they chased the retreating British forces. During the hasty retreat, the attacking forces left equipment and supplies such as modern weapons, ammunition, and food, which was later distributed among the German forces. The Askari took it as a great honor and respect as the received the new equipment from their superiors.11

The first significant engagement of the East African Campaign was a German victory and a British defeat with the number of casualties at nearly a thousand troops. One brigade lost half of its officers. The battle is considered in British history as one of their greatest military failures. The Kaiser himself noted that “the brilliant victory at Tanga has pleased me [Kaiser Wilhelm] greatly.”12 Lettow-Vorbeck’s forces received relatively light casualties compared to the British with only 147 troops being killed or wounded. Those numbers are misleading because in terms of percentages, the Germans had a casualty rate of 14.7% of their defending force, and the British had 12.4% of the attacking force. And this was a common theme throughout the campaign.

A few months later, after another victory at the Battle of Jasini, Lettow-Vorbeck realized that the forces could not continue fighting in large-scale open combat with the British. So, he went back to his guerrilla tactics, using the advantage that his forces’ small size gave him. He often used his forces to outflank the enemy and disrupted supplies lines. Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck continued to fight till November 25, 1918, two weeks after the end of the war. He returned to Germany as a war hero, known as the last German General, to surrender.

- “Paul Emil Von Lettow-Vorbeck: German Army Officer (1870-1964) – Biography and Life,” (PeoplePill. Accessed February 26, 2020. https://peoplepill.com/people/paul-von-lettow-vorbeck/. ↵

- Robert Gaudi, African Kaiser: Paul Von Lettow-Vorbeck and the Great War in Africa, 1914-1918 (Place of publication not identified: C HURST & CO PUB LTD, 2017), 2. ↵

- Paul Emil, MY REMINISCENCES OF EAST AFRICA: the German East Africa Campaign in World War One – a Generals… Memoir. (S.l.: LULU COM, 2019), 7. ↵

- Paul Emil, My Reminiscences of East Africa: the German East Africa Campaign in World War One – a Generals… Memoir (S.l.: LULU COM, 2019), 17. ↵

- Robert Gaudi, African Kaiser: Paul Von Lettow-Vorbeck and the Great War in Africa, 1914-1918 (Place of publication not identified: C HURST & CO PUB LTD, 2017),182. ↵

- Paul Emil, My Reminiscences of East Africa: the German East Africa Campaign in World War One – a Generals… Memoir (S.l.: LULU COM, 2019), 21. ↵

- Robert Gaudi, African Kaiser: Paul Von Lettow-Vorbeck and the Great War in Africa, 1914-1918 (Place of publication not identified: C HURST & CO PUB LTD, 2017), 176. ↵

- Paul Emil, My Reminiscences of East Africa: the German East Africa Campaign in World War One – a Generals… Memoir (S.l.: LULU COM, 2019), 33. ↵

- Robert Gaudi, African Kaiser: Paul Von Lettow-Vorbeck and the Great War in Africa, 1914-1918 (Place of publication not identified: C HURST & CO PUB LTD, 2017), 201. ↵

- Robert Gaudi, African Kaiser: Paul Von Lettow-Vorbeck and the Great War in Africa, 1914-1918 (Place of publication not identified: C HURST & CO PUB LTD, 2017), 198. ↵

- Robert Gaudi, African Kaiser: Paul Von Lettow-Vorbeck and the Great War in Africa, 1914-1918 (Place of publication not identified: C HURST & CO PUB LTD, 2017), 198. ↵

- Byron Farwell, The Great War in Africa: 1914-1918 (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1989), 179. ↵

Tags from the story

Battle of Tanga

Paul Emil von Lettow-Vorbeck

World War I

Seth Roen

I am an International & Global Studies major with a double minor in History and Military Science at St. Mary’s University, Class of 2023. I want to live an interesting life with adventure. I enjoy writing and learning about the world around me both past and present.

Author Portfolio Page