October 28, 2021

From Slave to Author: The Story of Harriet Jacobs

Could you live for seven years in a space that is only nine feet long, seven feet wide, and three feet high, without fresh air or natural light? I think all of us would agree that it would be virtually humanly impossible for a person to live like that for that many years. However, Harriet Jacobs knew that if she wanted to gain freedom for herself and her children, she had to do what was virtually impossible. Her uncle Philip, who was a very skilled carpenter, fixed up a little crawlspace in the roof where she could live. The conditions, as I mentioned, were deplorable: mice and rats ran over her bed, and she could sleep only by sleeping on one side.1 You may be wondering why Jacobs had to hide and from whom. I am going to tell you the reason, but most importantly, let me tell you the inspiring story of Harriet Jacobs.

Harriet Jacobs was born in Edenton, North Carolina in the fall of 1813, and she was the slave of Margaret Horniblow until 1825. Horniblow bequeathed Jacobs to her three-year-old niece Mary Norcom; so her father became Jacobs’ master.2 Dr. James Norcom, a despicable and terrible man, was Jacobs’ abusive master and tormentor. Dr. Norcom was obsessed with Jacobs and wanted her complete physical and sexual control. She suffered a lot of sexual and verbal abuse when she was serving Dr. Norcom, because he was very possessive of her. The way he treated her made Mrs. Norcom jealous, which raised gossip around the neighborhood about the situation. From person to person, Jacobs’ situation came to the attention of a distinguished gentleman named Samuel Sawyer, who was a white attorney and who was not married. Sawyer became curious about Harriet and started asking questions about her master and the situation she was going through. Jacobs, as a fifteen-year-old, felt flattered to have the attention and sympathy of this educated and expressive single man. She knew that Sawyer was a generous man and that he would be willing to buy her freedom. She was desperate, and the thought of her future children being brought up under the eye of her evil master worried her to death. Jacobs was naïve, and thought that when Dr. Norcom found out that she was going to have a baby, he would sell her and she would finally be free from him. Even though she was born into slavery, she soon realized how badly and unfairly slaves were treated, and how the law and the government denied them any rights or liberties. It was almost impossible to imagine living the rest of her life at the hands of a tyrant, without truly achieving her deepest desires and without getting to know the world beyond slavery and the plantations.3

Jacobs indeed became pregnant with Sawyer’s child, and he made a promise to her and to her grandmother to take care of their newborn and buy their freedom. The good news did not last long because when Jacobs told her master that she was pregnant, he was very mad at her and started saying horrendous things to her. “You obstinate girl! I could grind your bones to powder! You have thrown yourself away on some worthless rascal. You are my slave and shall always be my slave. I will never sell you, that you may depend upon.” Jacobs’ hope for freedom vanished as she heard those harsh words, and all she had longed for died away.4

Not too much later after her first child was born, Jacobs was carrying another baby, and this time it was with a little girl. She named her Louisa. Her happiness and excitement were rapidly replaced with concern and distress; in slavery, women suffered more than men. She wanted to protect Louisa and keep her away from that terrible world. Her children were extremely afraid of Dr. Norcom, and whenever he would come around, they hid their faces and asked why the evil man came to visit them so often, and it seemed to them that he wanted to hurt them. He did not dare touch her children, but they had learned to fear him.5 Moreover, Samuel Sawyer did not keep his promise to buy his children’s and Jacobs’ freedom; so she had to take the matter into her own hands. She had to escape, but she did not have a solid plan; so her uncle Philip managed to get her a place of concealment in her grandmother’s house. There, starting in 1835, she spent her days sewing clothes and toys for her children and reading the Bible; there is nothing much to do under those conditions, but Jacobs never lost faith or hope.6 She had no space to move her limbs or sleep comfortably, and to her last days, she would suffer pains from having spent so much time without properly stretching her body.

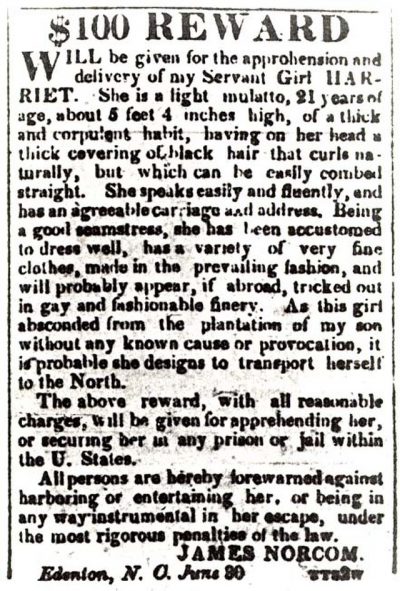

Dr. Norcom’s threat was still pertinent. He published an ad in the newspapers announcing a reward for the capture of Harriet Jacobs. Besides everything that was happening at the moment, what comforted her was the joy and sadness in her children’s voices, because she did not want anything in the world other than to see their eager eyes and to talk to them for at least one more time. Through a small hole, she could peek at Louisa and Joseph happily playing, and that warmed her heart. After five years, Louisa was sent to Brooklyn, New York, to some relatives of Sawyer’s. Mother and daughter saw each other before her departure and spent the night together. Even though she was very young, she was clever and observant. She did not hesitate to embrace her mother and ask why she had to hide. Louisa promised that she would not tell anyone about her mother’s whereabouts, and she kept her promise.7

One evening, Jacobs’ friend Peter came to her and said “Your time has come. I have found a chance for you to go to the Free States.” Jacobs found it so hard to believe at first, but everything was arranged and ready, and all that was left to do was to hear her answer. She was so scared of Dr. Norcom and his control over her family. Peter said, with sincere conviction, that she had to take this opportunity because a chance like this would not repeat itself again and that she did not have to fear for Joseph, because he could easily be sent to her when she arrived at the Free States, and Louisa and grandma were already safe.8

It was 1842, and the night had finally come. Jacobs later mentioned that she could not remember how she got to the dock where the boat for the escape was waiting for her because her mind and heart were racing. When she was in the vessel, she was kindly greeted by the captain, who was an old white man. He guided her to a little cabin, and there was her old friend Fanny. She was so astonished to see Jacobs there, because everyone thought that she had disappeared. They fell into each other’s arms and could not resist the tears anymore. The sound of the sobs caught the captain’s attention and he told them that for their safety, they should remain on the low, and he would tell them, if they passed another ship, that they should find cover. It was hard for Jacobs to trust the white men on the boat, but she quickly saw that their intentions were pure and that they took good care of both. As Jacobs had, so also Fanny had had to hide for a long time from her master and leave her children, who were sold to another master, but Fanny lost total contact with them. They could not express their excitement at finally seeing the sunshine and the sea while their boat smoothly sailed into the Chesapeake Bay. They evaded any type of danger, even with people patrolling the sea and those patrolling the city streets for any fugitive slaves. Happily, ten days after their departure, they arrived in Philadelphia.9

As they landed, she started looking around and thanked the captain. Truth be told, she did not stop being grateful for his services ever, because it could not be put into words how much that meant to her. After that, they went to buy gloves and veils for her and Fanny in some shops in the city. It was difficult, at first, for Jacobs to walk and to move her body, but while she was on board, she rubbed her limbs with saltwater and that greatly helped her mobility. Keep in mind that everything was new to her, because she had been seven years in concealment, and she did not want to raise any suspicion about her and about where she had come from. The noise and movement of the city surprised her, but she thought that Philadelphia was a wonderful place.10 When they arrived in New York City, Jacobs was overwhelmed by the crowd of men shouting “Carriage, ma’am?” After getting a carriage and driving for some time, Fanny was dropped off in a boarding house where the Anti-Slavery Society offered her a home. Then, Jacobs went to Brooklyn to reunite with her daughter Louisa at Mr. Sawyer’s cousin’s house. She was very nervous because it had been two years since she last saw her daughter, before she had been sent to the North. Unable to contain her emotion, Jacobs pressed Louisa to her heart, then pulled her away to take a good look at her and held her close. At last, they were together.11

Jacobs had one thing on her mind that still troubled her, and that was that she needed to get a job. Most of the employers required a recommendation from a family she had served before, but for obvious reasons, she could not do that. An acquaintance of hers told her about a lady that was looking for a nanny for her baby, and asked for someone who was a mother and had experience with kids. The lady’s name was Mrs. Willis, and she was from England, which gave Jacobs some kind of relief, because she had heard that the English were not as racist as Americans. Mrs. Willis asked her some questions, and she then gave her the job. It was hard for Jacobs to trust Mr. and Mrs. Willis because of the trauma she had had with white people. But they were kind and benevolent and they gained Jacobs’ trust and friendship. She enjoyed taking care of their baby because it reminded her of when Louisa and Joseph were younger. Because of going up and down the stairs, Jacobs’ limbs began to give her so much pain that she was not able to perform her duties correctly anymore. Instead of firing her, as any other employer would do, Mrs. Willis made an appointment with a physician. Jacobs really appreciated this kind gesture from Mrs. Willis and knew that she had a big heart. Even though they were growing closer, Jacobs could not bring herself to tell her mistress that she was a fugitive slave, but would do it eventually.12

She still needed to get Joseph to the North, so she sent a letter to her grandmother telling her to send Joseph to Boston, and she would meet him there so her children and Jacobs could finally be reunited. It was early in the morning when she heard a knock on the door, and when she went to get it, Joseph was happily waiting for her. Jacobs could not put into words what she felt when she saw her child.13 Before getting her family together again, she secured a house for Louisa and Joseph to live with her in Boston, while she was working for the Willis’s. They had the life they always longed for, but there was still that feeling of not being completely and legitimately free people.

Mr. and Mrs. Willis were exceptionally kind to her; they gave her a home and the hope to start a new life. Eventually, Mrs. Willis gained Jacobs’ trust and she confide in her with her deepest secret, and Mrs. Willis promised her that she would help her. Unfortunately for Jacobs, her old master was still looking for her and he still represented an imminent threat for Jacobs and her children. Mrs. Willis intended to buy Jacobs’ freedom, and that is what she did in 1852.14 Jacobs called Mrs. Willis her friend, a term she did not use for everyone. The nightmare and times of uncertainty were all over! She was deeply grateful and felt like the weight from her shoulders had been lifted. She was a free black woman in the free city, and her children were too.

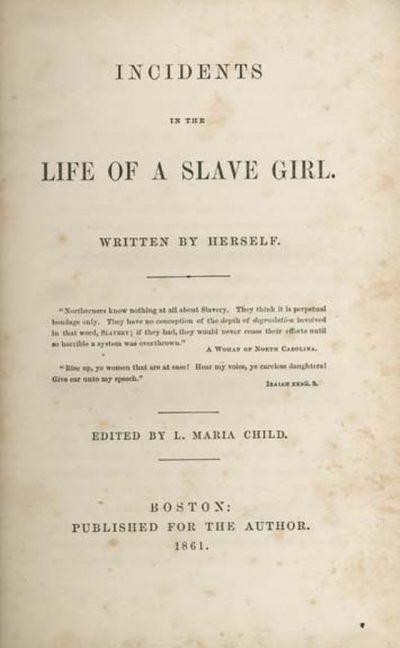

In 1853, she began to write her autobiography, in which she describes her experience as a slave. She was the first woman to write about being a fugitive slave in the United States. She wanted to take part in the anti-slavery movement and tell the world and other slaves about her story of suffering and resilience, but it was so painful for her to remember the past and she was not a writer.15 The help of her friend and editor Lydia Maria Child was undoubtedly a great relief for Jacobs while she was writing her story, and she made it possible to get Jacobs’ work published. By the summer of 1857, she had completed her book and was published in late 1861 in Boston. Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl is one of the great achievements of nineteenth-century American literature, in which Jacobs draws in her audience with her opening sentence, “Reader, be assured this narrative is no fiction.”16

- Harriet A. Jacobs and Lydia Maria Francis Child, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, Wright American Fiction, 1851-1875 (The author, 1861), 173. ↵

- William L. Andrews, “Harriet A. Jacobs (Harriet Ann), 1813-1897”, Documenting the American South, https://docsouth.unc.edu/fpn/jacobs/bio.html/. ↵

- Harriet A. Jacobs and Lydia Maria Francis Child, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, Wright American Fiction, 1851-1875 (The author, 1861), 84-86. ↵

- Harriet A. Jacobs and Lydia Maria Francis Child, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, Wright American Fiction, 1851-1875 (The author, 1861), 90-91. ↵

- Harriet A. Jacobs and Lydia Maria Francis Child, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, Wright American Fiction, 1851-1875 (The author, 1861), 122. ↵

- John Sekora, “Harriet Jacobs,” in Salem Press Biographical Encyclopedia, (Salem Press, 2021). ↵

- Harriet A. Jacobs and Lydia Maria Francis Child, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, Wright American Fiction, 1851-1875 (The author, 1861), 210-212. ↵

- Harriet A. Jacobs and Lydia Maria Francis Child, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, Wright American Fiction, 1851-1875 (The author, 1861), 227. ↵

- Harriet A. Jacobs and Lydia Maria Francis Child, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, Wright American Fiction, 1851-1875 (The author, 1861), 237-241. ↵

- Harriet A. Jacobs and Lydia Maria Francis Child, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, Wright American Fiction, 1851-1875 (The author, 1861), 242. ↵

- Harriet A. Jacobs and Lydia Maria Francis Child, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, Wright American Fiction, 1851-1875 (The author, 1861), 249-250. ↵

- Harriet A. Jacobs and Lydia Maria Francis Child, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, Wright American Fiction, 1851-1875 (The author, 1861), 254-255. ↵

- Harriet A. Jacobs and Lydia Maria Francis Child, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, Wright American Fiction, 1851-1875 (The author, 1861), 261. ↵

- William L. Andrews, “Harriet A. Jacobs (Harriet Ann), 1813-1897”, Documenting the American South, https://docsouth.unc.edu/fpn/jacobs/bio.html/. ↵

- Jean Fagan Yellin, Harriet Jacobs: A Life (New York: Perseus Books Group, 2004) ↵

- John Sekora, “Harriet Jacobs,” in Salem Press Biographical Encyclopedia, (Salem Press, 2021) ↵

Tags from the story

American Slavery

Harriet Jacobs

Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl

Ariette Aragon

Hola a todos! My name is Ariette Aragón and I am from Chinandega, Nicaragua. I am a Business Management major, Class of 2025 at St. Mary’s University. I love photography, going to the beach, hiking, listening to music, hanging out with my friends, and meeting new people.

Author Portfolio Page