October 1, 2019

Impaled: The Impossible Story of Phineas Gage

It was September 13th, 1848 at 4:30pm. Phineas Gage, a twenty-five year old American railroad construction foreman, was busy preparing the ground for railroad tracks to be laid down in Cavendish, Vermont.1 As he worked with his crew on this bright and sunny day, nobody was aware that it was about to take an incredible turn for the worse. What occurred this day would go down in history, not only as one of psychology’s most revolutionary case studies, but also as an unbelievably surreal story of sheer luck.

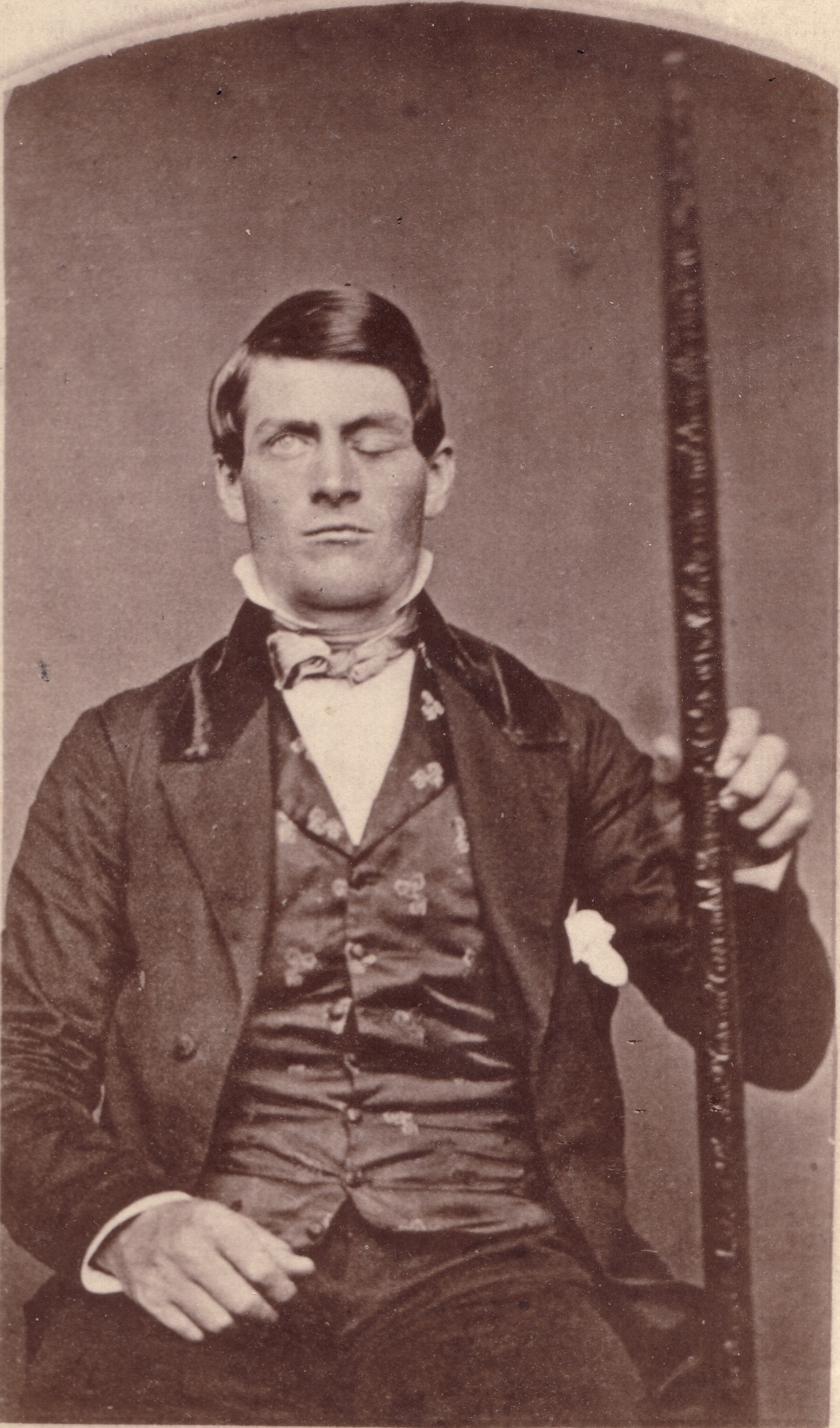

At the time, Phineas Gage was employed by contractors working closely with Rutland and Burlington Railroad.2 As the foreman of a group of men who were constructing the railroad bed, he was a “great favorite with the men in his gang,” known by many to have “work skills and personal qualities that led him to the rapidly expanding and potentially rewarding railroad construction industry.”3 On this particular day, Gage and his crew happened to be detonating outcrop, or a large rocky formation, right outside of Cavendish. Packing explosive powder into drill holes, Gage used his tamping iron, a tool similar to a crowbar, to tightly “tamp down” or pack the powder so the rock could be excavated. Tapering slightly at one end, Gage’s tamping iron was specifically made for him by a local blacksmith, measuring three feet and seven inches long, one and one-quarter inches in diameter on the larger end, and weighing 13 and one-quarter pounds.4 As Gage went through the repetitive motions of his job, tamping rod in hand, something went wrong. Little did Gage know that this was the last time he would truly be himself.

As the hand-crafted iron made contact with the ground, seemingly like normal, a premature explosion occurred. In a split second, the iron violently drove up through Gage’s left cheek, passing through the frontal cortex of his brain behind his left eye, and exiting destructively through his skull. The force was so powerful that it threw his body back, the tamping iron landing twenty-five to thirty yards behind him.5 This incident alone should have killed him immediately, but just minutes later, after being assisted by his crew, Gage sat up and rode unsupported in an oxcart with some fellow workers to his current residence at the Cavendish Hotel. He was able to see, hear, speak, and even write in a journal that he had which was infinitely more than what was expected of him after the incident. He was completely aware of what had occurred as well as what was going on around him at the time. With the intensity of the trauma Gage had just experienced, it was a miracle that he was conscious at all, let alone able to perform basic functions. Taking a seat next to his landlord, Gage waited for Dr. John Martin Harlow, the town physician, to come to his much needed assistance.6

Upon arriving at the hospital, Gage was still profusely bleeding from both his head and inside his mouth, but despite the obvious injuries, he continued to carry the conversation and avoided any complaining. For the first couple of days Dr. Harlow was treating him, he had no complications and his future looked extremely promising. At this point, Gage had survived the event itself, the effects of going into shock, profuse blood loss, as well as intense brain swelling. However, things soon took a turn for the worse; although his wounds were cleaned on the surface and dressed in bandages, his brain was still exposed to the outside world where bacteria was bound to find it. Just days later, Phineas developed an infection, enduring both “delirious spells” and a “foul-smelling liquid” coming from the wound. With the little medical treatment that he received due to the lack of knowledge in the medical field during the 1800s, it was very likely that Phineas Gage’s infection would prove to be fatal. At the time, scientists were not even remotely aware that bacteria can cause infection. Two weeks after the accident, Gage began to develop an abscess underneath the skin directly above his eye. As his health quickly declined, Dr. Harlow continued giving him the best treatment he knew how to provide, lancing the abscess to drain the fluid.7 Despite the likeliness of fatality, Gage defied the odds once again, eventually recovering fully.

Although physically he looked much the same as before, though with a few scars and the loss of sight in his left eye, Phineas was completely different than the hard-working, easy-going man that he was before. His friends, family, and even his doctor saw his personality traits dramatically transformed. He became extremely ignorant and developed an intense stubbornness and temper. He used a lot of vulgar language, which was not something that he did before. He also became a persistent liar and could not be trusted by anyone, especially his coworkers. Because the frontal lobes of the brain control emotion, Gage suffered from “a lack of balance between his emotions and his intellectual propensities” due to the damage received.8

After his release from the hospital, Gage attempted to go back to construction work with Rutland and Burlington Railroad. However, with his drastic and unreliable personality changes, his coworkers did not trust him and they expressed that he was no longer fit for the job. During this time, Dr. Harlow wrote a report about Gage’s case, but he gained little recognition because very few people believed the story to be true. Especially during this time, it just did not seem possible for Gage to be alive. Soon after, Dr. Henry J. Bigelow, a Boston doctor and professor at Harvard Medical College, reached out to Dr. Harlow. Bigelow had asked if Gage would go to Boston so that his case could be presented to the medical school as well as to the Boston Society of Medical Improvement.9 He agreed to do so, and shortly afterwards, Gage donated his tamping iron to the Harvard Medical College for display.10 After some time, Gage traveled to many places in England before stopping at P. T. Barnum’s American Museum in New York City. At Barnum’s Circus, he “displayed himself as a curiosity.” He also worked in livery stables in both Vermont and Chile before eventually developing epilepsy. On May 21, 1861, Phineas Gage “died in status epilepticus,” an intense and prolonged seizure that was almost certainly caused by lasting effects of his brain injury.11

To this day, there are still debates over what exactly initiated the tamping iron’s trajectory. During the process of tamping, sand has to be poured over the powder and fuse after they have already been adjusted. In Dr. Harlow’s account, he claims that Gage became distracted by some of the men in his crew, accidentally dropping his iron before the sand had been poured, directly hitting the rock. This ultimately caused a spark to ignite, leading the tamping iron to shoot upward into Gage’s averted head. However, Dr. Bigelow believed that the powder and fuse had already been adjusted, and Gage was waiting for another worker to pour in the sand. As he was waiting, he then got distracted by nearby member of his crew and turned his head. Moments later, assuming the sand had been poured, Gage dropped his tamping iron on the rock, causing the explosion. Harlow’s account also claims that Gage was sitting on a rock similar to a shelf slightly above the hole when the accident happened. Bigelow’s account, on the other hand, claims that Gage was standing while leaning over the hole when the accident happened. Although there is no way to know which claim is correct, both of them are “consistent with the pattern of injury”.12

Nevertheless, this case study has proven to be of great significance when considering the difficulties of gaining information on the variety of functions served by the frontal lobes of the human brain. Scientists and psychologists have been able to look into both cognitive and behavioral functions involved in the prefrontal region which, prior to Phineas Gage, was nearly impossible.13 Phineas Gage’s incident has enabled a wide expansion of knowledge in science and modern medicine, not only when it comes to behavior and emotion, but the causes of alteration of personality as a whole. Despite just being a railroad construction worker in an incredibly small town, Gage has become one of the most well known people in the study of psychology because of this physically and mentally transformative experience that was laced with a lot of luck.

- Malcolm Macmillan, “Restoring Phineas Gage: A 150th Retrospective,” Journal of the History of the Neurosciences 9, no. 1 (2000): 47. ↵

- Malcolm Macmillan, “Restoring Phineas Gage: A 150th Retrospective,” Journal of the History of the Neurosciences 9, no. 1 (2000): 47. ↵

- Malcolm Macmillan, An Odd Kind of Fame: Stories of Phineas Gage (Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 2000), 23. ↵

- Malcolm Macmillan, An Odd Kind of Fame: Stories of Phineas Gage (Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 2000), 25-26. ↵

- Malcolm Macmillan, “Restoring Phineas Gage: A 150th Retrospective,” Journal of the History of the Neurosciences 9, no. 1 (2000): 47. ↵

- John Fleischman, Phineas Gage: A Gruesome but True Story About Brain Science (New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 2002), 6. ↵

- John Fleischman, Phineas Gage: A Gruesome but True Story About Brain Science (New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 2002), 9-15. ↵

- Encyclopedia of the Human Brain, 2002, s.v. “VI. Stories About Phineas Gage, 1848-2002,” by V.S. Ramachandran. ↵

- John Fleischman, Phineas Gage: A Gruesome but True Story About Brain Science (New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 2002), 19-22. ↵

- John Fleischman, Phineas Gage: A Gruesome but True Story About Brain Science (New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 2002), 42. ↵

- Kieran O’Driscoll and John Paul Leach, “No longer Gage: an iron bar through the head,” US National Library of Medicine 317 (1998), 1. ↵

- Malcolm Macmillan, An Odd Kind of Fame: Stories of Phineas Gage (Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 2000), 27-29. ↵

- The Concise Corsini Encyclopedia of Psychology and Behavioral Science, 2004, s.v. “Phineas Gage,” edited by W. Edward Craighead and Charles B. Nemeroff. ↵

Tags from the story

brain injury

Dr. Henry J. Bigelow

Dr. John Martin Harlow

frontal lobe

Phineas Gage

psychology

railroad

Isabella Torres

My name is Bella Torres and I am from McKinney, Texas. I’m a Psychology major and Communication Studies minor at St. Mary’s University in San Antonio, Texas, graduating class of 2023. I have a passion for volunteering and helping those in need as well as expanding my knowledge in any way that I can.

Author Portfolio Page