November 7, 2021

Seeing Red: The Design of Mao-Era China Propaganda

From before his rule to the end of his dictatorship, Chairman Mao was interested in all aspects of propaganda.1 Many of the articles for the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) on how to create propaganda was written by Chairman Mao himself, as he was deeply involved in the CCP Central Propaganda Department and its management. Such involvement is plainly evident, as Mao was often responsible for writing and publishing articles on how the protocols of propaganda were to be carried out under his rule.2 His direct involvement with the propaganda sector of government administration undoubtedly aided in fully establishing his control of the People’s Republic of China and perfecting his public image. So what were the tactics that Mao’s regime utilize? How did Mao use tradition and culture to sway his citizens? Perhaps the answer lies within the very design of propaganda.

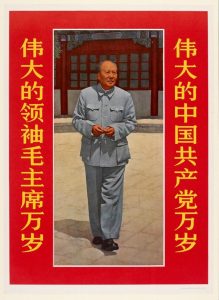

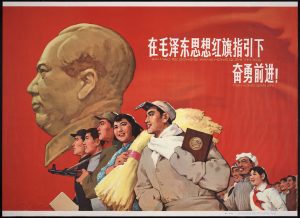

Red–a primary color, attention-grabbing, vibrant, passionate, evoking strong emotion. It is well understood that color has the ability to influence mood–which can be traced back to the evolutionary need to easily identify what is harmful and what is not.3 Color played a large part in Mao-era China, most notably when it came to propaganda poster art. And no color was quite as prevalent in Chinese propaganda as the color red. Whether or not Mao and his subordinates were aware of the inherent emotional influence of color is up to speculation. However, we can at least be certain that Mao did understand the cultural impact of color.

Indeed, the oldest symbol of socialism is the Red Flag, as the color red was meant to represent the blood shed by the working class 4 Is it any wonder why red was chosen as the favored color for propaganda by the CCP–of which the promotion of communist sensibilities obviously held high priority? Nonetheless, red has always held extreme cultural and artistic significance in China. In early China, artisans predominantly utilized red as a dominant color within illustrations and to color pottery, gates, bridges, houses, and palaces. However, the popularity of red is not a coincidence, as red has symbolized good fortune and joy throughout much of Asia’s history.5 Mao understood that Chinese citizens would have an emotional response to red specifically, not just because of humans’ evolutionary response to red, but due to red’s cultural connotations of prosperity.

Red had come to symbolize communism and loyalty to the government. In turn, the color was readily incorporated in almost every example of propaganda posters and art created during the Mao era. Wherever the face of Mao Zedong was depicted, the color red is sure to be found.

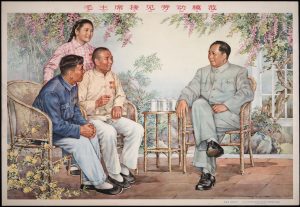

The imagery of “exceptional individuals” is often seen in Mao-era propaganda. From the self-sacrificing “hero” of the revolution, willing to die for the state’s cause, to the “Model Worker,” a family man that represents the ideals of industrialism–these icons were set examples of what every citizen should strive to live up to, the perfect patriot.6 Even today in modern China, patriotism is a deeply held value that is often used in political messaging. Xi Jinping, the General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party and Chairman of the Central Military Commission, and the current President of the People’s Republic of China, explains best why patriotism is such an effective tool:7

“Patriotism has always been the inner force that binds the Chinese nation together, and reform and innovation have always been the inner force that spurs us to keep abreast of the times in the course of reform and opening up.”8

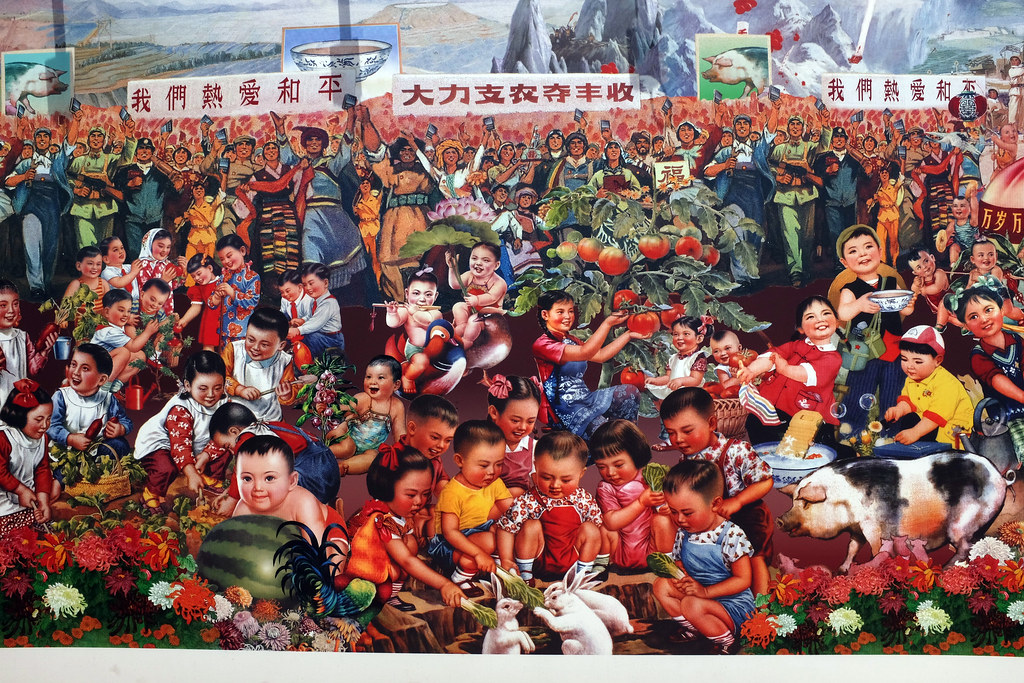

Patriotic icons were not just used to establish social norms, but also they were used to present an idealized version of the revolution and the then-current living conditions within the Peoples Republic of China. Mao-era propaganda centered around themes of unity, feelings of belonging, and above all, nationalism, and to be “other” and to not “belong” was made clear by propaganda rhetoric to be a carnal sin.9

During his rule, Mao widened the scope of propaganda to include the politicization of citizen’s everyday life in increasingly intimate ways. Soon, the influence of propaganda was essentially inescapable as it seeped into every aspect of China’s citizens, in particular, family life. The constant ideological remolding via propaganda became a normalized facet of life in the Peoples Republic of China. Due to the unyielding infiltration of propaganda, through every means of communication, many scholars have speculated that the Chinese citizens eventually internalized the rhetoric distributed by propaganda, though only via what author James Farley calls “message fatigue” and “conformed outwardly but doubted inwardly.”10 However, Farley also points out that many scholars hold the sentiment that the people deeply internalized the propaganda, which is how many Chinese citizens became fiercely loyal to the state, even to their own detriment. Writer Andrew Kuech argues that whatever the public feelings were on the extreme production of propaganda may have been, however uninspired, “was nonetheless effective insofar as it increasingly demanded specific behavioral responses that were inseparable from propaganda itself.” It cannot be stressed enough that the tactics of visual persuasion and controlled media were not the only reason that Mao’s brand of propaganda was successful. Much of its success was in thanks to the sheer relentlessness of political messaging manufactured at extreme rates. Simply put, the propaganda was inescapable, and the consequences of refusing the government-pushed rhetoric were immediate. Many people just became worn down.11

- Anne- Marie Brady, Marketing Dictatorship: Propaganda and Thought Work in Contemporary China (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2008), 35-37. ↵

- Jianguo yilai Mao Zedong wengao (The Writings of Mao Zedong since 1949) (Beijing: Zhongyang wenxian chubanshe, 1987), vol. I, 730. ↵

- Shannon B. Cuykendall and Donald Hoffman, “From Color To Emotion,” pdf, 1-2, http://www.cogsci.uci.edu/~ddhoff/FromColorToEmotion.pdf ↵

- Jan ten Brink, Robespierre and the Red Terror (Lansing: University of Michigan, 1899), 117-118 ↵

- Huang Qiang, 2011. “A Study on the Metaphor of ‘Red’ in Chinese Culture,” American International Journal of Contemporary Research 1 , no. 3 (2011): 99–100. ↵

- Anne- Marie Brady, Marketing Dictatorship: Propaganda and Thought Work in Contemporary China (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2008), 49. ↵

- “Xi Jinping: From Princeling to President,” BBC News, May 12, 2021, sec. China. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-pacific-11551399. ↵

- Xi, The Governance of China, 42. ↵

- Anne-Marie Brady, Marketing Dictatorship: Propaganda and Thought Work in Contemporary China (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2008), 51-53. ↵

- James Farley and Matthew D. Johnson, Redefining Propaganda in Modern China : The Mao Era and Its Legacies (Routledge, 2021), 12. ↵

- James Farley and Matthew D. Johnson, Redefining Propaganda in Modern China : The Mao Era and Its Legacies (Routledge, 2021), 12-13. ↵

Tags from the story

Mao-era propaganda

Recent Comments

Trenton Boudreaux

A very well written and interesting article on one of the most important actions necessary to be a long ruling dictatorship, effective propaganda. If you can get your people to associate you with positive images emotionally, even on just the outside, then you have an effective state. Mao, as the article states, clearly understood this, emphasizing important aspects of Chinese culture and twisting them to benefit his regime.

18/11/2021

9:52 am

Phylisha Liscano

This was a very interesting article and well-written. I enjoyed the images that were provided in the article because they allowed me to get a visual of the topic. Learning that Chairman Mao knew how to get an emotional reaction out of the people with images is very clever. Overall great article and I thoroughly enjoyed getting the chance to read this article.

18/11/2021

9:52 am

Christopher Metta Bexar

I found the article to be well written and interesting. I appreciated that she discussed the history of the color read and why Chairman Mao chose it as his dominant color. It was good that she used more illustrations than might have been required to illustrate her points . The illustrations also helped with her explanation of the psychology of the propaganda, it helped me to see how Chairman Mao attempted to reach out to the Chinese people.

14/11/2021

9:52 am