February 19, 2018

She Sells Seashells by the Seashore: The Story of Mary Anning

Winner of the Spring 2018 StMU History Media Award for

Article with the Best Title

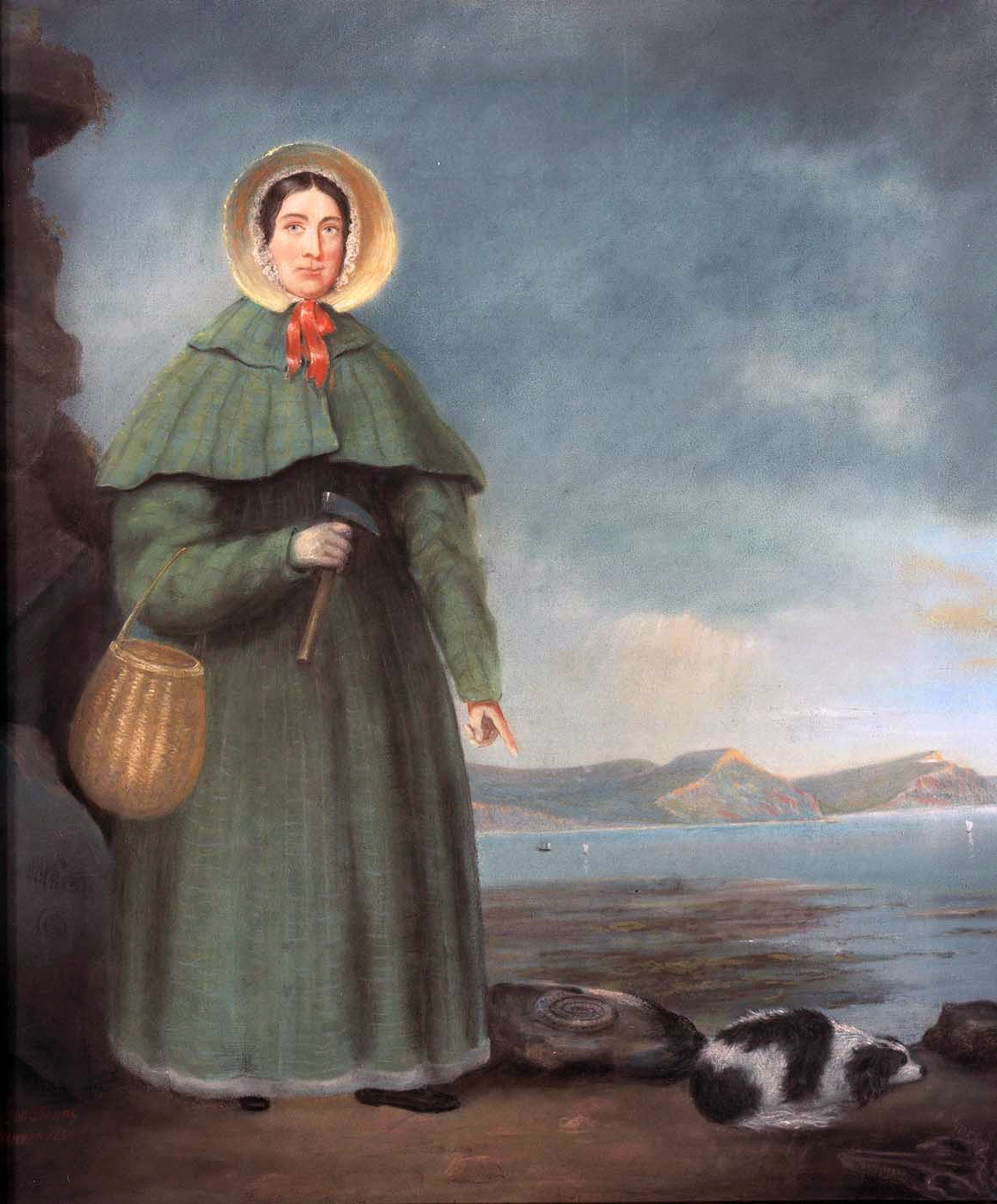

A storm was brewing over the little town of Lyme Regis in Dorset, England, also commonly referred to as the Jurassic Coast. Along the coast we find a young girl, skimming the sea shore and cliffs for a prehistoric treasure. This treasure she was seeking consisted of fossilized bones of an unknown creature, and although fossils were plentiful on this coast, they required significant skill to extract. About 200 million years earlier, the region had been a sea bottom, where numerous dinosaur remains became fossilized after their death. As sea levels fell, these fossils could be found on the beach and above it in the rocky cliffs. The young girl continued to carefully examine the beach and cliff sides, confident in her skills, and even more so, motivated, knowing that the sale of her findings would help her family out of poverty. If someone were to see a young girl partaking in such a strenuous activity, a boy’s activity, what would they say? Having already found the skull of this unknown beast, she strongly believed from her experience fossil hunting on the land that she could unearth the remaining skeleton. The winds began to howl while the rain began pouring down, the way that storms in this region normally did. Over time, such weather exposed large bones that protruded from a nearby cliff side.1 The young girl would revisit this cliff the next day to discover that she had finally found her treasure! The year was 1811, and the girl’s name was Mary Anning. While it has been debated whether Mary’s brother, Joseph, found the skull first or whether he helped Mary in her discovery in general, it is clear that she alone is primarily responsible for finding the well-preserved, remaining pieces to what would be named an Ichthyosaurus (“Fish Lizard”). Though fragments of the Ichthyosaurus had been previously discovered as early as 1699 in Wales, she was the first to find a complete skeleton. Anning hired workers to excavate around the area in which the thirty-foot creature was embedded. Anning sold this skeleton to Henry Hoste, a local collector for £23, and it would be subsequently sent to the London Museum of Natural History. The unearthing of the Ichthyosaurus created a sensation, making Mary Anning somewhat famous.2

Robert Anning, Mary’s father, taught Mary and Joseph to uncover and preserve these fossils or “curiosities,” which were coiled shells that were later determined to be ammonites, a type of mollusk that lived in the Jurassic Period. After Robert passed away in an accident in 1810, a year prior to her famous discovery, she found herself on the shore more frequently, perhaps in order to preserve the memories she shared with him.3 In fact, she did so due to the fact that the Annings had excellent skills in preserving the fossils, and they were able to sell them to tourists who came to admire the mysterious Jurassic Coast. Women in the eighteenth century had little access to education and the goal of women’s education was to attain an ideal “womanhood.” A “proper education” was viewed as one that supported domestic and social activities but disregarded more academic pursuits.4 Mary had little education, and dedicated most of her time to learning the fossil business with her father instead, which resulted in her developing an extraordinary skill. Selling fossils was essentially the only way that Mary kept her family from destitution after her father passed leaving them with a debt of £120.5 Geology required fieldwork, which could be difficult for women to pursue, but it also allowed women to work as scientific illustrators and as amateur fossil collectors who could contribute to the growing body of knowledge on geological features.6 At most, in a paid capacity in paleontology, drawing samples or illustrating books was a favored pastime, as for example, in Sowerby’s Mineral Conchology in 1813.7 It was certainly peculiar for a young woman in that era to get her hands dirty, particularly in a field of work that marginalized women. However, Mary had found her passion and the groundbreaking discovery of the Ichthyosaurus had ignited the coals that would help fuel her drive to her ultimate goal of becoming a respected paleontologist.

Mary Anning continued on her scientific journey in search of unique fossils that could help her and the scientific community learn more of the region’s past. She devoted her time to her shop, her mother, her brother, and to geological science. By this time, Mary had become flawless at the art of paleontology by removing fossils without causing further damage. In fact, Anning’s skills were developing great capacities. She became a great observer who could provide vital information to other scientists who had been attracted to the region after her discoveries. She was so well acquainted with the land and weather that she even began to predict where to find fossils after the storms would take place.8 Mary was a largely self-educated and highly intelligent woman, even teaching herself French so that she could read Georges Cuvier’s work in the original French.9 She became very popular and even earned a few nicknames, like “The Princess of Paleontology,” “the Mother of Paleontology,” “the Dinosaur Woman,” and “the Fossil Woman.” Unfortunately, some of the same scientists who studied with Mary and accompanied her on her expeditions, took credit for her discoveries by publishing books based on her findings.10 It is a mystery as to why Mary never published any of her own findings. Still, Mary pressed on with her passion for paleontology in high gear.

Finally, in 1830, Anning discovered another prehistoric marine creature, only this time, it was one that had never been seen before. The nine-foot Plesiosaur (“near lizard”) had a long neck, small head, and fat body, and appeared to resemble a lizard more than a fish, with appendages that were very similar to a human hand. This was arguably Anning’s greatest find for many reasons. This discovery presented clear evidence that prehistoric animals looked very different from modern animals and being that Anning’s discovery was so rare, it led to the creation of a new genus. Prior to this, in 1828, Anning had discovered the first evidence of a prehistoric winged creature, the Pterodactylus Macronyx, meaning “winged fingers.” In this same year, she also unearthed the anterior sheath and ink bag of Belemnosepia. A year later, Anning discovered more unusual skeletal remains of creatures that were thought to be of animals, yet discovered in different parts of the world, like the Squaloraja (a fish-like creature). The Squaloraja fish seemed to be an evolutionary step between rays and sharks. This was yet another reason Anning’s findings were found to be controversial. From the information gleaned from her fossils, such as the types of rocks surrounding the remains, it was clear that many species had lived in previous geological eras. Her findings seemed to contradict the teachings of the Anglican Church that God created all creatures in the six days of creation. Mary’s work provided evidence that the skeletons she found had died long before humans first appeared, but the Church’s official position was that Anning’s findings could not be correct.11

While Mary Anning did indeed earn herself some notoriety, the true test was never in fame, or even fortune, but from respect and acknowledgment from those in her field. Mary became successful in her business of selling fossils; in fact, she sold the Plesiosaurus Macrocephalus to a collector by the name of William Willoughby for £200. This wouldn’t be enough though. In 1838, Anning’s shop was supplemented by a government grant that was paid for by the British Association for the Advancement of Science. Mary lived her life completely dedicated to paleontology, never marrying nor having children.12 This could have added extra controversy as she was a woman in science, and society would have marginalized her even more if she had had a family, expecting that she should remain at home and take care of her family.13 That may even be a reason as to why she avoided the latter. In addition, Anning’s hometown of Lyme Regis relied heavily on Mary and her shop as a tourist attraction. When she passed away of breast cancer, Lyme Regis suffered financially, but most importantly they mourned their beloved star. The town placed a stain glass window in the church of Mary Anning collecting fossils, and commemorated her by adding a plaque near the cliff where she discovered the Ichtyosaurus.14

While the primary goal was for Anning to become a member of the Geological Society, she was never allowed to present her work because she was a woman and failed to admit her during her lifetime. However, The Geological Society did provide her with funds when she fell ill with cancer, and issued an honorary membership to Anning when she passed away in 1847, because at this time men were still the only ones allowed to be full members. It wouldn’t be until the end of the nineteenth century that women in Europe would have the opportunity to become professionally educated and, therefore, become professional geologists and paleontologists. Today, scientists recognize Anning as an authority on British dinosaur anatomy. It is even rumored that the tongue twister “She sells seashells by the Seashore” was written about Mary and her love for paleontology. It is because of Mary Anning and other women of the nineteenth century that did important scientific work, sometimes under difficult conditions, most times with little recognition, that paved the way for women of the twentieth century to enter the sciences in greater numbers. Unfortunately, women are still underrepresented in the geological world at the higher levels of expertise, but perhaps as we move through the twenty-first century, the role models from previous eras will act as a source of encouragement for women to participate in sustaining our geological heritage.15

- Encyclopedia of World Biography, 2004, s.v. “Mary Anning,” by Alex K. Rich. ↵

- Encyclopedia of World Biography, 2004, s.v. “Mary Anning,” by Alex K. Rich. ↵

- Encyclopedia of World Biography, 2004, s.v. “Mary Anning,” by Alex K. Rich. ↵

- Feminism in Literature: A Gale Critical Companion, 2005, s.v. “Women in the 16th,17th, and 18th Centuries: Introduction,” by Jessica Bomarito and Jeffery W. Hunter. ↵

- Encyclopedia of World Biography, 2004, s.v. “Mary Anning,” by Alex K. Rich. ↵

- Science and Its Times, 2000, s.v. “Women Scientists in the Nineteenth-Century Physical Sciences,” by Mary Hrovat. ↵

- World of Earth Science, Vol. 1, 2003, s.v. “History of Geoscience: Women in the History of Geoscience.” ↵

- Encyclopedia of World Biography, 2004, s.v. “Mary Anning,” by Alex K. Rich. ↵

- The World of Earth Science, 2003, s.v. “Anning, Mary (1799-1847).” ↵

- Encyclopedia of World Biography, 2004, s.v. “Mary Anning,” by Alex K. Rich. ↵

- Encyclopedia of World Biography, 2004, s.v. “Mary Anning,” by Alex K. Rich. ↵

- Encyclopedia of World Biography, 2004, s.v. “Mary Anning,” by Alex K. Rich. ↵

- Feminism in Literature: A Gale Critical Companion, 2005, s.v. “Women in the 16th,17th, and 18th Centuries: Introduction.” ↵

- Encyclopedia of World Biography, 2004, s.v. “Mary Anning,” by Alex K. Rich. ↵

- World of Earth Science, Vol. 1, 2003, s.v. “History of Geoscience: Women in the History of Geoscience.” ↵

Tags from the story

Mary Anning

paleontology