December 5, 2018

Stanford Prison Experiment: 6 Days That Shocked the World

On August 14, 1971, in the basement of the Psychology department building at Stanford University, one of the most controversial and well-known psychological experiments took place. The experiment was originally designed to last a full two weeks, but due to cruel circumstances, the experiment would last just six days. Little did the researchers know that those measly one-hundred and forty-four hours would not only change the lives of the twenty-four male college students that they studied, but also that of themselves. The ultimate goal of this short trial? To figure out if personality traits are responsible for the abusive behavior that takes place in the prison environment.1

Philip Zimbardo, the head researcher of the world-famous experiment, graduated summa cum laude in 1954 from Brooklyn College, where he triple majored in psychology, sociology, and anthropology. He later went on to receive his masters and Ph.D. in psychology from Yale University. Zimbardo found something appealing about the college environment, however, and began teaching right after graduation. He became a psychology professor at many different well-known institutions, including Yale, New York University, Colombia, and Stanford University. It is no stretch of the imagination that someone like Zimbardo would be the one to undertake this experiment. While teaching at Stanford University, Zimbardo was contacted by the U.S. Office of Naval Research. The organization asked the psychology professor to head a federally-funded social experiment, one that would recreate and study a specific prison environment. Zimbardo knew that this experiment would have interesting results, and he could not resist the offer. Although Zimbardo did not know it then, the prison experiment would nevertheless become the greatest accomplishment of his career.2

The main aspect of the experiment would be the people inside the Stanford “Prison.” Zimbardo and his team were tasked with the most difficult part of the process for making this experiment become a reality. He and his team would have to find college-aged men who were both willing and physically and mentally healthy. Zimbardo and his team decided that the best way to reach these college men was through an advertisement in the newspaper. The ad was straightforward in its construction, reading “Male college students needed for psychology study of prison life. $15 per day for 1-2 weeks beginning Aug. 14. For further information & applications, come to room 248. Jordan Hall, Stanford U.”3 Originally, the team received over seventy immediate applicants, but after they ran background checks on the individuals, only twenty-four men remained. The next step in the experiment was to assign the twenty-four test subjects to the roles of either prisoner or guard. Oddly enough, there was no elaborate test to determine just who had the luxury of becoming a guard or who was destined to become a prisoner. Instead, the team simply made the test subjects flip a coin.

After the roles had been assigned, the team was tasked with constructing the entirety of the mock prison. After some discussion, the team decided that the “prison” was built within the basement of the psychology building at Stanford University. Over the course of a week, the makeshift prison quickly took shape. Bars were placed over the doors, and the team even converted the storage closet into a “solitary confinement center.” The team’s goal was simple: make the environment as close to an actual prison as possible, so that the test subjects would feel as though they were actually imprisoned, so as to produce accurate results. After consulting with ex-prisoners, the research team had made the perfect mock prison, and everything was in place for the experiment. The volunteers were picked, the prison was designed, and the only thing left to do was to begin the Stanford Prison Experiment.4

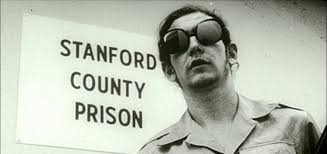

It was early Tuesday morning when nine separate young men each heard a loud banging on their front doors. The individuals were forced to stop whatever activity they were in the middle of to walk to the door, likely wondering who could need them at such an early hour. To their surprise, they opened their doors to officers of the Palo Alto Police force, and were handcuffed on the spot. Each of the men were unaware that this was part of the newspaper ad they responded to just a few weeks prior. This was just one of the many events that the twenty-four volunteers became aware of during the experiment. They were destined to be shoved into a police car in front of their families and neighbors, and ride to the “prison” awaiting them in the basement. Upon their arrival, each individual was processed as if they were at an actual prison. Zimbardo and his team used different mental tactics to humiliate each of the new inmates. Each participant was stripped of their clothes, forced to wear a “dress” with no underwear, a stocking cap, and a chain around their ankles at all times. After their brief and confusing initiation, all of the prisoners were given an ID number. This number, for the duration of the experiment, grew to replace their whole identity. The individuals that were chosen to be guards were treated much differently, and they worked eight-hour shifts. Additionally, they were allowed to leave the prison, unlike the inmates. Each guard was given a police uniform as well, consisting of sunglasses, khakis, batons, and whistles.5

Inside Higher Ed

The first day of the experiment was largely uneventful. The prison and the test subjects within it were simply awkward. The guards said very little, opting instead to just look at each other. On the other side of the bars, the prisoners did the same. It was obvious to the researchers that no one had yet assumed their role. Zimbardo and his team watched on with growing disappointment, and couldn’t help but wonder if their experiment was going to fail.

Everything changed on the second day. The prisoners were tired of the constant nagging by the guards, and they had quickly decided to do something about it. The prisoners gathered together and decided to put together a rebellion. The researchers could only watch in awe as the prisoners began to organize and plan their escape. From this point on, the entire experiment changed. When the time came for action, a group of prisoners rushed the guards. Although the guards were surprised by the sudden outburst, they had reacted quickly and effectively, resorting to physical violence to repress the aggressors. From this point forward, everyone forgot that they were, in fact, simply locked in the basement of the Stanford Psychology building. As far as the prisoners had been concerned, they were in an actual prison. At the end of the scuffle, the guards forced the main leader of the riot into the storage closet-turned-solitary confinement center. In order to maintain control of their “prison,” the guards used psychological tactics to undermine the independence of the prisoners. The guards put the good prisoners in a different cell and allow them to sleep, wear their clothes, and eat better food than the rest. The other prisoners were stripped naked, their beds taken away, and forced to eat poor food. The guards had found success in this tactic, and it caused the prisoners to comply with any order they were given. Soon, the prisoners had lost all hope of leaving the prison.

The guards continued to use inhumane tactics to undermine the prisoners in order to maintain control over them. The inmates were constantly deprived of sleep and were woken up in the middle of the night to recite their number count. At one point, the prisoners were forced to use plastic buckets as toilets. It did not take long before the situation got out of control. After the experiment, Zimbardo admitted that “The experiment was the right thing to do, [but] the wrong thing was to let it go past the second day.”6

The breakdown of the prisoners persisted for the following four days. The torment of the test subjects eventually became so bad that twenty-two year old inmate Douglas Korpi was struck by a severe mental breakdown, and had to be released from the rest of the experiment. He began kicking on one of the cell doors screaming at the top of his lungs, “I mean, Jesus Christ, I’m burning up inside! Don’t you know? I want to get out! This is all fucked up inside! I can’t stand another night! I just can’t take it anymore!”7 Another inmate, Richard Yacco, was released a day early because he was showing signs of severe depression. Before his release, Yacco recalls being told, “You can’t quit — you agreed to be here for the full experiment.”8 Another mock prisoner stated in an interview that “I began to feel that I was losing my identity, that the person that I called Clay, the person who volunteered to go into this prison…was distant from me, was remote, until, finally, I wasn’t that. I was 416, I was really my number. And 416 was gonna have to decide what to do.”9

The purpose behind the entire experiment was to test the theory that personality traits are responsible for abusive behavior that happens inside of prisons. The results? When put in a powerful position, people will always have a tendency to behave in ways that are different than their actions on a regular basis, and when put in a situation where people have absolutely no control in their situation, they become depressed and passive.

After this experiment took place, laws were implemented to make sure another social experiment like this were to never again take place on American soil. However, after finally hearing about the eventful six days that occurred in the basement of the Stanford Psychology Building in 1971, many people are left skeptical. Some believe that Zimbardo knew exactly what was going to happen and that the experiment itself is fraudulent. In multiple different interviews, both guards and prisoners were quick to state that they were “playing a part they believed they needed to fulfill.”10 Another critical flaw of the experiment is the fact that it is no longer reproducible.

Whether or not you believe that the Stanford Prison Experiment is an act of true science or not, there is no denying the immorality of the events that took place during those six days in the basement of the Stanford Psychology Building in 1971. The twenty-four volunteers and the several researchers that participated in this event are the only ones who truly know whether or not the actions and reactions in that mock prison were genuine or not. Regardless of the truth, the fact remains, that this psychological experiment will forever remain one of the most controversial and well-known experiments to have ever taken place.

- Thomas Blass, Obedience to Authority: Current Perspectives on the Milgram Paradigm (Mahwah, NJ, US: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers, 2000), 35-38. ↵

- Philip G Zimbardo, “Shocking ‘prison’ Study 40 Years Later: What Happened at Stanford?” CBS NEWS (2018): https://www.cbsnews.com/pictures/shocking-prison-study-40-years-later-what-happened-at-stanford/. ↵

- Saul McLeod, “Stanford Prison Experiment,” SimplyPsychology (2017): https://www.simplypsychology.org/zimbardo.html. ↵

- Martin Shuttleworth, “Stanford Prison Experiment,” Explorable, (2018), https://explorable.com/stanford-prison-experiment. ↵

- Maria Konnikova, “The Real Lesson of the Stanford Prison Experiment,” The New Yorker, (2015): https://www.newyorker.com/science/maria-konnikova/the-real-lesson-of-the-stanford-prison-experiment. ↵

- Alastair Leithead, “Stanford Prison Experiment Continues to Shock,” BBC NEWS, (2011): https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-us-canada-14564182. ↵

- Brian Resnick, “The Stanford Prison Experiment is Based on Lies” Vox, (2018), https://www.vox.com/science-and-health/2018/6/14/17464516/stanford-prison-experiment-audio/. ↵

- Romesh Ratnesar, “A Look Back at the Stanford Prison Experiment,” Stanford Magazine. (2011), https://medium.com/stanford-magazine/a-look-back-at-the-stanford-prison-experiment-23c8bb65e37e. ↵

- Maria Popova, “The Stanford Prison Experiment: History’s Most Controversial Psychology Study Turns 40,” Brain Pickings, (2011), https://www.brainpickings.org/2011/08/17/stanford-prison-experiment-40/. ↵

- Greg Toppo, “Time to Dismiss the Stanford Prison Experiment?” Inside Higher Ed, (2018), https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2018/06/20/new-stanford-prison-experiment-revelations-question-findings. ↵

Tags from the story

Philip Zimbardo

Stanford Prison Experiment