April 10, 2022

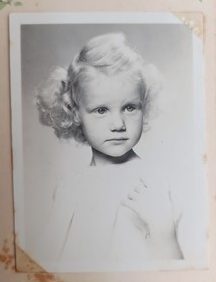

Surviving Internment in Crystal City: the Experiences of Internee Ilse Fischer, a Peruvian-German Child

Stories are told and passed from generation to generation; these stories are spoken and transcribed for future generations to learn about their ancestry. Some stories are true; others may be false. Some stories motivate us on a dark day, some sadden us in solitude, and some enrage us into feeling a sense of injustice. Real-life stories nourish a life lesson. World War II happened between 1939 and 1945. A series of events occurred between the European, Asian, and North American countries. There were more events than simply the political and economic storylines contained in History textbooks. Crystal City Internment Camp, located in Texas, was an Internment Camp with German, Italian, and Japanese families taken from different Latin American countries, one of those countries being Peru. A total of thirteen German-Peruvian families were taken to this camp. One of those families was the Fischer family. The Fischer family lived in this Internment Camp until the end of the war, and in 1946 they were allowed return to Lima, Peru. Ilse Fischer was just two years old when she was taken from Peru with her family to Cristal City, Texas. An Internment Camp was waiting for her. She had no idea what would happen to them; they all just had the hope that they would return home one day. During her time in Crystal City, Ilse wondered whether she would ever be able to go back to her Motherland. This article is about her story. Her story is important for history, and it is worth hearing because it is a story that has never been told. The life of German Peruvians has not been researched as much as Japanese Peruvians during the Internment Camps.

In 1937, Ilse’s father, Walter Fischer, arrived in Lima, Peru, with the mission to find quality cotton for the company he worked for back in Germany. The company needed good quality cotton, and it was Fischer’s mission to find it. At first, he went by himself to Peru; he left his wife, Thea Fischer, and his newborn son, Juergen, in Germany while he determined whether living permanently in Peru was possible. After a year, Fischer decided to bring his family to Lima, and in 1942, Ilse was born in Peru. They lived in a healthy and happy environment; Ilse described that her parents lived happily in Lima in a small house in Miraflores, Benavides Av.1 Little did they know what was about to happen.

In 1936, the U.S. president, Franklin D. Roosevelt, authorized the F.B.I. to start an investigation of citizens and legal residents of German ethnicity, since he was concerned about the growing militancy taking place in Germany. In 1940, Roosevelt created the Secret Intelligent Series to do the same kind of investigations in Latin American countries, which began in May of that year.2 In 1939, the United States initiated a new policy between the U.S. and Latin American countries called the Good Neighbor Policy. Its function was to strengthen relations with Latin American countries. After the beginning of World War II, the policy was used to influence Latin American countries economically and politically, as the United States saw a threat from German businesses growing in the hemisphere.3 The United States intended to eliminate the existing rivalry between the German companies and the national companies in Latin America as they were economically succeeding in countries like Peru as farmers and businesspeople. According to Edward N. Barnhart in his article “Japanese Internees from Peru,” the Japanese community in Peru was also seen as a competition because of their economic success as farmers and businessmen; for that reason, further immigration of Japanese was stopped in 1936. Alberto Ullo, Foreign Minister of Peru, thought this situation had created competition between Peruvian and Japanese businesses, causing social discontent. The current president of the time, Manuel Prado Ugarteche, aroused a kind of social hostility towards the Japanese. The idea of eradicating Japanese competition started to grow in the political branch.4 Both communities were in danger, and that was just the beginning of the Latin American Internment Program.

It was a typical day in the gray city of Lima in 1944 when Walter Fischer was taken from his family by the State Police, as they were looking for all the Germans in the country to intern them in the United States. The rumor of German families being extracted as enemies grew and resounded in the houses of the German communities in Lima.5 For that reason, Mr. Fischer had a bag with clothes prepared next to the door. That day finally came sooner than later, as Ilse’s father was working when the Police found him.6 He was not the only one; hundreds of individuals of German ethnicity were taken from their families. Companies run by Germans and schools for those of German heritage were closed. Thea Fischer was left alone with two children, no money, and without a husband who could protect them or bring food home. How would they survive? Without explanation, the Peruvian authorities took a husband and father away, and weeks passed until they received an answer about Mr. Fischer’s whereabouts.

On December 7, 1941, the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor happened; it was the perfect justification to act and create the Latin American Internment Program. President Roosevelt responded by writing the Presidential Proclamation 2526 a day after the event, December 8, 1941. This proclamation set in motion regulations to enable authorities from all across the United States to detain potentially enemy aliens, of German ancestry who were “not naturalized.”7 Two other proclamations were formed the same day with the same restrictive rules for those of Japanese and Italian ethnicity.8

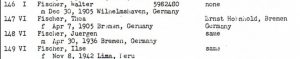

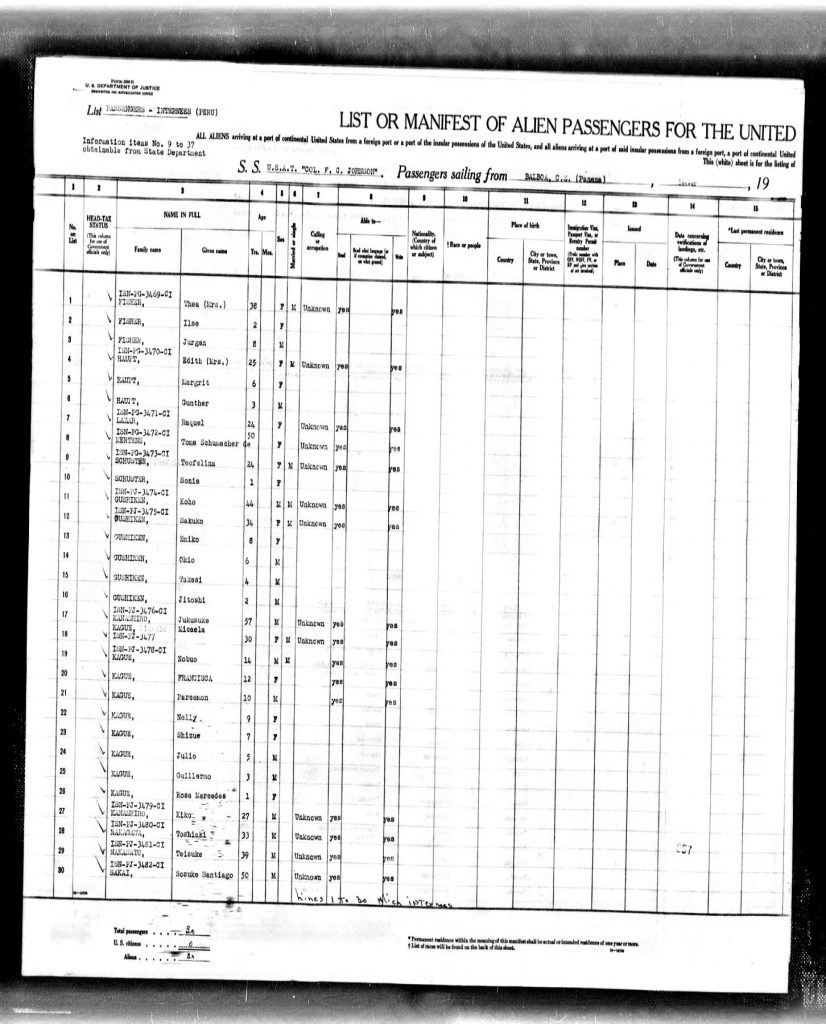

The year Ilse was born, the Rio de Janeiro conference took place. On January 15, 1942, a meeting was requested by the U.S. government. During the Rio Conference, the U.S. insisted on creating an advisory committee for political defense, as German, Japanese and Italian aliens were considered “a dangerous threat” in Latin America.9 Consequently, the pressure from the North American country began, and soon Latin American countries accepted the creation of this committee. As countries began participating in the process of Internment during that period of emergency, the United States agreed to pay for the transportation and detention of these internees.10 Peru had the highest number of Japanese and Germans sent to U.S. internment camps, with 702 from German communities and 1799 from Japanese communities, including women and children.11 Surprisingly, there is little information about the life of German Peruvians during this moment in history. The internment of German Peruvians commenced in 1944. Peruvian authorities called “Policias del Estado” went from house to house and arrested German individuals without giving them a reason why where they were arrested. The rumor of the detentions was known.

Two months after the arrest of Walter Fischer, a letter from the U.S. government addressing the status of Walter Fischer appeared.12 He was interned in the U.S. in a camp only for men of the German community. The letter also offered to take the family to an internment camp in Crystal City, Texas, where they could be reunited with Walter Fischer. Ilse’s mother accepted without hesitation. According to Juergen Fischer, Ilse’s brother, a military truck with other German families led by American authorities, came to the house to take them to the Port of Callao, located on the north side of Lima, Peru.

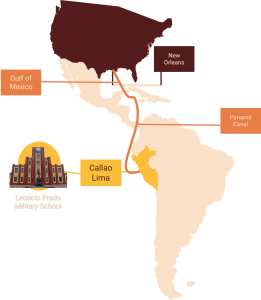

After they boarded a ship in the Port of Callao, they traveled through the Panama Canal, then into the Gulf of Mexico, and finally arrived at the Port of New Orleans. After that, they were taken by train to Crystal City Internment Camp.13 Ilse Fischer remembered these moments in her life as “happy moments.” The camp had all the accommodations of education, food, and living places. Ilse also recalls how there was a school for the kids and a church for all religions. Her father was able to work, as well as other men in the camp.14 As her father was a merchant, he was given a small food market by the authorities in the camp. They were there from 1944 to 1946. She recalls that they were treated well. It was like a bit of a city, where they could study and have fun.15 Throughout their confinement, they lived happily, but behind walls that separated them from freedom; it was not until a year after the war ended that they could see life outside the camp.

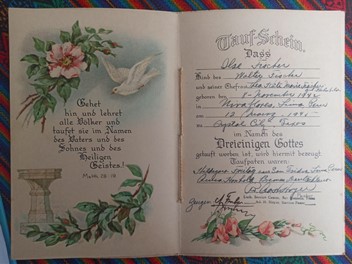

In her book “Daily Life at Crystal City Internment Camp,” Caitlin Dietze explains that the internment camp’s purpose was to unite families from German, Italian, and Japanese communities and preserve the family structure. The camp had recreation spaces and food, water, and energy for the families. Also, international organizations like the Red Cross came to the camp to verify that communities had favorable conditions. Representatives from German and Japanese communities played the role of spokesman; their names were Erich Kirshling and Teikichi Hamaguchi, respectively. Both reported claims or suggestions about the living conditions or asked questions about the internment.16 Children received education and facilities, like a hospital, and a church where children could get baptized and couples could get married; there was even a pool. There were five babies of Peruvian ethnicity born in the camp, and only four citizens of Peruvian ethnicity died in the camp due to health complications.17

In 1946, families in the camp had three options. They could be repatriated to Germany; many Germans had been repatriated to Germany from other camps during World War II. Or, they could return to their Latin American country if they had a family member with that country’s citizenship. Or, if they could not afford the trip or didn’t want to be repatriated to Germany, they would have to stay indefinitely in the Cristal City Internment Camp.18 Returning to Germany was impossible for the Fischers; they talked to their relatives in Bremen, Germany, who advised them not to come to Germany. After the war, Germany was experiencing profound political, economic, and social crises. Luckily, the Fischer family had the money to return to Lima, and in 1946, they returned to Lima, Peru.

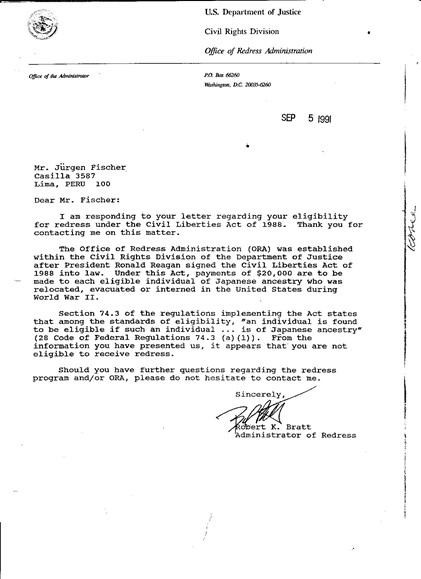

After an arduous trip, the whole family arrived in Lima, and they moved into a new house in San Antonio, Miraflores. They received some of the valuable things they had given to family friends before going to the camp. In time, Ilse’s father started a business, and both children started studying at Pestalozzi School. Ilse remembers that they lived in boxes when they arrived: “Puros cajones, cajones eran nuestras sillas, cajones eran nuestras camas con un colchon encima. Lo más primitivo que uno se puede imaginar.” As they grew up, the topic of their internment was a constant conversation, as the event was one that they would never forget. When Juergen Fischer grew up, he noticed that the Japanese Americans and Latin American internees of Japanese descent received economic compensation, so he decided to send a letter to the U.S Department of Justice regarding their eligibility for the Civil Liberties Act of 1988.19 Unfortunately, they did not receive any compensation due to not being of Japanese ethnicity.

Ilse is the third generation of her family. Her parents and husband had already died. Her brother Juergen lives with his wife in Germany, and she now lives with her youngest son while working in their family pecan company. Ilse Fischer still has questions about her past; she states that when she was a child, she never asked questions, but now with her parents resting in peace, she has many questions with no answers. Now she emotionally lives her history.

She remembers her baptism in the camp, and her brother’s school presentations in the camp’s school. Years later, Ilse decided to return to Texas, this time with her family. She brought her baptism booklet, and returned to the camp: “I am going to take my Baptism certificate, and we are going to go to the Municipality of Texas and they will show us where the camp is.”20 She was interested in knowing more about where it all happened and how it became part of her history: “I thought that all that area was still there.”21 Unfortunately, she did not receive the answer she was hoping for when she arrived. They told her that in the camp, there were never any German internees: “No, there was never a German camp here, Japanese yes but Germans no. And I told him, of course, there was, I had been there myself.” 22 At that moment, she took out the baptism booklet that they had given her in the camp, and she was surprised: “She kept insisting and insisting that there was not, so I took out my… my baptism card with all the stamps and everything from Crystal City Camp and everything and her jaw dropped.”23

These are her memories, memories she will never forget, after years of uncertainty, a blank space in her life rather than a new chapter. Her story is a moment in history to remember and record; it shows a family and country’s culture and history. With her story, I hope we will not forget her; make her life a new part of history, teach it, and make it an example of a past that must not be repeated.

- Ilse Fischer, “Entrevista a Ilse Fischer, interview by Brissa Campos Toscano,” February 26, 2022. ↵

- Leslie B. Rout, Jr. and John F. Bratzel, The Shadow War: German Espionage and United States Counterespionage in Latin America during World War II (University Publications of America, Inc., Maryland, 1986), 28. ↵

- Molina Londoño, Luis Fernando, «Expolios, Deportaciones E Internamientos: El Destino De Los Alemanes Residentes En Latinoamérica Durante La Segunda Guerra Mundial» OXÍMORA Revista Internacional De Ética Y Política, n.º 11 (noviembre 2017): 11. https://doi.org/10.1344/oxi.2017.i11.19940. ↵

- Edward N. Barnhart, “Japanese Internees from Peru,” Pacific Historical Review 31, no. 2 (1962): 169. ↵

- Juergen Fischer and Hannelore Bremen, Entrevista a Juergen Fischer y Hannelore Bremen de Fischer, interview by Brissa Campos Toscano, November 17, 2020. ↵

- Ilse Fischer, Entrevista a Ilse Fischer, interview by Brissa Campos Toscano, Presencial, October 25, 2020. ↵

- “World War II Enemy Alien Control Program Overview,” National Archives and Records Administration, January 7, 2021. https://www.archives.gov/research/immigration/enemy-aliens/ww2. ↵

- Congress.gov. “Congressional Record Extensions of Remarks Articles.” April 7, 2022. https://www.congress.gov/congressional-record/1999/11/19/extensions-of-remarks-section/article/E2525-3. ↵

- Randall B. Woods, “Decision-Making in Diplomacy: The Rio Conference of 1942,” Social Science Quarterly 55, no. 4 (1975): 901–18, https://www.jstor.org/stable/42859419. ↵

- Natsu Taylor Saito, “Justice Held Hostage: U.S. Disregard for International Law in the World War II Internment of Japanese Peruvians–A Case Study Symposium: The Long Shadow of Korematsu,” Boston College Law Review 40, no. 1 (1998): 282 ↵

- “White to Lafoon Memo, 30 Jan 1946,” German American Internee Coalition (website), February 24, 2016. https://gaic.info/white-to-lafoon-memo-30-jan-1946/. ↵

- Juergen Fischer and Hannelore Bremen, Entrevista a Juergen Fischer y Hannelore Bremen de Fischer, interview by Brissa Campos Toscano, November 17, 2020. ↵

- Juergen Fischer and Hannelore Bremen, Entrevista a Juergen Fischer y Hannelore Bremen de Fischer, interview by Brissa Campos Toscano, November 17, 2020. ↵

- Ilse Fischer, Entrevista a Ilse Fischer, interview by Brissa Campos Toscano, February 26, 2022. ↵

- Ilse Fischer, Entrevista a Ilse Fischer, interview by Brissa Campos Toscano, Presencial, October 25, 2020. ↵

- Caitlin T. Dietze, Daily Life at Crystal City Internment Camp 1942-1945 (University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations, 2016), https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td/2137. ↵

- Werner, Ulrich R. “Crystal City Camp Layout.” 2018. Map. The Freedom of Information Times. https://www.foitimes.com/CampHousing.pdf. ↵

- Ilse Fischer, Entrevista a Ilse Fischer, interview by Brissa Campos Toscano, February 26, 2022. ↵

- Juergen Fischer and Hannelore Bremen, Entrevista a Juergen Fischer y Hannelore Bremen de Fischer, interview by Brissa Campos Toscano, November 17, 2020. ↵

- “Yo voy a llevar mi partida de Bautizo, y vamos a ir a la Municipalidad de Texas y que nos enseñen donde esta el campamento.” ↵

- “Yo pensaba que toda esa area seguia ahi.” ↵

- “No, aca nunca hubo un campamento de alemanes, de japoneses si pero de alemanes no. Y yo le dije claro que si, yo misma eh estado ahi.” ↵

- “Me insistía y me insistía que no, entonces yo saque mi…mi tarjeta esta de bautizo con todos los sellos y todo del campamento Crystal City y todo y se quedó boquiabierta.” ↵

Tags from the story

Crystal City Internment Camp

Ilse Fischer

Peruvian-German internees

Brissa Campos Toscano

I was born and raised in Lima, Peru. I am an International and Global Studies major with a Political Science, History, and Music minor at St. Mary’s University in San Antonio, Texas, Class of 2024. I am interested in Latin American Politics as well as its history and ethnic background. I hope one day to work in my country’s government or in the United Nations. With that position, I wish to help people in need and impact people’s lives with my work.

Author Portfolio PageRecent Comments

Andrew Ponce

The author interestingly provides the reader with a different perspective to view WWll in; shifting the focus of political and economical impact, to the much more relatable family related impact that occurred during this time. Every body knows the impact the war had on Europeans and Americans from the U.S, however not many people know or hear of the impact the war had on Latin American countries and their people. This article informs the reader of the less popular experiences of a Peruvian during a time of global war and finds a way to engage the reader through the articles syntax and descriptive images. Great article!

12/04/2022

2:40 pm

Ariana Aguilar

Thank you so much Brissa for taking your time and do your research about this important topic in history that a lot of people didn’t know about. I found your article extremely interesting and useful. I am taking a history class in which I am learning about these internment camps and I think your publication will help me more understanding how people in these camps lived.

10/04/2022

2:40 pm