April 7, 2021

The Canadian Caper – The Most Audacious Rescue in History

The day was November 4th, 1979. The Iranian revolution against the Shah was in full swing, and Islamic students had just formed a violent mob and stormed the wall surrounding the compound, breaking into the American Embassy building in Tehran, Iran. They took the diplomats and embassy workers hostage, using them as bargaining chips as they demanded extradition of the Iranian Shah, who had been admitted to the United States for cancer treatment. While most of the Americans who had escaped the initial attack or who had not been at work were quickly rounded up and captured, six Americans had managed to make it to the streets and scatter, finding temporary shelter wherever they could as they sought to escape the Muslim mob. After trying and failing to make it to the British Embassy, the diplomats were forced to face the facts—they were stranded in Tehran with no way out.

The six embassy members spent the next few days hiding in fear, with five of them huddled in the apartment owned by Robert ‘Bob’ Anders, a member of the group, before moving from house to house, afraid to stay in one place for very long. The sixth American, Lee Schatz, had managed to make it to the Swedish Embassy, who took him in and hid him. After several days of being on the run, Robert Anders decided to make contact with a friend of his in the Canadian Embassy, John Sheardown, who took his message to the Canadian Ambassador, Ken Taylor. Taylor, to his credit, instantly agreed to shelter the fugitives. “Why didn’t you call sooner?” he asked. “Of course we can take you in. Count on us.”1 Sheardown and Taylor each took multiple Americans into their own homes, splitting up the group to minimize the risk of detection. Later, Lee Shatz would join his compatriots, with the Swedes and the Canadians agreeing that he could more easily pass as a Canadian should an inspection be conducted. However, the longer this state of affairs dragged on, the riskier it became for all involved. The remainder of the Shah’s government had fled, and the revolutionaries, led by their new ruler, Ayatollah Khomeini, were extremely hostile to the United States, with the situation growing more violent by the day. The workers at the American Embassy, as they had started to be besieged by the Islamic mob, had destroyed and hid as much of the equipment and sensitive documents as they could, including, most importantly, any records of personnel, but it was public knowledge that the Iranians were trying to reconstruct what they could to double check their list of hostages. The militants had assembled teams to try and put back together the shredded and destroyed documents (which were eventually successfully pieced together and published by Iran, under the title Documents from the US Espionage Den).2 With the pressure and tension mounting, and knowledge of the hidden Americans starting to leak, both Canada and the United States agreed something had to be done to evacuate them, and fast.

The task of coming up with a rescue operation was eventually assigned to a CIA agent by the name of Tony Mendez. The difficulties and risks of this operation were obvious, Mendez noted.

“The complexities were evident. We needed to find a way to rescue six Americans with no intelligence background, and we would have to coordinate a sensitive plan of action with another US Government department and with senior policymakers in the US and Canadian administrations. The stakes were high. A failed exfiltration operation would receive immediate worldwide attention and would seriously embarrass the US, its President, and the CIA. It would probably make life even more difficult for all American hostages in Iran. The Canadians also had a lot to lose; the safety of their people in Iran and security of their Embassy there would be at risk.”3

The rescue operation needed a cover story for entering Iran. Given that it was winter and in the middle of a revolution, however, there weren’t many options that would stand up to any kind of scrutiny from the Iranians. The decision was ultimately made to go with the disguise of a film crew getting footage for a movie. Who else but filmmakers, the CIA’s planners figured, would go to Iran in the midst of a revolution?4 As one of the escapees put it, “We had the [choice of] going out as nutritionists, something we knew nothing about; oil company people, even less; or going out with this movie production company, which had all the props, concrete things that made it believable – business cards, the magazine with an advertisement for our movie site search [etc].”5

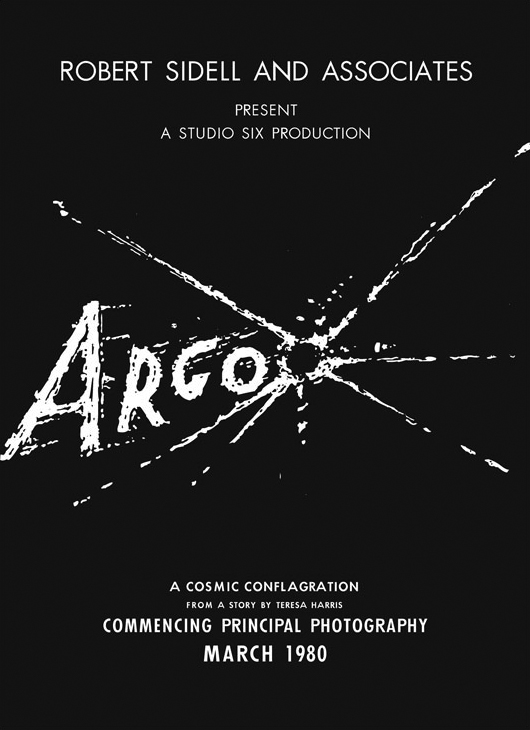

Tony Mendez, meanwhile, worked with members of the film industry to establish the cover back in the United States. He bought an office for the fictional film company Studio Six Productions (named after the six Americans they hoped to rescue), staffed it with operatives in on the mission, took out advertisements in magazines and on billboards, and printed flyers for the non-existent movie, which they called Argo, with the aim of making the operation look legitimate. He also enlisted the help of heavyweight makeup and set specialist John Chambers, who had just won an Oscar for his work on the movie Planet of the Apes (he would go on to be awarded the CIA’s Intelligence Medal of Merit for his help, one of the rare non-CIA members to be so decorated). Despite trying to keep his involvement under wraps, word got out that Chambers was working on a secret big project, and the hype and media attention that resulted actually helped further add credibility to the cover story Mendez was going to use.6 After getting the personal go-ahead from President Jimmy Carter for the mission to proceed, Mendez entered Iran and made contact with the hidden Americans, surprising them at dinner one night, and told them the plan and the roles he had prepared. He then explained the cover story and presented Kirby’s drawings, the script, the ad in Variety, and the telephone number of the Studio Six office back on Sunset Boulevard. Mendez handed out the business cards and passports. Cora Lijek would become Teresa Harris, the writer. Mark was the transportation coordinator. Kathy Stafford was the set designer. Joe Stafford was an associate producer. Anders was the director. Schatz, the party’s cameraman, received the scoping lens and detailed specs on how to operate a Panaflex camera.7

Of course, the covers came with disguises. Cora Lijek had used sponge curlers to give herself a Shirley Temple look. She thumbed through the script as they waited. Kathy Stafford donned heavy, bohemian-looking glasses, pinned up her hair, and carried a sketch pad and folder with Kirby’s concept drawings. Mark Lijek’s dirty-blond beard had been darkened with mascara. Anders thought of their escape as an adventure and flung himself into his role as Argo’s flamboyant director: he appeared in a shirt two sizes too small, buttoned only halfway up his hairy chest to reveal an improvised silver medallion, [and he also] wore sunglasses [and] combed his hair over his ears. Schatz played with his lens.8

After doing some dry runs and rehearsals to better prepare the six Americans for the journey, the Canadians began secretly preparing to abandon their embassy, packing up and beginning to destroy sensitive documents and information, while starting to decrease the number of workers at the embassy. Mendez and the six left for the airport, before encountering some problems. The Swissair flight they had scheduled had had a mechanical failure that was delaying departure, leaving the party stuck in the airport right in front of Iranian security. Mendez briefly looked into switching flights to get on board one that was leaving sooner, before discarding it for fear that would attract unnecessary attention to the group. The problem was fixed eventually however, and the Argo film crew boarded the plane, about to successfully bluff their way out of Tehran. As the plane was about to take off, Mendez remembers, “Bob Anders punched me in the arm and said, “You arranged for everything, didn’t you?” He was pointing at the name lettered across the nose of the airplane. The name of our airplane was “Argau,” a region in Switzerland. We took it a sign that everything would be all right.”9 Later that same day, the Canadians fled their embassy and left Iran as well.

Kathleen Stafford reminisced on the moment their escape succeeded. “We arrived in Switzerland and traded in our Canadian passports for our very own U.S. diplomatic passports, and went to stay in the American Ambassador’s residence. It was beautiful and felt so very great to be out and safe from harm. There we met Sheldon Krys, a dear and familiar face, and he had a State Department doctor with him in case we needed any medication or care… I remember it being dark in our little van as we were driving on the highway with the radio on and they said the escaped hostages are just crossing into Germany, as if the press had a GPS system on the car or something. We were left with our mouths open!”10

As it turned out, select members of the media had discovered the operation. Jean Pelletier, the Washington correspondent of the Canadian newspaper La Presse, had managed to put the pieces together, noting discrepancies in the number of hostages US officials said that the Iranians were holding prisoner. Refusing to believe that the United States did not know the exact number of hostages, he guessed that some workers at the Embassy had managed to escape. “Told by the Minister at Canada’s Washington Embassy, Gilles Mathieu, that Canada was “the most useful American ally in the crisis,” Pelletier logically assumed that the American escapees were harbored by Canadians. He approached the Embassy for confirmation of his guesswork, thus revealing to Canadian authorities that the secret was out.”11 Pelletier, however, had realized the danger of the information he held. It was a career making story, the kind reporters and journalists only dream of making—but going public would endanger the fugitives. He agreed to hold off on breaking the story until the Americans were safely out of Iran, though he did inform Canadian officials that other journalists might not make the same decision he had, moving up the timeline for the rescue operation.

The positive response to the return of the six Americans was overwhelming, and America wasted no time in expressing their gratitude to Canada. “Where other allies had nervously shunned sanctions and offered only rhetoric against Iran, Canada had literally come to the rescue. In Detroit, billboards facing Canada suddenly sprouted Canadian maple leaves and appreciative messages like THANK YOU, CANADA. The Canadian embassy switchboard in Washington was overwhelmed by Americans wishing to convey warm sentiments: “Brilliant move.” “Courageous feat.” “Well done.” In Fergus Falls, Minn., Radio Station KBRF got an enthusiastic response to its suggestion that listeners send I LOVE YOU valentine messages to Flora MacDonald, Canada’s Secretary of State for External Affairs, who, as her nation’s top diplomat, had proudly confirmed the rescue story.”12 In the end, the other American hostages who had been captured by Iran were released to the United States minutes after the swearing in of President Ronald Reagan in 1981. The involvement of the CIA remained classified for years after the rescue, only coming to light when government documents were declassified in 1997.

- Richard Foot, Norman Hillmer, “The Canadian Caper”, October 2019, Encyclopedia Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/event/Canadian-Caper ↵

- Joshua Bearman, “How the CIA Used a Fake Sci-Fi Flick to Rescue Americans From Tehran”, April 2007, WIRED, https://www.wired.com/2007/04/feat-cia/ ↵

- Antonio J. Mendez, “A Classic Case of Deception : The CIA Goes Hollywood”, April 2007, Central Intelligence Agency, Studies In Intelligence, https://www.cia.gov/static/48176093196e51d95219f3e3e762f038/Classic-Case-of-Deception.pdf. ↵

- Richard Foot and Norman Hillmer, “The Canadian Caper,” October 2019, Encyclopedia Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/event/Canadian-Caper. ↵

- “The Canadian Caper, Argo, and Escape from Iran,” October 2015, Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training, https://adst.org/2015/10/the-canadian-caper-argo-and-escape-from-iran/. ↵

- Antonio J. Mendez, “A Classic Case of Deception : The CIA Goes Hollywood,” April 2007, Central Intelligence Agency, Studies In Intelligence, https://www.cia.gov/static/48176093196e51d95219f3e3e762f038/Classic-Case-of-Deception.pdf. ↵

- Joshua Bearman, “How the CIA Used a Fake Sci-Fi Flick to Rescue Americans From Tehran,” April 2007, WIRED, https://www.wired.com/2007/04/feat-cia/. ↵

- Joshua Bearman, “How the CIA Used a Fake Sci-Fi Flick to Rescue Americans From Tehran,” April 2007, WIRED, https://www.wired.com/2007/04/feat-cia/. ↵

- Antonio J. Mendez, “A Classic Case of Deception : The CIA Goes Hollywood,” April 2007, Central Intelligence Agency, Studies In Intelligence, https://www.cia.gov/static/48176093196e51d95219f3e3e762f038/Classic-Case-of-Deception.pdf. ↵

- “The Canadian Caper, Argo, and Escape from Iran,” October 2015, Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training, https://adst.org/2015/10/the-canadian-caper-argo-and-escape-from-iran/. ↵

- “Ken Taylor and the Canadian Caper,” June 2019, Government of Canada, https://www.international.gc.ca/gac-amc/history-histoire/ken-taylor.aspx?lang=eng. ↵

- “Canada to the Rescue,” Time, Feb 11, 1980, https://web.archive.org/web/20110120111357/http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0%2C9171%2C950226%2C00.html. ↵

Tags from the story

American Embassy

Iranian Revolution of 1979

Ken Taylor

Robert Anders

Studio Six Productions

Tony Mendez

Stephen Talik

Howdy. I’m Stephen Talik, a native Texan born in College Station, and an Eagle Scout. I find history – especially the World Wars, Cold War, and the espionage world – fascinating. I also enjoy learning about the newest and coolest gadgets for technological use and internet security, and watching sports. I have also interned in the Washington D.C. office of a member of Congress, and I am a Political Science Senior at St. Mary’s University.

Author Portfolio PageRecent Comments

Aaron Sandoval

This article was very well written, and the author did a good job of covering the topic. While I had heard of the topic, I had little knowledge of the extent as to what occurred and the role that the Canadian embassy played. The details and the quotes used by the author made the story not only easier to follow but to visualize.

22/04/2021

8:43 am

Faith Chapman

The stuff that the Americans did to give thanks to the Canadians, like sending the valentine messages, was so incredibly wholesome; it made me smile. The curious thing is, I had learned about the hostage situation with the American ambassadors/workers in Iran, but I’ve never heard about Canada’s involvement in rescuing the ones that escaped, or that there were even people that had escaped at all. I wonder why, but I was able to enjoy reading this more because it felt like I was reading another side of the story I knew.

11/04/2021

8:43 am