December 8, 2017

The Civil War and the Birth of the Emancipation Proclamation

Imagine being kidnapped or sold into captivity, forced into submission through violent beatings, torture, and intimidation, sold on the auction block to the highest bidder, and being forced to work for free under the most cruel conditions. And imagine that it is all perfectly legal. This was the reality for blacks who endured the horrific institution of enslavement in our nation’s early years. For enslaved blacks, it was more than being forced to work without compensation, but a way of life.

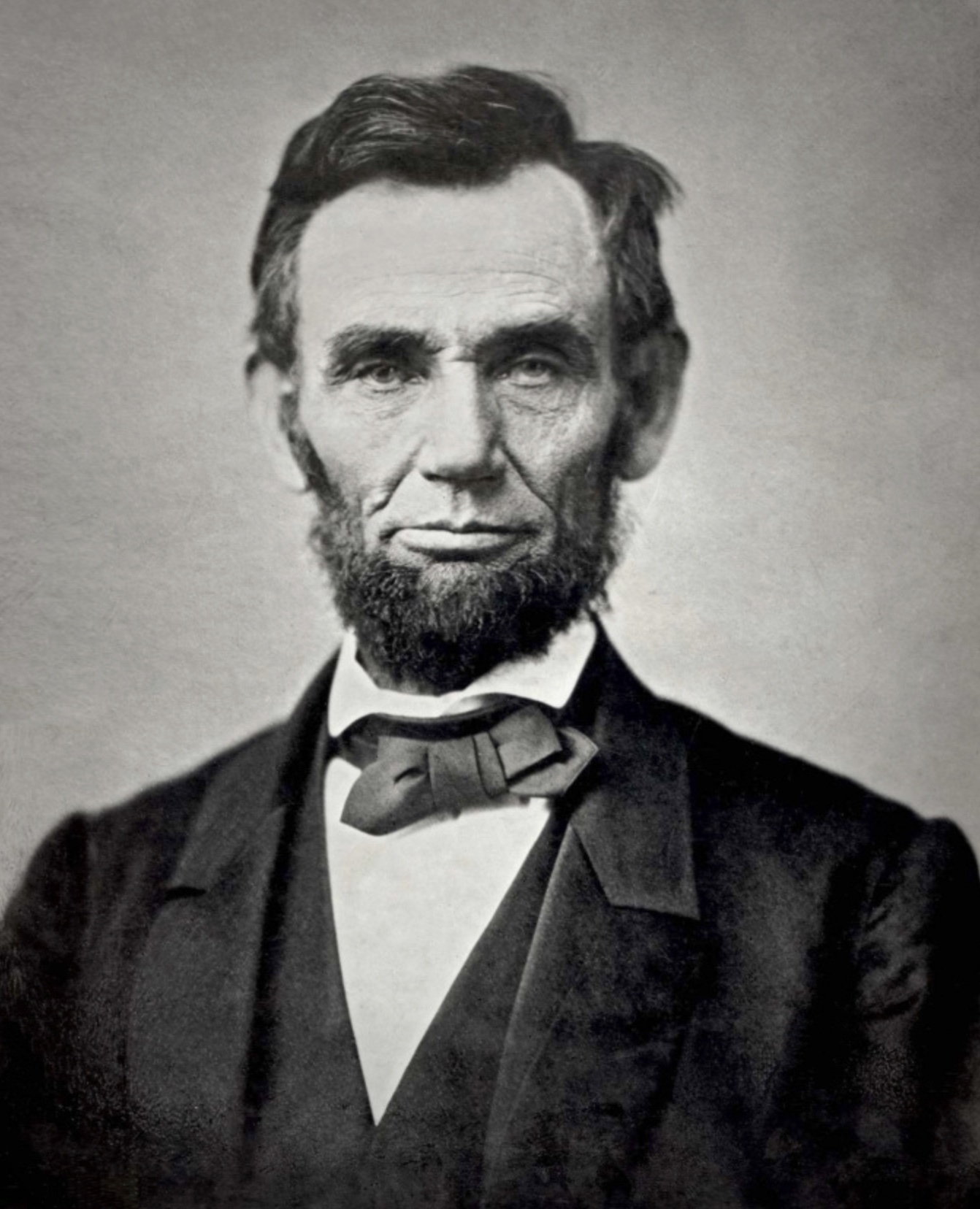

It’s 1861, and the American Civil War has just begun, with Abraham Lincoln as President of the United States. The northern States are excelling in manufacture, while the southern States, based on a system of large-scale farming, depend on the labor of African-American slaves to grow their crops. Growing abolitionist sentiment in the North after the 1830s and northern opposition to slavery’s extension into the new western territories, led many southerners to fear that the existence of slavery in America was in danger.1

On November 6, 1860 Abraham Lincoln was elected President. It was a result that outraged the southern states. The Republican party had run on an anti-slavery platform, which led the southerners to believe that they were not welcome in the Union. One month later, on December 20, 1860, South Carolina became the first southern state to secede.2 As tensions grew stronger against Lincoln, by February 1, 1861, six more states—Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, and Texas—had seceded from the Union. These states formed the Confederate States of America, with Jefferson Davis, a Mississippi Senator, as their provisional president.

Lincoln felt it his duty as president to maintain the Union. Doing so, he never committed to the ending of slavery or getting rid of the Fugitive Slave Law. However, Lincoln’s comments were not enough to satisfy the Confederacy. This lead them to attack on April 12, 1861 Fort Sumter in South Carolina, which began the Civil War. To keep the Union together, Lincoln insisted that the war was not about slavery, but about preserving the Union. His words were not aimed at the southern states; however, the majority of northern white farmers were not interested in fighting for the freedom of southern slaves, nor give any African Americans any rights.3

Because there was no consistent policy regarding fugitives once the war began, the government had a difficult time deciding what to do with escaped slaves. This led to individual military commanders making their own decisions regarding the thousands of slaves seeking the protection of the Union army. On August 6, 1861, a solution was established, that fugitive slaves would be considered “contraband of war” if their labor had been used to aid the Confederacy in any way. If any were found to be in contraband, they were declared to be free, and subject to the protection of the Union army. Although the contraband slaves were declared free, Lincoln insisted that the purpose of the war was still to save the Union, not to free slaves.4 The occasion for changing this stance came about as a result of the Battle of Antietam.

The battle had taken place near Antietam Creek in Sharpsbug, Maryland. On September 16, 1862, the Confederate Army and the Union Army both contributed to the bloodiest day in American history, with 23,000 casualties. No other single day in American history before or since has been so deadly. Nearly one out of every four soldiers engaged was a casualty: killed, wounded, or captured. The violent fighting would be remembered by many who were there as the most intense of the war. Until the Battle of Antietam, the Confederate army had been focusing on a defense strategy. The majority of their major battles had all been fought on Southern soil. However, after the achievement of the Second Battle of Bull Run, General Lee had decided that it was the appropriate time to start focusing more on their offense than defense. It was September 3, 1862, when the Confederate army, led by General Robert E. Lee, entered the state of Maryland. Their hope was to invade the north all the way to Pennsylvania. Both General Lee and Jefferson Davis, Confederate President, believed that a successful invasion would convince France and Great Britain to officially recognize the Confederacy as a nation, and perhaps even enter the war on their behalf. The Union held off the invasion of the Confederacy at Antietam, although President Abraham Lincoln was not satisfied that the Confederates were able to retreat back to Virginia. However, the battle was declared a Union victory and Lincoln followed the battle with the Emancipation Proclamation, which officially made slavery a second cause of the war.5

On July 22, 1862, Lincoln read a draft of the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation to his cabinet. On this document, it announced “…that all persons held as slaves within said designated States, and parts of States, are, and henceforward shall be free; and that the Executive government of the United States, including the military and naval authorities thereof, will recognize and maintain the freedom of said persons.”6 Secretary of State William H. Seward was on board with Lincoln, but persuaded him to wait until the Union had had a victory before issuing the document. After the Union victoriously won the Battle of Antietam, it was time for Lincoln to issue the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation on September 22, 1862. It warned the Confederate states to quit the war and surrender by January 1, 1863, or their slaves would be proclaimed freed. Lincoln was giving the South a choice: end the war now and keep your slaves, or keep fighting and risk losing the war and the institution of slavery. However, many argued that the proclamation didn’t actually free any slaves or destroy the institution of slavery itself—it still only applied to states in active rebellion, not to the slave-holding border states or to rebel areas already under Union control. In reality, it simply freed Union army officers from returning runaway slaves to their owners under the national Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. Despite all opposition, Lincoln was firm and officially pronounced the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863.”That on the first day of January, in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and sixty-three, all persons held as slaves within any State or designated part of a State, the people whereof shall then be in rebellion against the United States, shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free.”7 Those words were issued by Abraham Lincoln on the final draft of the Emancipation Proclamation. In the midst of the struggle, Lincoln drafted his Emancipation Proclamation, calling for the freedom of the slaves. Months later, in November, he delivered his most famous speech, the Gettysburg Address. This speech summed up the principles for which the federal government still fought to preserve the Union.8

The purpose of the Civil War changed during the war. The North was not only fighting to maintain the Union, as it had at the beginning of the war, but it was also fighting to end slavery. African Americans rushed to enlist, once the proclamation was established. The Union army eventually consisted of over 179,000 African-American men that served in over 160 units. The 179,000 men both included free African Americans from the North and runaway slaves from the South who enlisted to fight. Even though there had been African Americans who had served in the army and navy during the American Revolution and in the War of 1812, none were able to enlist due to a 1792 law that stripped them from bearing arms in the U.S. Army. President Abraham Lincoln also had concerns over accepting African American men into the military, too. Doing so might persuade border states like Maryland, Kentucky and Missouri to secede. Black soldiers faced discrimination as well as segregation into “Black” units, and some only earned $7 per month, plus a $3 clothing allowance, while white soldiers commissioned $13 per month, plus $3.50 for clothes.9

On April 18, 1865, the Civil War ended. The Confederate army surrendered to the Union army. Approximately 620,000 Americans died in the four-year war, with tens of thousands injured. In January 1865, a new chapter in American History opened as the 13th Amendment was passed, which officially abolished slavery in the United States and freed more than four million African Americans. More importantly, the 14th Amendment was passed in June 1865, which granted citizenship to all people born in the United States, and for the first time, granted citizenship to all former slaves. In 1869, the 15th Amendment was passed, which guaranteed the right for any American male citizen to vote no matter what their race. The Civil War was a significant event in United States history. It showed that the North’s victory proved that democracy worked. Also it was a huge step for the African-American people, to fight for what they deserved…freedom.

- “The Emancipation Proclamation,” Emancipation Proclamation (Primary Source Document) (August 2017): 1. ↵

- Brian Lamb and Susan Swain, Abraham Lincoln Great American Historians on our Sixteenth President (New York: Public Affairs, 2008), 56-61. ↵

- Allen C. Guelzo, Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation: the end of slavery in America (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2004), 90-100. ↵

- Allen C. Guelzo, Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation: the end of slavery in America (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2004), 159. ↵

- James M. McPherson, Crossroads of freedom: Antietam (Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press, 2002), 68-72. ↵

- “The Emancipation Proclamation,” Emancipation Proclamation (Primary Source Document). ↵

- “The Emancipation Proclamation,” Emancipation Proclamation (Primary Source Document). ↵

- Salem Press Biographical Encyclopedia, January 2015, s.v. “Abraham Lincoln,” by Joseph E. Suppiger. ↵

- Brian Lamb and Susan Swain, Abraham Lincoln Great American Historians on our Sixteenth President (New York: Public Affairs, 2008), 74-75. ↵

Tags from the story

Abraham Lincoln

American Civil War

Emancipation Proclamation