May 6, 2018

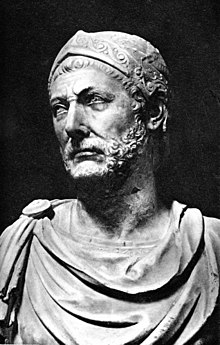

The Enemy of Rome: Hannibal and the Second Punic War

Hannibal Barca may have been one of the greatest generals that ever existed in the ancient world. He played a major role in the Second Punic War, which involved Carthage against the Roman Republic. In the Second Punic War, Hannibal managed to defeat every Roman army that faced him off and on the battlefield. During these battles, Hannibal was severely underestimated and he was able to use this to his advantage. This was mostly due to the fact that Romans thought that the Second Punic War would be a swift victory, but that wasn’t the case. One by one, Rome’s troops fell as Hannibal’s tactics brought Rome to its knees and caused Rome to go into full-blown paranoia. They feared that Hannibal might attack Rome any day, but luckily for them, Hannibal decided not to take Rome by force. Ultimately, his intellect and military prowess got the best of him and led him to his dreadful demise.

Hannibal was born into a military family and was forged to be an unbeatable military commander since childhood. His father was Hamilcar Barca, an important general of the Carthaginian army during the First Punic War. As a child, Hannibal was able to live among his fellow soldiers where he would gain experience and strategies that made him one of the greatest generals to have ever lived.1 At the age of twenty-six, Hannibal assumed command of the mighty Carthaginian troops.2 Not only did the men see Hannibal as a fierce warrior but also as a leader. As Hannibal ascended into power, he only had one goal in mind: to make Rome pay. Rome had taken Sicily and Sardinia from the Carthaginian empire and excluded Carthage “from all waters west from Italy” after the First Punic War.3 All he needed was an excuse to begin another war with Rome.

An opportunity soon rose for Hannibal in 219 BCE when Rome decided to intervene in the political affairs in the Spanish city-state of Saguntum after one of the Carthaginian treaties specifically forbade the intervention in any foreign affairs.4 This meant that Rome knowingly and willingly decided to violate its treaty with Carthage. Ultimately this led Hannibal to attack Saguntum as they failed to uphold the treaty and because of their strategic fortified position that might one day be used by the Romans to attack Carthage again. After only eight months of siege, the city fell.5 With this significant victory in place, Hannibal realized that he could expand the Carthaginian empire to the northern peninsula. He also realized that he might be able to achieve his father’s dream to lay waste to Rome once and for all. Immediately after the siege of Saguntum, Rome demanded that Carthage surrender Hannibal after he laid waste to Saguntum, an ally of Rome. Carthage refused to surrender Hannibal, so the Romans did what every Roman would do: declare war on Carthage for not complying with Rome’s demand.6 This began the Second Punic War, a major war where Rome was nearly wiped out of history by the Carthaginian army.

As the war began, Hannibal was already prepared with an army of enthusiastic troops who were eager to lay waste to Rome and gain their honor back.7 He also thought of multiple attack plans that he could unleash on Rome, with ideas so unprecedented that not even Rome could have predicted them. His idea was so audacious that not even his brother, Hasdrubal, a general of the Carthaginian army, would dare to lead his men through such a path. The plan was to have his army march from New Carthage, Spain, through Gaul, or modern France, and across the intrepid Alps in order to reach the Italian peninsula. His plan was by far the most dangerous path because the Alps were tricky and treacherous, and not many people were able to survive them, due to its extremely cold weather and treacherous terrain. All of this made it a risky proposition because there was a possibility that Hannibal might lose a large portion of his army during the endeavor. This plan was one of Hannibal’s best ideas due to the fact that Carthage could not attack by sea as Rome controlled the Mediterranean Sea. Nor could they take the normal roads that led to Rome, as they were heavily fortified with Roman legions.8 So, this made the Alps the best chance for Hannibal to catch the Romans off guard.

Ultimately, Hannibal departed from New Carthage with sixty-thousand men and took the arduous journey across the Alps. When Hannibal reached the Italian peninsula, only one-third of his army and several elephants survived the treacherous journey.9 His march lasted eight months and it led Hannibal to the Po River Valley, where an army of Roman soldiers had caught wind of Hannibal’s arrival. Although Hannibal was severely outnumbered, the Carthaginians fought well and managed to defeat the Romans.10 In the meantime, Hasdrubal Barca was left behind in Spain in order to ensure that it was well protected in case that Rome decided to attack. Sure enough, Hannibal’s intuition was right once again.

After Hannibal arrived to the Italian peninsula, he was encountered by Roman legions. They were led by Publius Cornelius Scipio and the Battle of Trebia in 218 BCE. Even before the battle started, Hannibal caught the Roman army off guard and this led to Hannibal’s first monumental victory of the war.11 Rumors then began to spread throughout the Roman Republic of Hannibal’s intellect and military genius. Eventually, these rumors managed to reach the Celts, who lived in Gaul, and they decided to create an alliance with Hannibal because they too sought the destruction of Rome. This new addition to Hannibal’s army increased it from twenty-thousand to about fifty-thousand men. Most of these men were Celtic recruits that would play a crucial role in Hannibal’s tactics during the coming battles.12

With these new additions to his army, Hannibal had enough men to move towards Rome. First, he encountered Gaius Flaminius in the Battle of Trasimenus in 217 BCE. Here virtually all of the Roman soldiers were killed after Hannibal delivered a surprise blow to the Romans, who chased after Hannibal’s army throughout the countryside. This marked Hannibal’s second monumental victory in the war. These first two victories came at a cost to the Carthaginians, who lost ten-thousand soldiers. Nearly a year later, in the August of 216 BCE, Hannibal’s army of forty-thousand men confronted an army of eighty-thousand Romans in the Battle of Cannae. Little did Hannibal know that his arch nemesis, Scipio Africanus, stood on the other side of the field, ready to strike the Carthaginian army.13 Nobody could have predicted the aftermath of this battle, because Romans outnumbered the Carthaginian army two to one, which should have meant a clear victory for Rome. Instead, the Romans underestimated the Carthaginian army, who ended up victorious. This battle was marked as Hannibal’s third major victory.

During this time, the Roman Senate grew worried that Hannibal might attack and lay waste to Rome. This would have been the perfect time for Hannibal to attack Rome because they were paranoid and scared of Hannibal and his army. Ultimately, Hannibal decided to not attack Rome because he thought that it was too fortified and instead, he hoped for a rebellion to occur on the inside of Rome. This would be a decision that Hannibal would come to regret because the rebellion that he patiently waited for never occurred. Another reason for why Hannibal opted not attack Rome directly was because he hoped that Rome’s allies would turn on Rome and join his army. Unfortunately, many of Roman allies remained loyal and faithful to Rome, no matter how bad the situations became.

While Hannibal waited and roamed through the Italian peninsula, Rome devised a plan to send new and more efficient forces to New Carthage, along with their leader Scipio Africanus. Scipio was present in the Battle of Cannae and had been able to successfully escape the terrible massacre. After he witnessed Hannibal’s intellect first-hand, Scipio began to train for his next endeavor with Hannibal. He was able to adopt new tactics and better weapons from weaponry advances in Rome.14 By 210 BCE, Scipio was appointed as a proconsul and was sent to New Carthage to defeat Hasdrubal. At the first, the Hasdrubal’s forces were able to give a good fight but ultimately were defeated in 206 BCE. This proved to be a great advantage to Rome because they destroyed any possible outside help that Hannibal could receive during his campaign.15 After his swift victory in New Carthage, Scipio returned to Rome and was granted the title of consul, the highest position a Roman could have during the Republic. His first decision as Consul was to attack Carthage with all of Rome’s power. This critical decision became the start of Hannibal’s downfall.

Scipio managed to convince the Senate to attack Carthage with an army thirty-five thousand strong and he arrived at Carthage in 204 BCE.16 Here, Scipio would wreak havoc on Carthage just as Hannibal had on the Roman Republic. It soon reached a point where Hannibal and his army needed to abandon his campaign on Rome to lend a hand to the now weakened Carthaginian army. As events unfolded, Hannibal would reach Carthage, the land where it all began, and both the Roman and the Carthaginian army would meet face to face in the Battle of Zama, which determined who would emerge the victor of the Second Punic War.

In this battle, both sides reached a critical point where both sides were toe to toe. Luckily, Scipio’s cavalry provided major field superiority when they struck a final blow to the Carthaginian infantry. After this significant blow, Hannibal’s army now fought a two-sided battle that the Carthaginians couldn’t win.17 Hannibal’s veteran infantry “fought grimly, they were cut into pieces” and this event was marked as Cannae but in reverse, because now the Romans had the Carthaginians surrounded.18 The defeat at the Battle of Zama meant that Hannibal’s army was finally defeated for good. After seventeen years, the Romans fought and suffered countless deaths. This battle marked the end of the Second Punic War.19

Unfortunately for Rome, Hannibal’s fight against them wasn’t over just yet. As Hannibal grew older, he continued to wage war on Rome with the small armies of Bithynia. It wasn’t until he committed suicide in 182 BCE that Rome’s greatest enemy finally met his end.20 Although Hannibal met a tragic end, his legend has been able to live on and he has been named one of the greatest generals that has ever been seen in the ancient world, only topped by Alexander the Great.

- Salem Press Biographical Encyclopedia, 2013, s.v. “Hannibal,” by Larry W. Usilton. ↵

- Salem Press Biographical Encyclopedia, 2013, s.v. “Hannibal,” by Larry W. Usilton. ↵

- Leonard Cottrell, Hannibal, Enemy of Rome (New York: Rinehart and Winston, 1961), 10. ↵

- Salem Press Biographical Encyclopedia, 2013, s.v. “Hannibal,” by Larry W. Usilton. ↵

- Salem Press Biographical Encyclopedia, 2013, s.v. “Hannibal,” by Larry W. Usilton. ↵

- Salem Press Biographical Encyclopedia, 2013, s.v. “Hannibal,” by Larry W. Usilton. ↵

- Leonard Cottrell, Hannibal, Enemy of Rome (New York: Rinehart and Winston, 1961), 17. ↵

- Salem Press Encyclopedia, 2013, s.v. “Second Punic War,” by Robert D. Talbott. ↵

- Salem Press Encyclopedia, 2013, s.v. “Second Punic War,” by Robert D. Talbott. ↵

- Salem Press Biographical Encyclopedia, 2013, s.v. “Hannibal,” by Larry W. Usilton. ↵

- Salem Press Biographical Encyclopedia, 2013, s.v. “Hannibal,” by Larry W. Usilton. ↵

- Salem Press Biographical Encyclopedia, 2013, s.v. “Hannibal,” by Larry W. Usilton. ↵

- Leonard Cottrell, Hannibal, Enemy of Rome (New York: Rinehart and Winston, 1961), 136. ↵

- Salem Press Biographical Encyclopedia, 2013, s.v. “Scipio Africanus” by R. C. Lutz. ↵

- Salem Press Biographical Encyclopedia, 2013, s.v. “Scipio Africanus” by R. C. Lutz. ↵

- Salem Press Biographical Encyclopedia, 2013, s.v. “Scipio Africanus” by R. C. Lutz. ↵

- Salem Press Encyclopedia, 2013, s.v. “Battle of Zama,” by Jeffery L. Buller. ↵

- Leonard Cottrell, Hannibal, Enemy of Rome (New York: Rinehart and Winston, 1961), 238. ↵

- Leonard Cottrell, Hannibal, Enemy of Rome (New York: Rinehart and Winston, 1961), 239. ↵

- Salem Press Biographical Encyclopedia, 2013, s.v. “Hannibal,” by Larry W. Usilton. ↵

Tags from the story

Hannibal Barca

Rome

Scipio Africanus

Second Punic War

The Battle of Zama