March 24, 2017

The Incident on King Street: the Boston Massacre of 1770

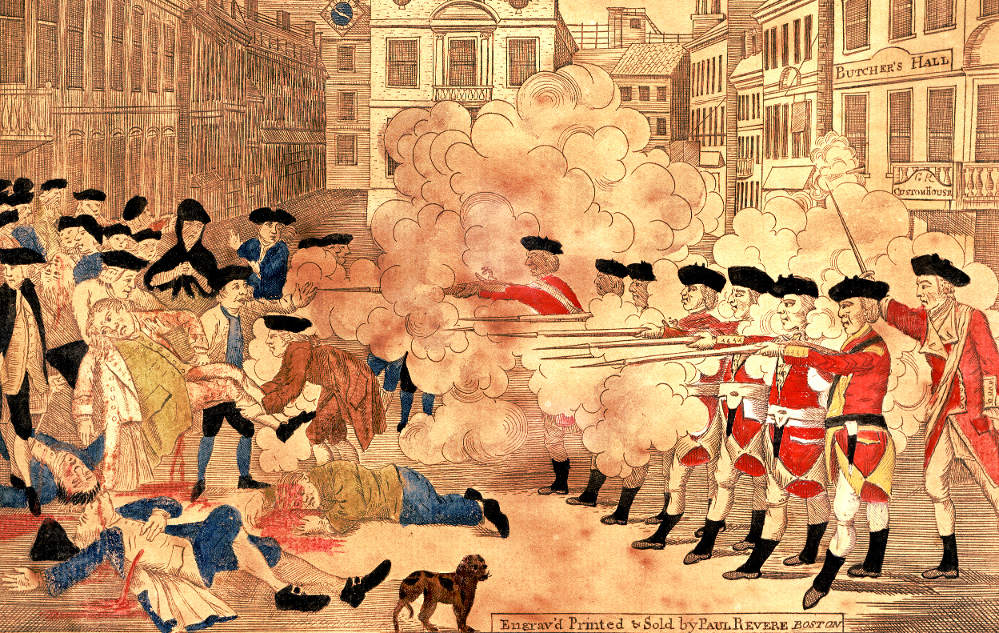

On the day of March 5, 1770, roughly around 9:00 p.m. in Boston, Massachusetts, the tension between the Boston colonists and the British soldiers had reached its breaking point. Soldiers at this time were stationed in the colonies to protect and support the colony’s officials implementing the unpopular taxes on the colonists. Eight soldiers and one officer of the Twenty-ninth Regiment had been guarding the Custom-House on King Street when a mob of angry colonists, who were upset about the unfair taxes imposed on them by King George III, began to rally around them. The altercation had begun with the colonists verbally threatening the soldiers, but little by little things became worse. The colonist began to throw rocks and snowballs, and were even taking swings at the soldiers with clubs. Without being given the order to fire upon the colonists, the soldiers began to fire their muskets into the crowd of colonists, instantly killing three people in the mob and wounding eight others, two of whom were later pronounced dead. The five “victims transformed into the first martyrs of American independence,” wrote Hiller B. Zobel. The shooting became known as the Boston Massacre to all people in the colonies and as The Incident on King Street to the people of Great Britain.1

Patriots in Boston, such as Samuel Adams and Paul Revere (who painted the famous depiction of the soldiers firing on the crowd), were quick to have their local papers write about the shooting, labeling it a senseless act of violence on innocent by-standers. They believed this would help them get other Bostonians to hate the British soldiers occupying Boston. Shortly after the incident, by-standers were questioned on what had happened just moments ago, some of whom said they not only saw the soldiers on the streets firing on the people, but that they also saw fire coming from the second story of the Custom-House. The rumor was tested by a ballistics expert named Benjamin Andrews. He was able to track a bullet hole on a window from a business right across the street from the Custom-House, and he determined that the bullet came from “just under the stool of the westernmost lower chamber window of the Custom-House.”2 Local government noticed how much this incident riled up the people of Boston, and were committed to giving the soldiers and instigators a fair trial in court in order to prevent the British government as well as the Patriots from retaliating.

The soldiers had a hard time finding a lawyer to argue their case in court. Officer Preston, however, called for the future president and leading patriot John Adams to defend them. It was said that John Adams agreed to defend Officer Preston and the rest of the soldiers involved in the shooting in order to guarantee a fair trial for them. The town of Boston hired prosecutors Samuel Quincy and Robert Treat Paine to handle the cases of Officer Preston and the soldiers who were involved in the incident. Officer Preston and his soldiers were tried in separate trials.3

Seven months later, in October 1770, Officer Preston’s trial was held. After a lengthy trial, the jury in the case agreed that Officer Preston had not ordered his soldiers to open fire on the angry mob, and ultimately decided that he was not guilty of manslaughter, and he was acquitted from the crime. In the trial held for the soldiers, six of the eight were also found innocent and were acquitted; the two remaining soldiers were not so lucky. The last two soldiers were found guilty of manslaughter and were branded on the thumb as punishment, and then set free. Some people felt that the punishment did not fit the crime, but aside from the branding of the two soldiers, all soldiers involved in the Boston Massacre were withdrawn from the town and were “removed to the castle in the harbor” and were no longer there to enforce the unfair taxes on the people of Boston.4

- Hiller B. Zobel, “The Boston Massacre,” The William and Mary Quarterly, Vol. 27, No. 4, (1970): 675. ↵

- O. M. Dickerson, “The Commissioners of Customs and the ‘Boston Massacre,’” The New England Quarterly Vol. 27, No. 3, (1945): 317. ↵

- Louise Phelps Kellogg, “The Paul Revere Print of the Boston Massacre, “The Wisconsin Historical Magazine of History, Vol. 1, No. 4, (1918): 377-387. ↵

- Louise Phelps Kellogg, “The Paul Revere Print of the Boston Massacre, “The Wisconsin Historical Magazine of History, Vol. 1, No. 4, (1918): 378. ↵

Tags from the story

Boston Massacre

John Adams