December 9, 2017

The Johnstown Flood of 1889: A Preventable Disaster

What comes to mind when you hear the word “geology”? Do you think of a scientist in a lab coat? Do you envision an explorer on some mountain top? Does your mind show you a pile of rocks? Well, geology is all of the above. Geology, as defined by Merriam-Webster is “a science that deals with the history of the earth and its life, especially as recorded in rocks.” To the average person this may not sound exciting, but it is one of the most important sciences we have. And, ignoring the warning signs in the natural environment can spell out disaster for any community. And, while there is nothing that can be done to stop natural disasters completely, we can avoid dangerous areas and work to protect our towns and cities as much as possible. The Johnstown Flood is a perfect example of this. It demonstrates what happens when we ignore natural geology in our environment, because we are very susceptible to loss of life due to natural disaster.

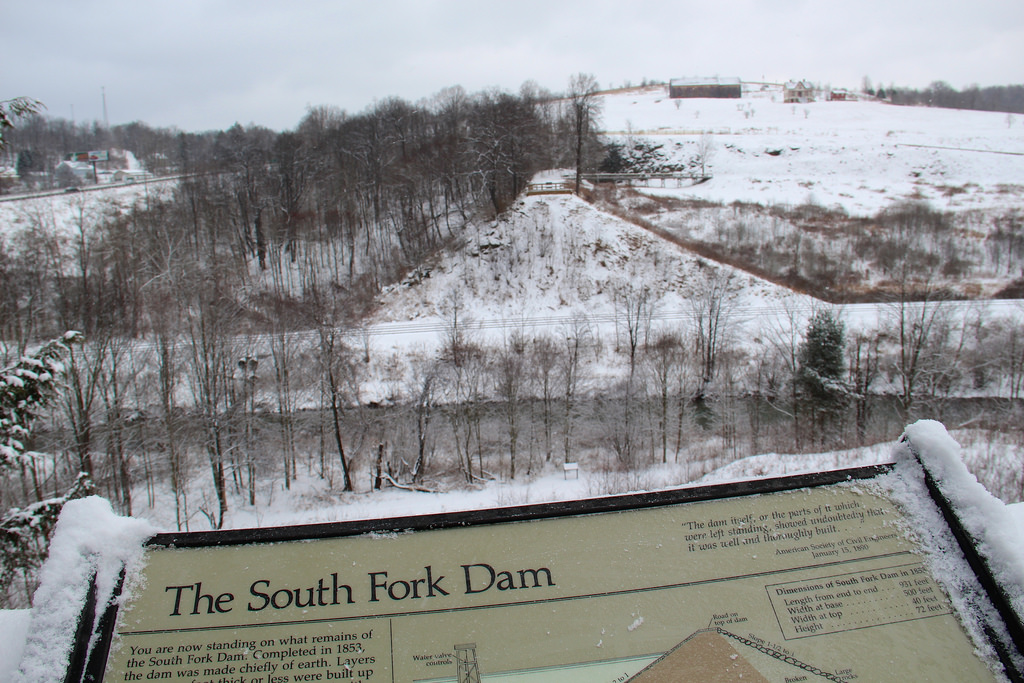

To truly understand the devastation caused by this flood, we need to understand the construction of the South Fork Dam. This dam was built in 1840 as a reservoir for the Pennsylvania Mainline Canal.1 Its purpose was to hold water for the canal during dry seasons.2 Pennsylvanian engineer William Morris designed the dam, located a “safe” distance fourteen miles upstream from the city of Johnstown. Constructing this massive structure was no easy feat. The floor of the valley was cleared to bare rock, upstream clay was layered in sections two feet thick and then submerged underwater for several days. This technique, known as “puddling,” is meant to create a watertight barrier so that stone and shale could then be placed at the core. This mixture, called “riprap,” is meant to strengthen the wall of the dam so it won’t be weakened by water washing against the wall.3

Officially the “Western Reservoir,” known locally as the South Fork Dam, was massive in size, at 918 feet across the valley and seventy-two feet in height. The rock used in construction was ten feet thick at the top of the dam and 220 feet thick at the base, and many of the rocks used weighed over ten tons. Obviously, this dam was built to last.4

Sadly, it did not last as a canal reservoir. Twice during the construction period, building on it had to be stopped because of financial issues. It was finally completed June 10, 1852, but not deemed safe for operation until 1883.5 Engineers also decided that it would be unsafe to fill the dam with more than forty feet of water for the first two years. But when a lack of rain depleted the reservoir past the forty feet, two leaks were found and the dam had to be drained for repair.6

But in 1852, the Pennsylvania Railroad service opened, and with it came the financial failure of the canal system, since the railroad was able to deliver goods cheaper, faster, and safer than the canal. The state of Pennsylvania put the canal system up for sale, including the South Fork Dam. Ironically, the canal system and the dam were bought by the Pennsylvania Railroad system in 1857, only five years after its completion.7

The early period of the dam parallels the period of the rapid industrialization of America, when railroad building symbolized the entire age. The Pennsylvania Mainline Canal went out of business in 1854, two years after the construction of the South Fork Dam and the arrival of the Railroad system.8 It’s no surprise that the Railroad was as successful as it was, by offering safe transportation of people and goods across miles of landscape; it became the most economical way to travel. Pennsylvania became a pioneer in the beginning stages of railroad system development. Having been chartered in 1846, the railroad system arrived in Pittsburgh in 1852, and by 1860 it already had mileage of 2,598. Soon after, in 1865, the railroad expanded to New York, Washington, Buffalo, Chicago, and even as far as St. Louis, Missouri.9 The railroad gave birth to a whole new economy and many new industries, offering new opportunities for people to make money and follow their “American Dream.”

Ten years after being finished, while under the possession of the railroad system, the dam suffered a major break. The upstream portion of the stone culvert under the dam collapsed.10 This break resulted in a minor flood in Johnstown, where water only rose about two feet and did not cause much damage.11

The following year, in 1863, a canal between Johnstown and Blairsville was closed. And because of this closure, maintenance of the dam ceased. Later, in 1875, US Congressman and Pennsylvania Railroad employee John Riley bought the dam and removed five drainage pipes at the base of the dam. This caused a sag at the top of the dam, which made it easier for water to overflow. Another consequence of removing these pipes was eliminating all safe options for removing or draining excess water.12

By now, the dam was not being used at all. In 1879, the dam was bought by a man named Benjamin Ruff. His dream for the dam was to turn it into an exclusive summer resort for the wealthiest men and women of Pennsylvania.13

The Gilded Age was a profitable time for people all across America. With developments in transit, economy, and labor, men and women could rise up the social and economic ladder faster than ever before. Industries like steel manufacturing were easy to grow and prosper in, because of the creation and spread of the railroad. Because of this, jobs and opportunities to make large amounts of money were readily available to the well-positioned. Men often made huge profits from these industries, and became part of the new elite known as “Robber Barrons.” Take for example Andrew Carnegie, a Scottish immigrant who got his start in the Pennsylvania Railroad.14

Beginning as a simple telegrapher, Carnegie handled military messages during the Civil War and eventually entered railroad management. From there he grew in influence and by 1873 he was building his own steel mills, becoming a steel industry titan. And trying to seem like a humble man, he made it his mission to pay back to the world with benign distribution of his vast wealth. Eventually, he sold his steel empire, Carnegie Steel Corporation, to J.P. Morgan in 1901, devoting the rest of his life to charity.15

Ruff bought the dam and the acreage surrounding it, turning it into the South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club. The members of this club were notorious for their wealth and social stature. One of the members of the club was Andrew Carnegie. When Ruff purchased the dam, he inadequately fixed the holes and other damage from the first break on the dam. But he never replaced the drainage pipes. In addition to this, he lowered the top of the dam so it could be wide enough for a carriage to pass through.16 By his doing all of this, it became impossible to drain the dam of excess water. The only option was for it to spill over the top.

All of these actions and failure of infrastructure are what led to the destruction of Johnstown in the biggest natural disaster of the nineteenth century. At around three in the afternoon on May 31, 1889, a wall of water described as forty feet high rushed towards the small town. The South Fork Dam had burst, sending twenty million tons (3.6 billion gallons) of water straight to Johnstown. Carrying fourteen miles worth of debris, the wave decimated the town, sending animals, people, and buildings miles downstream.17

After Johnstown was destroyed, it was found that 1,600 homes had been destroyed, 2, 209 people lost their lives, and there was over $17,000,000 in property damage.18 As soon as news of the disaster spread on what had happened to this town, reporters and illustrators from over 100 magazines and newspapers were sent to describe what happened.19

News of what happened to Johnstown spread across the world. Soon donations from Russia, France, Turkey, Britain, Australia, Germany, and ten other countries were sent to Johnstown. Relief was also sent from every state in the nation, whether it be money, clothing, or food. This was also the largest disaster that the Red Cross had dealt with since its creation.20

The nation was moved by the tragedy that struck the people of Johnstown, and as result, the media sensationalized what happened, and demonized the members of the South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club. Though they were not directly at fault, since damage to the dam had begun much earlier, after its construction, the lowering of the dam height and poor patchwork was the straw that broke the camels back.21

Though, people tried to bring lawsuits against the club and its board, none were successful. The reason was that at the time, natural disasters caused by human activity were not punishable by law. It was not until after this tragic flood that Ryland’s Law was adopted in the twentieth century.22

Originating in the United Kingdom, this law states that negligence does not need to be proven in order for a person, organization, or company, to be found liable for natural disaster caused by man-made structures. This was a historic law. Prior to this, the belief was that disasters caused by man were not something that could be punishable in a court of law. But, after the devastation in Pennsylvania, minds were quick to changed and the law was adopted.23

This was a terrible accident that had severe consequences. But the true lesson comes from paying attention to natural landscape and not ignoring signs of damage. By listening to experts such as engineers, architects, and geologists, who understand how the natural world works and the best disaster prevention, we can save lives and infrastructure.

- “South Fork Dam,” National Park Service, 21, January 2017, 12, November 2017, https://www.nps.gov/jofl/learn/historyculture/south-fork-dam.htm. ↵

- Walter Smoter Frank, “The Cause of the Johnstown Flood: A new look at the Historic Johnstown Flood of 1889,” Civil Engineering (1988), http://www.smoter.com/flooddam/johnstow.htm. ↵

- Walter Smoter Frank, “The Cause of the Johnstown Flood: A new look at the Historic Johnstown Flood of 1889,” Civil Engineering (1988), http://www.smoter.com/flooddam/johnstow.htm. ↵

- Walter Smoter Frank, “The Cause of the Johnstown Flood: A new look at the Historic Johnstown Flood of 1889,” Civil Engineering (1988), http://www.smoter.com/flooddam/johnstow.htm. ↵

- “South Fork Dam,” National Park Service, 21, January 2017, 12, November 2017, https://www.nps.gov/jofl/learn/historyculture/south-fork-dam.htm. ↵

- Walter Smoter Frank, “The Cause of the Johnstown Flood: A new look at the Historic Johnstown Flood of 1889,” Civil Engineering (1988), http://www.smoter.com/flooddam/johnstow.htm. ↵

- Walter Smoter Frank, “The Cause of the Johnstown Flood: A new look at the Historic Johnstown Flood of 1889,” Civil Engineering (1988), http://www.smoter.com/flooddam/johnstow.htm. ↵

- Walter Smoter Frank, “The Cause of the Johnstown Flood: A new look at the Historic Johnstown Flood of 1889,” Civil Engineering (1988), http://www.smoter.com/flooddam/johnstow.htm. ↵

- “1861-1945: Era of Industrial Ascendancy” phmc.state.pa.us, last modified August 26, 2015, http://www.phmc.state.pa.us/portal/communities/pa-history/1861-1945.html. ↵

- Walter Smoter Frank, “The Cause of the Johnstown Flood: A new look at the Historic Johnstown Flood of 1889,” Civil Engineering (1988), http://www.smoter.com/flooddam/johnstow.htm. ↵

- “South Fork Dam,” National Park Service, 21, January 2017, 12, November 2017, https://www.nps.gov/jofl/learn/historyculture/south-fork-dam.htm. ↵

- “South Fork Dam,” National Park Service, 21, January 2017, 12, November 2017, https://www.nps.gov/jofl/learn/historyculture/south-fork-dam.htm. ↵

- Walter Smoter Frank, “The Cause of the Johnstown Flood: A new look at the Historic Johnstown Flood of 1889,” Civil Engineering (1988), http://www.smoter.com/flooddam/johnstow.htm. ↵

- Encyclopedia Britannica, 2017, s.v. “Andrew Carnegie,” https://www.britannica.com/biography/Andrew-Carnegie. ↵

- Encyclopedia Britannica, 2017, s.v. “Andrew Carnegie,” https://www.britannica.com/biography/Andrew-Carnegie. ↵

- “South Fork Dam,” National Park Service, 21, January 2017, 12, November 2017, https://www.nps.gov/jofl/learn/historyculture/south-fork-dam.htm. ↵

- Edwin Hutcheson, Floods of Johnstown: 1889-1936-1977 (PA: Cambria County Tourist Council, 1989). ↵

- “South Fork Dam,” National Park Service, 21, January 2017, 12, November 2017, https://www.nps.gov/jofl/learn/historyculture/south-fork-dam.htm. ↵

- Edwin Hutcheson, Floods of Johnstown: 1889-1936-1977 (PA: Cambria County Tourist Council, 1989). ↵

- Walter Smoter Frank, “The Cause of the Johnstown Flood: A new look at the Historic Johnstown Flood of 1889,” Civil Engineering (1988), http://www.smoter.com/flooddam/johnstow.htm. ↵

- “The Johnstown Flood,” history.com, accessed November 9, 2017. http://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/the-johnstown-flood-2. ↵

- Jed Handelsman Shugerman, “The Floodgates of Strict Liability: Bursting Reservoirs and the Adoption of Fletcher v. Rylands in the Gilded Age,” The Yale Law Journal 110, no. 2 (2000): 335. ↵

- Jed Handelsman Shugerman, “The Floodgates of Strict Liability: Bursting Reservoirs and the Adoption of Fletcher v. Rylands in the Gilded Age,” The Yale Law Journal 110, no. 2 (2000): 335. ↵

Tags from the story

Johnstown Flood of 1889