April 18, 2021

The Louisiana Purchase: The Greatest Land Grab In History

During the rather warm first weeks of April in Paris in 1803, rumors were abound throughout Napoleon’s court in the Tuileries Palace. The rumors were of defeat in Saint-Domingue, increased aggression and hostilities with England that could lead to war, and a heightened concern of war in America over the Louisiana Territory.1 These were the conversations and gossips that were most often heard by the U.S. Ambassador to France, Mr. Robert Livingston. Livingston was charged originally as an ambassador to France with plans to discuss the territory of Louisiana. This was carried out as an attempt to establish and grow diplomatic relations with the expanding nation just two years prior. Despite his best efforts, Livingston had accomplished very little by this point in his tenure as Ambassador for the United States in France. However, this was soon to change.2 Mr. Livingston was soon to be on the negotiating side of the largest land purchase in history.

We begin our story in those same crowded halls of the Tuileries Palace in Paris, where Livingston spent countless hours trying to negotiate just the sale of the Port of New Orleans, and the two Floridas from the French. With the majority of the negotiations remaining stalled, due to the increased focus upon the rebellion in Saint-Domingue, Livingston’s efforts were almost all for naught. However, with the news of a crippling defeat at the hands of the rebelling slaves of Saint-Domingue, hope was slightly regained, as Napoleon was left with a difficult decision to make. He could either double down on his efforts in the Caribbean by sending more troops and further thin the military might of France against the slaughter. Or, he could cut his losses and hopefully make a slight profit from the foul up. In seeking the path of least resistance, Napoleon chose the latter. In doing so, he charged the French Treasury Minister François Barbe-Marbois, to formally report on and negotiate the sale of the entire Louisiana Territory with Livingston.3 However, this information was overheard and carried out in secret by the French Minister of Foreign Affairs, Charles Maurice de Talleyrand. Upon hearing this prematurely given news, the Ambassador by all accounts was taken aback by the shocking revelation. Furthermore, the bewildered Livingston nearly fumbled the entire negotiation process before it even began, by exclaiming, as he had once before to Joseph Bonaparte that, “The United States only intended to purchase the Port of New Orleans, the two Floridas, and perhaps the territories north of the Arkansas River from the French, not the entire territory.”4 However, after taking a few days to mull over the offer, Livingston returned to his senses and began to attend to the tedious cycle of negotiations. But how did the United States reach this pivotal opportunity for expansion in the first place? To better understand this scene, we must first take a step backwards in time to the original colonization and claiming of the Louisiana Territory by France in 1682, and examine its storied history up to this point.

The Louisiana Territory was originally claimed by France in 1682, by famed explorer Robert Cavalier de La Salle. It was named in honor of King Louis XIV, and remained in French control for much of the eighteenth century. However, the first disruptions of the French domain within the region began with the Seven Years War, which commenced in 1756 and continued on until 1763. At the end of this multinational conflict and as part of a treaty agreement, France ceded the entirety of the Louisiana Territory west of the Mississippi River to Spain, and the remainder of its land holdings in North America to Great Britain, with the Treaty of Paris in 1762.5 This transfer of land was, however, very short lived. With the rise of Napoleon in the following years, the power of the French military resurged. This resurgence of military might led to the ability for France to pressure King Charles IV of Spain (r. 1788-1808) in 1801 to cede back the Louisiana Territory for the Principality of Tuscany in Italy. This was under the agreement that France would not sell the Louisiana Territory to any other nation from that point forward.6 This, however, turned to not be carried out as the French and Spanish had originally agreed upon. It is important to mention, that up to this point, the Louisiana Territory had been consistently looked at as a backwater, with no real significant importance. Aside from an occasional exploration trip up the Mississippi River and throughout its numerous tributaries, no extensive research, mapping, or exploration had ever been carried out in the territory, thus allowing for the territory’s massive wealth in resources to remain hidden from view until the expeditions of Lewis and Clark that followed the Louisiana Purchase.7

In returning to the negotiations with Mr. Livingston and Mr. Talleyrand, with this additional historical background in hand, one can begin to see the significance of such a purchase for both nations. At this point, news had reached Livingston of James Monroe’s arrival in Paris. Feeling slighted by the instruction of James Monroe, and possibly even feeling replaceable, Livingston was none too pleased with Mr. Monroe’s arrival. Feelings of discontent aside, Livingston returned to the task at hand and continued his work on negotiating a good deal.8 By a shear chance of fate at a dinner that Mr. Livingston was holding in honor of Mr. Monroe’s arrival, Mr. Barbe-Marbois had showed up unannounced. In the fray of the dinner proceedings, Marbois was able to express the urgency of the purchase to Livingston, and was able to sweep him away to his offices at the Treasury. Unfortunately for Mr. Monroe and primarily due to a matter of pageantry and diplomacy, he had yet to make formal introductions with the foreign minister, and due to this fact, any form of negotiations on his behalf would seem to be uncouth. With a bit of luck to possibly claim all the credit for such a monumental purchase, Livingston whisked away to the treasury office to discuss terms of purchase with Mr. Marbois.9 But what significance would this purchase mean to the United States? What strategic importance would the Port of New Orleans bring to the relatively new nation, and what economic advantage would control of the Mississippi River create? To answer these questions, we can remove ourselves from the current steady going negotiations, to better examine the soon to be purchased Louisiana Territory as it pertains to American expansion.

The Louisiana Territory comprised not only the Port of New Orleans and the Mississippi River, but also consisted of nearly 827,987 square miles of unsettled lands.10 This additional territory would effectively double the size of the United States overnight. To provide a better scope of the size of this land, the territory stretched from the Gulf of Mexico to the modern day Canadian border, and then sprawled out westward toward the Rocky Mountains and upwards to the Pacific Northwest. This land encompassed the massive mineral hoards within the Black Hills of present-day North and South Dakota, along with thousands upon thousands of miles of great plains lands.11 This massive parcel of land would eventually become six entire states, and would consist of lands that helped shape nine additional states as well. This territory would allow for the complete control of the Mississippi River, and would act as the first major step towards doctrine of Manifest Destiny in the coming decades. Without the control of the Mississippi River and the lands around it, it can be easily argued that the United States would have never developed into the industrial powerhouse it became by the turn of the century.

Returning back once more to the negotiations at hand between Mr. Livingston and Mr. Marbois, it is beginning to dawn on the pair the significance of the negotiations that they are currently having. With Livingston recognizing that this purchase, albeit an incredible bargain, would require for the United States to withdrawal a loan to cover the cost. However, the incredible bargain being struck, land at nearly 2 to 39 cents per acre, equaling roughly fifteen million US dollars, could not be passed up. Marbois also faced some considerable facts, that this purchase would effectively end French imperial expansion within the Americas. With the loss of Saint-Domingue, the Louisiana Territory was effectively the last land holding France possessed within the North American Continent. With newly realized revelations about the work they were carrying out, the pair continued their due diligence hammering out the details of the purchase.12 But what truly led Napoleon to make such a bold decision with his land and territory? Was it truly just to buy ammunition and supplies for an impending war with England, or was there more to the picture? Let us pause once more to look at the events and ill-fated luck of Napoleon that led to the monumental decision to sell the Louisiana Territory.

At this point in Napoleon’s reign, the growing pains associated with a large empire had begun to set in. The Treaty of Amiens, signed in 1802, was a treaty that had temporarily ended the conflicts between the French and the United Kingdom, following the War of the Second Coalition. However, both sides were dragging their feet with complying with specific parts of the treaty. France was required to evacuate the Netherlands but had yet to comply, while Great Britain had yet to evacuate the Island of Malta within the Mediterranean.13 Due to the apparent posturing of both nations via non-compliance, tensions had increased dramatically and war was becoming an increasing possibility. In the Caribbean, Napoleon had lost an estimated thirty thousand troops thus far during the rebellion of Saint-Domingue (present day Haiti), and the conflict looked to spell defeat. With Saint-Domingue no longer within the French Domain, the need for the Louisiana Territory was not as dire. Furthermore, a war with the United States allied with Great Britain would not be an ideal situation for Napoleon. So, ammunition and supplies were part of the equation, yet other contributing factors certainly influenced Napoleon’s decision to sell the Louisiana Territory.

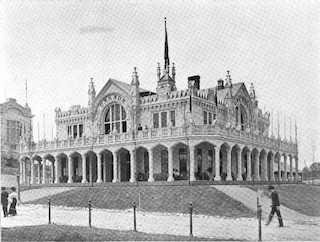

Returning one last time to the intense negotiations being carried out by Mr. Livingston and Mr. Marbois within the offices of the Treasury in Paris, a deal is soon to be struck. A sum of fifteen million U.S. dollars had been loosely agreed upon in exchange for roughly 828,000 square miles of land that included both the Port of New Orleans (a location that the U.S. would have gladly paid nearly ten million U.S. dollars for alone) and the lands surrounding the entire stretch of the Mississippi River.14 After returning to his home, Livingston reconvened with Monroe and went forth to further hammer out the terms. This day was April, 13, 1803. The deliberations between Mr. Marbois, Mr. Livingston, and Mr. Monroe carried out for an additional eighteen long and arduous days, with offers and counteroffers being ferried back and forth between both sides. It wasn’t until May 2, 1803 that the Treaty with France was formally signed by all parties, and even then, the deal was still rather precarious.15 One could argue that this signing of the Treaty with France was what doubled the land size of the United States overnight; however, one could also make a valid argument that it wasn’t until the hoisting of the colors over New Orleans that the deal was officially completed. This momentous ceremony actually did not take place until nearly a full year after the treaty was signed. The ceremonial hoisting of the colors took place in New Orleans on March 10, 1804 in what is now known as Jackson Square.16

In closing, the Louisiana Purchase still stands today as the largest single land sale in history. In spite of just recapping the events that transpired to make such a purchase possible, it is still difficult to fathom the enormity of such a large and predominantly non-violent land transfer between two world powers. The events leading up to and immediately after the purchase could not have gone differently or perhaps a different result might have occurred. In all respects, many historians could easily argue that had Napoleon realized the value of the Louisiana Territory and refused to sell it, the development of the United States would have been vastly different. It can also be easily argued that had the United States not held total control of the Mississippi River during the years leading up to the Industrial Revolution, the United States would not have emerged as an economic powerhouse at the turn of the century. With that said, the importance of the Louisiana Purchase should be self-evident and abundantly plan to see: the single purchase that ultimately doubled the size of a young, vibrant, and diverse nation overnight.17

- Thomas J Fleming, The Louisiana Purchase (Hoboken: Turning Points, 2003), 108,109. ↵

- Thomas J Fleming, The Louisiana Purchase (Hoboken: Turning Points, 2003), 22, 23. ↵

- Encyclopedia Britannica, s.v. “Louisiana Purchase.” ↵

- Thomas J Fleming, The Louisiana Purchase (Hoboken: Turning Points, 2003), 93. ↵

- Encyclopedia Britannica, s.v. “Louisiana Purchase.” ↵

- Encyclopedia Britannica, s.v. “Louisiana Purchase.” ↵

- Encyclopedia Britannica, s.v. “Louisiana Purchase.” ↵

- Thomas J Fleming, The Louisiana Purchase (Hoboken: Turning Points, 2003), 99, 100. ↵

- Thomas J Fleming, The Louisiana Purchase (Hoboken: Turning Points, 2003), 115, 116. ↵

- Sanford Levinson, and Bartholomew Sparrow, The Louisiana Purchase and American Expansion, 1803-1898 (Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2005), 69. ↵

- Sanford Levinson, and Bartholomew Sparrow, The Louisiana Purchase and American Expansion, 1803-1898 (Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2005), 69-71. ↵

- Thomas J Fleming, The Louisiana Purchase (Hoboken: Turning Points, 2003), 115-117. ↵

- Thomas J Fleming, The Louisiana Purchase (Hoboken: Turning Points, 2003), 100. ↵

- Thomas J Fleming, The Louisiana Purchase (Hoboken: Turning Points, 2003),117. ↵

- Thomas J Fleming, The Louisiana Purchase (Hoboken: Turning Points, 2003), 117-129. ↵

- Encyclopedia Britannica, s.v. “Louisiana Purchase.” ↵

- Encyclopedia Britannica, s.v. “Louisiana Purchase.” ↵

Tags from the story

François Barbe-Marbois

James Monroe

Louisiana Purchase

Mississippi River

Napoleon Bonaparte

New Orleans

Robert Livingston