February 19, 2018

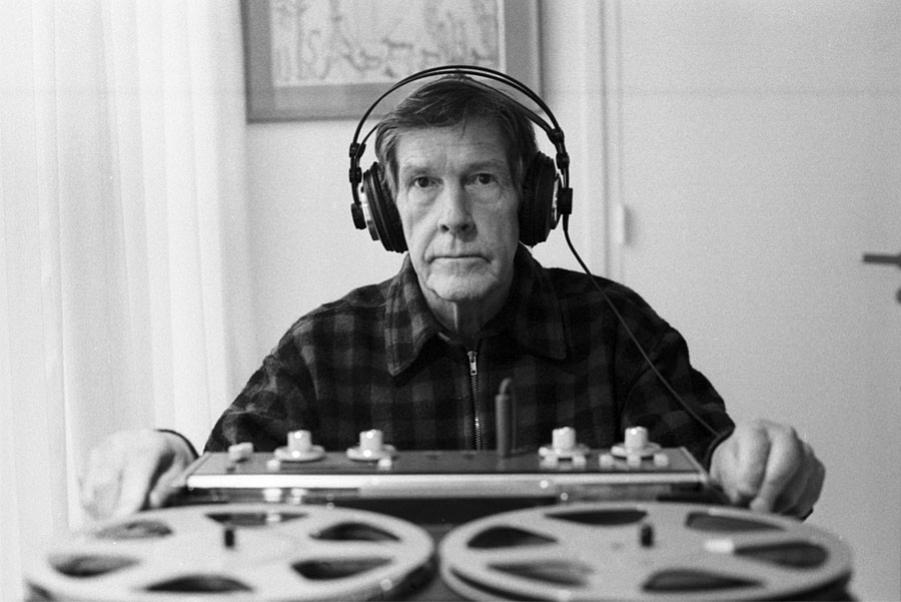

The Pioneer of 20th Century Music: John Cage

“[John Cage was] not a composer, but an inventor – of genius.” –Arnold Schoenberg1

When one thinks of nineteenth-century music, it is often seen as a time of smooth and contemporary classical music. This time period was one of great musical classicism, often performed in opera halls, churches, and concert halls. Often referred to as the Romantic Period, the music prior to the twentieth century was of specific form and structure, typically never straying from the Classical period’s styles. However, beginning in the twentieth century, there were great musical innovations and changes. With varying forms, genres, rhythms, and much more, the music of this era was simply profound. The twentieth century can be described as a time of both growth and experimentation in music. With its wide availability, varied forms, and dramatic innovations, music was developing and changing like never before.2

Now imagine sitting at an orchestral concert. The sounds of contemporary classical music fill your ears as the crowd sits in amazement at the beauty of the harmonious sounds produced by the musicians—this is a traditional nineteenth-century concert experience. Now picture this: you are sitting in a concert hall watching all of the performers enter the stage, and you wait in anticipation for them to pick up their instruments and play…but they never do. They simply sit and stare at their sheet music, leaving the entire room silent. This is a concert composed by twentieth-century composer John Cage. Cage was perhaps one of the most influential composers of this era. His unconventional ideas and out-of-the-box elements made him a pioneer in his lifetime—one that was revolutionary.

Cage was born September 5, 1912 in Los Angeles, California. In his early childhood, he was introduced to music by various relatives. Once he reached the fourth grade, his aunt exposed him to nineteenth-century classical music, thus inspiring him to receive his first piano lessons at the age of ten. Later in his life, he dabbled in everything from architecture to poetry—soon trying his hand at music and theater. After deciding to pursue music, Cage began sending his compositions to Henry Cowell (a famous American composer), who in return suggested that he learn from Adolph Weiss (another famous American composer), and then take lessons from Arnold Schoenberg—the prominent Austrian composer and music theorist. Following Cowell’s advice precisely, Cage went on to study under Schoenberg at multiple college institutions, soon developing his own creative genius. And although Cage pursued many jobs at this point in his life, including occupations such as being a lecturer, a wall washer, a dance accompanist, and a composer, it was in the arts that he thrived the most. Cage was able to brew radical innovations within music that left a lasting impact.3

Cage contributed much to the scope of twentieth-century music. He not only experimented with the modern understanding of structure and arrangement, but also with instrumentation, often using unorthodox instruments like household items or metal sheets. His use of these items allowed for an amplified understanding that, truly, anything can be music. The ‘noise’ he created held lasting impacts on modern musical compositions. Cage also had a strong interest in electronics and how it could contribute to music. He experimented with microphones, volume, feedback, computers, and much more to manipulate sounds. Additionally, he is also credited with creating, and extensively using, the prepared piano. This instrument is a piano with altered sound due to objects being placed on or between the strings. Its minimalist sound was intended to further “expand the bounds” of seemingly perfect musical instruments. In fact, after its invention, Cage was given a grant to explore music in his own, deeper way.4 This instrument alone contributed much to the scope of twentieth-century dance music. In addition to these great musical innovations, he is best known for developing the percussion orchestra and the happening, which is the clashing of discordant musical sounds.5

In 1950, Cage produced what was perhaps his most infamous innovation—aleatoric music, or music of chance. This is when a portion of the music is left up to chance; simply, the course of the music is determined by the performer and their creative ways, commonly referred to as indeterminancy in music. Cage is most famous for his concert pieces and dance-related works. His influence stemmed from both Indian and Asian concepts, which he pursued after a period of disillusionment in his own compositions; he did so by turning to Zen Buddhism and an Indian musician named Gita Sarabhai, whom he tutored. It was through these influences that Cage developed the concept of indeterminism and randomness within music—spurring one of the most inventive aspects of composition in the twentieth century. Chance operations were a drastic shift in the form and structure of composition, but this exotic idea allowed performers to become more expressive in their own way. Aleatoric music was created after Cage noticed that traditional music scores were too abstract and old-fashioned; he viewed music as much more concrete and literal.6 The effect of aleatoric music was astounding—no single performance was the same, and each individual performer had the freedom to create their own art. Cage’s techniques in music of chance led to much growth within pop and rock genres, two of the most popular musical categories today. By simply doing away with traditional score sheets and predetermined music, he accessed a wider world—one where ‘noise’ was much more than an everyday occurrence; it was art.

Unfortunately, Cage’s aleatoric music was not a success when performed in concert. It was even recorded that during a performance of his work at Town Hall in New York City, 1958, the audience loudly booed and hissed at his compositions, ultimately dissatisfied with the improvisations Cage incorporated. Musicologists regarded his work with the utmost suspicion; this is reflected in the fact that there are only a handful of dissertations on Cage during his peak time period.7 Despite the hate he received, he continued on to his next big creation, in hopes it would have a greater response.

Cage was a composer that saw the world differently than anyone else during this time period. His emphasis on silence was yet another note-worthy innovation that later led to his prominence as a composer. Inspired by minimalism, which consists of few musical components, Cage had a profound appreciation for the idea of everything around us being seen as music. The end result of this insane idea was the popular work 4’33”, which is a three-movement work made for any combination of instruments, but it is a piece in which all performers remain silent for that amount of time.8 To Cage, it was important that one get out of the music, otherwise they would get lost within it. The openness of silence allowed listeners the freedom to focus, or unfocus, on whatever they pleased while also accepting any unintentional sounds occurring in a performance.

When performed in concert, it was a bit awkward to watch. Every performer would sit still for precisely four minutes and thirty-three seconds, not once touching their instruments. The silence of this piece is meant to emphasize the sounds of the surrounding environment—even if that might mean listening to the coughs, shuffling, and whispering of the audience; and that’s exactly what it was.9 Critics had a love-hate relationship with this concert. Not only did the silence speak volumes, but it didn’t speak at all.

Though there were few critics who praised Cage’s inventive ways, a majority of the public was furious at the ‘noise’ that he had the audacity to refer to as music. He was too often viewed not as a composer, but as a misled writer who lacked an understanding of basic musical ideas.10 His seemingly misunderstood approach led many to see him as fundamentally different, his ways unconventional. The avant-garde style he followed was repeatedly criticized because of the mere fact that it was not what people were used to hearing. Cage was nothing more than a tradition-changing outsider that destroyed music more and more with each composition.11 Cage’s unique contributions are ones that revolutionized music in the twentieth century. Through his unique style, he influenced upcoming composers such as Philip Glass, La Monte Young, and Steve Reich, all who were enchanted with the idea of a non-traditional way of thinking. In addition, he influenced bands such as Radiohead and Stereolab. In his later career, Cage received an award from The National Academy of Arts and Letters, was given a Guggenheim Fellowship, and earned a doctoral degree in performing arts.12

Cage received more hate than love in the crazy world of music. His innovations were controversial, but they never stopped him from pursuing his passion. Nonetheless, in 1961, he began writing and publishing books, his first and most famous being Silence, which was a collection of essays, lectures, and scores. This, combined with the publishing of his scores, led to a much higher prominence for Cage than ever before. In addition, his silent concert gained prominence as it was performed in concert halls all over the country—his persistence was the key to his success. Despite the never-ending hate, he flourished amid the controversy. This is because, to him, anything and everything we do qualifies as music. It was not until after his death in 1992 that a large number of essay tributes were published on Cage’s influence and creative genius.13 He was proud to push boundaries, no matter how much it annoyed audiences.14

Through critique and hate, Cage still pursued his inventive ideas. Going on to publish multiple books, one famous composition by Cage is Sonatas and Interludes, which is a collection of twenty pieces made for prepared piano and is seen as one of his greatest works; it was even performed at Carnegie Hall in 1949. Some famous performers of his work include Margaret Leng Tan, David Tudor, and Stephen Drury.15

Still today, his ideas of music of chance and extended silence continue to dominate the background of songs we enjoy. Through his music, Cage attempted to break away from the traditional standards of harmony, patterns, and rhythmic structure. John Cage was more than a composer—he was an innovator. He not only experimented with a multitude of musical ideas, but he challenged the very idea of music. His work opened the door to many new ideas, paving a new path in twentieth-century music.16

- Encyclopedia of World Biography, 2004, s.v. “John Cage.” ↵

- The History of Classical Music, 2013, s.v. “The Musical Art of the Modern Era,” by Kallen A. Stuart. ↵

- Encyclopedia of World Biography, 2004, s.v. “John Cage.” ↵

- Encyclopedia of World Biography,2004, s.v. “John Cage.” ↵

- Encyclopedia of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgendered History in America, 2004, s.v. “Cage, John,” by William Pencak. ↵

- Braden Wayne Joseph, Experimentations : John Cage in Music, Art, and Architecture (New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2016), 35. ↵

- Sara Haefeil, John Cage : A Research and Information Guide (New York: Routledge, 2018), 7. ↵

- The History of Classical Music, 2013, s.v. “The Musical Art of the Modern Era,” by Kallen A. Stuart. ↵

- The History of Classical Music, 2013, s.v. “The Musical Art of the Modern Era,” by Kallen A. Stuart. ↵

- Sara Haefeil, John Cage: A Research and Information Guide (New York: Routledge, 2018), 5. ↵

- Sara Haefeil, John Cage: A Research and Information Guide (New York: Routledge, 2018), 6. ↵

- The Art Story, 2017, s.v. “John Cage Artist Overview and Analysis,” by Justin Wolf. ↵

- Sara Haefeil, John Cage: A Research and Information Guide (New York: Routledge, 2018), 8. ↵

- The History of Classical Music, 2013, s.v. “The Musical Art of the Modern Era,” by Kallen A. Stuart. ↵

- The Art Story, 2017, s.v. “John Cage Artist Overview and Analysis,” by Justin Wolf. ↵

- Baker’s Biographical Dictionary of Musicians, 2001, s.v. “Cage, John (Milton Jr.),” by Nicolas Slonimsky, Laura Kuhn, and Dennis McIntire. ↵

Tags from the story

composer

John Cage

Kimberly Simmons

I am a double degree student majoring in Marketing and Communications with a minor in Math at St. Mary’s University in San Antonio, TX. My passion lies in spreading honest, effective messages, serving those in need, and advocating for social justice. I enjoy reading, baking, and spending free time with my family!

Author Portfolio Page