October 21, 2018

The SCUM Manifesto

Valerie Solanas had a very troubled childhood. When she was young, she was molested by her father, and soon after, her parents divorced. Once she was older, she constantly moved from home to home. As a young adult, her life did not get any easier. She had a son out of wedlock, and gave him up for adoption; before long, she turned to prostitution in order to support herself. Solanas managed to get a college education and shortly after attaining a psychology degree, she began to develop her idea that “women are biologically superior to men.”1

In 1967, Valerie Solanas self-published her SCUM Manifesto, which stood for the Society for Cutting Up Men. She was able to compose her manifesto by using the money she earned from prostitution to rent a hotel room for days at a time. Her manifesto called for the destruction of men, and blamed them for the problems ravaging our world. The manifesto called for women to come together as “SCUM,” which she described as “dominant, secure, self-confident, nasty, violent, selfish, independent, proud, thrill-seeking, free-wheeling, arrogant females, who consider themselves fit to rule the universe.”2 As for men, the manifesto demanded that they acknowledge their unfitness for power and advocate for their own destruction. Solanas first distributed her manifesto in the streets of New York. And there was quite a mixed response. Some people did not know whether to take the manifesto seriously, while others saw intelligence in Solanas because of it.3 Along with her SCUM Manifesto, Solanas also wrote a play called Up Your Ass. This play follows a day in the life of a prostitute. It details interaction with everyone from a pair of drag queens to a matron. The play also severely criticizes the dynamics of male and female power.4 Solanas was proud of her play and wanted to see it produced, which was when Andy Warhol came into the picture.

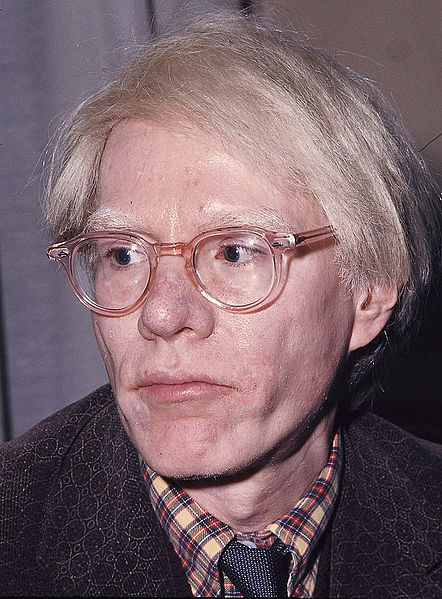

When we hear the name Andy Warhol, fame, pop art, and images of Campbell Soup cans come to mind, but we do not realize the hardships that are also accompanied with this name. Similar to Solanas, Warhol had his share of setbacks while growing up. Warhol’s childhood was marked by crushing poverty during the Great Depression. While his father was away as a laborer, he went door to door with his mother selling handmade flowers in discarded tin cans. His talent soon became apparent and by the age of twelve he had learned to retouch his brother’s photographs. Years later, after receiving B.F.A. degree from Carnegie Mellon University, he permanently moved to New York.5 Unlike Solanas, his life took a turn for the better. In the 1950’s, Warhol gained some standing as a commercial artist. He was hired as chief illustrator for Miller Shoes, and his popularity began to take off. Slowly, his work became more and more well known, and he won several design awards.6 Warhol gained fame through his outrageous behavior and innovative art. His outrageous behavior included such things as painting a self portrait picking his nose, titled The Broad Gave Me My Face, but I Can Pick My Own Nose. He submitted the piece in an exhibit during his senior year of college, but it was rejected.7 The innovative art refers to works of art like his Campbell’s Soup Can that related to the technological world and represented common scenes. Warhol would come to be known as one of the most influential artists of the twentieth century, and his work became symbolic of Pop Art, and his story as one of rags-to-riches.8

Eventually, Valerie Solanas began to associate herself with Warhol’s circle of friends and The Factory, which was a large studio loft that served as a studio and party room. This place attracted celebrities and “near celebrities” who took part in theatrics of various kinds, and soon became a center for pop culture, which attracted a variety of “glamorous people.”9 Solanas appeared in two of Warhol’s films, I, a Man, and Bike Boy. Solanas also hoped that Warhol would help promote her writing. She gave Warhol a copy of her play, Up Your Ass, but he thought the play was too obscene, and ended up misplacing it.10

Solanas did, however, receive attention from Maurice Girodias of Olympia Press, who contracted with her to publish her manifesto. As time went on, Solanas grew worried about their contract and believed that Girodias had tricked her into signing over the rights to her written work. Solanas felt that her intellectual property had been rejected and threatened, and so she decided to take matters into her own hands. She armed herself with two guns and went in search of Girodias.11

On the morning of June 3, 1968, Solanas waited for Girodias at his hotel, but he did not return. Armed with two pistols she decided to look for him at Warhol’s studio. This is where she encountered Warhol and another writer, Mario Amayo. Solanas was angered that he had disregarded her play, and even thought that he may be trying to take credit for it. At 4:15 P.M. Solanas shot Warhol three times. The first gun shot was followed by chaos and confusion. Once Warhol realized what was happening he screamed, “No! No! Valerie! Don’t do it!” but she fired a second time.12 Warhol fell to the ground and tried crawling under the desk. Solanas followed him and fired a third time. This bullet entered Andy’s right side and exited the left side of his back. He recalled feeling as though a firecracker had exploded inside him, which was followed by screams. Valerie believed she had killed Warhol and moved on to her next target, Mario Amayo. She stood over him and fired her fourth shot, but she missed him. As he watched her aim again, Amayo whispered a prayer, after which Solanas shot again. This time she hit her target and he was injured above his hip, but the bullet missed his organs. He was able to stumble to his feet and past double doors that he held shut.13 Solanas believed that they were locked, so she went in search of another victim. She got to another Factory member, who pleaded with Solanas to leave while she still could. Surprisingly, Solanas listened, and she bolted to the elevator and escaped, leaving behind a trail of pain and chaos.

Warhol was rushed to the hospital where he was given a 50/50 chance of survival. He was pronounced clinically dead when he arrived, and his surgical team was astounded at the amount of damage the bullet had done to the interior of his chest.14 The bullet had entered the right side, passed through his lung, ricocheted through his esophagus, gall bladder, liver, spleen, and intestines, before exiting his left side leaving a large hole. Warhol was in surgery for five and a half hours, after which he survived. On June 13, he was still in intensive care and on the critical list, but doctors reported that he was on his way to recovery.15 Almost four hours later, at 8:00 P.M., Solanas turned herself in to a policeman in Times Square and confessed that she had shot Warhol because he had too much control over her life.16

On June 13 1968, Solanas appeared in court, defended by feminist attorney Florynce Kennedy. It was determined that Solanas was unfit to stand trial and was diagnosed as a paranoid schizophrenic. A year later, she pleaded guilty to first-degree assault and received a sentence of three years’ imprisonment, which included the year she had already spent in psychiatric confinement.17 After her release, Solanas spent most of her time living in New York, mostly homeless. She relocated to San Francisco several years later, where she began to work on a new manuscript, but died before it was ever completed. When her body was discovered, conditions suggested that she had been dead for days. It was also found that she died of bronchopneumonia, which is an inflammation of the lungs.18

Valerie Solanas craved the approval of Warhol, and to leave an imprint in feminism. Instead, however, Solanas is remembered as the woman who shot Andy Warhol. After the shooting, only a few woman came to her defense; most feminists did not support her ideas. In 1987, a film was produces titled I Shot Warhol that brought Solanas back from obscurity. Even that film, however, did not bring the type of recognition she had so desperately craved.

- Salem Press Biographical Encyclopedia, 2013, s.v. “Valerie Solanas,” by Francesca Gamber. ↵

- Thomas Riggs, The Manifesto in Literature (Detroit: St. James Press, 2013), 123. ↵

- Thomas Riggs, The Manifesto in Literature (Detroit: St. James Press, 2013), 123-125. ↵

- Andi Zeister, “Up Your Ass,” Bitch Magazine: Feminist Response to Pop Culture, Winter 2008. ↵

- The Scribner Encyclopedia of American Lives, 1999, s.v. “Warhol, Andy.” ↵

- Salem Press Biographical Encyclopedia, 2016, s.v. “Andy Warhol,” by Harry J. Eisenma. ↵

- The Scribner Encyclopedia of American Lives, 1999, s.v. “Warhol, Andy.” ↵

- Salem Press Biographical Encyclopedia, 2016, s.v. “Andy Warhol,” by Harry J. Eisenma. ↵

- Salem Press Biographical Encyclopedia, 2016, s.v. “Andy Warhol,” by Harry J.Eisenma. ↵

- Andi Zeister, “Up Your Ass,” Bitch Magazine: Feminist Response to Pop Culture, Winter 2008. ↵

- Encyclopedia of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgendered History of America, 2004, s.v. “Solanas, Valerie.” ↵

- Victor Brokis, Warhol: The Biography (Massachusetts: De Capo Press, 2009), 298. ↵

- Victor Brokis, Warhol: The Biography (Massachusetts: De Capo Press, 2009), 298-299. ↵

- Richard F. Shepard, “Warhol Gravely Wounded In Studio; Actress Is Held: Woman Says She Shot Artist, Who Is Given a 50-50 Chance to Live,” New York Times, June 1968, https://search.proquest.com/. ↵

- Victor Brokis, Warhol: The Biography (Massachusetts: De Capo Press, 2009), 303. ↵

- Richard F. Shepard, “Warhol Gravely Wounded In Studio; Actress Is Held: Woman Says She Shot Artist, Who Is Given a 50-50 Chance to Live,” New York Times, June 1968, https://search.proquest.com/. ↵

- Encyclopedia of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgendered History of America, 2004, s.v. “Solanas, Valerie.” ↵

- Salem Press Biographical Encyclopedia, 2013, s.v. “Valerie Solanas,” by Francesca Gamber. ↵

Tags from the story

Andy Warhol

The Year 1968

Valerie Solanas