March 22, 2017

Black Codes, Jim Crow, and Social Control in the South

The American Story is not an easy one to tell. As Americans, we have superb war stories, we have stories of major sporting events, and we have the stories that will haunt us forever. I speak of course of the treatment of African Americans during times of civil unrest in the United States of America.

The South, post Civil War, was filled with uncertainty. After the additions of the thirteenth, fourteenth, and fifteenth amendments, African Americans were given basic civil rights equal to their fellow white Americans. There seemed to be an extreme power shift. No longer were they slaves. As much as this would seems like progress, when we look deeper and analyze the situation, we notice that this was perhaps just a shimmy forward.

During a brief time known as Presidential Reconstruction, the South was allowed to go back to their old ways of bigotry. One of their first attempts was the creation of a new set of anti-freedmen laws known as the Black Codes. These Black Codes were an early attempt at being able to control the lives of the newly freed African American population in the South. Though these laws did grant some basic rights, such as the right to marry and land ownership, they refused certain rights like the right to testify against a white person in court, the right to serve in state militias, and (before the ratification of the fifteenth amendment) the right to vote.1

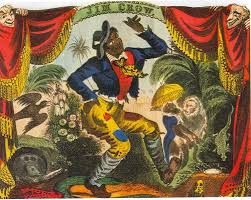

These Black Codes faced a temporary setback in the years 1867-1877, a period now known as Radical Reconstruction, where northern Republican politicians attempted to force the former Confederate States to integrate their Freedmen populations into Southern society. In 1877, those earlier Black Codes found new life with an even harsher set of laws. The Black Codes gave way to a new wave of discrimination called the Jim Crow Laws, named after a fictional character who misrepresented African-Americans as unintelligent human beings.2 These Jim Crow Laws hit African Americans in all places. For voting, most southern states placed poll taxes and literacy tests that didn’t explicitly disadvantage African Americans, but ended up doing so. A more direct attack was the segregation of almost everything. Pools, water fountains, restrooms, movie theaters, and even park benches were labeled as White Only or Colored Only. There were major consequences for ignoring or violating these laws.3 The new set of Jim Crow laws were legitimized by none other than the Supreme Court. In 1896, the decision of Plessy vs. Ferguson, the Supreme Court case based on a similar event to that of Rosa Parks years later, declared that the “Separate, but Equal” clauses that some states used, such as Louisiana, did not violate the Fourteenth Amendment. After the seven to one vote passed, Southern politicians began to double down and become harsher now that law was fully on their side.4

But these legal forms of social control were reinforced by a number of extra-legal forms, namely lynching. Lynching is a form of vigilante justice where extralegal means are used on individuals by taking the law into one’s own hands to inflict physical punishment or even death upon another person.5

Until 1850, most acts of lynching in the United States were non-lethal.5 During the American Revolutionary War, patriots would seize and destroy any opposing loyalist’s shop and burn it to the ground or seize the persons themselves and proceed to tar and feather them. The use of lynching was just a form of intimidation. Even before the Civil War, lynchings of African Americans were physical beat downs, but rarely was someone killed. The modern sense of lynching wasn’t used until the eve of the Civil War as Southerners began to use such methods to put down slave insurrections. After the Civil War, lynching evolved into the lethal forms of torture, burning, shootings, and, most notably, hanging.

According to the Tuskegee Institute, from the year 1882 to 1968 there were 4,743 lynchings reported across the United States, where 3, 446 or 73% of those lynched were African Americans.7 The most important thing to note from these statistics is that those lynched were people, not merely numbers on a page.

One notable lynching story is that of the young Emmett Till in 1955. Emmett Till was a fourteen year old boy from Chicago, Illinois who decided to go on a trip to Mississippi to visit some of his family.8 A fact that we know now is that over five hundred and eighty-one people were lynched in Mississippi, the highest of any other state in the Union.9 In a documentary titled “The Murder of Emmett Till,” Mamie Till, Emmett’s mother, warned him:

“… Mississippi is not Chicago. And when you go to Mississippi, you’re living by an entirely different set of rules. Ah, it is, ‘yes, ma’am’ and ‘no, ma’am’, ‘yes, sir’ and ‘no, sir’… And, Beau, if you see a white woman coming down the street, you get off the sidewalk and drop your head. Don’t even look at her.”10

Though she explained that she was exaggerating, what she feared for her son was what sadly occurred. While in Mississippi, Till–along with some cousins and friends–entered a shop run by Carolyn Bryant, a white woman. Reports vary about the specifics, but according to Bryant, Till made inappropriate remarks, whistled at her, and even said “Bye, Baby” as he left. After telling her husband, Roy Bryant, of the situation with Till in the store, Bryant and his brother-in-law J.W. Milam left in anger. The two abducted Till in the night from his relative’s home, beat him senseless and shot Till. They then tied pieces of metal to his body and threw the fourteen-year-old boy into the Tallahatchie River.11

Three days passed before the body was found by young boys fishing in the river. Roy Bryant and J.W. Milam were acquitted of their crime.12 The injustice of this crime soon shot all around the country. Though most African Americans saw the passing of Brown vs. Board of Education in 1954, which declared that separate but equal was unconstitutional, as a major step forward, people began to look farther and see that the United States still had a long way to go for equality.

The murder of Emmett Till was the true catalyst of the Civil Rights Movement. At the funeral for the young Till, his mother invited a photographer for Jet Magazine, a magazine for African Americans. The picture taken, to the right, was published and people everywhere were now able to see this monstrous act. Rosa Parks, the brave woman who most historians give credit for the beginning of the Civil Rights Movement, claimed that her knowledge of Emmett Till’s death and along with others, was one of the reasons for why she stood her ground on that bus in December of 1955.13

It would take many more years and many arrests for yet many more murders until the African American community felt safe from this type of vigilante violence. After Till, boycotts and marches become prominent in the South. One Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. began to rise from the ashes of the earlier lynchings and began to use his voice to speak out against these lynchings and violence, and lead against all the negative things that African Americans faced in the South. The NAACP (National Association for Advancement of Colored People) and other freedom fighting organizations partnered up and began to protest for African Americans rights. In 1957, the Civil Rights Act of 1957 was passed, yet this didn’t advance the lives of African Americans as much as it should have. More marches and people lost to senseless violence brought more civil rights acts such as the Civil Rights Acts of 1960, 1964, 1968, and 1991.14

History will go on, as historians it is our duty to record these brutal events and write down these statistics. As we write down these numbers and put our pens to paper and report, we must not forget that those lost are not just letters lost in a book or numbers typed into neat little columns. These people are the true victims and we must not forget. Learn your history, and know your truth.

- Eric Foner, Give Me Liberty!: An American History. Volume 2 (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2016), 180. ↵

- Salem Press Biographical Encyclopedia, January 21016, s.v. “Jim Crow in the U.S South,” by David M. Brown. ↵

- Salem Press Biographical Encyclopedia, January 2016, s.v. “Jim Crow Laws,” by William Moore. ↵

- Salem Press Biographical Encyclopedia, September 2015, s.v. “Separate, but Equal Doctrine and the Supreme Court,” by Pamela Haldeman. ↵

- Salem Press Biographical Encyclopedia, December 2015, s.v. “Lynching,” by Darryl Paulson. ↵

- Salem Press Biographical Encyclopedia, December 2015, s.v. “Lynching,” by Darryl Paulson. ↵

- “Lynching Statistics,” Journal of the American Institute of Criminal Law and Criminology 9, no. 1 (1973): 144–46. ↵

- Salem Press Biographical Encyclopedia, January 2016, s.v. “Emmett Till,” by Catherine R. Squires. ↵

- “Lynching Statistics,” Journal of the American Institute of Criminal Law and Criminology 9, no. 1 (1973): 144–46. ↵

- The Murder of Emmett Till, directed by Stacey Nelson (Arlington: PBS, 2003). ↵

- The Murder of Emmett Till, directed by Stacey Nelson (Arlington: PBS, 2003). ↵

- Salem Press Biographical Encyclopedia, January 2016, s.v “Emmett Till,” by Catherine R. Squires. ↵

- Eyes on the Prize , directed by Madison Davis Lacy, Jr. (Mississippi: PBS, 2006). ↵

- Salem Press Biographical Encyclopedia, March 2016, s.v. “Civil Rights Movement in the 1950’s,” by Carl Bankston. ↵

Tags from the story

Black Codes

Civil Rights Movement

Emmett Till

Jim Crow

Lynching

Murder

South