March 30, 2018

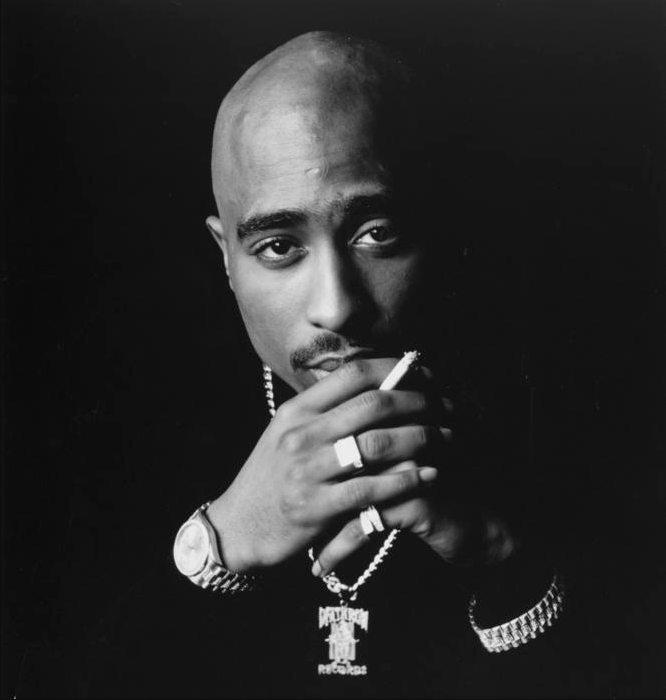

Tupac Shakur: “All Eyez on Me”

Tupac Shakur, a rapper in the 1990s, was known as a legend in the hip-hop and R&B industry for creating impactful music that told a story.1 Every single song he wrote was focused on social and cultural issues, such as gang violence, drugs, childhood struggles, and loss of loved ones, which is why he was successful from the beginning of his music career. Although he was successful, he had a lot of challenges that came with his lifestyle, including run-ins with the law for battery and sexual assault. He had a code that he honored so much that he even had it tattooed across his pelvis: “Thug Life.” This code, along with the hard life he lived, didn’t bring much ease to his situation with the law.2 Although Tupac had his troubles, his music was his escape and his motivation to overcome the obstacles that were set for him.

The first album Tupac released on his own was 2 Pacalypse Now in November of 1991.3 It was a hit from the start, reaching the top of the Billboard charts, and it didn’t take long for it to go gold, making this album his first solo debut as a rapper. He knew what he wanted and he was going to get to the top no matter what. In an interview with Vibe, he stated, “I never went to bed. I was working it like a job. That was my number one thing when I first got in the business. Everybody’s gonna know me.”4 However, with the start of his stardom and fame in music began the start of his journey living the “Thug Life.” He was constantly asked why he chose that lifestyle and why he chose to be a “thug.” His response was, “Because if I don’t, I’ll lose everything I have. Who else is going to love me but the thugs?”5

His music and his lifestyle attracted a lot of attention: good attention as well as bad. The good attention focused on the stories that were told by his music, stories that people could relate to as well as stories that other people couldn’t bring themselves to talk about. The bad attention came from authority figures who thought his music was undermining them and promoting violence among young adults listening to his music. One song that was criticized was “Brenda’s Got a Baby,” which listeners and authority figures thought contained too many explicit lyrics, overshadowing listeners’ judgment and interpretation of the song. In fact, the song was based on a newspaper article about a man who impregnated his cousin Brenda, whose name appears in the title of the song. She was only twelve years old and she tried to get rid of the baby girl by throwing her in a trash can. The song raised objections from the public because of the way it seemed to condone and praise the actions of Brenda.6 Most of Tupac’s songs were inspired by incidents in his life that turned into musical hits. This is how talented he was. He used his own struggles and the struggles of other people, turning them into songs that people could relate to.

Sadly, several days after Tupac released his second album Strictly 4 My N.I.G.G.A.Z in 1993, he was arrested on a sexual assault charge of a teenage girl in New York.7 The young girl was attacked in the Manhattan hotel where Tupac was staying. The girl that he allegedly raped had been previously in a romantic relationship with Tupac. She accused Tupac and three of his friends of abuse, and this was his first major run-in with the law. Most of the charges were dropped, except for the sexual assault charge. He was released on bond and later sentenced to a year and a half to four years in prison. Tupac served his sentence in New York’s Riker’s Island Penitentiary.8

Some people believed that this would be the last they would see or hear of Tupac. Little did they know that this would be his moment to shine. While incarcerated, Tupac decided to put his “Thug Life” behind him by saying, “If Thug Life is real, then let somebody else represent it because I’m tired of it. I represented it too much.”9 This turning point in his life wasn’t the only good thing that happened to Tupac while he was locked up. During this time, his third album, Me Against the World, which was released in 1995, started moving up the charts and ended up at number one. This album wasn’t like the others; it captured a new side of Tupac, portraying his poetic side, and showing the compassion and gratitude he had towards life.10 Not only was the album a hit, but his song “Dear Mama” reached top ten on the singles charts.11 The song was dedicated to his mother, Afeni Shakur. It was a very touching song that told the story of how Tupac grew up, as well as the sacrifices his mother made for him in the absence of his father. He also talked about how he turned to the streets, to drugs, and to violence to fill the void left behind by the absence of his father.12

After Tupac served eight months of his sentence, Suge Knight from Death Row Records paid a $1.4 million dollar bond to have Tupac released from prison. As soon as he was released, he was flown to Los Angeles to sign a contract with Death Row Records.13 However, signing with Death Row made his vow to change his lifestyle difficult for him. He was caught in the feud between the East Coast and the West Coast. This feud was mainly between the record labels Death Row and Bad Boys. The feud contained a lot of taunting and talking bad about each other through songs. It was their way of proving which record label was better at the time. They used personal vendettas to get to one another through song by exploiting personal facts about each other’s lives. There was a lot of going back and forth, as well as the occasional scuffles they’d get into when they would see each other in person.14

After signing with Death Row Records, Tupac released his first double album, All Eyes on Me, in 1996. It didn’t take long for the album to go platinum. This album came with another big hit song, “California Love.” Another hit from the album was “How Do You Want It,” which also reached number one in pop and R&B charts. This album talked about the time he spent incarcerated, his feud with the East Coast, and his love-hate relationship with women.15

Between signing with Death Row Records and the feud going on with the East Coast and West Coast, Tupac started to show his dissatisfaction with the hip-hop and R&B industry. He began to realize that his music career was his downfall, that it was where his troubles all started.16 On September 7, 1996, Tupac Shakur was shot after leaving the Mike Tyson vs. Bruce Seldon fight at the MGM Grand Hotel in Las Vegas. He remained alive for a week before his condition worsened, and he passed away on September 13, 1996.17 With his death he became even more famous. Death Row released the album he was currently working on at the time of his death, proving that Tupac’s legacy would still go on through his music even though his life was over.18 To this day, Tupac is still one of the most influential rappers who has ever lived. His music was much more than just rap. It was, and continues to be, the story of his life, which was a life that influenced people around the world and gave people music that they could relate to.19

- Baker’s Biographical Dictionary of Popular Musicians Since 1990, 2004, s.v. “2pac,” by Shawn Gillen. ↵

- St. James Encyclopedia of Popular Culture, 2013, s.v. “Shakur Tupac (1971-1996),” by Pierre-Damien Mvuyekure. ↵

- The Scribner Encyclopedia of American Lives, 2001, s.v. “Shakur, Tupac Amaru,” by Louise Continelli. ↵

- Contemporary Black Biography, 1997, s.v. “Shakur, Tupac 1971-1996,” by Simon Glickman. ↵

- The Scribner Encyclopedia of American Lives, 2001, s.v. “Shakur, Tupac Amaru,” by Louise Continelli. ↵

- Encyclopedia of African American History, 2010, s.v. “Shakur, Tupac,” by Aaron D. Sachs. ↵

- The Scribner Encyclopedia of American Lives, 2001, s.v. “Shakur, Tupac Amaru,” by Louise Continelli. ↵

- Contemporary Black Biography, 1997, s.v. “Shakur, Tupac 1971-1996,” by Simon Glickman. ↵

- The Scribner Encyclopedia of American Lives, 2001, s.v. “Shakur, Tupac Amaru,” by Louise Continelli. ↵

- Baker’s Biographical Dictionary of Popular Musicians Since 1990, 2004, s.v. “2pac,” by Shawn Gillen. ↵

- Contemporary Black Biography, 1997, s.v. “Shakur, Tupac 1971-1996,” by Simon Glickman. ↵

- St. James Encyclopedia of Popular Culture, 2013, s.v. “Shakur Tupac (1971-1996),” by Pierre-Damien Mvuyekure. ↵

- The Scribner Encyclopedia of American Lives, 2001, s.v. “Shakur, Tupac Amaru,” by Louise Continelli. ↵

- St. James Encyclopedia of Popular Culture, 2013, s.v. “Shakur Tupac (1971-1996),” by Pierre-Damien Mvuyekure. ↵

- Baker’s Biographical Dictionary of Popular Musicians Since 1990, 2004, s.v. “2pac,” by Shawn Gillen. ↵

- Encyclopedia of African American History, 2010, s.v. “Shakur, Tupac,” by Aaron D. Sachs. ↵

- Baker’s Biographical Dictionary of Popular Musicians Since 1990, 2004, s.v. “2pac,” by Shawn Gillen. ↵

- The Scribner Encyclopedia of American Lives, 2001, s.v. “Shakur, Tupac Amaru,” by Louise Continelli. ↵

- Angela Ardis, Inside A Thug’s Heart (Kensington: Kensington Publishing Corporations, 2004), 207-208. ↵

Tags from the story

Hip-Hop Music

Tupac Shakur