October 1, 2018

The United States Exposed: Ron Ridenhour Reveals the My Lai Massacre

When one hears the word “Pinkville,” one imagines a cute, quaint village, right? However, the real Pinkville is the exact opposite of this perception. Pinkville was a term U.S. soldiers coined the Vietnamese village of My Lai, where one of the most inhumane moments of the Vietnam War happened. Blood, rape, and the screams from the brutal murder of children, women, and elderly are burned into our minds when we envision the My Lai Massacre in 1968.1

The Vietnam War began in 1954 when communist leader Ho-chi-minh defeated the French, who had colonized Vietnam in 1887. North and South Vietnam battled over their new government, as South Vietnam desperately tried to resist communist control. Amidst the heat of the Cold War between America and the Soviet Union, and afraid that communism would spread throughout Southeast Asia, the U.S. government ordered military involvement in 1964. The U.S. drafted healthy men age 18 or older to fight the war in Vietnam. Being a soldier stationed in Vietnam at this time came with immense stress. Spread thin, American soldiers were stationed in Vietnam for double the time a soldier was normally deployed, and they were only allowed a one month break, adding to this high amount of tension. There, soldiers saw incredibly brutal things daily — children were often used as weapons by the Vietnamese army and the language barrier made it incredibly hard to distinguish between friend and enemy. One soldier described their encounter with “gooks,” an extremely derogative term for Southeast Asians, “At first there was some confusion. How did you tell gooks from the good Vietnamese, for instance? After a while it became clear. You didn’t have to. All gooks were [Vietnamese Communist] when they were dead.”2 U.S. soldiers developed paranoia, and although the exact reason why the U.S. Commanders ordered the massacre is not known, one can presume it was due to the uneasy situation between the U.S. soldiers and the Vietnamese, which also led to the brutality at Pinkville.3

The U.S. military believed that Pinkville was booby-trapped to the extreme, and it was unknown whether or not the residents supported the Vietnamese communists, also referred to as Vietcong. Because of this, an order was placed by the Charlie Company — a unit of the U.S. Army American Division — to destroy all of the village inhabitants, and to leave no survivors. This order led to the most brutal and controversial massacre of the U.S. Army’s history. After the order was placed, the My Lai massacre was led by Lieutenant William Calley, followed by another Charlie Company unit, and it involved the vicious murder and rape 300 to 500 of women, children, and elderly civilians.4However, this dark moment in history remained a secret. It was not revealed to the U.S. public or even the U.S. government until months after the event had taken place.

Ron Ridenhour, a U.S. soldier who was serving in Vietnam at the time, played a central role in exposing the events that happened in the previously peaceful village of My Lai. Ridenhour was a helicopter gunner that had been drafted to the army at the same time as a man named Mike Terry. There, they became close friends, separated only once to different divisions when Terry was assigned to Lt. Calley’s platoon. That one separation caused a major change in Terry when he and Ridenhour were eventually reunited after being assigned to the same unit. Previous to their separation, Ridenhour thought Terry to be the definition of innocence as Terry was firm in his religious beliefs. Ridenhour was hit with the shock of his life when Terry told him the events that occurred in My Lai.5

Ridenhour, although not present at the event, began to hear about the events that took place at My Lai from Terry.6 Although Terry only participated in mercy killings to eliminate those who were mortally wounded and prevent them from suffering further, shock and horror filled Ridenhour as he heard about the rest of the gruesome details. Ridenhour, in absolute disbelief, almost refused to believe the event occurred. Determined to uncover the truth, he then consulted numerous other soldiers, expecting denial of this brutality, but instead, the soldiers added more horrific information to the massacre that occurred that day. Spurred to action, Ridenhour wrote a letter to President Richard Nixon and thirty Congressmen about these findings. In his letter, he recounted the numerous statements he had heard from soldiers who were at this massacre. Ridenhour recalled one soldier’s encounter with a Vietnamese child about three or four years old, who had been shot in the arm, “The boy was clutching his wounded arm… while blood trickled between his fingers… He just stood there with big eyes staring around like he didn’t understand… Then the captain’s [radio operator] put a burst of M16 fire into him…”7 He continued to describe more encounters, and even recalled the story of a soldier who shot himself in the foot to get out of participating in the massacre. Further testimonies describe the “bayoneting, clubbing, and close-range shooting” of unarmed civilians.8 Ridenhour also described how the soldiers systematically lined up villagers along a ditch and fired into them, comparing it to the Holocaust.9 Angry that this event happened and dedicated to exposing these horrors to get justice, he urged the U.S. to pursue an investigation, and he ends the letter with the fact that he had considered sending this story to the reporters and newspapers to add pressure to the government to follow through with the investigation.10

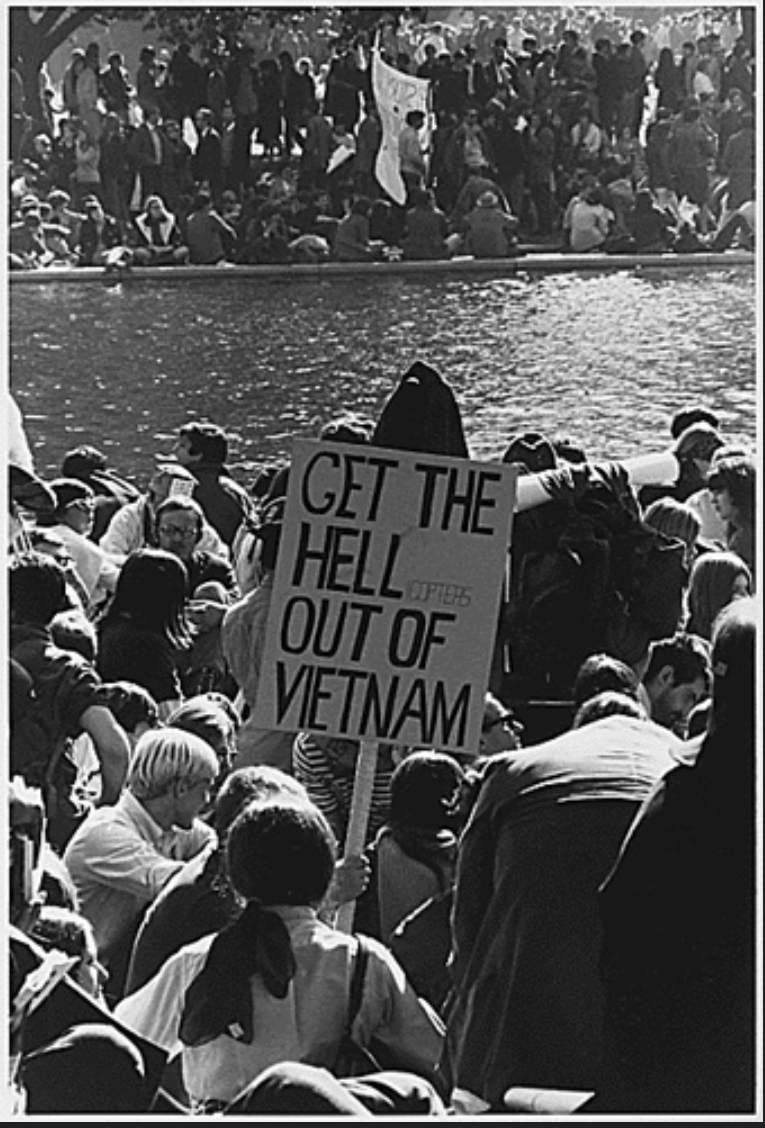

After the investigation was exposed to the public, Ridenhour felt that the government “whitewashed” the event and wanted justice.11 With the help of a reporter named Seymour Hersh, they exposed the brutal event to the public, causing a rise of emotions globally. The massacre sparked controversy, disbelief, disgust, and anger in the public, especially among the American people. Ridenhour’s shock at even Terry’s involvement in the massacre mirrored the U.S. public’s shock as it unveiled the truth of what the Army and U.S. government were doing overseas. The My Lai Massacre became a turning point in the Vietnam War regarding U.S. involvement, leading many people to adamantly question if U.S. involvement in Vietnam was doing more harm than good. There had already been many protests against the involvement of the U.S. in the Vietnam War and against the draft targeting people of color. However, after Ridenhour exposed the massacre, protests increased exponentially among the American public. Eventually, these protests helped pressure the U.S. government to move troops out of Vietnam.12

Charges were brought up against thirty soldiers after the incident of My Lai was exposed, but only one person was convicted — Lieutenant Calley. Ridenhour believed the U.S. Army and the government used Calley as a scapegoat for all of the U.S. troops involved that day, since Calley was the lowest ranking officer leading this massacre. He was sentenced to life in prison, but due to the enormous amount of publicity regarding the massacre, it was deemed that his trial was unfair and too harshly affected by public view. His sentence was decreased to 20 years, and then to 10 years, after which President Nixon intervened and he served a three-year house arrest sentence.13

Although this massacre is shrouded in injustice for the hundreds of women, children, and elderly that lost their lives that day, Ridenhour and the few U.S. soldiers that risked their lives to go against orders and save as many Vietnamese civilians as possible represent those with true bravery and dedication to justice. Ron Ridenhour played a major role as the My Lai whistle blower, helping bring the truth of the injustice that happened to hundreds of innocent people in the village of My Lai to the public. Today, Ridenhour Prizes are awarded to journalists who follow Ridenhour’s example of being dedicated to truth telling in their writing and protecting social justice. These awards demonstrate the long-lasting importance of Ridenhour’s act of integrity and truthfulness.

- Donna Batten, “My Lai Massacre,” Gale Encyclopedia of American Law, 3rd ed., Vol. 7. (Detroit: Gale, 2010), 164-165. ↵

- Dan Duffy, and Tal Kali, The Viet Nam Generation Big Book (Woodbridge, Conn. : Viet Nam Generation Inc, 1994), 203-214. ↵

- Donna Batten, “My Lai Massacre,” Gale Encyclopedia of American Law, 3rd ed., Vol. 7. (Detroit: Gale, 2010), 164-165. ↵

- Ian Shapira, “‘It was Insanity’: At My Lai, U.S. soldiers slaughtered hundreds of Vietnamese women and kids,” Washington Post, March 16, 2018. ↵

- Dan Duffy, and Tal Kali, The Viet Nam Generation Big Book, (Woodbridge, Conn. : Viet Nam Generation Inc, 1994), 203-214. ↵

- Dan Duffy, and Tal Kali, The Viet Nam Generation Big Book, (Woodbridge, Conn. : Viet Nam Generation Inc, 1994), 203-214. ↵

- Lily Rothman, “Read The Letter That Changed the Way Americans Saw the Vietnam War,” Time Magazine, March 16, 2015. ↵

- Stephen L. Carter, “My Lai Revisited,” Newsweek, April 2, 2012, 19. ↵

- Ron Ridenhour, “Perspective on My Lai: ‘It was a Nazi kind of thing,’” Los Angeles Times, March 16, 1993. ↵

- Lily Rothman, “Read The Letter That Changed the Way Americans Saw the Vietnam War,” Time Magazine, March 16, 2015. ↵

- John H. Jr. Cushman, “Ronald Ridenhour, 52, Veteran Who Reported My Lai Massacre,” New York Times, May 11, 1998. ↵

- Donna Batten, “My Lai Massacre,” Gale Encyclopedia of American Law, 3rd ed., Vol. 7. (Detroit: Gale, 2010), 164-165. ↵

- Cynthia Rose, “Lieutenant Calley: His Own Story,” American Decades Primary Sources, Vol. 8, 1970-1979 (Detroit: Gale, 2004), 297-301. ↵

Tags from the story

Journalism

My Lai Massacre

Ron Ridenhour

The Year 1968

Vietnam

Vietnam War

Sarah Nguyen

StMU’s 5th Semi-Annual Award Ceremony Co-Chair, 2018 | Computer Engineering major

Author Portfolio Page