The Kingdom of Heaven is in turmoil. Muslim Caliphates and Christian Kingdoms go toe-to-toe on the battlefield, sending armies of soldiers into a Medieval meat grinder in a desperate attempt to establish control over the Holy Land. Eager knights from all over Europe take up the cross and traverse to Jerusalem in search of spiritual glory. Out of all the knightly orders, however, only one would reach such a level of infamy, whose name would be sung in praise by rich and poor alike across Christian Europe: The Knights Templar.

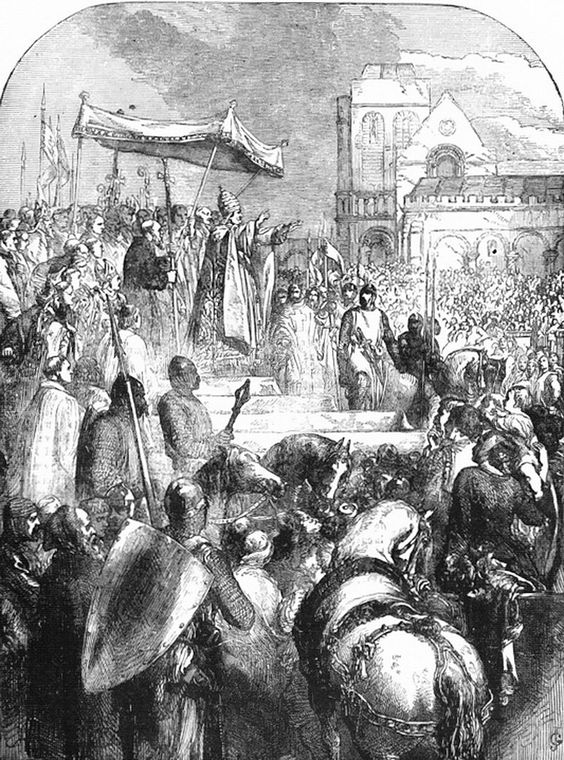

The origin of the Templars can be traced back to the First Crusade, in which many knights, mainly those of Frankish descent, chose to take up the sword against the Saracens (Crusader slang meaning “infidels”). At the time, Jerusalem had fallen to the armies of the Seljuk Turks, a nomadic people from the steppes of Central Asia. The Seljuks prided themselves on a policy of religious intolerance; Christians were barred from the Holy City, and often subject to harassment and second-class citizenry. Furthermore, the expansionist ambitions of the Turkish Sultan was particularly concerning to the Papacy and its subjects, and even far more so to the Byzantines. Despite their religious differences, the Byzantine Emperor petitioned the Western Empire for help; Seljuk expansion and dominance threatened Byzantine sovereignty in the region, and therefore, Christian interests. As the last standing bastion of Christian might in the Near East, the survival of the Byzantine Empire was crucial, and a Muslim Jerusalem provided a base for Seljuk raiders to stage further attacks on Byzantine territory. If Constantinople fell to the Seljuks and their Arab cousins, then it would open the door for Muslim hordes to rampage further into Europe; considering that the Moors had already conquered Visigothic Spain seemingly without any resistance, the idea of another Islamic incursion into Europe frightened Christians to the core. European Christendom needed a faithful, God-fearing savior to step up to the plate, and the key to salvation was held by none other than the Holy Father himself: Pope Urban II. On November 27, 1095, Pope Urban II declared the First Crusade in a powerful speech in Clermont, France. The effectiveness of Urban’s speech cannot be overstated; it sent shockwaves all throughout Christian Europe, filling the common peasant, blacksmith, soldier, and aristocrat with a spiritual fervor Europe had not seen since ages past. Cries of “Deus Vult!” (God wills it) echoed loudly all across the land. The Pope even promised a remission of sins for all those who volunteered for battle, which proved to be enough incentive for many European Christians that were constantly constantly searching for any inkling of Christ’s salvation. 1 In 1098, the Shia Fatimids of Egypt had pushed the Seljuks out of Jerusalem, but even they were no match for Europe’s vengeful crusader army. Under the spiritual and military leadership of Peter The Hermit, a respected French priest, and the French nobleman Godfrey De Bouillon, a Frankish army seized Jerusalem from the Fatimid Egyptians in an utter massacre. Muslim men, women, and children were all put to the sword. Caught in the middle of it all were the Jews of Europe and of Jerusalem, who were subsequently mass-murdered and hunted down all across the Rhineland by Peter’s army, and subject to even further abuse, torture, and murder in the land of Israel. Eyewitness accounts from those present during the siege of Jerusalem attest that so great was the slaughter that it was impossible to walk on the Temple Mount without tripping over a corpse. Following the bloody battle, any Fatimids or Jews that were spared by the crusaders were expelled to other nearby realms or sold into slavery. The Franks emerged victorious; and by 1099, the Kingdom of Jerusalem was established, with Godfrey De Bouillon installed as its first king. The First Crusade had come to an end.2

Under Christian leadership, Jerusalem prospered. Access to Christian holy sites, which had previously been restricted during Muslim rule, were restored. However, Muslim bandits in the Outremer (referring to the territory outside of the Kingdom of Jerusalem) still remained a threat to Christian pilgrims. Arab raiders took a delight in robbing, often times slaughtering in the process, the Christian pilgrims that had chosen to make the long trek to Jerusalem. Nearly twenty years after the fall of the city to Christian forces, an ambitious French knight decided to approach the king with a solution. In 1119, Hugh of Payns, along with a smaller group of faithful knights, appeared before King Baldwin II and Warmund, Patriarch of Jerusalem, with one thing in mind: to establish a knightly order of monastic warriors dedicated to preserving the Christian integrity of Jerusalem, its honor and security thereof, and the lives of European pilgrims. After some discussion at the court, King Baldwin and Patriarch Warmund approved Hugh’s proposal. That same year, Hugh and his fellow knights gathered on the Temple Mount in what is now the Al-Aqsa Mosque, and took their monastic oaths, swearing to poverty, celibacy, and brotherhood. On the fateful day of December 25, 1119, Hugh of Payns was elected to the position of Grandmaster, and the knights took their vows before the king and patriarch; the “Poor Fellow Soldiers of Christ and the Temple Of Solomon,” or the Templar Order, was born.3

There was one final piece of the puzzle to solve before the Templars could get to work: finances, and Papal recognition. Although the Templars took vows of personal poverty, the order still required a steady revenue to purchase weapons, armor, and provisions for the knights, and papal recognition could help to boost recruitment drives and morale. The Templars found a powerful ally in Bernard of Clairvaux, patron saint of the order, who spiritually sponsored the Templars and provided them with a clear code of conduct.4 Pope Honorius was more than pleased; he saw great potential in the members of the order, and they were granted official Papal recognition in 1129. Furthermore, the Pope granted the Templars the permission to wear the infamous ice-white mantles donned with a red cross, setting them apart as holy warriors and defenders of the Christian faith. The hair on their heads was to be cut short, and they were not permitted to shave their beards. Following this amazing milestone, the impoverished state of the Templars didn’t last long. Money in the form of charitable donations from the European aristocracy began to flow into the palms of the order like an unstoppable flood. The Templars, due to their honest and knightly reputation among European Christians, were viewed as legitimate bankers and a worthy investment. Before they knew it, the Order was sitting on a gold mine, fully financed with the wealth of Europe.5

For years, Rome maintained a two-pronged approach in the Holy Land. The Templars maintained their status as the dominant Crusader force and successfully performed their functions as European bankers and elite foot soldiers. In their conquests and many raids, certain high-profile Templars had acquired castles, lands, and estates either granted by European aristocrats or seized from Muslim land owners. The order maintained a steady rivalry with the Order of the Knights of the Hospital of St. John of Jerusalem, or the Knights Hospitaller, whose primary job, besides serving as another military strong arm of the Roman Church, was to treat sick or injured pilgrims. Rivalry aside, the assistance of both orders was crucial in defending and securing the newly established Crusader states of Tripoli, Edessa, and Antioch. Even considering that the Templars and Hospitallers had put rivalry aside for the betterment of Christendom, squabbles among the crusader states proved a greater danger. Internal division caused the Franks to let their guards down, and Edessa had subsequently fallen into the hands of Zengi of Mosul, a Muslim warlord. In a series of unfortunate events, Zengi managed to take Edessa without a fight and slaughtered all of its Christian inhabitants: men, women, and children. Zengi continued to wave his fists at the crusader states and the Byzantines, with the threat of taking Damascus as well. The Edessa fiasco proved to be a major loss for the Crusaders in the East; but in 1145, Pope Eugenius III wrote to King Louis VII of France and requested that he spearhead another crusade. King Louis agreed, and arranged for Bernard of Clairvaux to speak at Vézelay. Joined by an army of Templar Knights, the Pope and King Louis met in France at the Paris Templar Temple and announced the coming of the Second Crusade. Bernard of Clairvaux also petitioned Conrad III, king of Germany, to assist Louis in his campaign. Conrad happily obliged; now, with two united armies propped up by elite Templar foot soldiers, the forces of Christian Rome seemed unstoppable. The target was Damascus, which the crusaders hoped to seize from Nur Al Din, the son of Zengi, in an effort to exact vengeance for the slaughter at Edessa. Unfortunately, disaster stuck when the army of King Conrad III was massacred by Seljuk raiders near Constantinople. Conrad, who survived the battle, retreated to Nicaea and joined up with Louis’ army. However, the French Army was low on morale and provisions, and stood no chance against the mounted cavalry of the Turks. Despite the heavy losses, the French Army still attempted to seize Damascus, but had no choice but to withdraw after their failed attempts to breach the city walls. The Second Crusade ended as quickly as it started, marking the Templars with an embarrassing defeat.6

Following the disastrous events of the Second Crusade, a new king had risen in Jerusalem. Almaric had succeeded his brother, Baldwin III, as king of Jerusalem and launched campaigns into Fatimid Egypt to deter Nur Al-Din from establishing control there. The Templars certainly did not take the opportunity to redeem themselves from the charade at Damascus—and due to disagreements over strategic matters, refused Almaric’s request to garrison his army with Templar soldiers. As a result, Egypt fell to Nur Al-Din’s forces, paving the way for a new and far more powerful Muslim ruler to step onto the scene. The Fatimid caliph Al-Adid died in 1171, and his liege Nur Al-Din died only three years later. Egypt was in chaos, and without a ruler. The only person that was closest in line to the throne was Egypt’s vizier, a man known as Salah Al-Din Al Ayubi, or Saladin. Saladin was a Sunni Muslim, a Kurd, and an exceptional military leader.7 Following the death of Nur Al-Din and the caliph, Saladin proclaimed himself as Sultan of Egypt and Syria. A storm was brewing on the horizon, to be sure—Muslim armies were gathering in Outremer, and Saladin began to make his desire to reconquer Jerusalem public.8

The drums of war were sounding, and it was time for the Templar Order to face its biggest challenge yet—stopping Sultan Saladin’s rampage dead in its tracks. The Templars were lusting for blood and battle, for it could never come to pass that a Saracen would sit on Jerusalem’s throne ever again. Jerusalem’s redemption rested upon the shoulders of its young but powerful ruler, “The Leper King” Baldwin IV. Baldwin was the son of Almaric, and was crowned king shortly after Almaric’s death. He began to express signs of leprosy from as early as nine years old; however, despite the fact that Baldwin had lost all feeling in both his hands and feet by the time he reached his twenties, he still proved to be an efficient administrator, warrior, and formidable opponent to Saladin.9 On November 25, 1177, a sixteen-year old Baldwin marched to Gaza with an army of knights and Templars to meet Saladin on the battlefield; and this time, the Templars had chosen to go with their king. The crusader army, led by Reynald De Chatillon, Prince of Antioch, was vastly outnumbered; but if they held the line, they would be able to halt Saladin’s march to Jerusalem. While Saladin’s army was crossing a ravine at Montgisard, near Ramleh, Baldwin and the Templars took them by surprise. What followed was a close battle—Muslim and Christian soldiers smashed into each other with brute force, iron clashed with iron. Against all odds, the small crusader force overcame Saladin, and sent him and his army fleeing back to Egypt with their tails between their legs.10

In May 1180, after the Battle of Montgisard, Baldwin and Saladin agreed to a two-year truce. Besides the land suffering from a severe drought and producing poor harvests, the summer months were simply too hot for the two exhausted armies to engage each other. Unfortunately, however, Reynald de Chatillon took matters into his own hands and broke the truce a year later. From his castle at Kerak (modern day Jordan) Reynald plundered a passing Muslim caravan and murdered its merchants. Saladin demanded compensation, but Reynald refused the Sultan’s request and launched naval raids on Arab merchant ships in the Red Sea, provoking him even further. By 1182, Saladin was marching once again from Cairo with an invasion army ready to take Jerusalem. On the West Bank of the Jordan waited Baldwin, who, despite the fact that he was nearing his death, chose to participate in the battle anyway. In yet another skirmish, Saladin was repelled; but this was just the beginning. Saladin had consolidated his power by seizing Aleppo from the last of Nur Al-Din’s minions, and now had the Crusader states completely surrounded. King Baldwin finally succumbed to his leprosy, and died in March 1185—at the same time, the Templars elected Gerard of Ridefort as their new Grandmaster. Baldwin left behind no suitable heir, and the throne passed on to his brother-in-law, Guy de Lusignan.11

Following Baldwin’s death, things began to look bleak for the Templars. In April of 1187, King Guy sent an army of Templars and Hospitallers into Galilee to quell a potential coup staged by Count Raymond of Tripoli. Although Balian of Ibelin urged Guy to hold off his attack and send a delegation to meet Raymond instead, their meeting was disrupted when Raymond notified Guy of a tip regarding a Muslim scouting party nearby. When Gerard of Ridefort heard the news, he summoned his Templars and the Hospitaller Grandmaster to accompany him in search of Saladin’s alleged scouts. The men rode towards the valley at Nazareth, and much to their surprise, stumbled upon seven thousand of Saladin’s elite Mamluk cavalry watering their horses at the Springs of Cresson. The Templar marshal and the Hospitaller Grandmaster advised a retreat, but Gerard of Rideford irresponsibly insisted on attack. The Templars charged with fearless bravery, but their army was annihilated almost instantly. Only Gerard of Ridefort and three others escaped with their lives; the Mamluks made trophies of the Templar’s heads, and placed them on pikes throughout Galilee.12

Saladin’s attacks didn’t stop there. Over the border, the Sultan was gathering a massive Muslim army of 18,000 men strong. King Guy raised an army of 12,000 knights, filled with fighting regimens of Templars and Hospitallers. Saladin marched his army to siege out the city of Tiberias, and the Crusaders marched their army to the plains of Galilee to meet him. In an unforeseen turn of events, a message arrived from Count Raymond’s wife, who was trapped within the walls of Tiberias. King Guy immediately held a council at his tent, in which Reynald de Chatillon, Gerard of Ridefort, Balian of Ibelin, and Count Raymond were all present. A debate ensued as to whether or not Tiberias should be defended or abandoned; and later that night, Gerard of Ridefort came to King Guy in confidence, pinning Count Raymond as a traitor and saying that to abandon Tiberias would be an embarrassment to the Templars, as well as the King’s honor. Guy took Gerard’s advice to heart, and decided to give the order to march on Tiberias at dawn. This decision proved to be catastrophic—in the heat of July, there was no water along the road, and the men were increasingly suffering from heat exhaustion. Saladin was a step ahead of the Templars, and had seized the watered village of Hattin; the Christian army had no choice but to encamp themselves on the dry Hattin plateau for the night, with still no sign of water in sight. By sunrise the next day, Saladin attacked. Although the Templars put up a serious fight, many of the Templar knights, including the Hospitallers accompanying them, were slaughtered by Saladin’s light cavalry. Only Balian and Count Raymond escaped, while King Guy, Reynald de Chatillon, and Gerard of Ridefort were all taken prisoner. Saladin personally beheaded Reynald de Chatillon, along with many of the Templar and Hospitaller survivors, both of which he attributed as “impure races.” Gerard of Ridefort was surprisingly spared, and any other knights that didn’t fall victim to Saladin’s rage were sold into slavery.13

Hattin marked a devastating losing streak for the Templars. Indeed, the order had not experienced such an embarrassment since the disaster at Damascus during King Louis’ Second Crusade. As a result of the loss at Hattin, Jerusalem was just within Saladin’s reach, and there was nobody to stand against him. On September 20, Saladin and his great army surrounded Jerusalem. Only Balian of Ibelin remained as the last standing lord within the city, and he understood that to fight against Saladin would only result in a mass slaughter of Christians and further bloodshed between the two faiths. Balian and the Patriarch sent word to Saladin to seek terms, and Saladin agreed. Saladin’s terms were simple: if Balian surrendered the city, Saladin would allow all of Jerusalem’s 20,000 Christians, men, women, and children, to leave safely. Balian agreed, and the terms were set. On October 2, 1187, Saladin’s army entered Jerusalem. The last remaining Templar leadership was expelled from the Al-Aqsa mosque, and any structures the Templars had built on the Temple Mount were demolished by Saladin’s troops. The cross put atop the Dome Of The Rock was toppled, replaced with the Islamic star and crescent; Jerusalem was lost.14

Despite the fact that Jerusalem had fallen to the Muslims, the Templars would still continue to play a great role in the Holy Land and in Europe. At the turn of the century, the Templars were pushed to their strongholds in the north at Acre and Tortosa, continuing to launch attacks against Muslim territory in hopes of regaining previously lost ground. Arguably, the golden age of the Templars would come in the centuries following Saladin’s conquest of Jerusalem; and for the next two hundred years, they would assist in further Christian crusades to the East. In 1190, King Richard “The Lionheart” of England partnered with King Phillip II of France, and launched a series of successful campaigns against Saladin during the Third Crusade.15 But Jerusalem, however, would never see another Christian ascend to its throne. For nearly five hundred years, Jerusalem would be under Muslim control until the collapse of the Ottoman Empire in the twentieth century. It wasn’t until the 1967 Six Day War fought between the state of Israel and its Arab neighbors that Jerusalem came under the control of an independent Jewish entity; something that had not happened since the destruction of the First Temple and the Kingdom of Judah at the hands of the Babylonians. Even so, peace in the Holy Land remained seemingly out of reach.

Over nine hundred years after the First Crusade, and seven hundred years after the destruction of the Templars, the battle for Jerusalem still continues.

- Michael Haag, The Templars: The History & The Myth, First US Edition (195 Broadway, New York, NY 10007: Harper Collins, 2009), 73-75 ↵

- Michael Haag, The Templars: The History & The Myth, First US Edition (195 Broadway, New York, NY 10007: Harper Collins, 2009), 71-83. ↵

- Mark Cartwright, “Knights Templar,” World History Encyclopedia, accessed October 28, 2021, https://www.worldhistory.org/Knights_Templar/. ↵

- Michael Haag, The Templars: The History & The Myth, First US Edition (195 Broadway, New York, NY 10007: Harper Collins, 2009), 99-101. ↵

- Mark Cartwright, “Knights Templar,” World History Encyclopedia, accessed October 28, 2021, https://www.worldhistory.org/Knights_Templar/. ↵

- Michael Haag, The Templars: The History & The Myth, First US Edition (195 Broadway, New York, NY 10007: Harper Collins, 2009), 112-123. ↵

- Paul E Walker, “Saladin | Biography, Achievements, Crusades, & Facts,” Encyclopedia Britannica, accessed October 5, 2021, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Saladin. ↵

- Michael Haag, The Templars: The History & The Myth, First US Edition (195 Broadway, New York, NY 10007: Harper Collins, 2009), 161-165. ↵

- Real Crusades History, Baldwin IV – The Leper Crusader King – Full Documentary, 2019, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3Iv4glbNKSs. ↵

- Michael Haag, The Templars: The History & The Myth, First US Edition (195 Broadway, New York, NY 10007: Harper Collins, 2009), 165-166. ↵

- Michael Haag, The Templars: The History & The Myth, First US Edition (195 Broadway, New York, NY 10007: Harper Collins, 2009), 166-170. ↵

- Michael Haag, The Templars: The History & The Myth, First US Edition (195 Broadway, New York, NY 10007: Harper Collins, 2009), 170-171. ↵

- Michael Haag, The Templars: The History & The Myth, First US Edition (195 Broadway, New York, NY 10007: Harper Collins, 2009), 171-176. ↵

- Michael Haag, The Templars: The History & The Myth, First US Edition (195 Broadway, New York, NY 10007: Harper Collins, 2009), 178-180. ↵

- Michael Haag, The Templars: The History & The Myth, First US Edition (195 Broadway, New York, NY 10007: Harper Collins, 2009), 181-182. ↵

12 comments

David Kamel

Great job!! this is crazy good, I am stunned by your writing and attention to detail. I love reading about the Templars and I think this story you tell is just uniquely amazing honestly. This really makes you think so much about history because you can always find something you didn’t know about and you do a great job of including in-depth information in such a short article!

Charles Lares

This article is very detailed and was very interesting to read. it was amazing to read about the Templars and the battle with the Muslim empire to see who would claim the land as theirs. the article introduced in-depth research about the first and second crusades. It introduced more information that I hadn’t heard about before in religion. The battle of the holy land continues to this day, and although it continues I think that it will never end.

Andrew Ponce

Through this article, one can tell that the author knows their audience and truly engages with them through his storytelling. The author very nicely selected an article that most people will take interest in, as well as give detailed history of the Templar and how their Frankish origin reflected events in the future. The article itself is very nicely drafted in how it states historical events, as well as explains why these events happened. It is easy to see why this author’s articles have been nominated for awards. Great work!

Madeline Chandler

This is such a well written engaging article. Very captivating and informative. I have read about a lot about the Crusades and all the many tactics taken in the approaches to religion and the military. Yet this article stood out. I truly found the origin of Templar so interesting and they had Frankish origin. Also, the fact that they made connections to Bernard of Clairvaux, a patron saint, is so fascination. And he created their code of conduct. Job well done! Enjoyed it!

Daniel Diaz

I always saw the Templars as less of a “religious” order and more of a “European normality” initiative. Around this time was the height of the caliphate and Europe was getting tired of the Muslims sending the Berbers to do their bidding so they started that order as an answer to this colonizing threat. Good job.

Jaedean Leija

your writing skills have really shown you wrote two articles and both are nominated for an award. I really hope you win one, learning about the crusades is new and interesting. You have chosen a topic that I feel like everyone will take interest in, you were able to explain the history and roles about both groups and you didn’t care how long your article was as long as you got your point or story telling told to the fullest. great article!

Martha Nava

I like how you didn’t hold back on the length of the article and showcased your writing skills. I think this was very informative and definitely nomination-worthy! I had not heard of The Knights Templar before but it was interesting to read what they did and the battles they went through. I also think the article was more enjoyable since you can see the passion behind the topic.

Phylisha Liscano

This was a very interesting article and very informative. The topic you picked was very interesting and fascinating. To be honest I have not done much research on the Templar knights and your article helped me learn a little more. You provided lots of information and great images. Overall great article and I enjoyed getting the chance to read your article.

Trenton Boudreaux

It is fascinating how one city could come to influence much of European and Middle Eastern history. I suppose that is just what happens when three of the world’s major religions value Jerusalem as a holy site. I doubt that we will ever see any peace at the holy land, as it has been contested for millennia by multiple groups. A very well researched article on a historically significant group of warriors.

Matthew Gallardo

I had heard of the Templar knights and have seen their iconic uniform throughout my life, but I never really knew their roots and history apart from that they originated during the Christian occupation of Jerusalem. I also never knew that Saladin lived during the same era as their existence and resulted in their expelling from Jerusalem, but this article has taught me so much regarding the order that is so easily recognizable today.