In the United States in the 1920s, life was drastically different. Socialism in the United States was growing in popularity, both for American voters and in the media. Eugene V. Debs, a pioneer who paved the way for the Socialist movement in the United States at the turn of the twentieth century faced a challenge that would change the course of America’s history forever, for the better or worse. Debs was on a mission to become the President of the United States, a quest that he had previously attempted four times before, in 1900, 1904, 1908, and 1912, and he also intended to run again in 1920. The pivotal moment in Deb’s career began in the summer of 1918, in the small town of Canton, Ohio, where Debs was speaking at an annual picnic for the American Socialist Party. Here, Debs gathered thousands of supporters and voters to portray his ideals and use his platform to educate others on socialist ideals, as well as speak on injustices that he found important.1

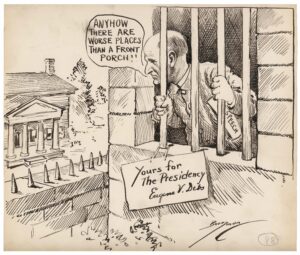

At the annual party picnic in Ohio, Debs felt it important to address his disdain for the war draft and the implications that it had for United States citizens, which was being used at the time to involuntarily enlist young men in the United States to serve in the armed forces during the First World War. He regularly expressed the importance of social reform, and he denounced the war, which included what was arguably his most controversial speech, being delivered in Canton, although this speech was much like many others he gave.2 Debs expressed that he felt there was hypocrisy in how it was “extremely dangerous to exercise the constitutional right of free speech in a country fighting to make democracy safe for the world.”3 He also was sure to mention his disapproval of the Wilson administration’s preparedness program, criticizing the president’s handling of the war.4 He strongly disapproved of the war, stating, “They have always taught and trained you to believe it to be your patriotic duty to go to war and to have yourselves slaughtered at their command. But in all the history of the world you, the people, have never had a voice in declaring war, and strange as it certainly appears, no war by any nation in any age has ever been declared by the people.” 5 This statement and more led to a pivotal halt in Deb’s career. A sedition charge would forever immortalize Debs as the first and only Presidential candidate to run for President from a federal penitentiary to date. Many news outlets portrayed him as a dictator or traitor, despite his many advocates who would regularly gather in the streets in support of him whenever he was close to supporters. The Washington Post was one of many outlets writing scandalous headlines, chronicling “DEBS INVITES ARREST.”6

Deb’s trial was quite extensive. It began on September 10, 1918, in Cleveland, Ohio, a mere three months after the famous speech in Ohio. He was charged with sedition under the Espionage Act, which coincidentally was only enacted the previous year.7 Debs chose to go the route of admitting to the crime that he was accused of but argued that the Espionage Act was an attack on the First Amendment, and was therefore unconstitutional. Espionage Act cases were commonly lost at this time, and Debs’ case was no different. There were many accusations brought against him, one of the most serious being that there was reason to believe that draft-age men listened to Deb’s speech against the war draft, and as a consequence, may have shirked their duties to the United States government to serve. However, all men who were cross-examined had done their civic duty and registered, proving this claim to be a weak one, despite the thousands who either had failed to register or deserted in 1918. The trial concluded with one of Deb’s most famous speeches, in which he addressed the jurors to convey his lack of remorse for his act. Although uncommon, Debs insisted that he address the jury personally, saying, “Standing before you, charged as I am with crime, I can yet look the Court in the face…there is festering no accusation of guilt.”8 He also spoke to his claim on the infringement of his First Amendment right, claiming “I believe in free speech, in war as well as in peace.”9 The trial eventually concluded with his defeat and the judge sentencing Debs to three concurrent ten-year sentences in a federal penitentiary, a huge loss for both Debs individually and the American Socialist Party as a whole. He spoke with the fiery passion that he became famous for, claiming that “If the Espionage Law stands, then the Constitution of the United States is dead.”10

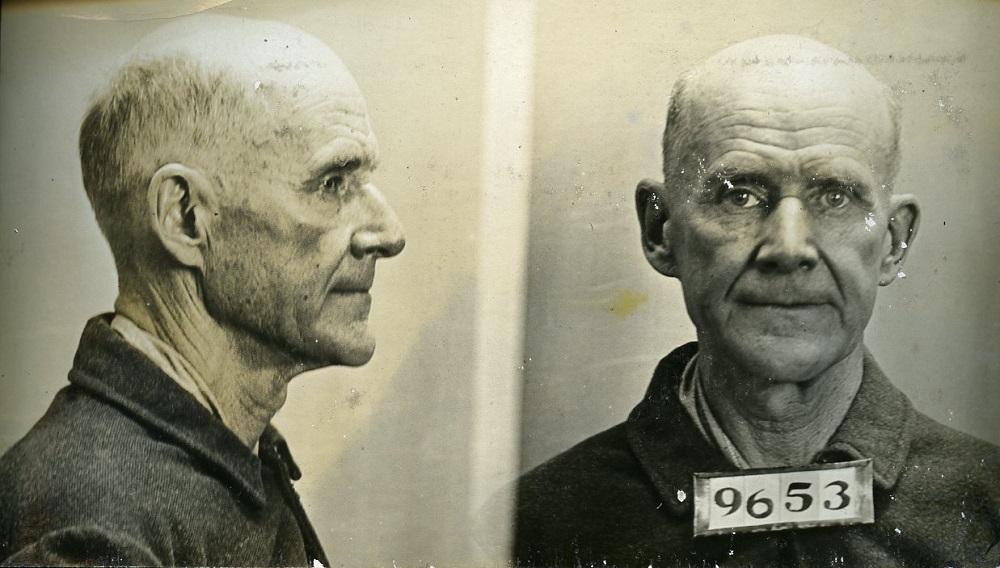

In an attempt to appeal his conviction, the Supreme Court ruled that the Espionage Act was to be upheld. In the case Debs v. United States, 249 U.S. 211 (1919), the court held that “his speech was intended to obstruct the war effort.”11 During the time surrounding the First World War, the Supreme Court ruled similarly on several cases regarding the limitation of speech.12 Although he did not believe in the possibility of a successful appeal, Debs was arrested in 1919 and sent to prison briefly in West Virginia before being permanently transferred to the federal institution in Atlanta, Georgia, from where he ran his final presidential campaign.13 Debs was expectedly outspoken about being imprisoned, writing a series of columns about his disdain for the prison system. In one excerpt of his writings from prison, he wrote, “I thank the capitalist masters for putting me here. They know where I belong under their criminal and corrupting system.”14

Debs’ campaign for the presidential race was quite blunt about Deb’s prison sentence and chose to embrace the unprecedented situation rather than shy away from it. Political buttons were regularly distributed, campaign buttons with his convict number on his uniform, capitalizing on his prisoner status and addressing the issue at hand. 15 He also began a campaign called from “Jail House to White House,” which shined his unfortunate situation in a positive light. 16 Although the party was becoming weaker around this time with membership declining, seeing Debs on the ballot despite the bumps in the road was empowering for America’s socialists. Two hundred socialists even traveled to Washington D.C. to pressure the Wilson administration to release Debs, among others. Although this was unsuccessful, there was no doubt that it garnered media coverage for Debs, who was well talked about by the American population at this time, whether he was loved or hated.17

By election night, Debs had amassed 913,664 votes, his second most successful turnout of the five. During and after the election, Debs had been in poor health, both mentally and physically. For starters, he had lost hope for the American population. After five unsuccessful attempts at becoming the first Socialist President of the United States, he lost his last race to a Republican administration that directly conflicted with Debs’ and the American Socialist Party’s views on how the United States should function. He suffered from a heart condition, which often gave him trouble when trying to sleep and go about his daily life while in prison, and was in mental anguish at witnessing and experiencing the atrocities that were committed at the penitentiary in Atlanta. These included seeing a fifth of the prison population perish from syphilis, a botched surgery, and the constant anguish of drug overdoses and fellow inmates in withdrawal. He also experienced multiple loved ones passing or becoming gravely ill while in prison, including his brother. Debs regarded that the conditions were so dangerous and isolating, that the inmates there were experiencing “abysmal depths of depravity that the lower animals do not know.”18

Although President Woodrow Wilson denied a proposition for a presidential pardon for Debs, on December 23, 1921, Debs received the news he had been waiting for. President Harding, who had come to office following Wilson, had decided to commutate his sentence, which the president was sure to differentiate from a pardon. While serving time, he attempted to petition for his release multiple times, getting denied at every turn. It was not until his presidential opponent and future 29th President of the United States, President Harding, commuted the four-time candidate and saw no imminent threat to his seditious acts. Harding was quoted about the situation saying, “There is no question of his guilt. . . . He is an old man, not strong physically. He is a man of much personal charm and impressive personality, which qualifications make him a dangerous man calculated to mislead the unthinking and affording excuse for those with criminal intent.”19 The process was quick and seemingly effortless because Harding released this statement on December 23, and declared that Debs was to be released on Christmas day, just two days following. On that Christmas morning in Atlanta, Georgia, thousands were lined up to celebrate his release from prison. Upon his release to a crowd of fifty thousand who were cheering his name, Debs was invited by President Harding to visit the White House to greet him personally. Harding jokingly told Debs, “Well, I’ve heard so damned much about you, Mr. Debs, that I am now glad to meet you personally.”20

- Melvin I. Urofsky, “Chapter 4: The Trial of Eugene V. Debs, 1918,” Justice and Legal Change on the Shores of Lake Erie : A History of the United States District Court for the Northern District of Ohio, Paul Finkelman and Roberta Sue Alexander, eds., (Ohio: Ohio University Press, 2012), 97-99. ↵

- J. Robert Constantine, “Eugene V. Debs: An American Paradox,” Monthly Labor Review 114, no. 8 (August 1, 1991): 33. ↵

- Eugene Debs’s Speech in Canton, Ohio June 16, 1918, Freedom of Speech : Documents Decoded, 2017. ↵

- J. Robert Constantine, “Eugene V. Debs: An American Paradox,” Monthly Labor Review 114, no. 8 (August 1, 1991): 33. ↵

- Eugene Debs’s Speech in Canton, Ohio June 16, 1918, Freedom of Speech : Documents Decoded, 2017. ↵

- Jill Lepore, “Eugene V. Debs and the Endurance of Socialism,” The New Yorker, accessed January 22, 2024, https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2019/02/18/eugene-v-debs-and-the-endurance-of-socialism ↵

- “Eugene V. Debs,” Britannica, accessed January 22, 2024, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Eugene-V-Debs ↵

- Ernest Freeberg, Democracy’s Prisoner : Eugene V. Debs, the Great War, and the Right to Dissent (New York: Harvard University Press, 2010),83-98. ↵

- Ernest Freeberg, Democracy’s Prisoner : Eugene V. Debs, the Great War, and the Right to Dissent (New York: Harvard University Press, 2010), 100. ↵

- Ernest Freeberg, “Democracy’s Prisoner : Eugene V. Debs, the Great War, and the Right to Dissent,” January 1, 2008, 100-107. ↵

- David Schultz and John R. Vile, The Encyclopedia of Civil Liberties in America (Armonk, N.Y.: Routledge, 2005), 258-260. ↵

- David Schultz and John R. Vile, The Encyclopedia of Civil Liberties in America (Armonk, N.Y.: Routledge, 2005), 258-260. ↵

- Melvin I. Urofsky, “Chapter 4: The Trial of Eugene V. Debs, 1918,” Justice and Legal Change on the Shores of Lake Erie : A History of the United States District Court for the Northern District of Ohio, Paul Finkelman and Roberta Sue Alexander, eds., (Ohio: Ohio University Press, 2012), 112-113. ↵

- “All about Eugene V. Debs, Who Once Fought US Presidential Election from Prison,” Hindustan Times (New Delhi, India), August 26, 2023. ↵

- Ernest Freeberg, Democracy’s Prisoner : Eugene V. Debs, the Great War, and the Right to Dissent (New York: Harvard University Press, 2010), 250. ↵

- Ernest Freeberg, Democracy’s Prisoner : Eugene V. Debs, the Great War, and the Right to Dissent (New York: Harvard University Press, 2010), 205. ↵

- Ernest Freeberg, Democracy’s Prisoner : Eugene V. Debs, the Great War, and the Right to Dissent (New York: Harvard University Press, 2010), 206-207. ↵

- Ernest Freeberg, Democracy’s Prisoner : Eugene V. Debs, the Great War, and the Right to Dissent (New York: Harvard University Press, 2010), 257-258. ↵

- Melvin I. Urofsky, “Chapter 4: The Trial of Eugene V. Debs, 1918,” Justice and Legal Change on the Shores of Lake Erie : A History of the United States District Court for the Northern District of Ohio, Paul Finkelman and Roberta Sue Alexander, eds., (Ohio: Ohio University Press, 2012), 115. ↵

- Melvin I. Urofsky, “Chapter 4: The Trial of Eugene V. Debs, 1918,” Justice and Legal Change on the Shores of Lake Erie : A History of the United States District Court for the Northern District of Ohio, Paul Finkelman and Roberta Sue Alexander, eds., (Ohio: Ohio University Press, 2012), 115. ↵

23 comments

Jordan Robbins

Hi, through your writing I learned so much about someone I’ve never heard of! His story is so encouraging and tragic but shows you can do anything you put your mind to. I like the initial photo you put at the beginning; its so clear! What made you decide to study his story?

Silvia Benavides

Amazing work in writing and bringing light to this aspect of political history.

Gaitan Martinez

Never heard of this man named Debs; but nonetheless, his story was very interesting and inspiring. I honestly couldn’t have done what he did, even though the US government was infringing on his first amendment, I wouldn’t take the chance of destroying my life because of it. However, one could argue that’s how many governments get away with stories like this because no one wants to step up.

Mariana Chamorro

Your article on Eugene V. Debs offers a captivating glimpse into a transformative period in American history. The clear storytelling and inclusion of historical context make the narrative both accessible and engaging. It’s a fascinating read that leaves a lasting impression. Great work!

Carlos Anthony Alonzo

Impressive work! Your study on Eugene Debs is a testament to your scholarly dedication and rigor. The innovative approach you’ve taken sheds new light on her story, prompting further exploration. Your article hold significant implications for both the historical significance. I look forward to seeing how your research continues to develop!

Lauren Sahadi

This was a crazy story. Eugene V. Debs’ journey from presidential candidate to federal prisoner and back again was a very interesting story that drew me into the article. Debs remained strong in his beliefs and gained support. This was very inspirational and shows what can happen when you advocate for social justice. I really enjoyed reading this article, great job.

Stela Naomi Sifuentes

This article highlighted how a dream couldn’t be stopped with actual barriers. Debs’ presidential campaigns were a beacon of hope for the marginalized and oppressed. His impassioned speeches and tireless efforts to challenge the status quo left an indelible mark on American politics, paving the way for future progressive movements.

Mariana Mata

I distinctly remember learning about Eugene Debs in APUSH back in high school, but I never knew his story this explicitly.

It is interesting to see how the U.S. government dealt with different political opinions, most of them being punished, to then being seen as heroes or changemakers in American society. This can also be said about the people involved in the civil rights movement, and even today.

Sebastian Hernandez-Soihit

Great article and a sobering reminder of the often forgotten legacy of organized socialism in the united states. I probably last head of this person in my junior year of high school and it’s definitely thought provoking what would have occurred in the United States if the socialist party saw more success.

Nicholas Pigott

Hi Jacqueline! This article is by far one of the most interesting political history articles I have read, and your choice of topic was fantastic. Eugene Debs is simply a fascinating character, and it’s so interesting how the idea of socialism was handled before a time where it was nothing more than a word to scare people. Congratulations on your nomination!