In 1858, Abraham Lincoln watched the nation plummeting deep down the division between the North and South. The Kansas-Nebraska Act in 1854 already ignited multiple political conflicts and debates. The Dred Scott decision earlier in 1857 added fuel to an already burning flame. The Union’s survival was under attack, and the future of America was seemingly vague. The territories were about to be in a massive clash, and Lincoln knew it would not end pretty. That was when he chose to get involved in this heightened discord and address the core problem of it all: slavery. With the Illinois Republican convention coming up in June 1858, he knew he would have to speak out. As Lincoln crafted his soon-to-be-known “House Divided” speech, one thing was certain: “a house divided against itself cannot stand.”1

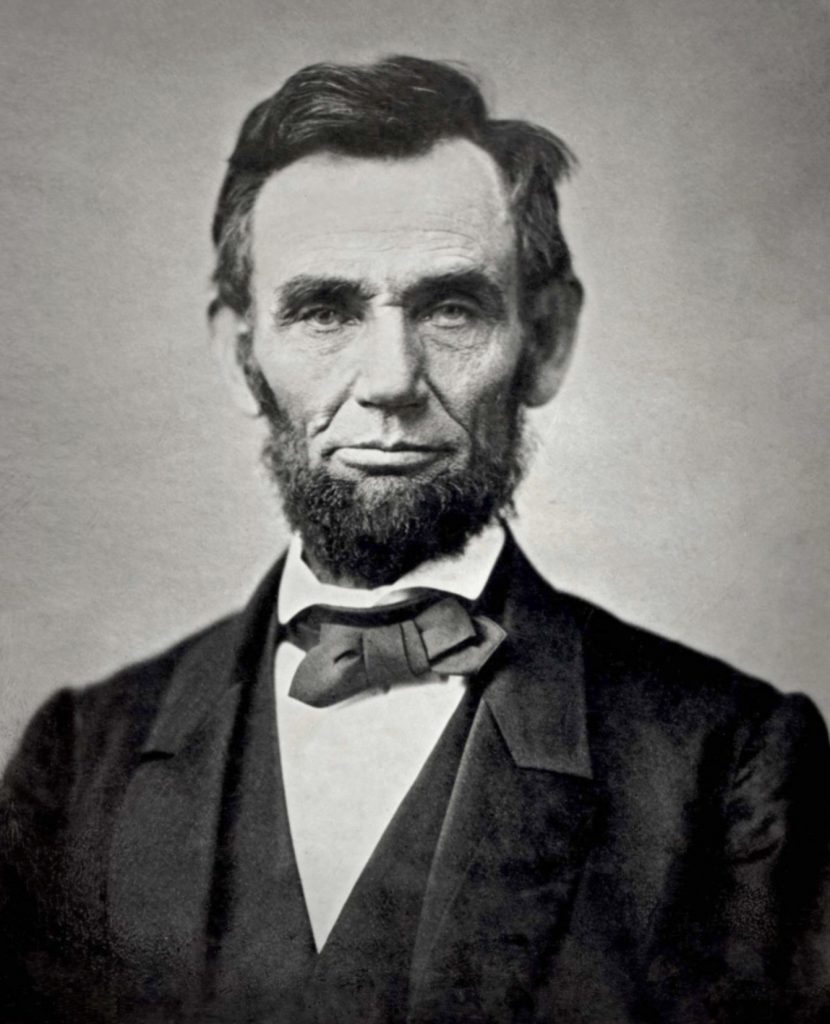

Lincoln was always ahead of his time in his social and political views. Though he was born in Kentucky, a slave state, most of his upbringing and career were in Indiana and Illinois, free states, which limited his exposure to slavery. While skimming down the water on a boat full of produce on the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers to New Orleans in 1831 with his friend, he encountered something that turned him against slavery. It was the sight of dozens of humans being sold as slaves in the New Orleans slave market. The encounter shocked him as well as widened his horizon. He wrote years later that the sight was a continental torment to him: “And I see something like it every time I touch the Ohio or any other slave-boarder.”2

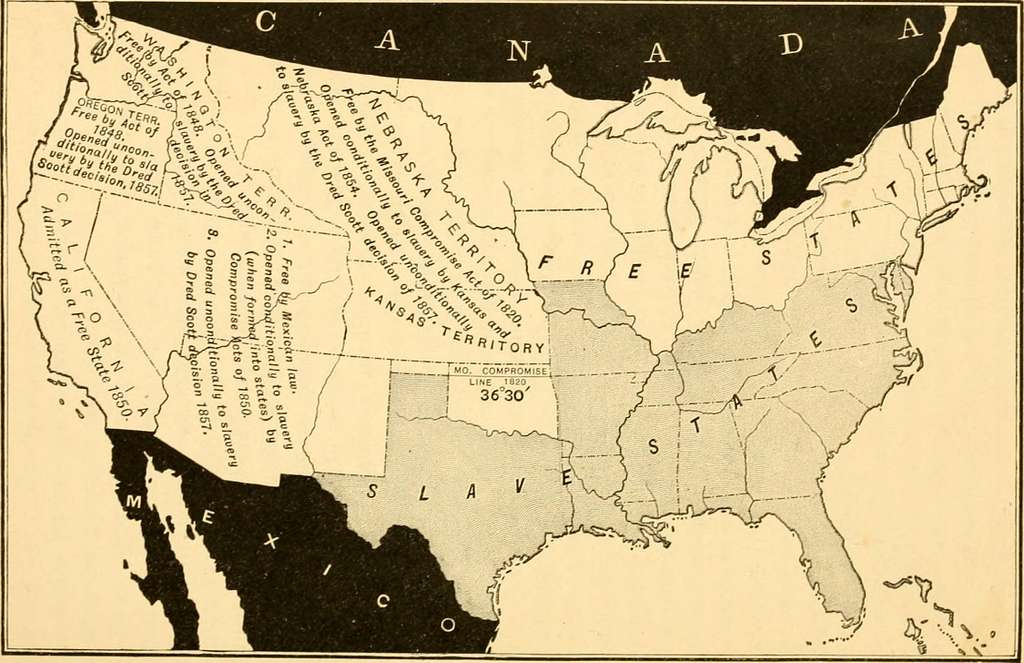

The Missouri Compromise of 1820 had tried to contain the pressure between the North and South by maintaining the balance between slaves and free states by banning slavery in the Louisiana Territory north of latitude 36º30′ with the exception of Missouri itself. Then, in 1850, another compromise was made due to the continuously rising tensions on both sides regarding slavery. Within the compromise, aside from admitting California as a free state into the Union, as well as letting Utah and New Mexico territories use popular sovereignty to decide on slavery, a stricter Fugitive Slave Act was formed. The slave owners were given the power to recapture runaway slaves who escaped to other free states, potentially turning everyone into slave catchers. The act also criminalized assisting the escape of slaves, resulting in a substantial fine and imprisonment if anyone were to be discovered helping a runaway slave. Finally, the Fugitive Slave Act was ex post facto–meaning it would apply to all slaves including those who had escaped before the act was in power. Though the government did not exactly get rid of slavery, Lincoln was at ease a little bit as people accepted the act wholeheartedly and stopped the country from its tipping point of going into a civil war. On the death of Henry Clay in 1852, Lincoln praised him as “a man with moderation and humanitarianism” for his creation of the 1850 Compromise but also pointed at him for being a slave owner. Clay opposed slavery based “on principle and feelings” rather than how it could have been once eradicated. Lincoln also stigmatized the abolitionists and Southerners who would rather “burn the last copy of the Bible” or “tear to tatters its now venerated constitution,” denying the assertion in the Declaration of Independence that “all men are created equal,” rather than letting slavery exist for a single hour.3

When Words Became Weapons: Lincoln’s Fight to Unite a Fractured America

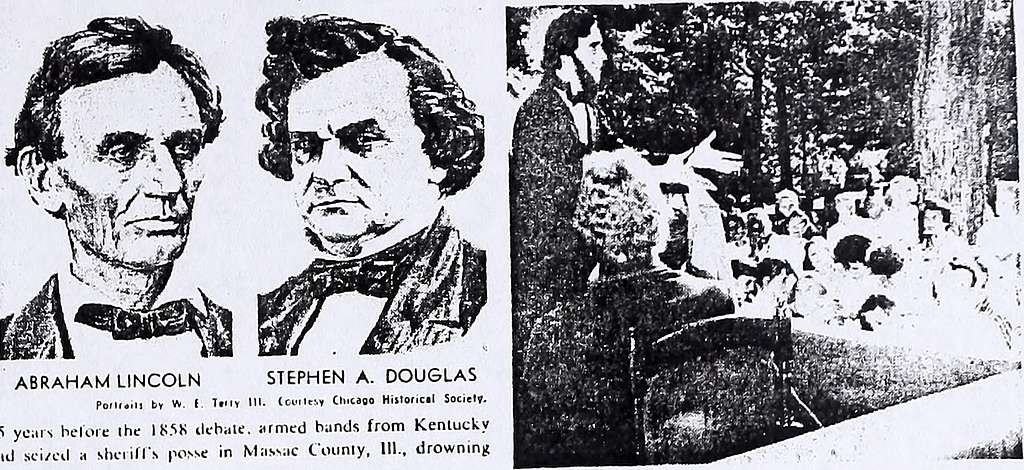

In 1854, Abraham Lincoln returned to politics after taking a break from it since 1849, and it was all because of one act that pushed him to the edge: the Kansas-Nebraska Act. The act was proposed by Senator Stephen A. Douglas, granting all states and territories to permit slavery or ban it on their own, using the principle of “popular sovereignty” as they had used in Utah and New Mexico after the Mexican-American War. Even though it appeared to be a means for states to enjoy freedom of choice, the act nullified the Missouri Compromise previously introduced, potentially spreading slavery to unwanted new territories. It all started in 1852 when an organization bill for the new Nebraska territory was passed with heavy Southern opposition. Nebraska was well above the 36º30′ latitude, so slavery would be prohibited there. However, to encourage everyone to move to this new territory, the Senator of Kentucky, Archibald Dixon, pointed out that everyone including the Southerners and slave owners should have a chance to move there, and by doing that, he suggested to Senator Douglas that the restriction of the compromise must be repealed. Douglas was shocked to hear this, yet agreed and validated Dixon’s idea later on when the Kansas-Nebraska Act was presented on January 23, 1854.4

As predicted by Senator Douglas, it raised “a hell of a storm.” Indignations among Northerners, including Lincoln himself, were everywhere; antislavery Democrats denounced Douglas’s bill as “a gross violation of a sacred pledge,” “as a criminal betrayal of precious rights,” and “as part and parcel of an atrocious plot.”5 After the passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act, parties began to split and chaos emerged. Northern Democrats withdrew from their party. The Whig party was also divided along sectional lines, although they were better maintained in the Northern states. The nation was becoming more and more divisive and Lincoln could witness it.6

Reentering politics in 1854 after the passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act, Lincoln had no hope of a new political career. His initial motivation was to help the re-election of Richard Yates of Jacksonville as a representative of the Seventh Congressional District of Illinois, who opposed the Nebraska bill. In late August, Lincoln took on behalf of Yates to rally the Whig forces by agreeing to run for State Legislature. While pondering immensely on the slavery issue, Abraham Lincoln studied multiple books in the state’s library, learning from debates in Congress and writing down memoranda as he toured the Congressional district on Yates’s behalf. He found within himself a new power, a sense of responsibility, and promises as he delivered multiple speeches, attracting more attention to his growing concern about the expansion of slavery. He soon received invitations to speak outside the district. Meanwhile, Senator Stephen A. Douglas returned to Illinois to defend his stance on introducing the Kansas-Nebraska bill. He met opposition and ugly public hostility everywhere he went; people confronted him, especially in Chicago.7

Antagonism only provoked Douglas’s spirit more. On October 3, 1854, a state fair opened in Springfield. Douglas gave a speech to win back people’s faith in him during a rainy day in the House of Representatives. Lincoln attended the speech to see his reasoning for the Nebraska bill. Douglas’s speech focused on Western development and the issues it brought to the nation. He reviewed the history of the Missouri Compromise and claimed his efforts to extend the Compromise line to the Pacific were blocked by Northern Whigs, Free-Soilers, and abolitionists. He argued that the Compromise of 1850 replaced the geographical boundary between slave and free states with the principle of popular sovereignty used in Utah and New Mexico, which he then applied to Kansas-Nebraska. He denied that he intended to expand slavery, arguing it couldn’t thrive there due to the region’s soil and climate. Twelve days later, in Peoria, Illinois, Lincoln prepared a speech in response to Douglas. He criticized the Kansas-Nebraska Act as a betrayal of this principle, as it opened new territories to slavery. Lincoln voiced his moral opposition to slavery, seeing it as unjust and harmful to America’s democratic image. He believed in self-government and argued that true self-government could not justify enslaving others. Instead, he called for a return to the ideals of the Declaration of Independence, urging unity among Whigs, Free-Soilers, and abolitionists to restore the Missouri Compromise and resist slavery’s expansion.8

In the October elections, Democrats lost significant ground, with thirty-one Congressional seats lost in Pennsylvania, Ohio, and Indiana, while the Know-Nothings party gained in New England. In Illinois, Democrats won only four out of nine Congressional seats. The newly elected Illinois Legislature, which will soon elect a new U.S. senator, comprised forty-one Democrats and fifty-nine members of various anti-Nebraska groups. Though Yates narrowly lost his Congressional seat, Lincoln was elected to the Legislature.9

Before this, the conflicts culminated in the forming of a new party that same year in 1854 called the “Republican Party,” comprising primarily former members of the Whig Party, anti-slavery Democrats, Free-Soilers, abolitionists, and other anti-slavery advocates. Their objective was to resist the expansion of slavery and restore the Missouri Compromise. Among the anti-Nebraska abolitionists were the Know-Nothings.10 Though opposing slavery, they were also against Catholicism and immigrants. Their bigotry alienated them from the rest of the abolitionists, making it hard for the antislavery movement to unite under a complete party. In the summer of 1855, some of Lincoln’s abolitionist friends suggested the statewide antislavery convention. However, Lincoln opposed the idea as the political atmosphere was heightened, potentially resulting in offending any other party, especially the nativists of the Know-Nothings. He and others still hoped that the Whig party would be a viable foundation for the antislavery movement to continue since their presence in the presidential election in 1848 and 1852 with around 43% and 42% of the popular vote respectively, and nine seats in the U.S. House of Representatives. Yet aside from that, many others wanted to form a new party to reunite all antislavery supporters.11 Shortly after the 1855 election, antislavery newspapermen attempted to unify the parties. The Pike County Press endorsed forming a new, united party; more than twenty papers followed. On January 10, 1855, an antislavery meeting was held in Decatur, Illinois; only around twelve journalists made it to the meeting due to a severe storm (the number was suspected to be more than fifty). Lincoln attended the gathering as an informal guest. During the meeting, the abolitionists were delighted at the decline in pro-slavery. They assured that they would eventually defuse the threat from the nativists. On May 29, 1856, in Bloomington, a Republican Convention was held. Lincoln delivered an enticing speech that journalists had to drop their pencils and listen to; only two brief newspapers had records of it. People referred to it as the “lost speech,” as journalists were so enchanted by Lincoln’s delivery of the speech. Nonetheless, Lincoln effectively launched the Illinois Republican Party under his eminent leadership.

On March 6, 1857, another tragic event urged the Republicans to take action against slavery. The Supreme Court was examining the case of Dred Scott, an enslaved black man who was determined once he had entered a free state, he would free himself. After the case, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that Congress had no power to prohibit slavery and that black people were not American citizens. In June 1857, Lincoln denounced the court decision in Springfield, Illinois. Two weeks earlier, Douglas addressed the decision as final from the higher authority and that going against it was a deadly blow to the Republican government system as well as calling Republicans’ criticism as promoting amalgamation between the races. Lincoln forcefully protested against that statement Douglas made. “I protest against that counterfeit logic which concludes that, because I do not want a black woman for a slave I must necessarily want her for a wife. I need not have her for either, I can just leave her alone. In some respects she certainly is not my equal; but in her natural right to eat the bread she earns with her own hands without asking leave of anyone else, she is my equal, and the equal of all others,” said Lincoln. In closing his argument, Abraham Lincoln affirmed the difference between the two parties: The Republican party accepted the black man’s identity and that knowing his bondage was morally wrong; The Democratic Party denied the Declaration of Independence, wrongful bondage of the black men, and cultivate hatred and disgust within them.12

In the same year of 1857, when Kansas applied for statehood, a pro-slavery minority dominated the constitutional convention in Lecompton, Kansas. Despite the territory being very unrepresentative of the majority of the settlers’ opinion, President James Buchanan urged Congress to admit it as a slave state. Misrepresenting the idea of popular sovereignty, Douglas felt supporting the Lecompton Constitution would go against his chance for reelection in 1858. He denounced the president’s choice to which even some Illinois Republicans applauded him and considered backing him for reelection. Douglas met with Horace Greeley, an editor of the renowned New York Tribune to further spread his cause. Greeley wrote to John O. Johnson, secretary of the Illinois Republican State Central Committee, urging him to back Douglas. Other papers in the East supported Greeley idea’s that the Republicans should support Douglas. Prominent New England Republicans like Henry Wilson, Anson Burlingame, and Truman Smith sided with it too. However, the senator later denied affiliation with the Republican Party, only mentioning that he had severed his ties with the Democrats. The obvious opponent against Douglas, Abraham Lincoln, suggested the abolitionists keep their heads high. Douglas may be using his chance to woo the support of Republicans solely to get reelected as senator for the upcoming election of 1858. In December 1857, he also made an angry speech warning Republicans not to aid Douglas and reminded them about the racist points he had made about slavery before.13Lincoln was right that the Republican Party had been battling Douglas for far too long. Some abolitionists might admire his stance against the Lecompton Constitution, but opposing him was the greatest bond that tied the party together in the first place. Lincoln regarded it as a threat to the Republican integrity.14

In April 1858, the Democratic State Convention in Illinois endorsed Douglas as a candidate for reelection to the Senate seat as an anti-Lecompton Democrat. They pressed the Republican Party to make no nominations against him as well as to trust and support him as the new antislavery leader.15 The Republicans were indeed reluctant to back Douglas, and most of them agreed that Douglas was not a good fit for their cause. However, one thing they could not deny was their nomination for Lincoln to be the Republican candidate for the election, setting a scheme for the campaign.

From the 7th to the 16th of June, Abraham Lincoln was meticulously engaged in writing a speech– a speech he would soon give for the upcoming Republican Convention of Illinois on the 16th. On the 13th, Mr. Dubois, the State Auditor, entered Lincoln’s office and noticed a man concentrated on writing. He asked Lincoln what it was about, and the Republican just ignored him, saying it was none of his business. He wrote and scraped, and wrote again, a sentence now and another. It was scattered in numberless pieces of paper, which, in the end, was reduced to a few sheets that Lincoln hoped would nominate him for the senator position in Congress. One evening, Lincoln came early to his office and invited Mr. William H. Hernon, a close abolitionist friend who had been helping for the past year in the Republican Party. Carefully locking the door behind him, he pulled out a manuscript from his bosom, and proceeded to read to Hernon slowly and distinctly. After finishing the first paragraph, Lincoln asked for his opinion. “I think,” replied Hernon, “it is true; but it is entirely politic to read or speak it as it is written?” “That makes no difference,” said Lincoln. “That expression was a truth to all human experience, ‘a house divided against itself cannot stand;’ and ‘he that runs may read.'” Hernon thought it was a risk to take such a radical view during the political clash in the country. He knew that the strange doctrine would alienate him from the voters. The only thing Lincoln cared about was spreading the truth, foregoing a trial of experiment, announcing a starling theory, and upholding the values the party was based on. Hernon also could not stop him, as Lincoln liked to tell the truth without caring for consequences. It would soon have to be either a silent or an acknowledgment moment. He urged Lincoln to read it as it was written. Later, around a dozen men were called to enter the State House’s Library Room. After being seated at a round table, John Armstrong, one of them, read that clause of the section where Lincoln would to the others. He slowly read and quoted “A house divided against itself cannot stand.” They all agreed that the speech was spirited yet too far away in advance in time. They condemned that part of the speech as unwise and impolitic, even false. Disagreeing after listening to their respective opinions, Hernon stood up, saying the speech was true, political, and wise. “Nay it will aid you, if it will not make you President of the United States,” exclaimed Hernon. Lincoln sat still for a moment, then stood up saying that the time has come whether it is right or wrong, “‘a house divided against itself cannot stand,’ I say it again and again.”16

Finally, the day came. On June 16, 1858, the Republican delegates flooded the Hall of Representatives in Springfield. Amid the bussling convention, the Chicago delegation brought a banner that read “Cook County for Abraham Lincoln,” resulting in loud shouts and applause. Lincoln! Lincoln! Lincoln! was the cry everywhere. Delegates from Chicago, Cairo, Wabash, and all of Illinois were filled with enthusiasm. This was a special occasion as state parties did not usually endorse a candidate for Senate before the election of the legislature, which would decide who would fill that post.17

That day, Lincoln stood before the crowd, addressing them while reading his script. He delivered the speech slowly and carefully. He started by addressing Douglas’s rebellion against President Buchanan and the Lecompton Constitution, which may have rendered him an attractive opponent of slavery, yet, it was superficial for him to be the party’s vote based on their basic principles. Then, he began by paraphrasing Daniel Webster’s speech, emphasizing the importance of understanding the current situation before making decisions. Lincoln proceeded to address the Kansas-Nebraska Act failing to end slavery agitation, which only increased. Lincoln predicted this agitation would continue until a crisis was reached. “Such agitation will not cease, will not cease, until a crisis shall have been reached, and passed.”

“That was inevitable,” he said, “because ‘a house divided against itself cannot stand,’ as Jesus had long ago warned.” “I believe this government cannot endure, permanently half slave, half free. I do not expect the Union to be dissolved—I do not expect the house to fall—but I do expect it will cease to be divided. It will become all one thing, or all the other. Either the opponents of slavery will arrest the further spread of it, and place it where the public mind shall rest in the belief that it is in the course of ultimate extinction; or its advocates will push it forward, till it shall become alike lawful in all the States, old as well as new—North as well as South.”18

After addressing the future, he then pointed out suspension in the past. Lincoln argued that a conspiracy to expand slavery had been pursued over the past four years, with key events including first the Kansas-Nebraska Act (1854) opening all states to slavery; secondly, the election of James Buchanan (1856) who endorsed the idea of popular sovereignty, and finally the Dred Scott decision (1857) (suspiciously two days later, the justices handed down their decision that black people are not citizens and that Congress could not prohibit slavery from entering new territories). He suspected that these events were part of a coordinated plan to expand slavery and warned that the Supreme Court might soon rule that states could not exclude slavery. Lincoln believed that the power of the political dynasty needed to be met and overthrown to prevent this from happening. Reaching his main point, Lincoln argued that opponents of the slave power must resist Douglas’s overtures. He asserted that Douglas, despite his resistance to the Lecompton Constitution, was not the best instrument to thwart slavery expansionists. Lincoln noted that Douglas’s supporters reminded him of his greatness, then conceded the point with a quote that said “A living dog is better than a dead lion” and maintained that though Douglas was not a deceased one, he is, in fact, a “caged” and “toothless” one. Republicans must rely on their members to continue their fight against slavery, as Douglas has abandoned their cause. Despite facing challenges, Lincoln assured the party had successfully endured and would eventually triumph.19

The Republican press in Illinois regarded Lincoln’s speech as “able, logical, and most eloquent.” The Burlington Free Press in Vermont praised it as “sound doctrine, lucid statements, clear distinctions, and apt illustrations.”20 William Hernon applauded Lincoln for his bravery in speaking out. The speech made a profound impression on all men. The Democrats triumphed and reprobated it, while the Republicans received it coldly, accepting it as a defeat for the party-a fatal error that no policy or exertion could retrieve.21 It was expected that the Republican Party would feel that the doctrine was too extreme. A slow cautious man like Lincoln carrying such a bold statement could dismay his followers, assuring victory for the enemies.

A day or two after the speech, Dr. Long rushed into his office, giving him feedback on the statement. “Well, Lincoln,” said Dr. Long, “that foolish speech of yours will kill you, will defeat you in this contest, and probably for all offices for all time to come.” “I am sorry, sorry, very sorry, I wish it was wiped out of existence,” replied Lincoln. “Don’t you wish it, now?” Long expressed. Lincoln was writing during Dr. Long’s rant, and he finally stood up, laid his pen down, raised his spectacles, and responded. “Well, doctor, if I had to draw a pen across, and erase my whole life from existence, and I had one poor gift or choice left, as to what I should save from the wreck, I should choose that speech and leave it to the world unerased.” Some, like Leonard Swett in Illinois, regarded the sentiment of “house divided against itself ” was inappropriate, the wrong thing, the abstract truth, however, standing by the speech, he felt some factual statements of it, “I was inclined at the time to believe these words were hastily and inconsiderately uttered; but subsequent facts have convinced me they were deliberate and had been matured…”22 John Locke Scripps told Lincoln that the opening of his speech was too ultra to the Kentuckians. Lincoln’s “House Divided” speech was misinterpreted by some Kentuckians as an abolitionist call to war against slavery, leading to accusations of “ultraism” during his campaign. Lincoln denied these claims, asserting his intention was not to interfere with slavery in existing states.23

Later during the campaign, Lincoln challenged Douglas in a series of joint debates. The Senator was reluctant to accept the invitation as there was nothing to gain; it was only for Lincoln to spread his view to the public. In the end, Douglas agreed and the two men met in seven three-hour debates across Ottawa, Freeport, Jonesboro, Charleston, Galesburg, Quincy, and Alton, in that order. Between debates, each man spoke almost daily for four months to large crowds in the open air, traveling incessantly between engagements by railroad, steamboat, or horse and buggy, enduring poor food and accommodations in country inns, and never missing a single engagement. Ten thousand people showed up to the Ottawa debate, listening for three hours under the blazing sun. Fifteen thousand were at Freeport, watching under the chilly drizzle. An estimated twelve to fifteen thousand at Charleston. Around five or six thousand in smaller towns. Each candidate had a shorthand reporter to record the proceedings. Speeches and debates were widely published from special correspondents’ reports; some papers printed all or part of the debates.24

In one debate, Douglas asked Lincoln why couldn’t the country survive as a half-free half-slave as it had for seventy years. Lincoln explained the “ultimate extinction” would drive the South into secession. Douglas also admonished Lincoln’s alleged belief in “negro equality,” sensing a winning issue in Illinois where racist sentiments were strong. Douglas shouted to the crowd: “Are you in favor of conferring upon the negro the rights and privileges of citizenships?” Back the answer “No, no!” “Do you desire to turn this beautiful state into a free negro colony in order that when Missouri abolishes slavery she can send one hundred thousand emancipated slaves into Illinois, to become citizens and voters on an equality with yourself?” “Never, no!” The crowd shouted again. “If you desire them to vote with on an equality with yourselves… then support Mr. Lincoln and the Black Republican party, who are in favor of the citizenship of the negro. (‘Never, never!”)” Lincoln was forced to take a defensive stance. He pleaded that he was not in favor of bringing equality for the white and black race, but instead the morality of bondage itself. It was slavery that would continue to be the issue of the country but the citizens were silent about it. To enslave one was already a morally wrong action. “The problem with Douglas was that he looks to no end of the institution of slavery, while the Republicans will, if possible, place it where the public mind shall rest in the belief that it is in the course of ultimate extinction, in God’s good time.”25

The election ultimately came to an end with Republican and Democrat popular vote for the legislators almost even on November 2, 1858. However, the inequitable apportionment law was still in place. The Senate was fourteen Democrats to eleven Republicans; and in the House, forty Democrats to thirty-five Republicans. Stephen A. Douglas, unsurprisingly, got reelected as Senator.26 Lincoln was bitterly disappointed and continued to speak for the Republican candidates in the following years. Nevertheless, Lincoln gained enough recognition around the country for his bold stance that paved the way to become the first Republican president in 1860.

It was no doubt that Abraham Lincoln was one of the greatest debaters in American history. He kept his temper while maintaining clear answers and was never afraid to speak the truth despite the likely collapse of his political career. The story of his “House Divided” speech is an example of government interference in a society’s morality where people were enabled to do immoral things such as enslaving others. It was the government’s job to address the issue directly, ensuring justice and equality. Unfortunately, in this story, Lincoln’s time had not come yet.

- James M. McPherson, Abraham Lincoln (New York : Oxford University Press, 2009), 19. ↵

- James M. McPherson, Abraham Lincoln (New York : Oxford University Press, 2009), 4. ↵

- Michael Burlingame and Benjamin P. Thomas, Abraham Lincoln: A Biography (Southern Illinois University Press, 2008), 132. ↵

- Michael Burlingame and Benjamin P. Thomas, Abraham Lincoln: A Biography (Southern Illinois University Press, 2008), 139. ↵

- Michael Burlingame and Benjamin P. Thomas, Abraham Lincoln: A Biography (Southern Illinois University Press, 2008), 139. ↵

- Michael Burlingame and Benjamin P. Thomas, Abraham Lincoln: A Biography (Southern Illinois University Press, 2008), 144. ↵

- Michael Burlingame and Benjamin P. Thomas, Abraham Lincoln: A Biography (Southern Illinois University Press, 2008), 146-147. ↵

- Michael Burlingame and Benjamin P. Thomas, Abraham Lincoln: A Biography (Southern Illinois University Press, 2008), 147-151. ↵

- Michael Burlingame and Benjamin P. Thomas, Abraham Lincoln: A Biography (Southern Illinois University Press, 2008), 152-153. ↵

- Michael Burlingame and Benjamin P. Thomas, Abraham Lincoln: A Biography (Southern Illinois University Press, 2008), 152. ↵

- Michael Burlingame, Abraham Lincoln : A Life (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012), 407-408. ↵

- Michael Burlingame, Abraham Lincoln : A Life (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012), 438-440. ↵

- Michael Burlingame, Abraham Lincoln : A Life (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012), 445-447. ↵

- Michael Burlingame and Benjamin P. Thomas, Abraham Lincoln: A Biography (Southern Illinois University Press, 2008), 178. ↵

- Ward Hill Lamon, The Life of Abraham Lincoln; From His Birth to His Inauguration As President (Lincoln: Bison Books, 1999), 395. ↵

- Ward Hill Lamon, The Life of Abraham Lincoln; From His Birth to His Inauguration As President (Lincoln: Bison Books, 1999), 397-399. ↵

- Michael Burlingame, Abraham Lincoln : A Life (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012), 458. ↵

- Michael Burlingame, Abraham Lincoln: A Life, vol. 00001, Abraham Lincoln (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012), 459. ↵

- Michael Burlingame, Abraham Lincoln : A Life (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012), 459-460. ↵

- Michael Burlingame, Abraham Lincoln : A Life (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012), 465. ↵

- Ward Hill Lamon, The Life of Abraham Lincoln; From His Birth to His Inauguration As President (Lincoln: Bison Books, 1999), 406. ↵

- Ward Hill Lamon, The Life of Abraham Lincoln; From His Birth to His Inauguration As President (Lincoln: Bison Books, 1999), 406-407. ↵

- Michael Burlingame, Abraham Lincoln : A Life (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012), 466. ↵

- Michael Burlingame and Benjamin P. Thomas, Abraham Lincoln: A Biography (Southern Illinois University Press, 2008), 184. ↵

- James M. McPherson, Abraham Lincoln (Oxford ; New York : Oxford University Press, 2009), 19. ↵

- Ward Hill Lamon, The Life of Abraham Lincoln; From His Birth to His Inauguration As President (Lincoln: Bison Books, 1999), 419. ↵