Background:

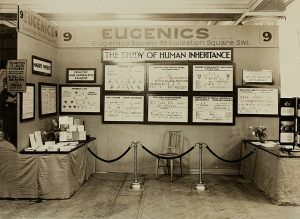

The field of genetic counseling has transformed since it first started in the late 1800s. Since genetic counseling was established in the eugenics era of the country, the basis implies that the first clients in genetic counseling were not people particularly interested in genetics, but people identified by the state as needing regulation of citizenship. It wasn’t until the second phase of genetics in the late 1930s and through the 1960s that it diverged from the eugenics movement to academic and medical implications 1

During current times, genetic counseling is used as an informative pathway regarding reproductive decisions, as well as a scientific premise to identify genetic markers for certain hereditary conditions such as cancer, cystic fibrosis and Huntington’s disease.

Genome and genomic applications have not only allowed the identification of disease-causing genes but have also made possible the understanding of the disease’s heritability patterns. In addition, the availability of such technology has allowed patients with suspicion of carrying a genetic disease with the option of receiving genetic counseling.

Even though the profession of genetic counseling has seemed versatile in the scientific field due to its various implications, it has three main goals: informing patients and families about genetic risk, providing information about test options and interpretations of results, and assisting decision-making and adaptation to loss. However, these implications have revolutionized medicine due to the need to reconcile ethical principles to an excessively diverse network of values and principles within patients. Such a challenge preoccupies genetic counseling in disproportion because it involves divisive discussions about reproductive choices, the impact on learning disabilities, and the impact on people’s lifestyles. In other words, genetic counseling creates an ethical framework around when and to what limit is acceptable for counselors to make testing and other recommendations to patients 2.

Beyond debating recommendations and the delivery of results to patients, genetic counseling has raised concerns in the field of medicine regarding its limitations to certain socioeconomic statuses. This challenge is often highlighted in discussions about resource allocation within the healthcare system and the ethical implications of access being limited to patients with specific ethnic backgrounds and financial means. Additionally, genetic testing—a byproduct of genetic counseling—brings attention to an ongoing concern: the patients’ right to keep their information private and how feasible this is with current technology.

Genetic Counseling as a Key Driver of Scientific Advancement and Genomic Technology Enhancement.

Data Collection and Research Contributions:

Even though they are often thought to be limited to prenatal testing, genetic counselors work through all life stages. This includes preconception, prenatal diagnosis, newborn diagnosis, elderly diagnosis, and predisposition to diseases at any stage 3. In addition, this profession not only guides the patient’s decisions over various conflicts such as adapting to new lifestyles, but they are experts with the ability to translate complex terminology into a language that a patient understands. This skill is extremely important, as diagnosis related to risks or diseases necessitates genetic testing. Genetic testing for both risks and diagnosis is the basis of genetic counseling and a patient must understand the process before they decide to participate in it.

As a result of genetic counseling, the genetic testing results of consenting patients are crucial for the advancement of science in understanding heritability patterns, disease-causing genes, mutations, family histories, etc. It is estimated that about 75% of genetic counselors are involved in educating physicians, nurses, etc., occupying positions as research coordinators for genetic research studies.

Cancer research has been identified as one of the most rapidly increasing subdisciplines of genetic counseling. Counselors have determined that to address heritable patterns for most cancers, information from at least three generations must be collected and analyzed in a pedigree. This information has given light to understanding family histories and the impact of environmental factors for differential diagnosis of various cancers such as hereditary breast-ovarian cancer syndrome, HBOC 4. Currently, we are able to understand the role of mutations in the BRCA1 and BRCA 2 genes, and how patients with these mutations are most likely to develop HBOC.

Enhancing Genetic Testing Technologies:

Besides understanding and interpreting data, genetic counselors play a significant role in enhancing new genetic testing technologies. As the number of patients being tested for genetic disorders increases, the volume of sequencing information also grows. By adopting technologies such as next-generation sequencing (NGS), multidisciplinary teams in the health professions are conducting extensive catalogs of gene panels, transcriptomics, epigenetics, and genotyping assays for genetic disorders. These technologies have also led to guidelines that regulate genetic interpretations, such as those from the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG). The ACMG includes representatives from the Association for Molecular Pathology (AMP) and the College of American Pathologists (CAP), and together, they revise standards for the interpretation of sequence variants 5. Collaborations like the ACMG allow for the identification of new regulations in managing patient data, consequently driving innovation and advancements in genetic technologies.

Genetic Counseling and Its Risks: Health Benefits Discrimination, Data Misinterpretation, and Threats to Patient Privacy

Limited Access Inequities

As previously discussed, genetic counseling has the potential for early detection and diagnosis of multiple genetic disorders. However, it has been identified that minorities, for the most part, are unable to access these services. This challenge not only raises ethical concerns regarding equity in health rights but also impacts the data interpretation process 6

Among some of the reasons why minorities do not participate in genetic services are limited access—often due to a lack of awareness of these services—geographical location, socioeconomic factors, and mistrust of the healthcare system concerning genetic information. This last factor has been identified as the most common reason for the low involvement of minorities in genetic testing, even after the passage of the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (GINA) in 2008. GINA was designed specifically to help protect Americans from discrimination by employers and insurance companies based on their predisposition to or possession of genetic disorders 7. According to a survey conducted among African Americans, mistrust in the healthcare system primarily prevails due to previous experiences with medical attention and historical racial discrimination. Responses such as “To be used in some type of experiment and then be forgotten” and “Why are you interested in me now?” were among the most common reactions from African American minorities asked to participate in research studies 8.

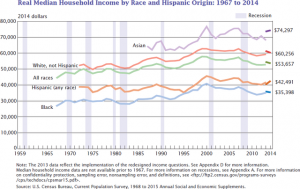

In addition to limited access to genetic counseling in minority groups raising ethical considerations for the field, an additional challenge for its practice arises. With the limited participation of certain ethnic groups in research studies, genetic databases result in a skewed population distribution, with accessible data mostly limited to European-descendant patients. As a result, the credibility of applying such data to minority ethnicities is significantly decreased. For example, it is estimated that the majority of African Americans experience the highest rate of receiving an inconclusive result for a variant of unknown significance (VUS) when undergoing BRCA1 or BRCA2 genetic testing. Approximately 5.5% of American women of European descent receive a VUS result, compared to African American women, who receive a positive VUS 45.5% of the time. This implies that even if African American women have been identified as having a mutation in the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes, whether it increases their risk of developing HBOC or not cannot be determined 9.

Current Genomic Legislation:

The usage of genetic counseling services and their genetic testing implications also raises concerns about data accessibility and how this impacts patients’ privacy. The digitalization of the healthcare system, the creation of genetic databases, and new biotechnological tools for data interpretation imply concerns for users due to the constantly changing privacy laws. As technology advances, so does the legislative code regarding regulations on digitalized data, and the ability of companies to secure patients’ privacy often seems compromised. Such challenges have led to the development of privacy laws such as the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA). This act was developed specifically to seek solutions to privacy concerns that were previously completely absent from formal contemporary law 10. However, none of the proposed solutions by HIPAA to protect digital data have been strictly applied in the healthcare system.

Health professionals and social workers have identified that the main emerging concern regarding how genetic data is managed is directly related to the creation of new genealogical databases and mobile health apps. None of the information accessed through these platforms falls under the jurisdiction of the Department of Health and Human Services, the Office for Civil Rights, or even HIPAA regulations. It is recognized that none of the complaints made regarding patients’ information shared on these platforms are validated, as there is currently no law governing this data. Studies have shown that although some of these complaints could potentially be addressed by the Federal Trade Commission, the majority of consumers are not even aware that their data is being collected, as there is no formal notification to acknowledge the sharing of consumers’ information, whether for profit or not 11.

Conclusion

The field of genetic counseling and genomics is a complex network between advantageous scientific advancements and inevitable ethical concerns. While it is clear that this discipline has been crucial in enhancing the understanding of lethal diseases like cancer, the validity of opposing viewpoints cannot be dismissed. Throughout this article, it has been clearly stated that genetic counseling is a crucial societal tool that has been advantageous to science. Its progress is appreciated and valued, especially by those directly involved in the scientific community.

However, the lack of comprehensive protections for patient privacy is profoundly concerning. This vulnerability places current society in challenging ethical situations, such as empowering the racial discrimination that has been a part of our history. While the value of this field is recognized when implemented correctly, there are significant dangers arise if it continues to operate with insufficient regulations, as evidenced by the absence of formal legislation regarding consumer data protection.

The ample opportunity for improvement within the healthcare system and the field of genetic counseling should focus not only on the training of professionals but also the education of minority populations, particularly in light of the exponentially growing technological advancements. Additionally, a primary focus should be the development of a legislative framework that not only restricts third-party access to genetic data but also establishes mandatory consumer consent for data use. Although this may prove challenging, setting smaller, achievable goals in the field could lead to more rapid and meaningful change.

These goals should include enhancing education about the purposes of genetic research, the testing process, and its consequences, targeting both patients and healthcare professionals. It is crucial that patients, particularly those from minority ethnic backgrounds, receive comprehensive education about the possibilities of genetic counseling and testing. This education should cover not only how genetic information could impact their life and reproductive decisions but also how it can be a valuable tool for enhancing their lifespan. Patients should feel assured that a professional will be with them throughout the process, from diagnosis to testing, and even in cases where adaptations may be needed. Concurrently, professionals must be continuously trained to communicate this information sensitively, considering the diverse ethnic and cultural backgrounds of patients. This approach is essential for rebuilding the trust that has been fractured within the healthcare system, particularly in the discipline of clinical research.

- LeRoy, Bonnie. Prescribing Our Future: Ethical Challenges in Genetic Counseling. Routledge, 2020 ↵

- Jamal, Leila, Will Schupmann, and Benjamin E. Berkman. “An Ethical Framework for Genetic Counseling in the Genomic Era.” Journal of Genetic Counseling 29, no. 5 (2020): 718–27 ↵

- Bennett, Robin L., Heather L. Hampel, Jessica B. Mandell, and Joan H. Marks. “Genetic Counselors: Translating Genomic Science into Clinical Practice.” The Journal of Clinical Investigation 112, no. 9 (November 1, 2003): 1274–79 ↵

- Bennett, Robin L., Heather L. Hampel, Jessica B. Mandell, and Joan H. Marks. “Genetic Counselors: Translating Genomic Science into Clinical Practice.” The Journal of Clinical Investigation 112, no. 9 (November 1, 2003): 1274–79 ↵

- Richards, Sue, Nazneen Aziz, Sherri Bale, David Bick, Soma Das, Julie Gastier-Foster, Wayne W. Grody, et al. “Standards and Guidelines for the Interpretation of Sequence Variants: A Joint Consensus Recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology.” Genetics in Medicine: Official Journal of the American College of Medical Genetics 17, no. 5 (May 2015): 405–24 ↵

- Richards, Sue, Nazneen Aziz, Sherri Bale, David Bick, Soma Das, Julie Gastier-Foster, Wayne W. Grody, et al. “Standards and Guidelines for the Interpretation of Sequence Variants: A Joint Consensus Recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology.” Genetics in Medicine: Official Journal of the American College of Medical Genetics 17, no. 5 (May 2015): 405–24 ↵

- Saulsberry, Kalyn, and Sharon F. Terry. “The Need to Build Trust: A Perspective on Disparities in Genetic Testing.” Genetic Testing and Molecular Biomarkers 17, no. 9 (September 2013): 647–48 ↵

- Br, Kennedy, Mathis Cc, and Woods Ak. “African Americans and Their Distrust of the Health Care System: Healthcare for Diverse Populations.” Journal of Cultural Diversity 14, no. 2 (Summer 2007) ↵

- Br, Kennedy, Mathis Cc, and Woods Ak. “African Americans and Their Distrust of the Health Care System: Healthcare for Diverse Populations.” Journal of Cultural Diversity 14, no. 2 (Summer 2007) ↵

- Theodos, Kim, and Scott Sittig. “Health Information Privacy Laws in the Digital Age: HIPAA Doesn’t Apply.” Perspectives in Health Information Management 18, no. Winter (December 7, 2020): 11 ↵

- Theodos, Kim, and Scott Sittig. “Health Information Privacy Laws in the Digital Age: HIPAA Doesn’t Apply.” Perspectives in Health Information Management 18, no. Winter (December 7, 2020): 11 ↵