The Day of the Dead, also known as Día de los Muertos, is more than just a holiday for many belonging to the Mexican heritage. It is a profound symbol of love, a way of remembering, and a ceremonial occasion embodying an implicit belief in the afterlife. Vibrant altars, offerings, and festivals presuppose a strong connection between the living and the dead. Inquiring into the meaning of this presupposition, this article showcases the philosophical research process through the stages of inquiry, outlining and drafting a response by theorists about what the implications of a living community tradition are by examining artworks that are representative of life-death transition in conjunction with established theories of personal identity, or the soul. Whether there is an afterlife is not so much presupposed by this inquiry. Rather, by asking what the connection between the living and the departed may consist of, the question of what constitutes a soul is answered in transformative terms of mind, matter, and medicine. This research project builds on taking into consideration contrasting views of materialism and dualism, the cultural significance of the Day of the Dead, and the Stoic philosophy of Epictetus, Gonzalez-Crussi’s clinical and celebratory account of the Day of the Dead.1 While the Western tradition in philosophy offers competing accounts of the soul, the artwork speaks to no matter of proof of an afterlife, but the fact there is meaning in life, the inevitability of death, and the imperative to embrace the present. Philosophers must define the soul by formulating a hypothesis to a certain extent before they can further explore the idea of an afterlife. It is useful to use modern methods that examine our material culture and the concepts of past philosophers who contribute more to the picture to address such a weighted question. Thus, the theory of the soul is examined through the Stoic philosophy of Epictetus, while taking into consideration the contrasting views of materialism and dualism, artistic attempts to interpret the relations and the cultural and clinical significance of the Day of the Dead. Some new views are available with examples from the San Antonio Museum of Art, alters, and the Float seen on its Riverwalk. These viewpoints demonstrate different routes philosophers and artists have taken to answer these questions, and the role of art in shaping ideologies on life, death, human connections, and what comes after life.

Seen at the Day of the Dead River Parade, San Antonio, 2024, this image captures a vibrant Día de los Muertos (Day of the Dead) celebration in San Antonio, featuring a colorful, illuminated parade float on a river with skeleton-themed decorations and performers dressed in traditional calavera (skull) attire. The scene is set against a festive backdrop with lively lights, murals, and a decorated bridge, creating a visually striking nighttime display.

Epictetus and How to Judge the Soul

Rather than give every view of the soul, it may help to look at one where the body and soul can be taken together and regarding how a person can form art from life. Epictetus, who wrote a book translated as Art of Living: The Classical Manual on Virtue, Happiness, and Effectiveness, offers a profound perspective on the soul, emphasizing its connection to reason and virtue. Now there is an assumption that an individual’s soul would not be tangible, nor could it be harmed by outside events.2 But something crucial to think of while reading the Philosophy of Epictetus is that humans pass judgment during their lives. Epictetus believed that the soul is the source of moral agency and decisions, not just an abstract idea. The soul is the core of our being, responsible for our ability to make judgments and choices that reflect our moral character. The soul can exercise these judgments and make decisions that align with the virtue and fulfillment that is within everyone.

Judgment is a power of reason and is thought to be something that makes humans distinct from other beings. Precisely because we have reason, they can be substantially more reflective, which is why, for Epictetus, it must be connected to the soul. Though this process can be altered by external events, Epictetus is not discussing the event itself but the internal interpretation that created the response. A reflective response can be anything such as categorizing things, or distinguishing good from bad and yet deeper, on the matter of staying in line with virtue. Similar to the idea of freedom of mind over body. There must be a rational agency that holds such profound weight for reason and “…it is enough that logic has the power to analyse and distinguish other things…”, which emphasizes the soul’s true nature of external events.3

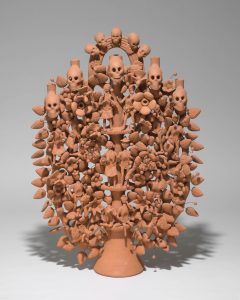

Epictetus does not specifically express a new interpretation of a soul; however, Epictetus presents a framework where moral virtue depends on the soul’s ability to govern itself. If humans did not have a soul, then there would be no judgment or reason for the actions humans make. This means that without this intangible concept, there would be no moral development and no ethical behavior during life. Epictetus understands how important this is to have, which is why he writes “for if it is true that all error is voluntary and you have learnt the truth, you must do rightly hereafter”, to imply that the reason humans use and actions they take while living have lasting significance.4 This reinforces the concept that once the truth is known, the soul is fully accountable for its mistakes and choices. It can also be viewed that accountability is a type of moral preparation as it receives judgment in death. That is why the soul must align with truth or virtue so it can fulfill its purpose and prepare for life beyond death. The Tree of Death is an example of the Tree of Life popular art tradition where the central theme is death imagery associated with the Day of the Dead. Trees of life with death imagery may be placed on Day of the Dead altars to memorialize loved ones.

Based on Epictetus’s theory of the soul, it is balanced in nature. But after Descartes, philosophers could take up two distinct types of views, which are incompatible, materialist and dualist. Materialists align with this naturalistic theory of the afterlife much more readily as they believe that the soul is not independent of the body. In most cases, the possibility of an afterlife is rejected since the soul and body are connected, and with the death of the body, the soul would not necessarily persist or leave the body as well as conscious life if it is part of the body. However, now there are more possibilities to consider. In an article categorizing views on the “Afterlife” so far, Hasker provides a different take from the materialist view of the afterlife, and that is the soul’s resurrection. Materialists view the afterlife not as a spiritual continuation but as the resurrection of the body itself, which aligns more closely with materialist views than with dualist interpretations of the soul. This may seem surprising, but it could show a lot that is going on in the material world, including artistic interpretations. Hasker identifies this as “one possible reason for thinking that materialism is not hostile to the prospects of an afterlife… in the major theistic traditions is that it involves the resurrection of bodies”, which could be a possibility of survival.5

Even with this agreement, materialism still must deal with the fundamental problem of identity. How can the resurrected body be the same as the deceased if there is no material soul to endure death? Bridging the time difference between the resurrected body and the dying body is an obstacle. Hasker responds to this problem by stating that “…nothing bridges the spatio-temporal gap between the body that perishes and that body resurrected…” and without a continuous, immaterial soul, the materialist theory struggles to explain how personal identity is preserved across the span of death.6 Personal identity could be duplicated if humans assume divine power is present, however, Hasker points out that “if God could create one body that is exactly similar to the body that died, why not two or more?”.7 This kind of situation poses the important questions of what makes a soul, what it is, and whether physical recreation is sufficient to preserve the core of an individual’s identity in death.

These challenges prompt consideration of a different viewpoint that is dualism. The issue of identity and continuity in the afterlife may be considered by dualists, which, in contrast to materialists, emphasizes a clear separation between the body and the soul. This means that if the soul is independent of the body once it dies, then the immaterial soul has a chance to live. This way of thinking suggests that the personal identity itself is sourced from the soul. The body would be the housing for the soul and when it dies the soul would need to go somewhere. Based on Hasker’s work, there is no guarantee of this possibility of survival for the soul because “it may be that the functional dependence of ourselves on our bodies is so essential that we only come into existence as embodied persons”.8 If the identity is so tightly connected to the body, then perhaps there will be an unforeseeable change in its death.

With this dualist perspective, there is stronger proof for the soul to live on after the body decomposes. The challenge is that what exactly occurs to the soul itself is something that dualists are not sure of. Hasker argues that “we cannot make judgments about the identity of souls, because souls are said to be imperceptible and non-spatial”, which makes it more difficult to confirm the continuity.9 Disembodied souls over time may have changes similar to humans of the living, as opposed to the physical body, which can be observed and re-identified. The dualist perspective offers a possibility for survival beyond bodily death, but it faces challenging ideas regarding the coherence of such survival and what that would be defined as. Dualism offers a framework that makes the survival of the soul after death possible.

An afterlife is made possible by the idea of a disembodied soul, but it demands more assumptions about the nature of this existence, such as how the soul might see or interact in a non-physical condition. Hasker identifies multiple possibilities and dualists suggest that such concerns often turn into metaphysical and epistemological issues, emphasizing that “there is no problem that needs a solution” when it comes to understanding the persistence of a soul.10 Considering these difficulties, dualism is still a viable option to explain the afterlife since it offers a continuity of identity beyond death. This lays the groundwork for thinking about how different frameworks approach the issue of human life and survival. Hasker is not a materialist or dualist and cannot provide a clear answer to whether there is an afterlife after deep explanations of multiple views. However, Hasker provides the necessary structure of thoughts and beliefs for those who are searching for an answer. What he can conclude is that the answer to the question is highly based on one’s perspective during their present life.

Philosophy in Correspondence: Princess Elisabeth’s Objections to Descartes

Princess Elisabeth of Bohemia raised crucial objections to René Descartes’ dualism, particularly concerning the interaction itself between the soul and body. In her correspondence with Descartes, she questioned “how the soul of a human being can determine the bodily spirits, in order to bring about voluntary actions”, and vice versa.11 She found it difficult to comprehend how an intangible thing could alter the physical body. As these two entities are separate, Descartes identifies that they do interact with each other and should be seen as a union. This is particularly due to the function of the soul as it “…is conceived only by the pure understanding…”, and this allows humans to have reason as moral agents.12 However, this cannot be acted upon alone, it requires “the body, that is [an] …extension, shapes, and motions”, something material.13

Elisabeth then argued that all known causal interactions require a shared contact, impossible between the immaterial and material that Descartes made separate. Descartes’ response illustrates there is a small part of the physical body that must allow the soul to exercise its functions. He suggested that the mind and body interact through the pineal gland.14 Though his theory, at the time, was not scientifically plausible, this prompted a need for further response to Elisabeth. He acknowledged his response was insufficient and more in-depth questions that came afterward and further shaped future debates in the philosophy of the soul by demanding a more coherent account of soul-body interaction.

Medicine, and the Art of Living

This is why there must be some outside perspective to all of this, and it can be seen through medicine. Gonzalez-Crussi had an extensive career in pathology and understands death on the biological level. He has seen death frequently and knows that death is a biological certainty. He describes this career as not only to “encounter …the phenomenon of termination of life”, but “this is the pathologist, whose task, in effect, has just begun”.15 According to Gonzalez-Crussi, pathologists “both confront the dead and the body’s interior”, so they see what type of emotion evolves around this profession.16 Through this, he has learned that being a pathologist is a symbol of healers being defeated and is in a constant state of exploring what makes life and death. But what he has also seen is people’s reaction to death in Western traditions. Humans often do not know how to grieve, which is why medicine is in demand. Medicine is considered a form of art. Humans use art to express their emotions, and “art is uniquely efficacious in stirring the wonderment and respect that are the dues we owe to death”.17 Gonzalez-Crussi realizes that everyday physicians’ job is to prevent the inevitable. Medicines focus on extending life shows avoidance and is ultimately a metaphor to make sense of death.

Gonzalez-Crussi traveled to Mexico during the annual tradition of the Day of the Dead. This is when he was able to see such a difference in views on death. In Mexican ancient cultures, “earth and death are…intertwined in the religion of the ancient Aztecs”, so it was not surprising to see such embracement around death.18 There was all the traditional decor around, but what fascinated him was how excited people were. They were excited for souls to come to earth and celebrate what their life was. Gonzalez-Crussi was not sure of the idea of a soul with all of his time in the medical field. Through his travels, it became clear that the ideas associated with death were not scary for people in Mexico because they understood the inevitable. They used tradition and belief that helped with their emotions. They celebrated the souls of those they loved. Medicine might fail to bring about emotional closure in Western traditions, however, his experience in Mexico showed him how death can be respectfully, humbly, and warmly included into existence in this celebration. Gonzalez-Crussi argues that though death is inevitable, it can be expressed in a healthier manner through cultures. The Day of the Dead provides a positive acceptance of mortality. Having access to personal stories, medical insights, and art in different forms creates ways that the living can express and process through the natural fear of death. Through this people can have more meaningful lives despite the inevitable end.

Through exploring the philosophical inquiry on the afterlife, there must be a deeper understanding of the soul. Identifying the theory of the soul opens the possibilities to its connection to life, death, and what could be plausible afterward. Epictetus allows for a theory that there is a soul due to its responsibility for moral agency, reason, and accountability. This allows humans to have significant virtues and a truthful life. Materialists believe in the conjunction of the body and soul and ponders if there is an afterlife, would it be continuous for the soul or lose its identity as a living being? Dualism offers a unique perspective on the independence of the soul from the body, and it also allows for the possibility of the survival of the soul since it does not perish when the body does.19

Transformative Emotion: From Grief to Joy on the Day of the Dead

Aesthetic practices surrounding grief serve far more than decorative or ceremonial functions; they play a vital role in helping individuals process and navigate the emotion of loss. Higgins describes these practices as a way of “stabilizing the grieving person’s impressions, expressing strong emotions, facilitating reflection, providing resources for orienting oneself and guidance for moving forward…”.20 Through pictures, objects, or rituals, aesthetic immersion gives those grieving a way to place themselves within their loss, offering a space for reflection and a way to express sympathy and remembrance. Grief can be felt, seen, and shared through these techniques, which ground abstract emotions in tangible forms rather than being simply about beauty or death.

Limiting our view of these practices to beauty alone would, as Higgins warns, “restrict the topic unduly” and draw attention away from their deeper practical and symbolic uses for grief and mourning, which can be seen as the focal point in Western aesthetics without acknowledgment of the good to come.21 Instead, they provide those grieving to hold onto the ways they want to remember the deceased. This not only creates comfort in the moment but also is a “…remind[er] of all the good things they have given…and build on their non-material legacies in a spirit of gratitude”.22 Grieving and mourning loved ones is devastating because where there was once joy, there is a new emotional void. Thus, creating these aesthetic opportunities of remembrance allows one to move forward with purpose.

Conclusion: The Art of Living and the Afterlife

These philosophical views must be able to be analyzed in everyday emotions such as those that come with death. And the best way to do so is to look at the art of celebrating an afterlife. Día de los Muertos celebrates mortality with respect and satisfaction, in contrast to Western customs that frequently view death with sorrow. The belief in the soul and an afterlife can influence attitudes toward death and offer emotional closure, as seen by this cultural tradition. The underappreciative celebration of life and death restricts those from remembering the joy that was necessary to turn into grief. The idea of the soul connects the living and the dead. Through Epictetus’ moral framework, the contrasting views of Hasker, or Gonzalez-Crussi’s clinical and celebratory experience with the Day of the Dead, the soul remains in the conversation.23 They all remind people that no matter the proof of an afterlife, there is meaning in life. Instead of worrying about the inevitable death, humans must embrace the present as it may prepare them for what comes next.

- Epictetus. Discourses, Books 1 and 2. Translated by P. E. Matheson. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1916, and F. Gonzalez-Crussi. The Day of the Dead: And Other Mortal Reflections. New York: Harcourt Brace and Co., 1993. ↵

- Epictetus. Discourses, Books 1 and 2. Translated by P. E. Matheson. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1916. ↵

- Epictetus. Discourses, Books 1 and 2. Translated by P. E. Matheson. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1916, page 35. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- William Hasker and Charles Taliaferro. “Afterlife.” In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2023 Edition), edited by Edward N. Zalta and Uri Nodelman. ↵

- William Hasker and Charles Taliaferro. “Afterlife.” In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2023 Edition), edited by Edward N. Zalta and Uri Nodelman, part 3. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- William Hasker and Charles Taliaferro. “Afterlife.” In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2023 Edition), edited by Edward N. Zalta and Uri Nodelman, part 2. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Lisa Shapiro. Correspondence Between Princess Elisabeth of Bohemia and René Descartes. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007, page 62/661. ↵

- Lisa Shapiro. Correspondence Between Princess Elisabeth of Bohemia and René Descartes. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007, page 69/692. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Lisa Shapiro. Correspondence Between Princess Elisabeth of Bohemia and René Descartes. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007. ↵

- F. Gonzalez-Crussi. The Day of the Dead: And Other Mortal Reflections. New York: Harcourt Brace and Co., 1993, page 4. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- F. Gonzalez-Crussi. The Day of the Dead: And Other Mortal Reflections. New York: Harcourt Brace and Co., 1993, page 172. ↵

- F. Gonzalez-Crussi. The Day of the Dead: And Other Mortal Reflections. New York: Harcourt Brace and Co., 1993, page 44. ↵

- Epictetus. Discourses, Books 1 and 2. Translated by P. E. Matheson. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1916. and William Hasker and Charles Taliaferro. “Afterlife.” In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2023 Edition), edited by Edward N. Zalta and Uri Nodelman. ↵

- Kathleen Marie Higgins. Aesthetics in Grief and Mourning: Philosophical Reflections on Coping with Loss. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press, 2024, page 3. ↵

- Kathleen Marie Higgins. Aesthetics in Grief and Mourning: Philosophical Reflections on Coping with Loss. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press, 2024, page 3. ↵

- Kathleen Marie Higgins. Aesthetics in Grief and Mourning: Philosophical Reflections on Coping with Loss. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press, 2024, page 171. ↵

- Epictetus. Discourses, Books 1 and 2. Translated by P. E. Matheson. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1916, and William Hasker and Charles Taliaferro. “Afterlife.” In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2023 Edition), edited by Edward N. Zalta and Uri Nodelman, and F. Gonzalez-Crussi. The Day of the Dead: And Other Mortal Reflections. New York: Harcourt Brace and Co., 1993. ↵