Introduction

Domestic violence within the Latino community has long been a pressing issue in the United States, yet research on this topic remains outdated. According to the National Violence Against Women Survey (NVAWS), one in four Latinas has experienced domestic violence at some point in their lifetime (Tjaden & Thoennes, 2000). However, recently, the National Latina Network reported that about 1 in 3 Latinas (34.4%) will experience intimate partner violence in their lifetime, and 1 in 12 Latinas have experienced IPV in the past 12 months (National Domestic Violence Hotline n.d.). Despite evidence suggesting that domestic violence is widespread in the Latino community, it is often perceived as a private marital or familial matter rather than a serious social issue with significant individual and public health consequences (Flores-Ortiz, 2004; Lewis, West, Bautista, Greenberg, & Done-Perez, 2005). Additionally, traditional cultural norms—particularly those emphasizing male dominance—may make it difficult for Latinas to recognize and address the problem. This study uses the Crime, Health, and Intimate Partner Problems Survey (CHIPPS), a cross-sectional survey conducted at St. Mary’s University, to explore how such factors may be prevalent among a college population. As a Hispanic Serving Institution, the students were asked to provide their ethnicity so that a comparison between race/ethnicity may be examined. As a preliminary study of the CHIPPS (data collection ongoing), the present study seeks to add to this critical literature by addressing such serious public health issues among a college population, with many students being the first in their families to attend an institute for higher education.

Partner Violence and the Latino Community

Several factors have shaped our understanding of domestic violence in the Latino community. Women between the ages of 24 and 45—particularly during pregnancy and the postpartum period—are at a heightened risk of experiencing domestic violence (Rapp-Paglicci et al., 2002). Despite ongoing discussions about the causes of domestic violence in Latino communities, there is no consensus on a singular definition. Definitions vary, but according to the Handbook of Violence, cultural traditions and social patterns have been used to explain violence against women within both society and the family unit.

Historically, Latin American societies have been influenced by two key social principles: (a) hierarchical structures in which some individuals give orders while others serve, and (b) the belief that specific individuals, in this case women, are inferior and, therefore, expected to obey (Rapp-Paglicci et al., 2002). From an early age, boys are socialized into firm gender roles, learning that as men, they will assume the roles of leader, provider, and authority figure within the household, creating a “machismo” mindset. In Latin America, conversations about machismo often focus on gender relations, including its links to toxic masculinity, sexism, and gender-based violence (Atske, 2024). Many cultures continue to uphold the belief that women are inherently subordinate to men, reinforcing male dominance and shaping traditional gender norms. Latina identities are often defined by their roles as mothers and wives, and the Latino patriarchy denies women individuality based on gender. Those who do not conform to these traditional ideals are labeled as “mala mujer” (bad woman) (Flake & Forste, 2006). Authoritarian structures contribute to the ideologies of Mexican American culture. These characteristics can foster an environment where men feel justified in asserting dominance over their wives, increasing the likelihood of domestic abuse (Kantor et al., 1994).

In the United States, it is estimated that one in six women experiences abuse from their intimate partners, and 22% of adult women report having been physically assaulted by a partner. National surveys conducted throughout the late 1990s yielded mixed results due to variation in sample size, region, and study context. Additionally, researchers studying domestic violence within Latino communities face several obstacles, including fear of deportation, economic and emotional dependence on a partner, and limited access to information about federal, state, and community resources (Rapp-Paglicci et al., 2002).

Religious Families are not immune to the frequency, severity, or long-term consequences of abuse. When violence occurs in homes, religious women often feel vulnerable, believing their abusive partner can and will change (Nason-Clark et al., 2018). In Latin American society, women are usually expected to embrace the reverence of the Virgin Mary, symbolizing their ability to endure suffering, particularly concerning male authority. They are traditionally expected to be submissive, dependent, and sexually faithful to their husbands, dedicating themselves to their families (Flake & Forste, 2006). They are reluctant to seek outside resources and less likely to leave temporarily or forever. Many times, women feel disappointed by the response of their religious leaders to their call for help. Often believing they were called by God to endure this suffering, to forgive (or keep forgiving) their abusive partner, and continue fulfilling their marital vows for better or for worse until death do us part (Nason-Clark et al., 2018).

Little is known about the role that religious faith plays in the lives of men who have acted abusively against an intimate partner. Studies report mixed findings about the relationship between religious faith and intimate partner violence/ abuse perpetration. A study exploring the perceptions of Latino men involved in a parish-based partner abuse intervention program reported past misuse of religion to gain control over their intimate partners (Davis and Jonson-Reid, 2020).

When analyzing Latino families, social scientists highlight two key concepts: familism and machismo. Familism refers to the cultural emphasis on prioritizing immediate family over their interests, while machismo characterizes Latino masculinity, often associated with aggressive and hypersexual behaviors. Although these two concepts may seem contradictory, they coexist within Latino family structures. The intersection of familism and machismo can create an environment where women are more vulnerable to domestic violence, as they are expected to fulfill familial obligations unconditionally within a patriarchal framework (Flake & Forste, 2006). Men teach their sons how to be the “man of the house,” the head of the household, and how to demand certain behaviors from their partners (Quiroga 2024). A study found that many immigrant Latina survivors initially believed the abuse they experienced was a “normal” part of marriage. Only after migrating to the U.S. did they realize that a life without abuse was possible (Latinas and Intimate Partner Violence: Evidence-Based Facts).

Socioeconomic and Demographic Factors

For many Latina women who rely on their husbands, leaving an abusive relationship is often difficult due to economic dependence. Financial concerns and lack of formal education among Latinas have been identified as significant barriers to seeking support and developing sustainable livelihoods. Economic sabotage, such as an abuser interfering with their partner’s employment, has been documented as a tactic of control. A study reported abusive strategies such as workplace surveillance, harassment, and job disruption (Kantor et al., 1994). Unique tactics used against Latinas include denying access to a driver’s license, lying about childcare arrangements, and temporarily sending the partner to their country of origin (Latinas and Intimate Partner Violence: Evidence-Based Facts).

When examining socioeconomic factors, there are several reasons to consider a higher prevalence of domestic violence among Hispanic families. In 1991, it was reported that the median income of Hispanic families was 65% of that earned by non-Hispanic families, with over a quarter of Hispanic families living below the poverty line (Kantor et al., 1994). According to the U.S. Census Bureau, in 2023, the poverty rate for Hispanic individuals in the United States was 16.6%. Between 2022 and 2023, the official poverty rate decreased for White and non-Hispanic White individuals, while the only group to experience a statistically significant increase was the Two or More Races population (Shrider, 2024).

When immigrating to the United States, some Hispanics undergo acculturation, the process in which an immigrant group adopts the norms and behaviors of the host society. This process can cause prolonged stress, alienation from Mexican culture, and discrimination within Anglo-American society (Kantor et al., 1994). Acculturation has been the focus of multiple studies investigating how adapting to cultural norms in the U.S. relates to immigrant Latinas’ experiences of intimate partner violence (IPV). Studies suggest that IPV is less prevalent among those with strong ties to traditional Latino cultural values (Latinas and Intimate Partner Violence: Evidence-Based Facts). One study found that among diverse sexual minority women, those with a household income of more than $50,000 reported fewer instances of severe IPV compared to those with an income of less than $10,000. Additionally, Black and Latina sexual minority participants reported higher rates of severe IPV than White women (Latinas and Intimate Partner Violence: Evidence-Based Facts).

Alcohol

The relationship between alcohol and domestic violence is complex. While research widely supports a correlation between alcohol consumption and violent behavior, there is little consensus on the precise role alcohol plays in partner violence. Some scholars argue that this relationship varies depending on the drinking context, the individuals involved, and the nature of the perpetrator-victim relationship (Flake & Forste, 2006). Given these complexities, a comprehensive theoretical framework must incorporate multiple factors to explain the link between alcohol and violence effectively.

One promising explanation is selective disinhibition theory, which suggests that alcohol impairs perception and judgment, interacting with a range of social and psychological factors that may contribute to violent behavior in certain situations. This understanding is fundamental in Latin America, where gender norms often encourage heavy alcohol consumption among men (Flake & Forste, 2006). In Latino culture, excessive drinking is relatively common, and the failure to acknowledge alcohol-related problems can lead to social pressure to engage in drinking, increasing the likelihood of harmful consequences.

Beyond selective disinhibition theory, researchers have proposed additional explanations for the connection between alcohol and violence. Alcohol myopia theory posits that intoxicated individuals experience a narrowed focus, like a camera lens, which limits their perception of broader social cues. This restricted view can lead to misinterpretations, such as perceiving an accidental bump in a bar as a hostile act. Similarly, cognitive function impairment theory highlights how alcohol disrupts problem-solving abilities, emotional regulation, and decision-making, all of which influence how an individual responds to conflict. Finally, research suggests that individuals who prioritize immediate gratification over long-term consequences are more likely to exhibit aggressive behavior while intoxicated (Martens, 2022).

Witnessing Domestic Violence

Although many women worldwide experience DV (Garcia-Moreno et al., 2006), the silent and invisible victims are the children living with them, whose significant adverse effects of childhood exposure to DV are frequently overlooked (Shorey and Baladram, 2024). It is estimated that about 15.5 million children and youth are exposed to domestic violence every year. A study examining over 1,500 police reports of DV in a Northeastern United States community found that 22% of Latino children and youth reported having witnessed DV in the past year. Exposure to DV can look different for families; children and youth may directly witness violence between their caregivers, they may hear it, or they may witness the aftermath, bruises, and other marks of abuse. Children and youth may even be asked to participate in the abuse of a parent (e.g., to report actions and whereabouts of a caregiver to the other caregiver) (Latin@ Children and Youth Exposed to Domestic Violence 2021). Numerous studies have identified a link between witnessing domestic violence and the intergenerational transmission of violence. Observational learning, as explained by social learning theory, suggests that children who witness violence, especially when it is rewarded, may adopt both violent behaviors and positive attitudes toward aggression. Consequently, children exposed to such violence may develop destructive conflict resolution and communication patterns, increasing their likelihood of engaging in aggressive behavior later in life (Murrell et al., 2007).

In the late 1990s, scholars proposed that the intergenerational transmission of family aggression involves both generalized and specific modeling—the acceptance of aggression within families and the enactment of types of aggression observed in childhood (Murrell et al., 2007). Psychological, physical, and social consequences of exposure to DV are seen across ages, cultures, and socioeconomic backgrounds (Latin@ Children and Youth Exposed to Domestic Violence 2021). Studies indicate that 46% of preschool-aged Latino children exposed to IPV exhibit PTSD symptoms, including distress at reminders of the event, repetition of traumatic statements, reenactment of the incident, and heightened arousal (Quiroga 3). Infants who witness DV have been found to show symptoms related to PTSD, such as trouble sleeping, refusing to eat, and having trouble keeping food down (Latin@ Children and Youth Exposed to Domestic Violence 2021). Adolescents who witness abuse may develop maladaptive behaviors: boys are more likely to engage in physical aggression, while girls are more likely to withdraw and experience depression. Exposure to violence also increases the likelihood of delinquent behaviors, such as skipping school and substance use (Quiroga 3). Socialization and modeling play key roles in reinforcing gender roles. Fathers and male role models may not explicitly instruct their sons to be physically abusive. Still, they may strengthen misogynistic ideologies—such as the belief that women manipulate and control their partners, necessitating male dominance. This learned perception can contribute to abusive behavior in future generations.

Researchers have found some evidence of the impact of DV on parent-child relationships. Caregivers directly receiving violence are likely to experience higher levels of stress and poorer mental health outcomes, which in turn have been found to impact caregivers’ full potential to engage in effective parenting practices. DV exposure is also associated with diminished quality of caregiver-child relationships. In addition, DV exposure in childhood predicted poor parent-child attachment with both mothers and fathers in adolescence. DV may create a context in which the abused parent’s physical and emotional availability to the child is jeopardized. This, in turn, undermines the child’s sense of trust in the caregiver’s capacity to provide support and protection (Latin@ Children and Youth Exposed to Domestic Violence 2021).

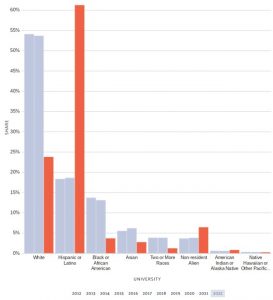

This research examines whether the intergenerational transmission of violence and aggression persists specifically within Latino families, as they represent the fastest-growing ethnic minority in the United States, particularly in Texas. San Antonio, Texas, the eighth-largest U.S. city, has a significant Mexican-origin population (Romo, 2008) of 64.4% according to a 2023 U.S. Census Bureau (U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: San Antonio City, Texas, 2023), making it an essential area for studying transnational families (Romo, 2008). As a Hispanic-serving institution, St. Mary’s University reflects these demographics, with Hispanic or Latino students comprising most of its enrollment.

Hypothesis

Based on these findings, the following hypotheses are proposed.

H1: Religious attitudes promoting traditional gender roles will positively affect IPV.

H2: Low self-control will be positively associated with IPV.

H3: Alcohol use will be positively associated with IPV.

Methods

Data

The experimental data come from the Crime, Health, and Intimate Partner Problems Survey (CHIPPS), a cross-sectional probability sample of St. Mary’s University undergraduate students (n = 453), which was designed to analyze differences in partner violence and religious views on gender roles in the home. Students were randomly chosen via their student email. The survey was then emailed so participants could complete it on their computer or mobile device. Respondents were offered a $10 gift card to participate in the survey. Data was collected from April 2024 through April 2025.

Analytical Strategy

Materials used in this research included the statistical software program R to compile and sort the data before exporting it to RStudio. Access to the data was provided by Dr. Colton L. Daniels, who created the CHIPPS survey. Negative binomial regression was used across four models due to the outcome variable’s variance being greater than its mean. All analyses were conducted in R.

Measures

Outcome Variable

Intimate partner violence was measured using the conflict tactics scales revision (CTS2) (Straus et al. 1996). The trauma ascertained from this scale encompasses (a) psychological violence, (b) physical assault, and (c) sexual assault. The CTS2 has been used to assess partner violence in over 20 societies and continues to gain acceptance among respected international organizations (Garcia-Moreno et al. 2006). All items were reversed-coded, so 0 = never happened, 1 = once in the past year or not in the past year, but it did happen before, 2 = twice in the past year, 3 = 3 to 5 times in the past year, 4 = 6 to 10 times in the past year, 5 = 11 to 12 times in the past year, and 6 = more than 20 times in the past year. Then, using the midpoint method constructed by Straus et al. (1996), the items were summed into a cumulative variable with higher values representing a higher frequency of experiencing partner violence.

The frequency of prayer was gauged using an ordinal question. This question asked, “How often do you meditate or pray by yourself?” The answers ranged from “More than once a day” = 1 to “Never” = 6. The variable was then dummy coded so that “Never/Less than once a month” = 0, “Once a month” = 1, “Several times a week” = 2, and “Every day/More than once a day” = 3.

Religious service attendance was measured by asking, “How often do you attend services at a church/temple/synagogue/mosque?”. The answers were dummy coded so that “Never/Less than once a month” = 0, “Once a month/Several times a month” = 1, and “Once a week/Several times a week/Every day/More than once a day” = 2.

To see how respondents felt their religiosity impacted their perception of gender roles in the home, they were asked, “Using the categories shown below, please tell me how important religion is in different domains of your life regarding: How important gender roles are in the home.” The respondents could choose “Extremely important” = 3, “Somewhat important” = 2, “Not important” = 1, or “Not important at all” = 0.

A self-control index of 22 questions was used to gauge participants’ self-control. Questions were asked about their level of agreement with statements that pertained to the ability to control oneself. Examples of the questions asked included: (1) “I often act on the spur of the moment without stopping to think.” (2) “I do not devote much thought and effort to prepare for the future.” (3) “I often do whatever brings me pleasure here and now, even at the cost of some distant goal.” The respondents could answer “Strongly Disagree” = 0, “Disagree” = 1, “Agree” = 2, and “Strongly Agree” = 3.

Divine Control measured how much the respondents believed God controlled their lives. Four questions asked respondents how much they “Strongly Disagree” = 0, “Disagree” = 1, “Agree” = 2, and “Strongly Agree” = 3 with: (1) “I decide what to do without relying on God.” (reverse-coded). (2) “When good or bad things happen, I see it as part of God’s plan for me.” (3) “God has decided what my life shall be.” (4) “I depend on God for help and guidance.”

Feelings about Current Relationship. Questions asked respondents to gauge their “level of happiness toward their current relationship.” Responses consisted of “Very unhappy” = 0, “Unhappy” = 1, “Happy” = 2, and “Very happy” = 3.

Partner’s Church Attendance was measured and coded to examine the relationship between it and IPV attitudes. It was dummy coded to “Never/Less than one a month” = 0, “Once a month/several times a month” = 1, and “Once a week/More than once a week” = 2.

Alcohol use was also measured due to support from previous research (Grom et al., 2021). The variable was calculated by dummy coding: “Nearly every day/3-4 day per week/1-2 days per week” = 2, “1-2 days per month” = 1, and “less than once a month” = 0.

Control Variables

Sociodemographic variables were used to limit confounding variables, capturing a better grasp of where the data was coming from. These covariates included current relationship status, respondent age, family income, alcohol use, employment status, class/classification, gender, and race/ethnicity.

Results

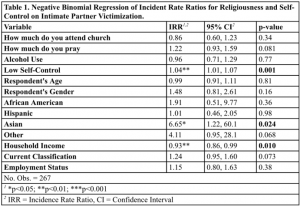

Students who had lower levels of self-control reported having minimally increased incidences (4%) of being victimized by their partner (IRR: 1.04; p<0.001) compared to those with more self-control. Compared to non-Hispanic Whites, Asian students reported a significantly higher likelihood of experiencing violence (IRR: 6.65; p<0.024). Stated differently, Asian students had a 565% increased likelihood of having been victimized by a partner. Lastly, those who reported having a higher household income were 7% (IRR: 0.93; p<0.01) less likely to have experienced partner violence.

Conclusion

This study sought to explore the prevalence of IPV among college students at a private university, with the aim of addressing the association between self-control, alcohol abuse, and partner violence among Hispanic/Latino students. Though there was not a direct link between Hispanic/Latino students and IPV, there was substantial evidence that low self-control is associated with IPV among college-aged students.

References

Tjaden, P., & Thoennes, N. (2000). Extent, nature, and consequences of intimate partner violence: Findings from the national violence against women survey. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, National Institute of Justice

National Domestic Violence Hotline. “Abuse in the Latinx Community.” The Hotline, www.thehotline.org/resources/abuse-in-the-latinx-community/.

Alvarez, Carmen, and Gina Fedock. “Addressing Intimate Partner Violence with Latina Women: A Call for Research.” Trauma, Violence & Abuse, vol. 19, no. 4, 2018, pp. 488–93. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/26638229. Accessed 25 Feb. 2025.

Rapp-Paglicci, Lisa A, Roberts, Albert R, Wodarski, John S. Handbook of Violence. New York, Wiley, 2002.

Maria Loreto Biehl, et al. Too Close to Home: Domestic Violence in the Americas. Washington, D.C., The Inter-American Development Bank, 1999.

Atske, Sara. “What U.S. Latinos Say about ‘Machismo.’” Pew Research Center, 17 Dec. 2024, www.pewresearch.org/race-and-ethnicity/2024/12/17/what-u-s-latinos-say-about-machismo/.

Flake, Dallan F., and Renata Forste. “Fighting Families: Family Characteristics Associated with Domestic Violence in Five Latin American Countries.” Journal of Family Violence, vol. 21, no. 1, Jan. 2006, pp. 19–29, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-005-9002-2.

Nason-Clark, Nancy, et al. Religion and Intimate Partner Violence: Understanding the Challenges and Proposing Solutions. Oxford University Press, 2018.

Davis, Maxine, and Melissa Jonson-Reid. “The Dual Use of Religious-Faith in Intimate Partner Abuse Perpetration: Perspectives of Latino Men in a Parish-Based Intervention Program.” Social Work & Christianity, vol. 47, no. 4, Dec. 2020, pp. 71–95. EBSCOhost, https://doi.org/10.34043/swc.v47i3.109.

Kantor, Glenda K., et al. “Sociocultural Status and Incidence of Marital Violence in Hispanic Families.” Violence and Victims, vol. 9, no. 3, Jan. 1994, pp. 207–222, https://doi.org/10.1891/0886-6708.9.3.207

Shrider, Emily. “Poverty in the United States: 2023.” United States Census Bureau, 10 Sept. 2024, www.census.gov/library/publications/2024/demo/p60-283.html.

Latinas and Intimate Partner Violence Evidence-Based Facts. esperanzaunited.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/3.11.73-Factsheet_GeneralIPV2021.pdf.

Caetano, Raul, et al. “Intimate Partner Violence and Drinking Patterns among White, Black, and Hispanic Couples in the U.S.” Journal of Substance Abuse, vol. 11, no. 2, July 2000, pp. 123–138, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0899-3289(00)00015-8. Accessed 8 Mar. 2020.

Martens, Tamera. “Relationship between Drug Addiction, Alcoholism, and Violence.” American Addiction Centers, 2 Dec. 2022, americanaddictioncenters.org/rehab-guide/addiction-and-violence.

Latin@ Children and Youth Exposed to Domestic Violence. esperanzaunited.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/3.11.89_Factsheet_YouthWitness2021.pdf.

Murrell, Amy R., et al. “Characteristics of Domestic Violence Offenders: Associations with Childhood Exposure to Violence.” Journal of Family Violence, vol. 22, no. 7, 17 July 2007, pp. 523–532, link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10896-007-9100-4, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-007-9100-4.

Zarah Zurita Quiroga, “Inter-Generational Transmission of Violence in Latino Families: The Role of Mothers in Navigating the Cycle of Abuse” University of Delaware student research https://digitalcommons.providence.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1095&context=sbg#:~:text=This%20theory%20hypothesizes%20that%20a,from%20one%20generation%20to%20another.

Shorey, Shefaly, and Sara Baladram. “‘Does It Really Get Better After Dad Leaves?’ Children’s Experiences With Domestic Violence: A Qualitative Systematic Review.” Trauma, Violence & Abuse, vol. 25, no. 1, Jan. 2024, pp. 542–59. EBSCOhost, https://doi.org/10.1177/15248380231156197.

Romo, H.D. (2008). The extended border: A case study of San Antonio as a transnational city. Transformations of La Familia on the U.S.-Mexico Border. 77-104.

“St. Mary’s University | Data USA.” Datausa.io, 2022, datausa.io/profile/university/st-Mary’s-university. Accessed 28 Feb. 2025.

Straus, Murray A, Sherry L Hamby, Sue Boney-McCoy and David B Sugarman. 1996. “The Revised Conflict Tactics Scales (Cts2) Development and Preliminary Psychometric Data.” Journal of Family Issues 17(3):283-316.

Garcia-Moreno, Claudia, Henrica AFM Jansen, Mary Ellsberg, Lori Heise and Charlotte H Watts. 2006. “Prevalence of Intimate Partner Violence: Findings from the Who Multi-Country Study on Women’s Health and Domestic Violence.” The Lancet 368(9543):1260-69.

“U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: San Antonio City, Texas.” Www.census.gov, www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/sanantoniocitytexas/PST045223.

Willems, Yayouk, et al. “The Relationship between Family Violence and Self-Control in Adolescence: A Multi-Level Meta-Analysis.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, vol. 15, no. 11, Nov. 2018, p. 2468, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15112468. Accessed 16 Oct. 2020.

Buddy, T. “How Domestic Violence Varies by Ethnicity.” Verywell Mind, 26 Apr. 2021, www.verywellmind.com/domestic-violence-varies-by-ethnicity-62648.

3 comments

TJ

The article clearly explains how norms like machismo and familism can lead to partner violence in Latino communities. The part about how religious beliefs can keep survivors from getting help was eye opening. Using survey data from a Hispanic serving university gave the study a relevant, real world feel. The breakdown of alcohol’s role and the focus on how children are affected made the piece well rounded and showed both the research side and the human side of the issue.

Micaella Sanchez

This research underscores the urgent need to address intimate partner violence within Latino communities by examining the complex interplay of culture, religion, and economic pressures, which can be a significant issue in a society. Highlighting the experiences of college students at a Hispanic-serving institution contributes a valuable and often overlooked perspective. It also emphasizes the importance of culturally tailored prevention strategies and deeper, ongoing research into intergenerational patterns of abuse. It was very informative on this topic.

Carlos Flores

Wow, what an outstanding article. You did a phenomenal job not only capturing the depth of the topic but also presenting it in a way that’s genuinely engaging and insightful. Your writing stands out with its clarity, organization, and thoughtful analysis — it’s clear you put a lot of effort and passion into this piece. Every point you made was well-supported and flowed naturally, making it a pleasure to read from start to finish. Truly impressive work — you should be proud.