One day in 1685, a shepherd in Arabia noticed that his goats were acting more lively than usual after eating an unknown fruit. When the shepherd told his friends in the monastery to prepare a drink for him, he too probably felt the same effects, feeling full of energy and bounding around the room. It would not be hard to believe that both the shepherd and the clergyman were astonished by this bitter miracle drink, and wanted to spread this new invention around their town and eventually, the world. That is not the only thing that happens that year.

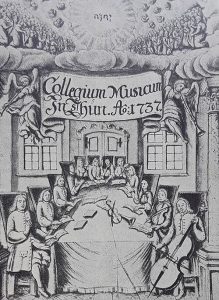

Johann Sebastian Bach was born in the small duchy of Saxe-Eisenach, and quickly became the Eisenach town musician with an amazing talent. But he also had a more rebellious side to him as well. Later in his life, he became more of a headache for the city of Leipzig, where he and his band of musicians were currently living. After such time with the introduction of coffee in the markets, the markets were probably flourishing with this miracle drink, and both good and bad influences, as well as rumors, started to spread throughout the world for being a drink that can cure intoxication. But because of this, coffee was then associated with drunkards, and many officials saw places that served coffee as “breeding places for immorality and light-heartedness.” And because of this, they would try to stop the distribution of coffee and eventually outright ban the beverage in 1697, which impacted Paris the most, as it had 380 establishments impacted by such a rule. Bach performed in many of these coffeehouses with his band, the Bach Collegium Musicum, and it would not be hard to believe that Bach felt infuriated about the restrictions that were taking place. Bach, always having his rebellious side to him, would soon think of a clever way to poke fun at those same government officials.1

The town of Leipzig, which was probably once filled with laughter and debate, was now less lively; it was as if the very soul of Leipzig was stolen away by a higher power because of this coffee ban. The once lively regulars of the coffeehouses were likely gossiping in quiet murmurs about how their harmless joy was robbed from them by higher powers that had no idea what was really happening in their own town. The musicians who once relied on these coffeehouses were probably now questioning whether their art would make such an impact as it once did and if their livelihoods were now at stake. The young musical scholars of Leipzig were surely depressed that their inspiration would be outlawed for seemingly no reason other than paranoia, and whether their space of daily inspiration would have to be sourced from somewhere else. Bach, sitting in the Zimmerman cafe, likely thought about how such a ruling on coffee even came into being and how this ruling would impact the coffeehouses that he had performed in regularly, and robbed him of one of his few outlets for expressing his musical freedom. Not just Bach but many citizens of Leipzig likely believed that this new ruling could make those coffeehouses go out of business or lose the charm they once had in order to adapt to these new rules. Bach, sitting in the Zimmerman cafe with his Collegium Musicum, was likely discussing why the city officials and the Saxe-Eisenach government did such a thing. Coffee had been around a long time, and there had been no health problems associated with it that they knew of.2

Suddenly, it would be easy to believe a beam of inspiration hit Bach; he and his Collegium Musicum couldn’t solve the problem associated with coffee, but they could probably at least find fun in a serious problem, as well as liven this city one more time. Bach began to write a cantata or short play about the coffee controversy in order to get back at the people who hurt Leipzig. This cantata would be known as the “coffee cantata,” and in this play, Bach intended to poke fun at all of the controversy around coffee at the time. These rebellious and bold emotions were not a rare thing to see from Bach: “for various reasons, [Bach] gave the Leipzig city council, the church officials, the city musicians and the choir students many a headache.”3 Many people in Leipzig surely already knew Bach for causing trouble around the city, making plays about politics as well as slandering other musicians through writing letters. The city of Leipzig probably still could not deny that Bach had an incredible talent, even with his playful nature, and if anyone were to go against the government in such a way and make a great impact, it would not be hard to believe that no other person would be more qualified and more suited for the job than Bach.

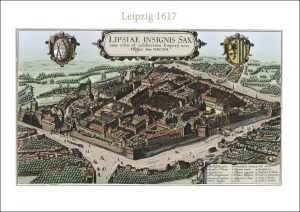

| Courtesy of stadtplan verlag leipzig

Bach was probably not the first person to be enraged about the restrictions placed on coffee, and many other musicians saw coffee in high regard. These musicians often were seen with coffee to help them write for long periods at a time, and some musicians saw it as an extreme necessity after a while. “Coffee, coffee is my life, Coffee is the potion of the gods. Without coffee I am ill. Even the sweet juice of the vine is superseded by coffee. For if I want to climb the hill of Pindus and want to devise a poem, I need only a cup of coffee, and, should opportunity lend itself, smoke a pipe of tobacco with it. –Then I sense immediately that the muscles favor my pen.” — Johann Gottfried Krause.4 Bach and Krause were probably seen in the Zimmerman cafe, discussing how much coffee had impacted the people of Leipzig and how many people likely thought the same way that he had about coffee. But in this likely scene, Krause brought Bach close after smoking from his pipe and told him the outrageous claims and actions that the religious and civic leaders had about coffee. Krause probably told Bach about how, back in 1697, the Leipzig city council started sending councilmen to coffee houses, arresting women, and in the worst cases, beating them for being associated with the establishments and what they did in there as well. Bach, probably infuriated and motivated by this new information, finally finished the cantata after five years and was almost ready to perform it. It would not be hard to believe that Bach talked with his Collegium Musicum with a smirk on his face, finally showing them his final creation, which led to an uproar of laughter. And with the first time in a while, hearing laughter surrounding Bach, he knew he had his cantata ready. It was time to bring joy back into this blue town.

The year was 1736 on a Friday night, and it would not be hard to believe that almost every seat in the Zimmerman cafe was full of people whispering about what Bach had prepared for them.5 The customers of the Zimmerman cafe probably whispered to each other about rumors of this play being a form of protest against the city leader’s outrageous laws on coffee, which had been impacting the businesses and the citizens’ lives for decades now. As the musicians were surely getting ready, Bach probably looked out at the audience and noticed the city officials sitting at the back of the cafe, standing out from the crowd by wearing very fine clothes and having serious looks on their faces. Likely, Bach grinned mischievously as he knew what was in store for them soon.6

As the Cafe quieted down, the curtains began to rise to a man named Schlendrian, probably pacing back and forth. He surely stopped to tell the audience that no matter what, he cannot seem to get his daughter, Lieschen, to stop drinking coffee, that it is unhealthy and unfitting for a woman to be drinking such a beverage.7

Mid-explanation from the father, Lieschen probably skipped into the room with an aloof smile on her face. She sang to her father to calm down, and that coffee has not done anything to her; in fact, she probably had never felt more aware and happy since she had started drinking coffee.8

Schlendrian crossed his arms judgmentally and sang that even after a hundred thousand times, Lieschen will not listen to him, that he surely only cared for his daughter, and based on what the city officials had said, it was likely that coffee was unhealthy and only for poor drunkards recovering from last night’s drink.9

Lieschen spoke up to her father and surely said, “Those city councilmen? They do not know a thing about us and how we live. Why do they have the right to say what we should and should not drink when they have never tried it themselves!” It would not be hard to believe that the audience murmured in agreement. Lieschen then sang, “Do not be so easily fooled, father! It is making you too strict. Without my three cups of coffee a day, oh what misery! I might as well shrivel up like a roast goat!”10

For the first time in what probably seemed like years, it would not be hard to believe that the audience began to laugh. The audience surely raised their drinks in the air and began to sing alongside Lieschen, applauding and embracing one another. Bach likely looked back at the audience and saw the life that Leipzig once had. Just for the briefest of moments, it could be believed that it seemed like the soul of Leipzig had been reignited that night, and its people could finally have an outlet to forget their worries as they had once before. Bach, very likely with a grin on his face, looked to the back of the Zimmerman cafe to see the city officials, once serious, now anxious and shifting in their seats. All that the proud city councilmen could do now was smile awkwardly and applaud meekly.11

Once the crowd began to calm, Schlendrian stomped his foot in anger and said. “Enough jokes! If you cannot listen to your father’s orders, I will take away the very food you eat! I will take away the nice clothes I worked so hard to provide for you! I shall take away all the pleasantries in your life if you continue to drink that accursed coffee!”12

Lieschen then crossed her arms and turned away from her father. Lieschen began to sing, “Fine! Take anything you see fit, I will get much more warmth from my coffee than I have ever had from you!” As Lieschen likely turned away from her father, Schlendrian put a finger to his chin and began to pace back and forth once more.13

It would not be hard to believe that the audience had been silenced for the moment as the air in the Zimmerman cafe had become tense from the anticipation. Then suddenly, for dramatic effect, it can be believed that both the musicians and Schlendrian stopped; it probably looked like Schlendrian had come up with an idea. Schlendrian hurriedly walked over to Lieschen and turned her around quickly.14

“If you are so adamant about drinking coffee, then I will forbid you from marrying until you learn to change!”

The aloof attitude in Lieschen suddenly ceased, her face became pale, and she started to shake. As Schlendrian likely began to walk away, Lieschen hurried after her father, pleading with him not to do such a cruel thing. Lieschen finally said she will stop drinking coffee as long as she can still marry.15

Schlendrian stopped for a moment. “Good, then maybe you will finally get a husband. I’ll help you by beginning the search for someone myself.”

Right before the curtains closed, Lieschen looked back at the audience, smiling. She winked and then skipped off stage once more.

As the curtains closed and the shuffling of props was heard backstage, the silence stayed in the audience, and whispers could probably be heard talking about what they thought they would see next. One final time, Bach probably looked to the back of the Zimmerman cafe and did not see the city councilmen anymore. Bach likely began to smile as it seemed the council had already guessed what would happen next. As the curtains began to rise once more, Bach surely knew he had won both the hearts of Leipzig as well as had made another defiant statement.

The curtains rose to something similar to an outdoor cafe setting, with a nicely dressed man sitting with Lieschen, and they were both probably laughing. Lieschen and the man both got up from their chairs and likely began to walk to the front of the stage. Lieschen and the man began to raise both hands in the air for the audience to see; in one hand, they had a ring, and in the other, they had a cup of coffee.16

After a moment, it would not be hard to believe that the silence was broken by the audience beginning to cheer once more, standing from their seats and applauding so loudly it would not be hard to believe it shook the building. Soon, the musicians probably began to play again, and all the characters took to the stage to sing that coffee would remain here in Leipzig, that the women would still drink their coffee just as their mothers and grandmothers had.17

As the customers of the Zimmerman cafe probably returned home, singing the songs from the play, Bach reflected on the evening. Bach had done something bigger than just perform; it would not be hard to believe that he had brought back the voice to Leipzig that could hopefully be the start of straightening the whole coffee problem out. Bach surely went home that night hoping his performance brought back the rebellious spirit in the citizens of Leipzig, and if not, then he was probably happy that he had brought joy to a problem devoid of it, even if it was for just a moment.

- Hans-Joachim Schulze and Alfred Mann, “Ey! How Sweet the Coffee Tastes: Johann Sebastian Bach Coffee Cantata in Its Time / Ey! Wie Schmeckt Der Coffee Süsse: Johann Sebastian Bachs Kaffee-Kantate in Ihrer Zeit,” Bach, vol. 32, no. 2 (2001): 8. ↵

- Hans-Joachim Schulze and Alfred Mann, “Ey! How Sweet the Coffee Tastes: Johann Sebastian Bach Coffee Cantata in Its Time / Ey! Wie Schmeckt Der Coffee Süsse: Johann Sebastian Bachs Kaffee-Kantate in Ihrer Zeit,” Bach, vol. 32, no. 2 (2001): 3. ↵

- Hans-Joachim Schulze and Alfred Mann, “Ey! How Sweet the Coffee Tastes: Johann Sebastian Bach Coffee Cantata in Its Time / Ey! Wie Schmeckt Der Coffee Süsse: Johann Sebastian Bachs Kaffee-Kantate in Ihrer Zeit,” Bach, vol. 32, no. 2 (2001): 3. ↵

- Hans-Joachim Schulze and Alfred Mann, “Ey! How Sweet the Coffee Tastes: Johann Sebastian Bach Coffee Cantata in Its Time / Ey! Wie Schmeckt Der Coffee Süsse: Johann Sebastian Bachs Kaffee-Kantate in Ihrer Zeit,” Bach, vol. 32, no. 2 (2001): 14. ↵

- Hans-Joachim Schulze and Alfred Mann, “Ey! How Sweet the Coffee Tastes: Johann Sebastian Bach Coffee Cantata in Its Time / Ey! Wie Schmeckt Der Coffee Süsse: Johann Sebastian Bachs Kaffee-Kantate in Ihrer Zeit,” Bach, vol. 32, no. 2 (2001): 12. ↵

- “Cantata BWV 211 – English Translation,” Bach-Cantatas.com, last modified January 9, 2023, https://www.bach-cantatas.com/Texts/BWV211-Eng3.htm. ↵

- “Cantata BWV 211 – English Translation,” Bach-Cantatas.com, last modified January 9, 2023, https://www.bach-cantatas.com/Texts/BWV211-Eng3.htm. ↵

- “Cantata BWV 211 – English Translation,” Bach-Cantatas.com, last modified January 9, 2023, https://www.bach-cantatas.com/Texts/BWV211-Eng3.htm. ↵

- “Cantata BWV 211 – English Translation,” Bach-Cantatas.com, last modified January 9, 2023, https://www.bach-cantatas.com/Texts/BWV211-Eng3.htm. ↵

- “Cantata BWV 211 – English Translation,” Bach-Cantatas.com, last modified January 9, 2023, https://www.bach-cantatas.com/Texts/BWV211-Eng3.htm. ↵

- “Cantata BWV 211 – English Translation,” Bach-Cantatas.com, last modified January 9, 2023, https://www.bach-cantatas.com/Texts/BWV211-Eng3.htm. ↵

- “Cantata BWV 211 – English Translation,” Bach-Cantatas.com, last modified January 9, 2023, https://www.bach-cantatas.com/Texts/BWV211-Eng3.htm. ↵

- “Cantata BWV 211 – English Translation,” Bach-Cantatas.com, last modified January 9, 2023, https://www.bach-cantatas.com/Texts/BWV211-Eng3.htm. ↵

- “Cantata BWV 211 – English Translation,” Bach-Cantatas.com, last modified January 9, 2023, https://www.bach-cantatas.com/Texts/BWV211-Eng3.htm. ↵

- “Cantata BWV 211 – English Translation,” Bach-Cantatas.com, last modified January 9, 2023, https://www.bach-cantatas.com/Texts/BWV211-Eng3.htm. ↵

- “Cantata BWV 211 – English Translation,” Bach-Cantatas.com, last modified January 9, 2023, https://www.bach-cantatas.com/Texts/BWV211-Eng3.htm. ↵

- “Cantata BWV 211 – English Translation,” Bach-Cantatas.com, last modified January 9, 2023, https://www.bach-cantatas.com/Texts/BWV211-Eng3.htm. ↵

1 comment

Maya Inomata Hernandez

I thought the way you mixed real historical details with creative descriptions was super interesting. The narrative parts, like imagining Bach smirking at the officials or Lieschen skipping onto the stage, made your article seem like a story!