In recent years, forensic science has developed techniques that provide the ability for law enforcement to perform investigations, such as familial DNA searching. Familial DNA searching analyzes databases to find relatives of perpetrators based on a partial genetic profile. While this method helps identify a suspect when full matches are unachievable, it also raises ethical concerns about privacy and consent. As this technique is continually practiced, ongoing debates are becoming prevalent with scientists, the public, and legal experts. This is especially true when using this DNA technique to narrow down the Golden State Killer, but falsely identify someone like Michael Usry Jr. for a crime they weren’t connected to. The application of familial DNA searching is a valuable tool for tracing a perpetrator back to a crime scene but challenges morality regarding privacy issues and overzealous actions by law enforcement, impacting several family members and falsely accused persons.

The development of DNA fingerprinting in 1984 formed a foundation in modern forensic science, introducing both the potential justice and ethical dilemmas that familial DNA searching amplifies. In 1984, DNA fingerprinting was discovered by Alec Jeffreys, which allowed for repetitive DNA sequences to be tested for in criminal investigations.1 Now, fingerprinting is prominent in studying for the identification of an individual. However, some issues arise with this discovery. Now, over the recent years, there have been ethical issues concerning familial privacy and abuse of power when utilizing forensic genomics. Law enforcement uses DNA for familial searching to identify suspects can blur into genetic surveillance and invasion of privacy. Investigating relatives for genetic information can exploit CODIS, using data to fill gaps that may not exist.2

However, using such techniques in forensic science has led to exonerations of criminals who were falsely accused of a crime in earlier years, and convicting criminals as well. While it is not direct, relatives of a suspect can help law enforcement to convict or overturn a case. When thinking about genetic surveillance, some states implement laws to ensure that CODIS is being utilized at proper discretion, while upholding their standards. Not only the proper use of CODIS, but also other databases, such as Ancestry. In addition, there are proper communication channels being upheld to ensure privacy and transparency among all involved in familial searching.2

Understanding familial searching begins with understanding forensic science and its necessity for this type of searching. Forensic science is an application of science to the law and justice system and there are different scientific evidence presented for an investigation. Science becomes involved in several ways through drug analysis, trace evidence, and DNA analysis. DNA analysis in forensic science was developed into DNA fingerprinting in 1984 by Sir Alec Jeffreys. Sir Alec Jeffreys developed a technique that would eventually become one of the highest discriminatory techniques that would convict and exonerate individuals. Eventually, his technique would also evolve into familial DNA searching, where a suspect’s DNA is matched with family relatives to secure a match based on their original match from the crime scene.

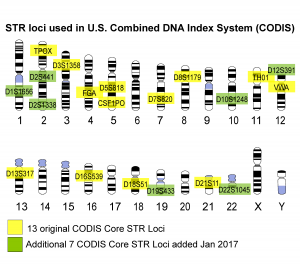

DNA analysis involves collecting crime scene samples and reference samples to exclude non-suspects. In forensic science, DNA is tested through different techniques, such as Short Tandem Repeats (STR). Short tandem repeats are small variable, non-coding repeats, that are now used for identifying variation from one individual to another.4 STRs are preferred over other methods because they contain shorter base pair sequences than Variable Number Tandem Repeats and Restricted Fragment Length Polymorphisms. STR undergoes a specific workflow to analyze different base pair changes along repeats of the analyst’s choosing.4 STRs are the main foundation of DNA profiles on CODIS by using alleles from 20 core loci. These 20 core loci make investigations easier since there are many sequences that can be observed and help narrow down non-coding sequences. However, STR analysis is not without limitations. Because STR testing relies on statistical probabilities of allelic frequencies within populations, even small overlaps can lead to false positives or coincidental matches. Partial samples can increase the chance of misinterpretation, especially when analysts rely on partial loci or mixed samples.6 These scientific uncertainties may have major ethical consequences, such as wrongly implicating individuals based on coincidental genetic similarities. Furthermore, highlighting the necessity for cautious and transparent interpretation in familial DNA searching.

While there are different repeats and sequences from the genome that can be tested, there are several reasons why familial searching is useful. When direct DNA matches are unavailable, investigators may turn to familial DNA to identify genetic similarities between the crime scene sample and potential relatives. Also, when there happens to be a cold case, several methods may fail along the investigation process, which leads to a last option of using familial DNA. The purpose of this technique is to continue having different alternatives to approaching a suspect.7

In 2002, familial searching was first enhanced in forensic investigations in the United Kingdom by their forensic science services. Since their implementation, one of the most prominent cases using familial DNA searching was the Golden State Killer, Joseph James DeAngelo, in 2018.8 Joseph James DeAngelo was a former police officer who murdered and raped women throughout California. Over 40 years, he managed to get away with his crimes because of his former work as a police officer. However, familial DNA searching showed that his DNA had no place to hide in the eyes of law enforcement. Investigators uploaded his DNA profile into a database, then compared it to others to identify genetic relatives. Then, the similar profiles are then composed into a family tree for further identification and went as far as third cousins of the Golden State Killer. As stated from earlier, many of the genetic profiles are composed of results from Ancestry and 23andMe, which can provide information from those who haven’t been convicted in a court of law.9 However, it poses as an ethical issue regarding privacy and bias when identifying a suspect.

Familial DNA search raises serious questions about the privacy of relatives who become unwitting subjects of investigations. While performing familial searching there are issues that come at hand because of violation of genetic privacy.7 While the Golden State Killer has been caught, there are other cases, where one is falsely reprimanded for one’s crimes. One of these cases where false accusations occurred was with Michael Usry Jr. He was falsely accused of murdering an Idaho teenager, Angie Dodge, after performed familial searching went wrong. In 2014, the investigators used a semen sample from the crime scene, which was entered into a public database purchased by Ancestry.11 There was a partial match between Michael’s father and the semen sample from the crime scene. Because of this damning evidence, they assumed that the questionable DNA sample actually belonged to Michael Usry Jr. since it was a partial match. With the subjective opinions, the power of abuse led to Usry Jr. not being allowed to ask any questions without being properly questioned by police.

Implications of familial DNA searching have led to risky approaches in law enforcement. Because partial matches do not guarantee biological relations, their accuracy often remains uncertain. As mentioned with Usry, this accusation was impactful as a DNA search gone wrong. As a result, there was a violation of privacy with Michael Usry Jr. since his and his father’s DNA was used without their consent.12 Databases meant for personal genealogy have increasingly become investigative tools for law enforcement’s private hold for DNA. While there are around 50% of people who consent to law usage, there are still the other half who don’t consent to their DNA being used. Why is this the case if their DNA is possibly used anyway? With investigations, there are scenarios where consent isn’t necessary, especially when using samples in criminal cases. However, this doesn’t excuse the issue behind privacy due to certain amendments. The submission of DNA is protected under the Fourth Amendment, which allows utilization of DNA only for what one submitted for.7 Therefore, the usage of DNA from Ancestry and 23andMe can be used for ancestry but hits a grey area while in law enforcement.

Continuing on Michael Usry Jr., his privacy was violated where he had no clue his DNA was involved with law enforcement in the first place. During one of his interviews, he stated that he felt confused when police cars arrived at his home. The same went for his father when he first got news of it. The investigation began when Michael Usry Sr. voluntarily donated a DNA sample through his Mormon church to explore his family history, unaware it would be used in a criminal investigation. Unfortunately, for him and his son, it would be an unexpected turn of events. Both the father and son felt their privacy was violated because they have no expectation that the father’s sample would be utilized for law enforcement purposes. As a result, the Usry family lost trust in legal proceedings of evidence and simple DNA websites, such as Ancestry and 23andMe.12 Another issue at hand is discoveries of unknown origin to a criminal case. When performing familial searching, family members may learn of their relative’s involvement which also includes breaching confidentiality.12 Some family members may not be aware that one of their own was involved or arrested for a crime. Not only revealing such information but also revealing the genetics of all family members involved in investigations. Much of this information could lead to societal impact on families, such as estrangement or domestic violence.

From the Catholic moral perspective, these ethical concerns raised by genetic surveillance emphasize the balance between human autonomy and responsibility of community welfare. Catholic social teaching emphasizes that every human possesses dignity, created in the image of God, must never treat anyone merely as a means to an end. When law enforcement uses familial DNA databases without consent, there is a morality risk of violating human autonomy and privacy, both of which stem from the right to bodily integrity. However, catholic ethics also uphold importance of justice and the common good, which calls for society to tell the truth, protect innocence, and prevent further harm. Thus, familial DNA searching can align with Catholic values when it is being used as a form of stewardship, respecting both the scientific process and human dignity. This means using familial DNA for legitimate justice, not just a tool to overreach. Ultimately, Catholic teaching reminds us that technology must serve the human person, not dominate them, and that justice is truly achieved when it respects the dignity of every person involved.

Regardless of these aspects, familial DNA searching has performed well as a tool for solving cold cases, therefore providing closure to families. As said prior, familial searching has been helpful in solving cold cases when there are no leads for a DNA match. Systems such as CODIS may not have anything useful compared to familial searching in several cold cases. In addition to this, also provides closure to several families. Part of using this technique helps to provide justice and closure to all victims and families involved.

The ethical impact of familial DNA searching depends largely on how law enforcement uses this resource. Particularly, when performing the search through misuse of power through determining a family tree without proving so. According to the Human Genome Project, 99.5% of our DNA is identical to one another, so there are still similarities among individuals who are non-relatives to each other.16 Creating family trees based on “matches” is still detrimental because of human error. When falsely accused, this could create an issue, which can lead to consequences and taking time away from innocent people. Furthermore, impacting our trust in the criminal justice system and legal processing of forensic evidence.

As forensic technology evolves, new methods may refine or eventually replace familial DNA searching. Forensic science has evolved over a long time since 1984 with the one of the first DNA techniques, then implementing the STR workflow to replace RFLP techniques. With continuous research and high demand for forensic science workers, there are greater chances to continue reform for law systems and DNA technology. Until then, the criminal justice system must continue to improve policies on consent and proper resources when searching for a DNA match.7 Since the criminal system tends to use subjective observations, most of law enforcement are continuing to improve and implement different ways to hold techniques to a higher standard for accreditation purposes.

The application of familial DNA searching continues to shape the future of forensic science by bridging cold, unsolved cases to modern technology. However, careful consideration must be applied regarding the moral questions of genetic privacy, consent, and law authority over DNA data. While the benefits of this technique are substantial, its ethical use depends on human judgement and respect for genetic autonomy. Due to this, investigators must be cautious when performing such searches to prevent this technique from becoming a negative impact on the criminal justice system, where one would no longer have trust.

- Isabel Wolfe, “Foregone Forensics: A Brief History of Crime Solving,” Yale Scientific, March 23, 2016, https://www.yalescientific.org/2016/03/foregone-forensics-a-brief-history-of-crime-solving. ↵

- Joyce Kim et al., “Policy Implications for Familial Searching – Investigative Genetics,” BioMed Central, November 1, 2011, https://investigativegenetics.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/2041-2223-2-22. ↵

- Joyce Kim et al., “Policy Implications for Familial Searching – Investigative Genetics,” BioMed Central, November 1, 2011, https://investigativegenetics.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/2041-2223-2-22. ↵

- Udogadi Nwawuba Stanley et al., “Forensic DNA Profiling: Autosomal Short Tandem Repeat as a Prominent Marker in Crime Investigation,” The Malaysian journal of medical sciences : MJMS, August 19, 2020, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7444828/. ↵

- Udogadi Nwawuba Stanley et al., “Forensic DNA Profiling: Autosomal Short Tandem Repeat as a Prominent Marker in Crime Investigation,” The Malaysian journal of medical sciences : MJMS, August 19, 2020, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7444828/. ↵

- Ana Bennett, “A Troubleshooting Guide for Common Issues in STR Analysis,” Forensic On the Scene and In the Lab, June 7, 2024, https://www.forensicmag.com/Forensic-Tips/613460-A-Troubleshooting-Guide-for-Common-Issues-in-STR-Analysis/. ↵

- “An Introduction to Familial DNA Searching,” Department of Justice, accessed October 9, 2025, https://bja.ojp.gov/sites/g/files/xyckuh186/files/media/document/an_introduction_to_familial_dna_searching1.pdf. ↵

- Sarah Chu and Susan Freidman, “Maryland Just Enacted a Historic Law Preventing the Misuse of Genetic Information,” Innocence Project, June 1, 2021, https://innocenceproject.org/news/maryland-passes-forensic-genetic-genealogy-law-dna/. ↵

- Holland, Hannah. “DNA Sampling Expands to Unethical Usage.” UHCL The Signal, April 22, 2019. https://www.uhclthesignal.com/wordpress/2019/04/22/dna-sampling-expands-to-unethical-usage. ↵

- “An Introduction to Familial DNA Searching,” Department of Justice, accessed October 9, 2025, https://bja.ojp.gov/sites/g/files/xyckuh186/files/media/document/an_introduction_to_familial_dna_searching1.pdf. ↵

- Huff, Richard. “A Brutal Murder – Police Have DNA Evidence, but Can’t Match a Killer – so How Did a Young Filmmaker End up a Murder Suspect?” Paramount Press Express, August 5, 2023. https://www.paramountpressexpress.com/cbs-entertainment/shows/48-hours/releases/?view=47531-a-brutal-murder-police-have-dna-evidence-but-cant-match-a-killer-so-how-did-a-young-filmmaker-end-up-a-murder-suspect-2. ↵

- Brangham, William, Nsikan Akpan, and Rhana Natour. “A Father Took an At-Home DNA Test. His Son Was Then Falsely Accused of Murder.” Public Broadcasting Service, November 7, 2019. https://www.pbs.org/newshour/show/a-father-took-an-at-home-dna-test-his-son-was-falsely-accused-of-murder. ↵

- “An Introduction to Familial DNA Searching,” Department of Justice, accessed October 9, 2025, https://bja.ojp.gov/sites/g/files/xyckuh186/files/media/document/an_introduction_to_familial_dna_searching1.pdf. ↵

- Brangham, William, Nsikan Akpan, and Rhana Natour. “A Father Took an At-Home DNA Test. His Son Was Then Falsely Accused of Murder.” Public Broadcasting Service, November 7, 2019. https://www.pbs.org/newshour/show/a-father-took-an-at-home-dna-test-his-son-was-falsely-accused-of-murder. ↵

- Brangham, William, Nsikan Akpan, and Rhana Natour. “A Father Took an At-Home DNA Test. His Son Was Then Falsely Accused of Murder.” Public Broadcasting Service, November 7, 2019. https://www.pbs.org/newshour/show/a-father-took-an-at-home-dna-test-his-son-was-falsely-accused-of-murder. ↵

- Rossiter, B J, and C T Caskey. “Impact of the Human Genome Project on Medical Practice.” Annals of surgical oncology, 1995. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7834449/. ↵

- “An Introduction to Familial DNA Searching,” Department of Justice, accessed October 9, 2025, https://bja.ojp.gov/sites/g/files/xyckuh186/files/media/document/an_introduction_to_familial_dna_searching1.pdf. ↵

1 comment

Dr. McLeod

Great job on this article, Abigail! Very well researched and thorough discussion of the ethical issues.