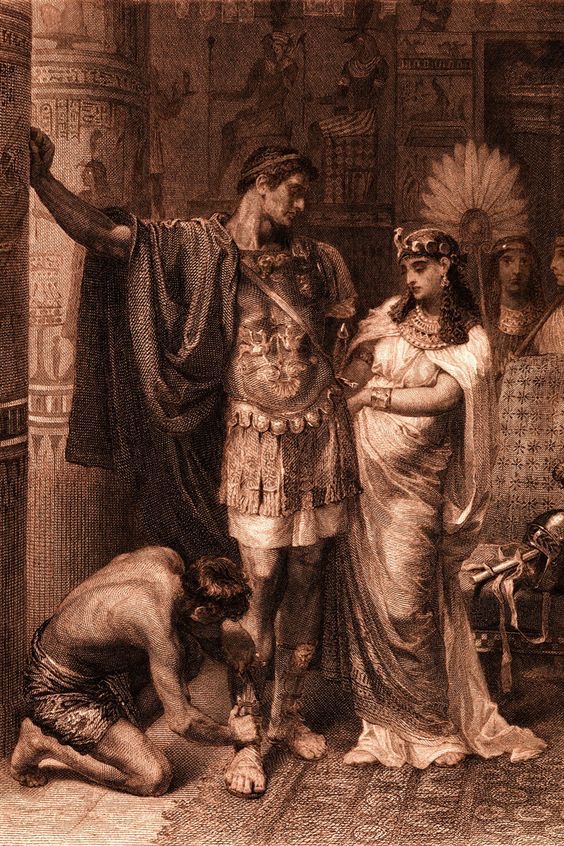

The Cydnus River of ancient Egypt experienced a burning sun as Cleopatra’s golden barge approached the city of Tarsus. The humid air created a blurring effect, while the strong smell of intensity drew people to gather along the riverbanks. The audience focused on Cleopatra as she sailed by wearing extravagant jewels and purple sails that made her the main attraction. Every action she performed and every look she gave was part of a strategic plan. Her remarkable beauty and self-assurance hid her actual motives. The display of confidence and luxury served as a strategic political maneuver. The throne of Egypt, along with its independence from foreign rule, depended on Cleopatra’s strategic actions. The success of Cleopatra’s kingdom and her historical legacy all relied on the outcome of her ability to meet Mark Antony, who waited at the shore.1

After Cleopatra and Antony’s first meeting was successful, Antony was invited to Alexandria, where the finest luxury and charm became Cleopatra’s most powerful weapons in Egypt.2 The two of them spent all the winter together enjoying banquets, music, and late-night debates. Cleopatra understood that to keep Egypt safe, she must keep Antony close. Behind the joyful laughter and wine, every conversation had a purpose behind it. Cleopatra offered Antony anything from money, ships, and even political support, resources he desperately needed. And in return, Antony would grant her control over parts of her lost empire.3 Cleopatra wasn’t after romance, but rather a strategy. She knew what she had to do to secure her throne, one decision at a time, blending love and ambition in a way that few rulers ever could.4

Cleopatra didn’t see the devastating news coming about Antony’s marriage to Octavia, the sister of his rival Octavian. The match was meant to ease tensions in Rome, but to Cleopatra, it felt like betrayal, and it hit hard like a stab. The powerful women who once commanded Antony’s full attention now suddenly stood at the edge of power once more. Still, Cleopatra refused to fade and fall apart. She sensed Antony’s ambitions reached past Rome; she also believed that one day Antony would return to her, and to Egypt too.5 Rather than mourning, she began to prepare. Cleopatra continued to rule Egypt and strengthen its power, ready for the moment when Antony’s loyalty might slip away, but her power wouldn’t fade then. The powerful queen of Egypt’s sharp thinking and pride shielded her, and her patience would soon be rewarded.6

In an attempt to restore his honor and prove his strength, Antony’s campaign against Parthia turned into a disaster. His loyal soldiers endured harsh deserts, suffered ambushes, and great hunger as the campaign fell apart.7 News of Antony’s failure reached Rome, completely damaging his reputation and giving power to Octavian. While in Egypt, Cleopatra saw an opportunity to act. As Antony returned defeated and drained, she greeted him with ships, supplies, and comfort. And instead of leaving him during his downfall, she stuck by him and became his rescuer. With Cleopatra by his side, Antony depended on Cleopatra’s wealth and support to help restore his army and his pride.8 As time went on, their partnership grew stronger, but the danger grew bigger. With every step they took together, they made themselves a bigger target for Rome’s anger.9

After the major failure in Parthia, Cleopatra and Antony built something to last more than just an alliance or romance; they began to build a dynasty. In Alexandria, the two presented themselves as more than just lovers but as rulers with a purpose. Antony presented himself as a god, and Cleopatra as both a goddess and a queen.10 As their bond grew closer, so did their power. It was no longer just political; it was a statement; they wanted to let the world know that Egypt and Rome could be united under their rule. Soon after, Cleopatra gave birth to twins, Alexander Helios, and Cleopatra Selene, and later to another son, Ptolemy Philadelphus.11 Their children symbolized power, legacy, and a new dynasty.

Cleopatra had a brilliant decision to tie her children’s identities to Egypt’s royal image as a political move. She organized public ceremonies, created coins with their portraits, and began shaping them into successors of Egypt and Rome.12 Antony went along with her plan because he found her leadership style and her determination to be impressive. But in Rome, Octavian exploited this to make the Roman people doubt Antony’s loyalty to Rome. Later, rumors spread about Antony leaving his Roman wife, Octavia, and that Cleopatra had bribed him with money and romance.13 The family that Cleopatra had built as her strength became a tool for her enemies to use against her.14

The Donations of Alexandria happened thanks to Cleopatra’s growing strength and ambition. For several years, she worked nonstop to restore Egypt, her plans and ideas confirmed her as an independent and divine ruler while setting up thrones for her children down the line.15 The plan was risky; one misstep could shield her dynasty, or spark Rome’s wrath. Cleopatra and Antony teamed up to get the ceremony ready, turning it into a meaningful celebration and a statement. Inside Alexandria’s Gymnasium, surrounded by gold decor, soft silk, and the scent of incense, Cleopatra stepped out among the crowd dressed as Isis. Standing at her side, Antony wore full Roman military attire as a symbol of unity between Eastern tradition and Western power.16 Their children sat on miniature thrones, wearing crowns to mark territories Antony had granted them. Cyprus, Syria, Armenia, and more.17

It wasn’t just a show; it was a declaration of who held real control. Cleopatra had finally reached her goal after years of effort, ever since that first meeting along the Cydnus River. She now had status, power, and authority, not only for herself but for her children as well. Yet across the sea in Rome, Octavian viewed this ceremony as a betrayal. In his eyes, Antony had crowned himself as a king abroad, under Cleopatra’s grip. This ceremony was intended to protect Egypt’s destiny; instead, it gave Octavian the reason he needed to start the war and tear everything down.18

The city of Alexandria sparked under the noon sun while thousands gathered to see a turning point no one saw coming during Cleopatra’s rule. Inside the grand gymnasium, marble pillars wore wraps of purple cloth, gold glimmering in the air with burning incense. Perched on an elevated throne beside Mark Antony, each framed by emblems tied to gods they claimed as protectors, Isis and Dionysus. Below them sat their children on smaller thrones, their little crowns catching flashes of sunlight.

Cleopatra’s voice was calm and steady, facing Egyptians and people from the eastern provinces. Antony announced the royal titles and lands he gave her, along with her children. Cleopatra earned the title “Queen of Kings,” while her son Caesarian received the title “King of Kings” and was seen as Caesar’s true successor.19 Just like that, she had achieved everything she’d been pushing for all along, her authority acknowledged, her dynasty, and her claim to rule confirmed.20

Still, right at the peak of success, there was unease. Beyond Egypt, news of the ceremony spread quickly through Rome, carried by murmurs among Octavian’s allies. For them, this showed that Antony had fallen under Cleopatra’s spell, betraying old Roman ways for a queen from another land. Her win, built on long efforts, strategy, charm, and courage, also lit the fuse for her downfall. In that single, stunning instant of glory, Egypt’s fate was sealed.21

Cleopatra’s achievements at the Donations of Alexandria echoed well past Egypt’s shores. Back in Rome, the news hit hard. To Octavian, Julius Caesar’s sharp-witted heir, the image of Antony bowing next to a non-Roman queen while crowning her “Queen of Kings” wasn’t just a shock; it was scandalous.22 He seized the moment, turning the public against the two and shaping anger into leverage. Cleopatra, once praised for her cleverness and charm, now stood for what Romans feared: dangerous, decadent, a threat.23

Octavian distributed what he claimed was Antony’s final “will.” Rumors spread that Antony planned to move Rome’s capital to Alexandria while giving Rome’s eastern territories to Cleopatra and her children. Whether this was true or not, this created widespread panic and anger among the population.24 The rumors transformed Cleopatra into an enemy who threatened Rome itself. Through her most impressive achievement, she got everything she wanted, her desired goals including official recognition, royal status, and a dynasty, but it also gave Octavian what he needed: a reason to declare war.25

Cleopatra and Antony, now surrounded, began to prepare for the attack. It all had started with a strategy and charm, but now it was time to desperately fight to survive.26

The victory Cleopatra and Antony achieved in Alexandria did not last long. The alliance between the two powerful bonds was now shadowed by the growing anger of Rome. In 31 BCE, the pair that had promised strength met their downfall at Actium, a small coastal city in Greece.27 Octavian’s military forces under Agrippa’s leadership closed in by land and sea. The Roman legions, with their disciplined formation, defeated Cleopatra’s naval force that had displayed her wealth and her pride.28

The battle was chaotic, and confusion spread across the water. The changing wind trapped Antony’s ships while his command rhythm started to break down. Cleopatra chose to leave her position at the back with her treasure ships. Cleopatra sailed through a narrow passage that led them toward Egyptian waters after the battle turned against them. Antony abandoned his command to chase after Cleopatra when he saw her escape from the battlefield. That decision he made at that moment marked the collapse of their power, whether it was driven by fear, strategy, or love.29

In Egypt, they attempted to strengthen their alliance, but they had lost all sense of control. Antony’s soldiers lost their trust in him after he abandoned them, while Octavian used propaganda to turn everyone against them.30 Their story, which began as a tale of passion, now focused on desperate survival. The queen who had ruled over kings now helplessly watched the collapse of the empire she had built.31

The defeat at Actium forced Cleopatra and Antony to seek refuge because they had no other option. Octavian’s military forces entered Egypt, surrounding Alexandria by 30 BCE, the city that had once been Cleopatra’s power base. The palace walls became her final defense as she refused to surrender to Octavian’s forces.32 She trapped herself inside with her treasure, plotting one last final plan. The defeat at Actium left Antony shattered by the loss and believing Cleopatra had betrayed him, so he lost all hope. When false news of her death reached him, he attempted suicide.

Injured and dying, Antony was transported to Cleopatra’s mausoleum, which served as her private sanctuary with her most loyal servants. One of the most haunting scenes of ancient history, Cleopatra had Antony pulled up to her through a window using ropes. The death of Antony was the end of her alliance, as she hung on to him in her arms as he passed away. For Cleopatra, the battle now focused on dignity rather than victory.33

Octavian arrived in the city. He promised her mercy, but she knew what he meant by that: a Roman parade, chains of humiliation, and her defeated queen status throughout Rome. Refusing to surrender and letting her legacy end in disgrace, Cleopatra chose her own fate. Wearing her royal robes and surrounded by symbols from her reign, she took her life. The exact method of her death remains unknown; some say she used a poisonous asp, while others say it was a fast-acting poison hidden inside her hairpin.34 Cleopatra made sure her death was her final act of control.35

Whether a gesture of respect or not, Octavian ordered Cleopatra to be buried beside Antony after he discovered her lifeless body.36 With her death, Egypt fell to Rome, bringing an end to three thousand years of pharaonic governance. The world remembers Cleopatra as more than just a queen; she became a legend, known for her intelligence and the fearless approach to her end.37

In Rome, Octavian jumped on the opportunity to build his image as the savior after Cleopatra’s death, soon after becoming the first emperor of Rome. And over centuries, Cleopatra refused to remain the villain in Rome’s story. Artists, poets, and historians continue to reimagine her as a seductress to some, and as a powerful woman to others. What made her stand out wasn’t just her beauty or her relationships, but her ability to rule in a world ruled by men.

- Joyce A. Tyldesley, Cleopatra: Last Queen of Egypt (New York: Basic Books, 2008), 149. ↵

- Adrian Goldsworthy, Antony and Cleopatra (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010), 93–94. ↵

- Duane W. Roller, Cleopatra: A Biography (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010), 82–84. ↵

- Duane W. Roller, Cleopatra: A Biography (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010), 83-84. ↵

- Adrian Goldsworthy, Antony and Cleopatra (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010), 164. ↵

- Arthur E. P. Brome Weigall, The Life and Times of Cleopatra: Queen of Egypt (London: Kegan Paul, 2013), 176–177. ↵

- Adrian Goldsworthy, Antony and Cleopatra (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010), 225–226. ↵

- Duane W. Roller, Cleopatra: A Biography (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010), 111. ↵

- Joyce A. Tyldesley, Cleopatra: Last Queen of Egypt (New York: Basic Books, 2008), 187. ↵

- Duane W. Roller, Cleopatra: A Biography (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010), 116–117. ↵

- Duane W. Roller, Cleopatra: A Biography (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010), 84–85. ↵

- Arthur E. P. Brome Weigall, The Life and Times of Cleopatra: Queen of Egypt (London: Kegan Paul, 2013), 189. ↵

- Adrian Goldsworthy, Antony and Cleopatra (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010), 274. ↵

- Joyce A. Tyldesley, Cleopatra: Last Queen of Egypt (New York: Basic Books, 2008), 198–199. ↵

- Duane W. Roller, Cleopatra: A Biography (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010), 126–128. ↵

- Arthur E. P. Brome Weigall, The Life and Times of Cleopatra: Queen of Egypt (London: Kegan Paul, 2013), 191. ↵

- Adrian Goldsworthy, Antony and Cleopatra (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010), 283. ↵

- Joyce A. Tyldesley, Cleopatra: Last Queen of Egypt (New York: Basic Books, 2008), 204. ↵

- Duane W. Roller, Cleopatra: A Biography (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010), 126–128. ↵

- Arthur E. P. Brome Weigall, The Life and Times of Cleopatra: Queen of Egypt (London: Kegan Paul, 2013), 190–191. ↵

- Joyce A. Tyldesley, Cleopatra: Last Queen of Egypt (New York: Basic Books, 2008), 204. ↵

- Adrian Goldsworthy, Antony and Cleopatra (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010), 283–284. ↵

- Duane W. Roller, Cleopatra: A Biography (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010), 134. ↵

- Joyce A. Tyldesley, Cleopatra: Last Queen of Egypt (New York: Basic Books, 2008), 208. ↵

- Adrian Goldsworthy, Antony and Cleopatra (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010), 286. ↵

- Arthur E. P. Brome Weigall, The Life and Times of Cleopatra: Queen of Egypt (London: Kegan Paul, 2013), 193. ↵

- Adrian Goldsworthy, Antony and Cleopatra (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010), 300–301. ↵

- Duane W. Roller, Cleopatra: A Biography (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010), 142–143. ↵

- Joyce A. Tyldesley, Cleopatra: Last Queen of Egypt (New York: Basic Books, 2008), 214–215. ↵

- Arthur E. P. Brome Weigall, The Life and Times of Cleopatra: Queen of Egypt (London: Kegan Paul, 2013), 198–199. ↵

- Duane W. Roller, Cleopatra: A Biography (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010), 145. ↵

- Adrian Goldsworthy, Antony and Cleopatra (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010), 309. ↵

- Arthur E. P. Brome Weigall, The Life and Times of Cleopatra: Queen of Egypt (London: Kegan Paul, 2013), 201–202. ↵

- Duane W. Roller, Cleopatra: A Biography (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010), 151–152. ↵

- Bust of Cleopatra VII,” Encyclopaedia Romana, University of Chicago, accessed October 2025. ↵

- Adrian Goldsworthy, Antony and Cleopatra (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010), 312. ↵

- Joyce A. Tyldesley, Cleopatra: Last Queen of Egypt (New York: Basic Books, 2008), 222. ↵

1 comment

Nisreen Jneik

Wow thats a great article. I love all the details and how in depth it is about Cleopatra and Antonys relationship.