During the 1800s, deaf people in America had no language they could use to communicate with other deaf people, or anyone else for that matter. They let others know their needs and wants through gestures and signs they came up with on their own. Some basic gestures, such as “yes” or “hungry,” were somewhat universal, but those signs only scratched the surface of what deaf people wanted to say. They were in need of their own language and of a way and a place to learn it, and although he was not deaf or hard of hearing, a man named Thomas Hopkins Gallaudet was the one who finally acquired it for them.

Thomas Gallaudet was a man of many talents. After graduating from Yale at seventeen, he worked as a law assistant and a tutor, but due to health-related issues, he left his job and became a door-to-door salesman in rural Kentucky and Ohio, where he schooled young children that couldn’t afford an education. He especially enjoyed teaching geography, U.S. history, and the Bible, which eventually lead to him discovering his own passion for religion. He earned his license to be a preacher, and became a traveling minister, going everywhere he felt there was a need. His constant traveling allowed him to visit his family in his hometown of Hartford, Connecticut on a regular basis.1

During one of his visits home, Gallaudet came across his neighbor’s daughter, Alice Cogswell, playing by herself. At the age of two, Alice had contracted meningitis, and as a result, lost her hearing.2 Her father, Dr. Mason Fitch Cogswell, explained to Gallaudet that his daughter was deaf and that she had trouble communicating with not only other children but also with her own family. Knowing that Gallaudet was a teacher, Dr. Cogswell pleaded with Gallaudet to help Alice learn how to speak, regardless of whether it was with her voice or her hands.3

Gallaudet agreed, and started teaching a simple form of sign language as best as he could. Nevertheless, both Gallaudet and Dr. Cogswell were deeply concerned with the lack of deaf education in America and set out to change that. The two them collected donations and support from their community, and soon enough, they had sufficient funds to send Gallaudet to Europe, to track down a sign language teacher.4

During his travels, Gallaudet came across an advertisement for a speech given by Abbe Sicard, the principal of a deaf institution in Paris, France. Gallaudet had previously known about him and his work, so he attended one of his speeches. After the speech, Gallaudet approached Sicard, and spoke to him about his troubles and worries over deaf education in America. Sicard listened intently to his woes and made the decision to invited Gallaudet to the institution he taught at, to take lessons under him. Gallaudet zealously accepted the offer, and went off to Paris with Sicard.5

In addition to taking classes with Sicard, Gallaudet also took private lessons with Sicard’s chief assistant, Laurent Clerc. Gallaudet was entranced by Clerc’s expertise in the sign language and begged him to come to America to teach with him. Clerc was skeptical, but Gallaudet was adamant. He worked hard to get Clerc onboard with his plan. Clerc eventually gave in and sought permission from Sicard to take a leave for his journey to America. Sicard was also initially wary of Clerc’s expedition, but also came around to the idea and granted Clerc the permission he asked for.6

On June 18, 1816, Gallaudet and Clerc set out for Hartford, Connecticut on the ship Mary Augusta, a journey that lasted fifty-two days. The two men used that time to exchange their knowledge of languages. Clerc continued teaching Gallaudet the vast array of signs that were included in French Sign Language, and Gallaudet helped Clerc to polish his English-speaking skills. On August 22, 1816, the day the Mary Augusta arrived in America, Laurent Clerc met Alice Cogswell for the first time. Although she did not know French Sign Language, Clerc “communicated with her through sign associations.” Clerc saw Alice had a strong will to continue to learn sign language, which fueled him in his quest to teach the deaf people of America a standardized nonverbal form of communication.7

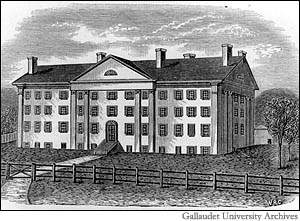

Over the next couple of months, Gallaudet and Clerc traveled the United States. They spread information about sign language and deaf culture, met with potential students and their parents, and they began the process of establishing the first deaf school in America. They collected funds by taking donations from the public and from the Connecticut General Assembly also. They raised over $15,000 and they used that money to start what was “originally called the Connecticut Asylum at Hartford for the Instruction of Deaf and Dumb Persons (now the American School for the Deaf).”8 On the day of April 15, 1817, a little less than a year since Gallaudet brought Clerc to the United States, the school opened its doors to the public. Laurent Clerc was the first teacher and Alice Cogswell was the first student. The French Sign Language Clerc taught to his students eventually evolved to the dialect that deaf Americans still use today, American Sign Language.9

Although the school was good, Gallaudet and Clerc wanted to keep going. They went to Congress and got approval from the House of Representatives, Senate, and President Abraham Lincoln to granted college degrees from their school. Eventually, the American School for the Deaf branched out to form Gallaudet University, the first and only all-deaf university in the United States.10 Both the American School for the Deaf and Gallaudet University continue to provide proper education to those who are deaf and hard of hearing, proving a saying that prevails in deaf culture: Deaf people can do EVERYTHING a hearing person can do except hear.

- Katalin Enders, “Gallaudet, Thomas Hopkins,” 2003, Learning to Give (website), https://www.learningtogive.org/resources/gallaudet-thomas-hopkins. ↵

- “Alice Cogswell,” Scholastic. April/May 2012. ↵

- Carolyn Ball, The History of American Sign Language Interpreting Education (Minnesota: Capella University, 2007), 11. ↵

- Loida R. Canlas, “Laurent Clerc: Apostle to the Deaf People of the New World,” 2015, Gallaudet (website), http://www3.gallaudet.edu/clerc-center/info-to-go/deaf-culture/laurent-clerc.html. ↵

- Margret A. Winzer, The History of Special Education: From Isolation to Integration (Washington D.C.: Gallaudet University Press, 1993), 101. ↵

- Margret A. Winzer, The History of Special Education: From Isolation to Integration (Washington D.C.: Gallaudet University Press, 1993), 101. ↵

- Loida R. Canlas, “Laurent Clerc: Apostle to the Deaf People of the New World,” 2015, Gallaudet (website), http://www3.gallaudet.edu/clerc-center/info-to-go/deaf-culture/laurent-clerc.html. ↵

- Loida R. Canlas, “Laurent Clerc: Apostle to the Deaf People of the New World,” 2015, Gallaudet (website), http://www3.gallaudet.edu/clerc-center/info-to-go/deaf-culture/laurent-clerc.html. ↵

- Marc Marschark and Patricia E. Spencer, Oxford Handbook of Deaf Studies, Language, and Education (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003), 13-14. ↵

- Loida R. Canlas, “Laurent Clerc: Apostle to the Deaf People of the New World,” 2015, Gallaudet (website), http://www3.gallaudet.edu/clerc-center/info-to-go/deaf-culture/laurent-clerc.html. ↵

61 comments

Caily Torres

This was a very informative and touching article! Gallaudet had a passion for teaching which lead to his motivation to create a language for people with a hearing disability. Life is harder for people with hearing disabilities because a small percentage of people know let alone use sign language. I can’t imagine how it was like for deaf people back when ASL wasn’t created. Even though Gallaudet wasn’t a part of the deaf community, he changed the future for people with a hearing disability for the better. There are restaurants, schools, and jobs that use ASL as their main form of communication. Gallaudet gave the deaf community a chance and opened up many opportunities for them.

Aaron Sandoval

This article was very informative, I personally have a cousin who is deaf and had to learn basic sign language to communicate, and always felt it should be more well known. This article did a good job of telling us about Thomas Hopkins Gallaudet and the crucial role he played in the creation of ASL. Articles like this are crucial in spreading important historical stories that would have otherwise been an endnote in history.

Madelynn Vasquez

Fantastic article! I’d heard about Gallaudet University before and the various all deaf schools offered throughout the country, yet I never once thought about how that became possible nor did I realize how important it is to be able to comment effectively, respectfully, and appropriately with the deaf community. It makes you realize that language has always transcended past the idea of just verbal. I, as an aspiring linguist, have always said that even if there is a language barrier, the human mind and human desire for wanting to build connections is stronger than such. We tend to find ways to communicate regardless and I think that being able to share an article on such a piece of history that is so important to a big community is great!

Yamilet Muñoz

Great article, I have always heard about Gallaudet University and the various all deaf schools offered throughout the country but I never once thought about how that became possible. It certainly puts to mind how easily school is for those of hearing and puts into perspective the need for more schools to offer proper lessons for those who are deaf. I hope this brings much-deserved attention to the deaf community.

Edith Cardona

It’s very interesting how the author of the article chose to include Thomas Gallaudet’s background and history before getting to the sing language portion, showing that anyone can help make a difference. It’s crazy but totally not unexpeceted that America didn’t really dedicate time to teaching deaf people sign language before this man.

Samantha Ruvalcaba

This was a very interesting read. The first thought that I had when reading that Gallaudet went to France seeking a teacher was, “But then he’d be learning French Sign Language… How could that translate to English?” Sure enough, they created a dialect that would be used in America. It’s truly fascinating how they made that possible and instinctively tried to find a means of communication.

Christopher McClinton

This is n article that kind of reminds of the piece we read Pinker. And the ways humans are able to communicate with people through certain expressions. This is why it is very important to learn about other cultures and their ways of communication. In this case with sign language this is universal. This clearly shows us how much we must educate our selves in the communication world in order to survive.

Cirilio Vivenza

This is a really enjoyable and insightful article about America’s foundation of sign language. I admire how this article tells Thomas Gallaudet’s background and recent pursuits, then emphasizes his ambitious path to find a way to create a way for the deaf to communicate in his own country. Thomas Gallaudet and many others like him are important figures to recognize for their perseverance and ambition, as it shows us that when we put our minds to something we care about and truly take an effort to create a system to serve those in need, the achievement will last as long as we do.

Victoria Salazar

This is truly an inspiring article. I am so glad that Thomas Gallaudet decided to take on the mission of teaching Alice how to communicate despite her being deaf and there being no language for deaf people at that time in America. What doesn’t make sense to be though is that today there is American Sign Language even though our sign language came from Europe and some aspects of the French culture. Lastly, I liked the little addition at the end of the saying that is prevalent in the deaf community. I thought it was neat.

Phoebe Dickinson Land

What a fascinating article! I must admit, coming from a position of privilege as an able-bodied person, the acquisition of sign language is not something I think about more so than a passing thought. It is easy to forget that so many do not have this luxury, as they so desperately need a means to communicate. As an immigrant, I always wondered what separated English Sign Language and American Sign Language, and I am sure this French input plays a crucial role. It is so easy to forget that, like spoken language, sign language must adapt across cultures to meet the needs of the people who use it. I would love to see further integration of the history of and practice of sign languages in our schools today.