Winner of the Fall 2018 StMU History Media Award for

Best Overall Research

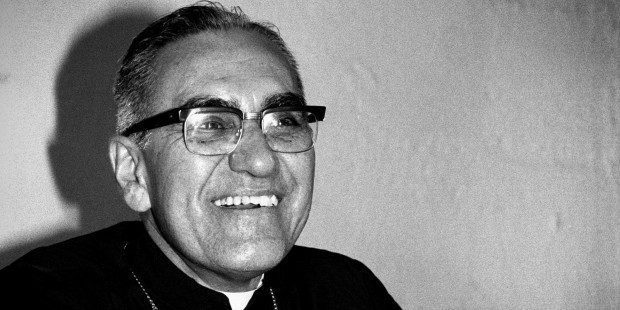

It was March 24, 1980. At 6:30 PM, Monsignor Oscar Romero was officiating his daily mass, just as any other day. Believers were lined up on the benches of the small hospital chapel, all absorbed by his passionate and defiant words. It was not long before their peaceful surrounding was violently disrupted by the deafening sound of a gunshot. They all looked around, screaming, wailing, roaring out the fear within them. Monsignor had been killed. A shot straight into the heart, and his body sank immediately to the ground.1 Without any notice whatsoever, El Salvador had witnessed the death of the most influential and brave man they had ever had: the man who would one day become the Saint of America.2

In the 1970’s, the decade previous to the war, many revolutionary groups were formed in opposition to the authorities. Many attempted coup d’états took place, as young people united to try to bring down the military authorities, who, in turn, responded to the uprising with violent suppression. Many were murdered as a result of their opposition, and many public massacres took place as tensions rose on both sides.6 The military had orders to murder anyone suspected of opposing the government. El Salvador had never found itself in such a bad position, and its citizens were all worried about their uncertain futures. Their lives were threatened by the hands of soldiers who would murder anyone, regardless of their age or gender. In the middle of that turmoil, however, one hero arose. One sole individual who was brave enough to stand up for those whose family members had been killed, and for all those whose human rights had been violated. Monsignor Romero knew that he had to fight for peace, in the name of God, even if this would cost him his own life.7

Nevertheless, Romero was anything but scared. He continued preaching that El Salvador badly needed God’s love, and insisted in the need for reconciliation between the two sides. For instance, in one of his homilies, he mentioned: “I would like to make a special appeal to the men of the Army: Brothers, you are from our own people, you kill your own peasant brothers and, upon an order to kill that is given by a man, must prevail the law of God which says: You shall not kill in the name of God…”9

As time went by, controversy arose in terms of monsignor’s fight for peace, and many developed hatred towards him and his preaching. Certain groups even believed that his preaching was simply about politics, and that they were causing even greater harm and worsening the conflict in the country. Romero, however, addressed this by saying that those people were forgetting that the church is simply “illuminating” the evil that exists in the world, not creating it, and that the “word of God wants to get rid of that evil.” Monsignor was no longer defending only the oppressed, but also his church and faith.10

In May 1979, Romero received a death threat from a group named “La Falange,” which was actually an arm of the authorities. They claimed that he was “at the head of a group of clerics who at any moment will receive about 30 projectiles in the face and chest.”11 On several other occasions, Monsignor received letters filled with violent accusations and threats. Anyone who spoke about him publicly was at risk of being killed by the soldiers, and all of those carrying a crucifix or a bible were equally exposed to murder because they showed evidence of supporting the Catholic views of peace that he preached.12

Overwhelmed by the fact that monsignor’s safety was at risk, Pope Paul VI reached out to him, and asked him “to be careful with what he said, because his mission was to be in harmony with the powerful class.” Monsignor bravely responded: “Saint Father, in El Salvador, denouncing justice is not being communist, it is a reclaiming of rights.”13 The pope even offered him an opportunity to abandon El Salvador and be transferred to any city or republic he desired for his own safety, but once again, Monsignor respectfully rejected this proposal and claimed that “he would never even think about leaving El Salvador.” The death threats against him continued to grow, and numerous priests, brothers, and bishops broke their relationships with him, for fear of being harmed themselves. In a matter of time, he was all alone.14

Monsignor had never imagined that those threats would one day become a painful truth. In March 24, 1980, he was officiating a mass, as he often did, in the Divine Providence Hospital chapel in San Salvador. During his homily, however, the most surprising event took place in a matter of seconds. A red Volkswagen appeared outside the church. The car stopped right before the front door, and an unknown individual made his way towards the back window. From there, thirty meters away from the altar, he held a rifle with a telescopic sight in his hands, pointed it in the precise direction at Romero, and fired. The bullet went straight into monsignor’s heart, drilling his main artery, and bringing him down to the floor, where he laid in his own blood while everyone around him watched in horror. He had been killed. The people in the church began wailing in fear, and rapidly ran towards him, hoping he was still alive. Some nuns that were present during mass took hold of him and did everything they could to help. But it was useless. One of them, however, stood aside, and began to pray. She knew that what had happened was a terrible tragedy, and she could not do anything better than drown herself in prayer.15

An audio of Monsignor Romero’s last homily. At second 52, the gunshot that killed him can clearly be heard. | Courtesy of Youtube

The next few days were of great alarm for El Salvador, as everyone received the news of the terrible event. All newspapers were displaying the details of the murder, and all were questioning who might have done something as terrible as that. It wasn’t until the 23 November, 1987, that a member of the national guard provided the name of someone he knew that had been involved in the murder of Romero: Álvaro Saravia. There was an investigation, and he was later found guilty of the murder, for which he was condemned to pay a 10 million fine to the priests’ family.16 Soon before his trial, however, he fled, making his escape and has been in hiding ever since, reportedly claiming that he is innocent of Romero’s murder and that he was not the only one involved in the crime. In several interviews, he declared that although he was, indeed, at the crime scene, it was not him who actually shot Romero.17 And to this day, no one has ever been able to find who killed Monsignor, despite all the investigations that has been done. Only one fact has been confirmed: the murder had been a “conspiracy between the government of El Salvador and a ‘death squad’, an extreme right-wing paramilitary group commanded by then-Army Major Roberto D´Aubuisson.”18 It was also discovered that the killer was given only $114 to carry out one of the most atrocious murders of Salvadorian history. Nevertheless, the proof as to who was paid to shoot Romero is still unclear, and so far, no one has been directly accused of his murder.19

A few days after the assassination, on March 20, 1980, a public funeral was held in his honor. The event was officiated in the metropolitan Cathedral of San Salvador, and it is estimated that around 250,000 people showed up. In the plaza, however, as the funerary commemoration was held, a huge explosion caused terror among the people. A bomb had been placed in the area, and people were being shot by snipers hiding around the zone. Approximately two hundred people were injured in the incident, and forty were killed. Clearly, Monsignor Romero’s preaching has continued to incite controversy, even after his unexpected death. Authorities were not happy with his impact and the admiration people felt towards him.20

However, it was his bravery and his tolerance that made Monsignor’s story reach the Vatican a few years later, in the 1990’s, when Archbishop Vincenzo Paglia decided that his life was worth considering for sainthood. He therefore solicited to the Vatican that Romero should be admitted into the process of beatification and canonization. Although his case was quite stagnant for a couple of years, in 2005, Pope Francis took greater interest in monsignor’s story, such that he could finally take the steps towards becoming an actual saint.21 According to the beliefs of the Catholic Church, there are five preliminary steps for one to be named a saint. To begin with, it is usually expected that five years must pass after the death of the individual before he or she can be considered for sainthood. After this, the bishop of the diocese where the person died opens a file and begins an investigation to verify that the person’s life was indeed holy and virtuous enough to be considered a saint. Then, the Congregation for the Causes of Saints evaluates the evidence that shows the impact of the person’s works, and his influence on other people’s religious lives. The next step involves verifying any miracles that have been made possible through their intercession. Once all of these steps have been made, the person can be beatified and finally canonized to become an official saint in the Catholic Church.22 Monsignor Romero’s case for sainthood traversed all of these steps, and on the 23 of May, 2015, he was finally beatified in an official ceremony held in El Salvador.23 The miracle that served to approve his sainthood was related to a pregnant woman, who was sick with a terminal disease. It was proven that after prayer to Romero for his intercession, the woman was healed and gave birth to a healthy baby.24

According to Pope Francis, Monsignor Romero will be officially named saint on October 14, 2018 in Rome, and there is no doubt that in El Salvador, people will stand proud with their heads up high, looking to heaven for their bravest man: the Saint of America.25

- Ismael López, “Monseñor Romero, vida y muerte del primer santo centroamericano,” LA PRENSA, March 11, 2018, https://www.laprensa.com.ni/2018/03/11/suplemento/la-prensa-domingo/2388833-monsenor-romero-vida-y-muerte-del-primer-santo-centroamericano. ↵

- Cristina Cabrejas, “El papa Francisco canonizará a “El Santo de América,” Oscar Arnulfo Romero,” infobae, March 7, 2018, https://www.infobae.com/america/america-latina/2018/03/07/el-papa-francisco-canonizara-a-el-santo-de-america-oscar-arnulfo-romero/. ↵

- Ignacio Martín Baró, “La guerra civil en El Salvador,” Biblioteca P. Florentino Idoate, S.J. Universidad Centroamericana José Simeón Cañas, http://www.uca.edu.sv/coleccion-digital-IMB/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/1981-La-guerra-civil-en-El-Salvador.pdf. ↵

- Rodrigo Noyola and Jaime Mancía, “Dictadura Militar Cafetalera,” Litasal (2005), https://www.listasal.info/articulos/dictadura-militar.shtml. ↵

- Historia de El Salvador, (El Salvador: Ministerio de Educación de El Salvador, 2009), 16, https://www.mined.gob.sv/descarga/cipotes/historia_ESA_TomoII_0_.pdf. ↵

- “1979: El Salvador cathedral bloodbath,” BBC News, http://news.bbc.co.uk/onthisday/hi/dates/stories/may/9/newsid_2520000/2520219.stm. ↵

- “El Salvador El espectro de los «escuadrones de la muerte»,” Amnestía Internacional (1996), https://web.archive.org/web/20060303063256/http://web.amnesty.org/library/index/eslAMR290151996?open&of=esl-slv. ↵

- “Oscar Arnulfo Romero,” Biografías Y Vidas, https://www.biografiasyvidas.com/biografia/r/romero_oscar.htm. ↵

- Ismael López, “Monseñor Romero, vida y muerte del primer santo centroamericano,” LA PRENSA, March 11, 2018,https://www.laprensa.com.ni/2018/03/11/suplemento/la-prensa-domingo/2388833-monsenor-romero-vida-y-muerte-del-primer-santo-centroamericano. ↵

- Monseñor Oscar Romero, “La Reconciliación de los Hombres en Cristo, Proyecto de la Verdadera Liberación,” SISCAL (1980), http://www.sicsal.net/romero/homilias/C/800316.htm. ↵

- “El martirio de monseñor Romero,” CUBADEBATE, February 5, 2015, http://www.cubadebate.cu/especiales/2015/02/05/el-martirio-de-monsenor-romero/#.W6cTRmhKjIW. ↵

- “La noche en que mataron a monseñor Romero: entrevista con el hermano del mártir,” Prensa Libre, May 22, 2015, https://www.prensalibre.com/la-noche-en-que-mataron-a-monseor-romero-entrevista-con-el-hermano-del-martir. ↵

- “La noche en que mataron a monseñor Romero: entrevista con el hermano del mártir,” Prensa Libre, May 22, 2015, https://www.prensalibre.com/la-noche-en-que-mataron-a-monseor-romero-entrevista-con-el-hermano-del-martir. ↵

- Tomás Andréu, “’Yo sabía que iban a matar a monseñor Romero’: los recuerdos de Gaspar Romero, el hermano del obispo mártir de El Salvador que será hecho santo por El Vaticano,” BBC News, March 7, 2018, https://www.bbc.com/mundo/noticias-america-latina-43321774. ↵

- Ismael López, “Monseñor Romero, vida y muerte del primer santo centroamericano,” LA PRENSA, March 11, 2018,https://www.laprensa.com.ni/2018/03/11/suplemento/la-prensa-domingo/2388833-monsenor-romero-vida-y-muerte-del-primer-santo-centroamericano. ↵

- Carlos Dada, “Así matamos a monseñor Romero,” Elfaro, March 22, 2010, https://www.elfaro.net/es/201003/noticias/1403/. ↵

- “Entrevista Álvaro Saravia, implicado en el asesinato de Monseñor Romero,” Redes Cristianas, (2006), http://www.redescristianas.net/entrevista-a-alvaro-saravia-implicado-en-el-asesinato-de-monsenor-romero/. ↵

- “Vaticano revela detalles del asesinato de Monseñor Romero en El Salvador, 38 años después,” Aristegui Noticias, March 25, 2018. https://aristeguinoticias.com/2503/mundo/vaticano-revela-detalles-del-asesinato-de-monsenor-romero-en-el-salvador-38-anos-despues/. ↵

- Félix Población, “Al arzobispo Óscar Arnulfo Romero lo mató un sicario por 114 dólares,” Evangelizadoras de los apóstoles, (2011) ,https://evangelizadorasdelosapostoles.wordpress.com/2011/03/21/al-arzobispo-oscar-arnulfo-romero-lo-mato-un-sicario-por-114-dolares/ ↵

- Ismael López, “Monseñor Romero, vida y muerte del primer santo centroamericano,” LA PRENSA, March 11, 2018,https://www.laprensa.com.ni/2018/03/11/suplemento/la-prensa-domingo/2388833-monsenor-romero-vida-y-muerte-del-primer-santo-centroamericano. ↵

- Cristina Cabrejas, “El papa Francisco canonizará a ‘El Santo de América,’ Oscar Arnulfo Romero,” infobae, March 7, 2018, https://www.infobae.com/america/america-latina/2018/03/07/el-papa-francisco-canonizara-a-el-santo-de-america-oscar-arnulfo-romero/. ↵

- “How does someone become a saint?” BBC News April 27, 2014, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-27140646. ↵

- Ismael López, “Monseñor Romero, vida y muerte del primer santo centroamericano,” LA PRENSA, March 11, 2018,https://www.laprensa.com.ni/2018/03/11/suplemento/la-prensa-domingo/2388833-monsenor-romero-vida-y-muerte-del-primer-santo-centroamericano. ↵

- “Esta es la fecha de canonización de Monseñor Romero y Pablo VI,” ACI Prensa, May 19, 2018, https://www.aciprensa.com/noticias/pablo-vi-y-oscar-romero-seran-canonizados-el-14-de-octubre-en-roma-95969. ↵

- “Esta es la fecha de canonización de Monseñor Romero y Pablo VI,” ACI Prensa, May 19, 2018, https://www.aciprensa.com/noticias/pablo-vi-y-oscar-romero-seran-canonizados-el-14-de-octubre-en-roma-95969. ↵

113 comments

Geremy Landin

It was around the time that Romero was beatified that I heard of his story. He is an admirable individual and now an admirable saint. There are people in this world that do what is necessary because there is nothing else that should be done. Romero changed the lives of El Salvadorians and of every Catholic person thereafter. He continues to change the lives of everyone else that lives in freedom and without fear. Romero is another shining light. He is another beacon of hope. His story, like that of Mercedes Sosa, of Emma Tenayuca, of activists and luchadores alike, will continue to shake the grounds under the powerful. It is sad that things like this have to happen for change but the impact is everlasting. This article takes you back to the site. The reader is standing in the church and can hear the words. Spanish-speaking or not, the power of Romero’s last words can be understood; a life of perseverance and truth can lead to an eternal life that encompasses truth and virtue. Que viva Oscar Romero, El Santo.

Antonio Coffee

I think that what Oscar Romero did was amazing. He put his life on the line even though he knew that it was dangerous and it could end up with him being arrested or killed. Unfortunately, he did end up being killed but in the time before this happened, he was able to be a beacon of hope to the people and it was great that he was finally made into a saint.

Leonardo Gallegos

I admire Oscar Romero because although he knew the consequences that his movement brought, he kept firm knowing that his death was soon to come. When the pope offered Romero to move away from El Salvador and Romero rejected the death threats kept growing but he stayed firm and loyal for the justice of his country, which is something I truly respect tremendously. Great read!

Michael Leary

Very well written article about one of the great American saints, Oscar Romero. I had known somethings about his life and ministry for peace, but, had not read a lot of the material provided, for example, I did not know that he was offered the opportunity to leave and declined the opportunity. I found the way that he was threatened comparable to what Pope John Paul II went through when he helped bring down communism in Poland.

Gabriel Cohen

Hey Daniela, great article and a well deserved win! I’m not surprised at the high quality of your writing after working with you last semester. You did a brilliant job of making a biographical text accessible and relevant to a modern audience. It’s often difficult to mingle political and religious material, but you did so with great clarity.

Edgar Velazquez Reynald

I didn’t know that Monsignor Romero became a saint! This was a very well written article that was able to give us historical and political context to help us understand what Romero was fighting for. Romero believed in doing the right thing so much that he declined the Pope’s aid for himself. The writer does a great job in giving us exposition without it being heavy handed. The narrative arc more than delivers in telling the story of a man who is saint.

Mario Sosa

Good work on including the military conflicts in El Salvador during the 1970’s, as it helps show the state of the country during Romero’s ministry. I have heard of Romero’s assassination before but I was unaware of the mass shooting that took place at his funeral. One thing that I still wonder about is for how long after Romero’s assassination did the military persecute those who followed him? Overall excellent job on the article!

Lindsey Wieck

Daniela, this piece is so-well researched and thorough in its writing. You do an excellent job at situating his life and his murder within its social, political, and religious context. This is now a required reading in my graduate Advanced Public History methods course.

John Cadena

Having just completed chapter 2 of Jack Hart’s Story Craft, I found myself focusing on the five areas of structure which make up a stories arc as I read through this piece. Perfect for this was being able to recognize the use of rising action in this article. The excellent use of chronologically connecting the mystery which would come later in the story. Without a doubt, the words of Ted Conover did not go astray in this article, when he said, “a narrative is when things go wrong.” (Hart, 30)

Scott Sleeter

A great article on a tragic story that needs to be told to future generations. The history of Central America in the 1980s is slowly being forgotten. Heroes like Monsignor Romero need to be remembered for their contributions in the fight against injustice. He was a brave soul who stood alone to do what was right. He is deserving of the sainthood which he has been honored. Hopefully his life and his death will inspire others to stand up for what is right even in the face of death.