The year was 1828, and South Carolina was dying in the sweltering heat of August. The paved roads that had once provided excellent transportation to traders and tourists alike were altogether abandoned, helplessly desolate besides the occasional passerby. Her dockyards, once teeming with shipbuilders and trading companies, became little more than wooden dust collectors. It was only a few months after Congress had pushed their infamous “Tariff of Abominations” to the States, but the Palmetto State was already suffering. The reason was simple: the bill had destroyed all incentive for foreign nations to trade with the Southern States. This destruction of incentive was no accident. Indeed, the “Tariff of Abominations” was created with one goal in mind: to specifically discourage foreign trade to and from the United States. It was certainly effective in that regard, and it worked by drastically raising the American tax on imported foreign goods. This, in turn, destroyed the economy of the Southern states, who made the majority of their income by trading with nations like Great Britain and France.1

There was perhaps no State greater affected by the tariff than South Carolina. South Carolina was, prior to the adoption of the tariff, a state that relied primarily upon foreign trade to keep its very government in operation. Without European economic support, every state in the South was forced to buy all of their products from Northern manufacturers, who used their artificial monopolies to attack and dominate the Southern economy.2 The Northern states, on the other hand, received nothing but benefits from the effects of the “Tariff of Abominations.” Ironically, the non-slave holding States effectively chained up and forced their slave-holding counterparts into economic slavery. Southern businesses, because foreign nations refused to trade with them, quickly collapsed into financial ruin. The few Southern firms that remained were thoroughly abused by their Northern neighbors, who used their newfound monopoly to force states like South Carolina to sell their cotton and other raw products to the North at dirt cheap prices. The few jobs that were offered to citizens of Southern states quickly evaporated, and with them, so too did the various small businesses. As time went on, the Southern states grew increasingly restless. Standing president John Quincy Adams, the man who had signed the bill into law, almost refused to speak on the matter in fear of jeopardizing his upcoming bid at reelection—a reelection, that, with Adams’ expansive northern influence, was almost certain. The Southern States, it seemed, were cursed to suffer in silence.

Or, rather, it certainly seemed that way. All was not lost for the people south of the Mason-Dixie line, as former war hero Andrew Jackson had just announced his appearance into the presidential race! The war hero’s reappearance did not come as a surprise to many Americans, as Jackson’s friends had spent the last four years convincing voters that the previous election, the election of 1824, was concluded on the basis of a “corrupt bargain” between Adams and the Speaker of the House, Henry Clay. The controversy emerged from the fact that the House, not the electoral college, had to decide the winner of the election, due to the lack of a clear winner.3 The Jacksonians believed that John Adams was elected by the House in an unfair manner, as Jackson himself had received the most electoral votes. Nevertheless, Old Hickory was determined to not let the same mistake happen twice. This time, in 1828, he had a trick up his sleeve: the horrible state of the South. He decided to capture the Southern states by promising them a huge reduction in tariff rates, and a return to the tariff rates that had previously made them wealthy.4 Eager to prove his absolute devotion to the Southern people, Jackson even went so far as to adopt John C. Calhoun, a popular figurehead in South Carolina, as his vice president. With his southern support secured, and his “corrupt bargain” scandal in the national headlines, Jackson’s presidential election was all but guaranteed, and he easily defeated Adams.

The first few months of President Andrew Jackson’s election were absent of any discussion of the tariff. South Carolina and the rest of the Southern states refused to give up hope, and still believed in the President’s campaign promises. As the days turned into months, however, they began to lose faith. While Adams still held the executive office, Jackson’s sudden silence on the matter worried his Southern supporters. Much to the satisfaction of Jackson’s northern voters, he continued to sit on the issue of the tariff, unwilling to even speak on the matter. John C. Calhoun decided to push on without Jackson, and, on one of his frequent trips to South Carolina, decided that South Carolina had suffered enough. Rather than wait for Jackson to adopt the tariff as a topic of discussion once more, Calhoun was forced to take matters into his own hands. The politician refused to stand by and watch his home state suffer without representation any longer.5 Calhoun quickly found himself in a very peculiar situation. On one hand, he knew that openly betraying Jackson’s trust would be equivalent to political suicide. He could lose his bid at the vice presidency, and, even worse, he could lose all of his influence in the Federal government. On the other, he understood that the people of South Carolina were counting on him to fix the tariff problem. If he did nothing, he would be betraying both his people and his entire way of life. After weighing his options, Calhoun eventually decided to follow the examples of the founding fathers when they defended the Constitution. He resolved to speak up in defense of South Carolina, but, to stay one step ahead of his political opponents, he would defend them anonymously. Freeing himself from the weights of political responsibility, Calhoun picked up his pen against the Federal government, and drafted a document that would eventually threaten to rip the nation apart.

Calhoun finished drafting his magnum opus, the South Carolina Exposition and Protest, in December of 1828. The importance of the Exposition that Calhoun had poured his heart into cannot be understated; the Nullification Crisis could not hope to succeed without it. Ironically enough, its core ideas, and indeed its power, did not directly originate from the Vice President himself. Calhoun, because of his obsession with eighteenth-century literature, realized that the “Tariff of Abominations” problem attacking South Carolina had already been solved by the founding fathers of the United States. Indeed, most of his Exposition would center around the adoption of the “nullification doctrine” expressed and endorsed by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison in their Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions.6

Although Thomas Jefferson and James Madison were the first published advocates of the doctrine of nullification, they did not invent the idea themselves either. No, the doctrine of the concurrent majority and the ideas behind nullification, though redefined by Calhoun, were as old as the original thirteen colonies themselves. Nullification, in its purest form, is simply another check upon the Federal government of the United States. Supporters of the doctrine believed that the states had the right to “veto” mandates from the Federal government, just like the President has the right to “veto” acts of congress. The doctrine, in practice, would allow the several states to nullify, or veto, any Federal mandate that they deemed unconstitutional. At a time when any state could effectively secede from the Union, Calhoun believed that the doctrine could efficiently prevent secession, civil war, and Federal tyranny. Nullification, Calhoun noted, would also finally allow the people of South Carolina and the South to rid themselves of the “Tariff Abominations.”7

With his Exposition finally complete, Calhoun made an extra effort to keep his identity a secret as he sent the document to the government of South Carolina, right under the nose of his own Party. The State legislature looked favorably upon the doctrine, and it would eventually become so popular within South Carolina’s government that the legislative body would print over 5,000 copies of it. After some debate, however, South Carolina’s legislature ultimately decided that it would continue to believe that Jackson would uphold his promises, despite his newfound silence on the topic. The people of South Carolina believed that adopting such a controversial doctrine would destabilize the relationship between the South and the Federal Government. Although Calhoun’s “Protest and Exposition” had failed to move the government of South Carolina, it wouldn’t die there.8

By January of 1830, the small fire of nullification had evolved to an inferno—an inferno that would quickly smash into the United States Senate. It was a cool morning in January, and the senators were preparing to debate over the independent sovereignty of the Western territories, specifically their right to address the issue of slavery. An argument quickly emerged, and, as it escalated, one senator brought up the doctrine of Nullification right in front of Calhoun, who was overseeing the debate. Thus, what originally began as a simple debate over slavery in the Western territories rapidly grew into a full-fledged debate over the very nature of the American constitution as a whole. At the center of it all were two senators, Robert Haynes and Daniel Webster. Haynes, a Democratic-Republican of South Carolina, stood in the defense of the doctrine of Nullification, and Webster, a National-Republican from Massachusetts, argued against it.9 Calhoun couldn’t believe his ears: the doctrine of nullification was not only being debated right in front of him, but the senators were specifically referencing his “Protest and Exposition!” The Vice President refused to do nothing but watch as his brainchild was viciously attacked. After the first day of the debate, he sought out the defenders of the doctrine and, in private, began extensively tutoring them on the subject. Throughout the argument in the Senate, Calhoun would send senator Haynes and his friends a stream of handwritten letters elaborating on the points that he made in his now-famous Exposition. With their newfound confidence, the defenders of nullification began to strike back at Webster and his group of senators. Thus, the most celebrated debate in the Senate’s history erupted. The epic clash lasted longer than an entire week, and reached into every corner of the Senate. The debate stood alone in its importance, and it threatened to tear the entire legislative body apart at the seams. No senator could escape the awesome gravity of the situation, and every single one of them were dragged into it regardless of their individual party or political ideology.10

As the conversation around nullification grew louder and louder in the south, President Andrew Jackson was forced to act upon the promises he had made to the southern people almost four years prior. As a tribute to the people he had largely ignored for four years, he signed the Tariff of 1832 into law in July 14. Although the bill was certainly a step in the right direction, many poor, broken Southerners felt wholly betrayed by their Federal Government. Perhaps they had a right to feel that way, however, as it had taken their government over four years to reduce the duty imposed by a measly 10 percent, from 45 to 35. South Carolina could wait no longer. The States’ Rights party rapidly gained power within the Palmetto State, and, after gaining the majority edge over their centrist alternatives, called a state convention over the doctrine of nullification and its interpretation. Unsurprisingly, and by a vote of 136 to 26, the “South Carolina Ordinance of Nullification” was officially enacted into law on November 24, 1832. The government of South Carolina had effectively nullified the tariff, and, as far as its citizens were concerned, it no longer existed.11 John C. Calhoun, upon receiving word from the South Carolina legislature, ultimately realized that he could not both defend his brainchild in the Senate and hold his position as the Vice President of the United States. In addition, he was also plagued by the consequences of his infamous stance against the Federal government, including being dropped as Jackson’s running mate from the upcoming presidential election. After weighing his options, Calhoun ultimately saw only one way forward. So it was that John C. Calhoun would be the first Vice President in the history of the United States to officially resign from office. He left his post in December to become a senator for South Carolina, so that he could fight against the senators wishing to end nullification for good. South Carolina, in the meantime, was readying for war. Its government used the little funds it had to buy up a large collection of arms, and it raised a volunteer army of 25,000 people in just a few months. Everyone in South Carolina was on guard, for they were all too aware of the severity of their decision to challenge the Federal government. Although they acknowledged that the Federal government would not take kindly to active resistance against its laws, they were nonetheless ready to die for their right to self governance.

South Carolina was right to be wary, for when the news of South Carolina’s decision reached the ears of President Andrew Jackson, he immediately responded by sending warships to Charleston harbor. After only a few months, Jackson succeeded in getting Congress to pass the “Force bill,” a law that officially gave him the ability to make war on South Carolina if they failed to readopt the tariff.12 The entire nation held its breath, for no one knew just who would blink first: Jackson or Calhoun.

As it turns out, the Vice-President-turned-senator cared too much about his state to see it go to war with the entire Union. While Jackson and South Carolina were readying for war, he was busy drafting the “Compromise Tariff of 1833” with his friends in the Senate. South Carolina was not going to be dissolved quietly. The citizens of South Carolina immediately got to work building defensive forts, issuing blue uniforms to the various militias, and even began training in the streets, eager to keep Jackson’s forces from occupying even an inch of soil. At the same time, the government of South Carolina mirrored its people–and was readying for war by organizing the various militias into different regiments and reaching out to neighboring states for economic and military support.13 On the other side of the border, Andrew Jackson was already hard at work drafting up plans to take South Carolina by storm. His plan involved the capture of Columbia, the capitol of South Carolina, by any means necessary. Every reporter in the nation flocked to South Carolina as the people of the United States looked on in horror. At the center of it all stood John C. Calhoun and Henry Clay, two men willing to do anything to prevent a great American tragedy. They worked like madmen, feverishly revising and editing their “Compromise Tariff” in an attempt to get it passed through Congress in time. In constructing the Compromise Tariff to receive a majority vote in Congress, the two friends frequently sought the advice of their fellow senators. In this way, they were able to create a document that balanced the needs of the Federal government with those of South Carolina. Calhoun knew that failure to pass the bill through Congress would spell the death of thousands of men, each of whom had done nothing to warrant such a horrible and pointless death. To make matters worse, Calhoun had only adopted the doctrine of nullification to save the State that he held so close to heart. The very thing he had worked so hard to prevent was quickly becoming a reality. Calhoun would, in saving South Carolina from the fires of economic depression, condemn the State to the fires of war. If he failed here, he would have to live with the Shakespearean idea that he had destroyed his beautiful home by trying to save it.

As Jackson’s army finished lining up on the borders of South Carolina, Calhoun finished his second greatest piece of literature, a compromise between the Federal government and the people of South Carolina. As the new tariff was signed into law, Jackson hesitated, wanting to view the reaction from South Carolina before using military force. Nothing could stop Calhoun as he charged for South Carolina, hell-bent on informing the state of the existence of a compromise tariff as soon as physically possible. He finally reached the legislature, and, after throwing open the doors to the State legislature, presented the new tariff to the body of men who would soon shape American history forever. The various politicians within South Carolina knew all too well that a rejection of the compromise could thrust the Union into perpetual chaos. After hastily reviewing the tariff, the government of South Carolina officially adopted the new tariff, ending the Nullification Crisis once and for all.14

Some years later, as Andrew Jackson was exiting a carriage, a reporter asked if he had any regrets on his actions during the crisis. To the reporter he replied, “After eight years as President I have only two regrets: that I have not shot Henry Clay or hanged John C. Calhoun.”15

- William Freehling, Prelude to Civil War: The Nullification Controversy in South Carolina, 1816-1836 (New York: Harper & Row, 1965), 361-362. ↵

- William Freehling, Prelude to Civil War: The Nullification Controversy in South Carolina, 1816-1836 (New York: Harper & Row, 1965), 361-362. ↵

- William G. Morgan, “John Quincy Adams Versus Andrew Jackson: Their Biographers And The “Corrupt Bargain” Charge,” Tennessee Historical Quarterly, No. 1 (1967): 21, 44-46. ↵

- Encyclopædia Britannica, March, 2013, s.v. “United States Presidential Election of 1828,” by Alison Eldridge. ↵

- Margaret L. Coit, John C. Calhoun (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1950), 160-161. ↵

- Caleb William Loring, Nullification, Secession, Webster’s Argument, and the Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions: Considered in Reference to the Constitution and Historically (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1893), 90-91. ↵

- John C. Calhoun, Union and Liberty (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund Inc., 2014), 252-253. ↵

- Fredric Bancroft, Calhoun and the South Carolina Nullification Movement (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1928), 48-49. ↵

- Herman Belz, The Webster-Hayne Debate on the Nature of the Union. (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 2012), 3-34. ↵

- Caleb William Loring, Nullification, Secession, Webster’s Argument, and the Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions: Considered in Reference to the Constitution and Historically (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1893), 90-91. ↵

- Paul Leicester Ford, The Federalist: A commentary on the Constitution of the United States by Alexander Hamilton, James Madison and John Jay edited with notes, illustrative documents and a copious index by Paul Leicester Ford (New York : Henry Holt and Company, 1898), 1-5. ↵

- William W. Freehling, The Road to Disunion (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), 282. ↵

- William Freehling, Prelude to Civil War: The Nullification Controversy in South Carolina, 1816-1836 (New York: Harper & Row, 1965), 275-276. ↵

- H. Newcomb Morse, “The Foundations and Meaning of Secession,” Stetson Law Review 15, no. 2 (1986): 422. ↵

- Jon Meacham, American Lion: Andrew Jackson in the White House (New York: Random House Trade Paperbacks, 2009), 26-27. ↵

90 comments

Dylan Vargas

I like the article, not as much as others but it is a good and informed article. It gives up the issue of the early time like the “Tariff of Abominations” and what the people’s responses were. Also what they did to try and get it switched, even voting for a president who promised to change it. Also the story of how long it took to get it changed and why it took so long. Also, the effects of the change to the states are what makes this article good as well. The details behind everything, that is what captures the attention and give off good information.

Amelie Rivas-Berlanga

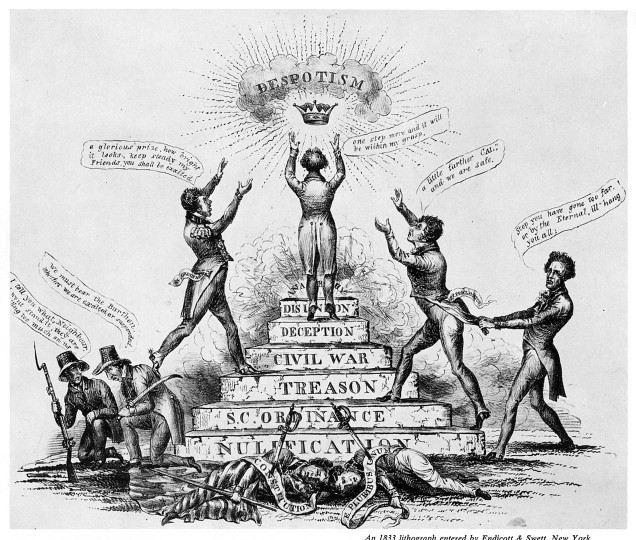

This article was super informative. It flowed well and was easy to read. It was a great topic to pick because the Nullification Crisis is a drama-filled event. The pictures were a good addition. The introduction is really good it gives the reader enough information about what happened that led to everything else. The Nullification Crisis is a really important topic because it could have led to a completely different outcome.

Seth Roen

The Nullification Crisis showed how fragile the young republic was and still struggled to figure out how to govern the nation. We almost had a civil war nearly three decades earlier, or that may have only been the first. Jackson was a mixed president, doing both good and bad actions during his administration. One of his good acts was the prevention of civil war and strengthening the Federal Government positions.

Aaron Onofre

That was a great article and it was written very well. The thing that stood out to me when reading this article was John C. Calhoun’s passion and love for South Carolina. He was so passionate that, first he wrote a doctrine of nullification in order to save his beloved state and then that same passion and love for his state led him to resign from the vice presidency, in order to defend his state. I commend Calhoun’s awareness to know when to come to a compromise and not to be so passionate that he would lead his state to destruction.

Marycarmen Sanchez

I loved how you put thing into perspective for the reader, you walked us through the events nicely. I was pretty surprised to learn, both in class and in this article, that the other Southern states didn’t defend South Carolina. In a time when almost everything was separated, I was extremely surprised that nobody came to their rescue before the compromise was written. Thank you for keeping the images informative and caught up with the article.

Jourdan Carrera

The author does an excellent job in showing just how close this crisis took us to the brink of war. A civil war, although a civil war on a much smaller scale, but a civil war nonetheless. I personally did not know about this crisis until this year and I was happy to learn even more about it when it came to this article, especially to get to learn about just how close we really did come to having a civil war style war this early in out history.

Ariette Aragon

Very well written article. I really liked how in-depth your writing is and how you thoroughly explained the events of the Nullification Crisis. It is incredible how close the United States was going to go into a civil war because of this tariff; it seems like the country has been and is always in conflict with each other or with other countries. Also, the images you provided were very good and relevant.

Matthew Gallardo

This article’s way of writing hooked me in at the start, and kept me reading. there was enough political intrigue to make a novel on John C. Calhoun. When it came to nullification, at first I didn’t have much interest in the subject. however as I got drawn in, from the crumbling South Carolinian economy to the promises that president Jackson never came through on, I became more interested in the story. I’m glad this reading was assigned, as it gave me a lot of information into something important that I was not interested in, yet fundamentally important to how relations work between the states and the government.

Aidan Farrell

This was a very well done article, Greyson. I did not know a lot about the nullification crisis, besides what we learned in class, but this article did a good job teaching about it. You really did deep into the crisis and what happened, which i appreciate. I love your word choice, and the article length really helped get the detail in. Well done.

Tyler Pauly

I really enjoy how in-depth this article was and how you were able to capture the emotions of all the parties involved. I find it very interesting that Jackson relied on the south to secure his election to be president, but did little to actually make sure their needs were met once he took office. If something like this happened today, I can only imagine how big a story it would be. I think sometimes we forget that there have been massive problems within our government in the past, and that maybe it isn’t as bad as it seems now.