The sounds of people shouting and jeering shook her from her haze as she realized what the day would bring. The sound of footsteps echoed down the hall, keys jingled as they were removed from a belt, and the sound of the lock clicking open finalized the peaceful moments of freedom before she was forced to stand and begin her walk to the center of town. The walk was overshadowed by the taunts of the common people and the force with which she was pushed to walk faster. Eventually, she reached the center of Paris where her fate stared back at her impassively. Standing straight ahead and looming taller than her, the simple yet intimidating form of the guillotine signified the end of Marie-Olympe de Gouges.

Marie Gouzes, more commonly known as Marie-Olympe de Gouges, was born in Montauban, France on December 31, 1748. She was the daughter of Anne Olympe Moisset and an unknown man. Many rumors surrounded who the mystery father could be: was it Pierre Gouzes, the husband of Anne Moisset, or Marquis Lefranc de Pompignan, a man of high social rank with whom Anne had a brief affair? Regardless of her paternity, Olympe resided with Pierre Gouzes until his death in 1750. She was known for her rebellious nature, which would continue well into her adulthood. In 1765, Olympe married Louis Aubrey, a French officer who was quite a few years older than she. Two years into their marriage, she bore a son and, a year later, Aubrey died. Staying true to her rebellious nature, Olympe de Gouges refused to be positioned as a widowed mother or remembered as the “Widowed Aubrey”; additionally, she vowed to never remarry. Around 1770, she abandoned her son and relocated to Paris in the hopes of gaining fame as a writer. There, she assigned herself the name Olympe de Gouges as a combination of her mother’s and father’s names.1

To establish herself, Olympe allegedly started or perpetuated rumors of her illegitimacy as the daughter of Marquis Lefranc de Pompignan, who was himself an established author and social elite. Even with the lack of proof, these rumors gained attention and status among the social elite in Paris, allowing Olympe to jump-start her writing career. While she climbed higher in Parisian social circles, Olympe began writing and publishing plays, novels, and pamphlets that focused on political and social issues that she deemed important. However, her successful climb in social status did not extend to her writing. As a playwright, her writing was described as slow-moving and loquacious, presumably as a result of her astoundingly simple education, which is only evidenced by her ability to sign her marriage certificate. Her written works, especially her plays, never gained public attention until 1785, when her first comedy, Le Mariage inattendu de Cherubin, was performed in the Theatre Français.2 Following quickly, Olympe wrote L’Homme Genereux, which never gained enough support to be produced for the stage, and L’Esclavage des Noirs, which was initially accepted for the stage until the reveal of Olympe’s gender, which led to the subsequent shelving of the playwright.3 Each of her writings focused on a social issue from the perspective of both extremes in a way she hoped would promote change in a method that would not destroy social stability. Le Mariage inattendu de Cherubin was written as a sequel to the 1784 play by Pierre Beaumarchais, The Marriage of Figaro, and her play focused on how a privileged husband’s crime affected the family and the victim. L’Homme Genereux showcased the political powerlessness of women and the injustice of imprisonment for debt, while L’Esclavage des Noirs explored the inhumanity of slavery from the first-person perspective of a slave.4 As the political turmoil in France reached a boiling point, Olympe’s focus shifted to human rights, especially the rights of women and children, and she attempted to maintain a moderate financial stance in the hopes of salvaging political stability.

On May 5, 1789, the Estates-General was called to Versailles to discuss grievances and possible solutions for the financial unrest in France.5 The Estates-General was an assembly of 1,200 representatives from the clergy (300), the aristocracy (300), and the commoners or Third Estate (600) elected to listed grievances and requests, also called cahiers de doléances, which would be presented before the king. When discord surrounding the voting of the estates arose, the Third Estate absconded from the group, renamed themselves the National Assembly, and threatened to proceed without the other estates. The National Assembly’s disruption resulted in the famous Tennis Court Oath, which became an agreement between all three estates, now officially titled the National Constituent Assembly, that they would not leave Versailles until they had created a new constitution for France.6

Hoping to prevent an outbreak of violence, Olympe de Gouges published a letter to the people urging a reconciliation with the king. She proposed that the people pay a voluntary tax that would work to stabilize the financial crisis. Olympe appealed to the public on two levels: the first level proposed paying the voluntary tax placed the common people on an equal placement with the aristocrats, while the second level stated that paying the tax would label the people as the king’s children. As the king’s children, the public would be responsible for preserving the emotional integrity of the state and monarchy which would, in turn, earn the king’s gratitude and recognition once the financial crisis was averted. Simultaneously, Olympe de Gouges appealed to the king and queen with the request that a luxury tax be placed on the aristocracy to alleviate the financial burden placed upon the Third Estate.7 Throughout her advocation for social reforms and taxes, Olympe de Gouges maintained her stance as a royalist by advocating the monarchial government be transformed with little violence into a constitutional monarchy that would focus on the voice of the people rather than the desires of the aristocracy. In 1788, Olympe produced a small, written piece entitled Droits d’une femme, which expressed her revolutionary beliefs, including a list of grievances against the aristocracy, but also maintained her allegiance to the monarchy in a regent government where the king held constitutional power instead of absolute power. This written work was different than her Declaration of the Rights of Woman and the Citizen, but offered the basic outline that she would later use to write her declaration. Her allegiance to the monarchy remained through the storming of the Bastille, which took place on July 14, 1789. But her support of the monarchy wavered in June of 1791 when King Louis XVI, Queen Marie Antoinette, and their family attempted to escape Paris to avoid the chaos and violence directed towards them. Because of their attempted escape, Olympe de Gouges’ rhetoric and political works became more pointed and supportive of the revolutionaries in the hopes of equality for men and women.

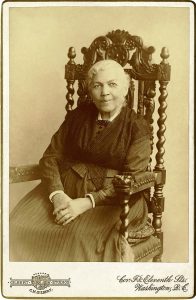

Courtesy of Wikipedia

As she worked on her political works, Olympe de Gouges often met and discussed social reforms with aristocratic women in social clubs that focused on supporting women’s rights within the revolution. The social clubs proposed reforms that would allow complete legal equality for men and women, create more job opportunities for women in the public sphere, better education for young girls, and a national theater dedicated only to plays written by women.8 One social club that Olympe was a part of was the Society of Republican and Revolutionary Women, whose members encouraged Olympe to write a document that would essentially serve as a declaration of rights for women. This declaration became Olympe de Gouges’ most famous work, the Declaration of the Rights of Woman and the Citizen, or Déclaration des droits de la femme et de la citoyenne, which was published around September of 1791 as a response to the Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen. The Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen was published in 1789 as the official declaration of the French Revolution. Olympe’s declaration expanded on the rights decreed by the 1789 declaration but focused exclusively on the inclusion and equality of women into the public sphere of French society. In order to prevent any misunderstanding, Olympe de Gouges utilized the same language and grammar as the Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen while simply changing “man” to “woman.” Additionally, Olympe dedicated the work to Marie Antoinette in the hope that the queen would support the fight for women’s rights.

However, Olympe de Gouges gained many enemies because of her outspoken nature and her belief that women should automatically receive the same new-found rights as gained by the male citizens. Another reason enemies targeted Olympe de Gouges was due to her continued support of King Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette, even with their trial and execution on charges of treason. Her support and defense of King Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette placed her at odds with Maximilien Robespierre, the leader of the revolutionaries who later became known as the Committee of Public Safety. She harshly criticized Robespierre and advocated for women’s rights in her pamphlet Pronostic de Monsieur Robespierre pour an animal amphibie.9

Her written works and belief that she had the right to speak out on behalf of the citizens of France and argue for the rights of women violated the traditional social boundaries that even the revolutionaries upheld. Subsequently, on July 25, 1793, Olympe de Gouges was charged with sedition for having written works against the wants and needs of the nation of France and directly opposed those in power. She was immediately imprisoned, and a public prosecutor began reviewing her writings before her interrogation began on August 6, 1793. The public prosecutor determined Olympe had written works that were an attack on the sovereignty of the people, that she had questioned and provoked civil war, and sought to arm citizens against each other. The trial was brief and one-sided because the prosecutor refused to provide a defense attorney for Olympe de Gouges, stating that she claimed to be more than capable of defending herself as she had written herself to be her own defense in her writings.10 Olympe de Gouges was found guilty, condemned to death, and executed by guillotine on November 3, 1793.

- Holly Grout, “Exceptional Women: Rights, Liberty, and Deviance in the French Revolution,” Feminist Collections: A Quarterly of Women’s Studies Resources 30, no. 3 (June 22, 2009): 6. ↵

- Marie Maclean, “Chapter 5: Opposition and Revolution: Olympe de Gouges and the Rights of the Dispossessed,” in Name of the Mother (Taylor & Francis Ltd / Books, 1994), 89-90. ↵

- Marie Maclean, “Chapter 5: Opposition and Revolution: Olympe de Gouges and the Rights of the Dispossessed,” in Name of the Mother (Taylor & Francis Ltd / Books, 1994), 91. ↵

- “Translating Slavery, Volume 1 : Gender and Race in French Abolitionist Writing, 1780-1830,” accessed February 26, 2021. ↵

- “Estates-General,” Funk & Wagnalls New World Encyclopedia, January 1, 2018, 1. ↵

- “Estates-General,” Funk & Wagnalls New World Encyclopedia, January 1, 2018, 1. ↵

- “1789-1791: The Revolution | Archives & Special Collections,” accessed March 10, 2021. ↵

- Elizabeth Racz, “The Women’s Rights Movement in the French Revolution,” Science & Society 16, no. 2 (1952): 159. ↵

- Marie Josephine Diamond, “The Revolutionary Rhetoric of Olympe de Gouges,” Feminist Issues 14, no. 1 (Spring 1994): 10. ↵

- Holly Grout, “Exceptional Women: Rights, Liberty, and Deviance in the French Revolution,” Feminist Collections: A Quarterly of Women’s Studies Resources 30, no. 3 (June 22, 2009): 6. ↵

16 comments

Karla Fabian

Before reading this article, I did not know anything about Olympe de Gouges. It was very intriguing to read that Gouges based each of her writings on a social issue, which in my opinion was very extraordinary within this era, as women, in general, underwent a lot of gender inequality. As stated in the article, some of Gouges’ plays were accepted until she unveiled her gender. Also, it is very inspiring to see how Gouges worked and fought for gender equality, as it states that she was involved in political works, where she discussed social reforms intending to support women’s rights within the revolution. This also shows how Olympe was out of the ordinary stereotypical women in this era, as she fought for women to work, to have a better education, and a possibility for women to be better recognized in the theater world. It is very empowering to see how Olympe, even though in an era when women did not have much voice, fought until her death to change that, it shows her determination for an equal gender opportunity world.

Haley Ticas

HI Madeline! This was a great well written article. I commend you for choosing a woman as i always enjoy reading about strong and inspiring females. I had never heard of Olympe, however i am glad to have come across and have read this article. Her story of fighting for equal rights and what resulted from it was greatly detailed and interesting to read. Great job!

Allison Grijalva

Hi Madeline! I had never heard of Olympe de Gouges but it was so refreshing to learn about her strength and character! It is not often at all that we are able to read about women highlighted for their strength and power during this time in history, as they were mainly considered to be background characters and second hand citizens. This was like I said a refreshing read.

Grace Frey

I always love learning about learning about powerful women in history and this article was no exception! The author did a great job detailing her story and her struggle for equality. While it is tragic that her fight led to her death, she joined the many women who died for their campaign for equal rights and treatment. While it is somewhat surprising to me that I had not heard of her up until now, it may have something to do to with country’s different focus on different important figures, depending on whether they came from their country or not.

Valeria Varela

The article was very well written and it describes the story of Marie-Olympe de Gouges in a way that had my complete attention. She was a very strong and outspoken women and was beautiful to read about her political works !

Julia Aleman

I really enjoyed reading this informative and interesting article. The title and the beginning really brought my attention and kept me reading for more. Olympe sounds like a really strong woman which was not the most common thing to see around this time period. I love reading stories on woman fighting the gender norms of society and demanding equality in which women should have been guaranteed from the start.

Camila Garcia

The author did a really good job in writing this article. This article highlights how strong a woman can be and shows the reader that Olympe de Gouges was a truly inspiring woman. The detail in the first paragraph is outstanding. The article was really easy to follow and the images added really helped support the text. The letter she wrote really stresses how amazing she was.

Faith Chapman

It never fails to baffle me when a country declares their independence and the rights of all their citizens…except the women. It’s even more baffling since the French constitution, the Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen, included the rights of colored men from the get-go; if it was apparent to include the rights of colored men, an already progressive thing at the time, it shouldn’t have been a problem to include the rights of women too when the women make up the other half of France.

Bonnie Viviano

I too have never heard of Olympe. What a strong and determined women for the mid 1700’s.

Your writing made me feel as though I was right there at the time….could hear the lock turning, and see her walking through the town square to meet her fate. You set the scene and really drew my interest into the story. Very well written!!!

Nathan Pipes

Your history of Olympe reminds me of Voltaire’s maxim on power and authority: “It is dangerous to be right in matters on which the established authorities are wrong.”