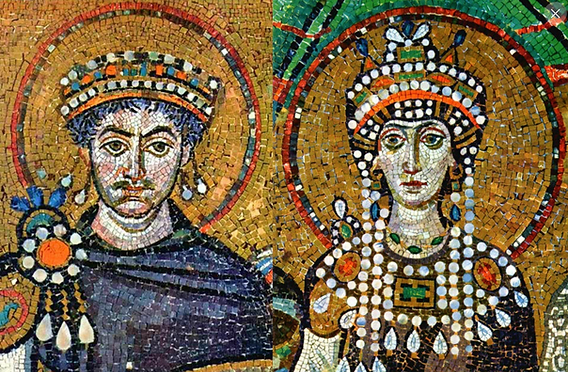

It was the year 532 CE in the great city of Constantinople, part of the Byzantine Empire, home to Emperor Justinian and Empress Theodora. You will find that Constantinople, on a regular day, would’ve received their visitors with a warm welcome and a display of arts and history in every corner, but not today… not for the past week. Unleashed by the rebellion, chaos had overflowed the city and disrupted the line of order that the Emperor and Empress had established. The “Blues” and “Greens,” –similar to political parties nowadays– had come together, for the first time in history, to fight for the same cause: to end Justinian’s and Theodora’s reign. The rioters had made the city their stage and started to set every building they came across on fire, chanting the word “Nika” –which means victory– as they went. This had been going on for a total of six days. On the seventh day, however, Emperor Justinian had come to, what he thought to be, a resolution to his crisis and sought to share it with his council.1

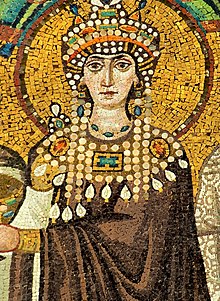

Just outside the palace, the rioters seemed to be getting closer by the minute. The city had been almost totally destroyed by the rebellion and the great Constantinople seemed almost unrecognizable. The clock ticks as Empress Theodora sits beside Emperor Justinian while the last council meeting is being held. After a long back and forth between the council members and the Emperor, the tension in the air is almost palpable, a decision needs to be made. Empress Theodora waits her turn to speak. As the only woman present in the room, she will be the last person to give her opinion on the matter at hand. With Emperor Justinian wanting to flee the city and live at sea with the last of his resources, it seems that the rioters have succeeded and all hope for the current monarchy has been lost. One by one, the council members have vocalized their support for Justinian’s immediate decision and have declared this as the only reasonable course of action to take given his current situation. The empress, however, disagreed with this argument. It seemed like all was lost, the city of Constantinople would be taken by its own people and another person would be named as their king and emperor.2

The “Nika” riot took place in the city of Constantinople. The rebellion was led by their own people, the “Greens” and “Blues.” Both groups represented different ideologies and religions. The reason why? They couldn’t see eye-to-eye. However, in the year 532 CE, both parties decided to leave their differences aside, and they came together to form a union. All of these events, with the purpose of dethroning the current Emperor Justinian, because they disagreed with his policies and the way he had handled previous rebellious attempts by various members of the Greens and Blues. This last party felt especially offended that the emperor had treated their members as if they were criminals and therefore sentenced to death by execution. The more specific reason would be that the execution of two rioters, –one Green, one Blue– ordered by Justinian, had gone wrong. Initially, the method used to execute them was that of hanging, which would be displayed in the Hippodrome; to say that it did not go as planned would be putting it nicely. Instead of being executed, both of the rioters fell to the ground half-alive, half-dead, and therefore brought to the chapel to seek asylum. This is how the riot started and lasted for a whole week before being brought to an end by no other than our beloved Empress Theodora and her glorious plan.3

As previously mentioned, Theodora waited her turn to speak. The room went silent as every last one of the council members said their piece. Nobody seemed to have another solution, plan, or even another idea as to what had to be done to survive, escape, or stop the rebellion. Justinian had made up his mind and had decided to escape Constantinople and board a ship and continue the rest of his life at sea, or until he found somewhere safe to stay for refugee. However, there was a feeling in the room that could have been identified as hope or mere illusion. Everyone seemed to be waiting for a miracle, a saving grace, someone to put an end to their dilemma and free them from all suffering. This was the moment when Empress Theodora rose from her seat, catching everybody’s attention. It was finally her turn to speak her mind and say what she had been thinking and orchestrating the entire time everybody had been so busy agreeing to surrender. She delivered a speech with such grace leaving everybody mesmerized by her words and show of courage. From the council members to her husband, Emperor Justinian, she had left them all astonished and somehow hopeful at her words. She sought fighting before fleeing. War over surrender.4

Theodora addressed the assembled men: ”

As for the belief that a woman ought not show daring in the presence of men, or act boldly when men hesitate, in the present crisis, I think, we have no time left to ask if we accept it or not. For when what we hold is in extreme peril, we are left with no course of action except to make the best plan we can to deal with the plight we face. As for me, I believe that flight is not the correct course to take now, if ever, even if it serves to save our lives. For no person who has been born can escape death, but for a man who has once been emperor to become a runaway that we cannot bear! I hope I never have the imperial purple stripped from me nor live to the day when the people I meet fail to address me as empress! So if what you want is to save yourself, O Emperor, it’s no problem. We have plenty of money; over yonder is the sea, and here are the boats. Yet ask yourself if the time will come, once you are safe, when you would gladly give up security for death. As for me, there is an ancient maxim I hold true, that says kingship makes a good burial shroud.5

Theodora preferred to become captive or even die at the rioters’ hands rather than show weakness by fleeing the city and becoming a martyr. She would rather fall with the city than take the easy way out and hide because, from her perspective, that’s what an Empress does. Taking the role of an empress didn’t just mean embracing the good parts, but also the hard choices and battles.6 She delivered all of these opinions and ideas during her speech and left the council members wondering if she had a plan. Her answer to the question was yes, she did indeed have a plan.7

First, they would send a messenger into the city with a bag full of gold. With the gold, they would attempt to bribe the Blues, reminding them that the Emperor was still a Blue and therefore, they should support him. They would use this as a distraction to set the stage for where the actual plan would unfold. They would use the Hippodrome as it was an enclosed place, with only two entrances, already filled with rioters. Then, they would send two soldiers to quietly close both gates and guard them. They would use the rest of their soldiers to infiltrate the Hippodrome using the Emperor’s box, which had a door connected directly to the palace. This would give them the element of surprise, which would give them some advantage when fighting against the rioters. A massacre was about to happen.8

After Theodora’s explanation, everybody rushed to put the plan into action. Emperor Justinian started by ordering two of their soldiers to guard the two entrances to the Hippodrome. The soldiers then moved into the Hippodrome through the Emperor’s box. Taking the rioters by surprise, they attacked. Without a way of escape, the rioters were forced to fight the soldiers. Due to the surprise of the attack, none of the people previously present in the Hippodrome were prepared to fight such strong forces as the attackers. Approximately 3,000 corpses were dragged out of the Hippodrome the next morning. Not only did this act put an end to the riot but it also solidified the Empresses’ power as a true ruler, a true monarch.9

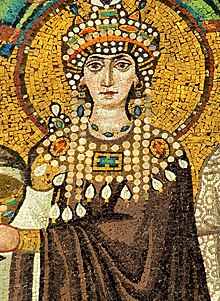

After the massacre was over, it took time for the rest of the people of Constantinople to go back to normal. Only a few stores dared to open and people were still hiding in their houses even after a week had passed since the riot was brought to an end. Justinian and Theodora started the plans to reconstruct the city even better than it was before the riot. They started by planning the rebuilding of the Hagia Sophia, which still stands to this day, reminding everybody who Empress Theodora was and what she had done for the city. By showing the courage that all of the council members and the Emperor lacked, Empress Theodora became an even stronger political figure than she was before. Now, not only was she looked at as Emperor Justinian’s equal but she was also respected as a strong female figure in history.10

- W. T. Townsend, “Theodora : From Stage to Throne,” Dalhousie University Libraries, Public Affairs: A Maritime Quarterly for Discussion of Public Affairs 14, no.03 (1952): 37-38, https://hdl.handle.net/10222/75983 ↵

- W. T. Townsend, “Theodora : From Stage to Throne,” Dalhousie University Libraries, Public Affairs: A Maritime Quarterly for Discussion of Public Affairs 14, no.03 (1952): 37-38, https://hdl.handle.net/10222/75983. ↵

- J.A.S. Evans, “The Empress Theodora: Partner of Justinian,” Choice Reviews Online 40, no. 07 (March 1, 2003): 40-4155, 25-47, https://doi.org/10.5860/choice.40-4155. ↵

- Evans, J. A. S. “THE ‘NIKA’ REBELLION AND THE EMPRESS THEODORA.” Byzantion 54, no. 1 (1984): 380–82, http://www.jstor.org/stable/44170874. ↵

- J.A.S. Evans, “The Empress Theodora: Partner of Justinian,” Choice Reviews Online 40, no. 07 (March 1, 2003): 40-4155, 25-47, https://doi.org/10.5860/choice.40-4155. ↵

- Evans, J. A. S. “THE ‘NIKA’ REBELLION AND THE EMPRESS THEODORA,” Byzantion 54, no. 1 (1984): 380–82. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44170874. ↵

- W. T. Townsend, “Theodora : From Stage to Throne,” Dalhousie University Libraries, Public Affairs: A Maritime Quarterly for Discussion of Public Affairs 14, no.03 (1952): 38, https://hdl.handle.net/10222/75983 ↵

- W. T. Townsend, “Theodora : From Stage to Throne,” Dalhousie University Libraries, Public Affairs: A Maritime Quarterly for Discussion of Public Affairs 14, no.03 (1952):38, https://hdl.handle.net/10222/75983 ↵

- W. T. Townsend, “Theodora : From Stage to Throne,” Dalhousie University Libraries, Public Affairs: A Maritime Quarterly for Discussion of Public Affairs 14, no.03 (1952):38, https://hdl.handle.net/10222/759 ↵

- Charles Pazdernik, “‘Our Most Pious Consort Given Us by God’: Dissident Reactions to the Partnership of Justinian and Theodora, A.D. 525-548,” Classical Antiquity 13, no. 2 (October 1, 1994): 256–81, https://doi.org/10.2307/25011016. ↵

8 comments

Macarena Machado Combe

The article provided a detailed historical context of the Byzantine Empire during the sixth century, the Nika riots and the political dynamics of the time. Learning about the union of the Blues and Greens against a common enemy was particularly enlightening and interesting, especially with the contrast made at the beginning with political parties nowadays. This article demonstrated that courage goes hand to hand with strategic thinking to face any adversity. Finally, the article was informative and interesting to read.

Byron Marinelarena

Theodora is a powerful historical figure, remembered for her courage and unwavering resolve in a moment of crisis. This is very influential to young women who want to be leaders for their communities and organizations.

Danielle Villanueva

Wow, this story about Empress Theodora is incredible! I was amazed by her courage during the Nika riots and how she refused to run away when everyone else wanted to give up. Her powerful speech to the council showed real leadership, and I loved how she came up with a bold plan to save the city. It’s inspiring to see a woman in ancient times who was so brave and strategic. I wonder what gave her the strength to stand up to the rioters when everyone else was afraid?

Emilio Orona

I really like how your emphasis was on Theodora’s leadership. Leadership is not only correlated to the Marianist characteristics but also in life overall. Very good detail leading to the riots. Very strong visuals and shows how Justinian and Theodora were very important since they were usually portrayed in the ceilings or walls of cathedrals and churches with the color purple. However, I do believe you should’ve research more on Justinian to make the contrast stronger and make Theodora stand out more or just simply for duality reasons.

Alysia Cano

Empress Theodora’s courage and decisive leadership during the Nika riots showcase her remarkable strength and intellect in the face of overwhelming adversity. Her refusal to flee, coupled with her bold strategy, not only saved the Byzantine Empire but also solidified her legacy as a powerful ruler and visionary. The rebuilding of Constantinople particularly the Hagia Sophia, stands as a lasting testament to her resilience and unwavering commitment to her people.

ncuarenta

Empress Theodora’s story is amazing. When everyone else wanted to run away, she stood her ground and reminded them what it means to be a real leader. Her speech was so brave, and her plan to stop the rebellion was smart, even though it was harsh. What really stuck with me was how she didn’t give up, even when things were at their worst. After everything, she helped rebuild the city, including the Hagia Sophia, which is still famous today. She wasn’t just a queen; she was a total boss who saved Constantinople when it needed her the most.

irodriguez43

The level of detail in your essay is incredible! You didn’t just touch on the main points you really dove deep, providing examples and explanations that made the topic so much clearer and more compelling.

Bianca Solimano

Very interesting reading! I enjoyed it. Good job Brianna! C: