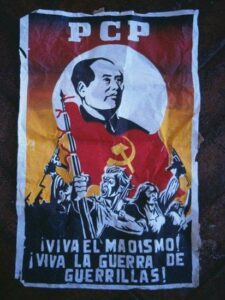

Throughout history there have been a great number of socio-political movements with the goal of taking down the oppressive systems set in place by the ones in power. With every revolutionary movement, there is a political ideology that follows. The Cold War Era created a debate on which governing system should be the new world standard, democracy or communism. Many newly decolonized countries were forced to pick a side. For many Latin American countries, communism was seen as a solution to the oppression felt under previous systems. There was an establishment of communist parties, and, in Peru, the communist party Sendero Luminoso, otherwise known as the Shining Path, would become one of the world’s most persistent and violent insurgent group. This group was created by the philosophy professor Abimael Guzman in the 1970s, who utilized the developing ideologies of Marxism, Leninism, and Maoism to accomplish the overthrow of the Peruvian government and the construction of a communist peasant regime.1

During the beginning of the 1950s, the Peoples Republic of China and the Soviet Union were the main communist states in the world. In a sense, they ironically competed to see which version of Communism should reign supreme. In attempts to preserve the Chinese version of communism, Mao Zedong, Chairman of the Chinese Communist Party, initiated the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution in the late 1950s. In 1959, China invited communist leaders from different regions of the world, such as Latin America, expecting to teach Latin American communists the way of Chinese communism. Abimael Guzman was one of the many communist individuals who attended these revolutionary training classes.2

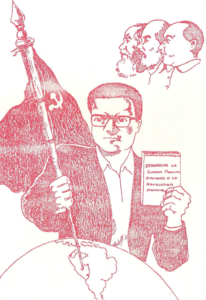

Guzman traveled twice to China, with his first trip being in 1965.3 During this visit, Guzman attended a cadre school in Beijing where he received political training. The concept of a cadre school is derived from Leninism. At these schools, individuals are taught the important aspects of an insurrection. In Beijing, Guzman took eight courses on the experience of the Chinese Revolution. He studied the international situation, general political line, peasant work, principal force of the revolution, party building, mass line, secret work and own work, and philosophy. These eight courses covered questions about the works of Mao and other Chinese leaders pertaining to the united front, the armed struggle, and Maoist philosophical thought.4

Guzman continued his cadre training courses in the city of Nanjing. There, Guzman also received military training. He learned lessons on how to organize a revolution and how to build an army. He also studied strategy and tactics, forms of combat, as well as bomb-making techniques and other guerrilla warfare tactics. It was important for those attending these training courses to keep the Maoist theory of a “peoples war” in mind. “Peoples war” refers to a revolution beginning with the proletariat. Mobilizing from poor areas to big cities, taking over town by town until they finally take over the capital. Teachers at the cadre school would use the Maoist theory as a form of motivation to ensure that the trainees were able to do everything they were taught and able to do it correctly for that matter.5

During his stay, Guzman traveled around the country and witnessed historic sites as well as the progress of socialist construction in action at Shanghai, Guangzhou, Xi’an, and Yan’an. This made him understand and feel more connected to the Maoist ideology. Later, he recalled the “tireless, massive, heroic struggle of the socialist construction. Building the new society, socialism, laying the foundations for future communism.”6

Details on Guzman’s second trip to China are a bit hazy. Guzman gave contradictory dates for his second trip, but the most likely period would probably be a month or two between November 1966 and November 1967.7 Guzman traveled to China as the representative of PCP-Bandera Roja, a fraternal party of the CCP- The Chinese Communist Party. Here he engaged in comradely and confidential exchanges with high level Chinese communists regarding the cut of monetary funds from the CCP to the PCP.8

The most important aspect of his second trip was his in-depth exposure to the CR, Cultural Revolution, with his first direct contact being when he got to meet the Shanghai revolutionary committee. Shanghai was known as the political epicenter of the CR. The high level of mass mobilization during the CR had a major impact on him. He went so far as to say, “in 65, marches were conventual, silent; 67 was thunderous.”9 Guzman said that China had transformed for the better. In Beijing, there were marches and developments of socialism. Guzman learned a lot about the Cultural Revolution through the Red Guard with whom he lived. The Red Guards were a group of militant university and high school students formed into an unofficial military force. For young people, the Red Guard movement offered a sense of political progress in China.

Guzman argued that only a complete revolutionary reconstructing could “redeem” Peru. As previously stated, Guzman was a dedicated follower of Chairman Mao Zedong. But not only did Guzman gain inspiration from Mao, but also from Jose Carlos Mariategui, a Peruvian Marxist. Mariategui used Marxism to explain Indigenismo, a minority leftist thought that centers around the belief that Indigenous people are being oppressed by capitalist institutions both socially and economically and that they must be included in society.10 Even after decolonization, the classist systems that were previously installed left a mark in Peruvian society and continued this oppression. Abimael Guzman wanted to see how the peasants’ lives were experienced in Ayacucho. He stated that it was worse than he imagined. He mentioned that the farmers and servants had to produce products for big corporations and had none left for themselves.11

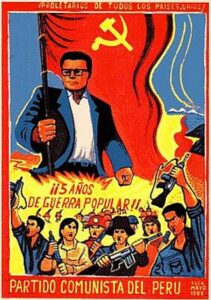

Guzman applied Maoist thought when creating Sendero Luminoso. His revolution required peasant mobilization and would center around the knowledge he obtained at the cadre school. “Manuals of Marxism” were embedded into the school’s curriculum in the 1970s. 12 These would make it possible for students to accept the party’s militaristic style. Many of the people Guzman recruited were poor Indian peasants, and high school and university students from Universidad Actional de San Cristobal de Huamanga. Because he was appointed as personnel director of the university in 1971, he was able to hire more radical faculty who aided him in recruiting students. He won over many students and peasants by promising action and radical change. This proved to be correct when he led a national liberation army at the university to support the poor peasants that were being exploited. Guzman was said to have developed a “cult of personality.” He even earned the nickname of Dr. Shampu because he would ‘brainwash’ listeners. He was a well-educated, well-spoken man that simply by talking, one would accept his views and follow his orders without doubt. Many students were eager to join Sendero Luminoso and act on their experience with poverty and racism. His followers truly saw the Shining Path as an indigenous uprising.13

Guzman, with his “cult of personality,” manipulated and influenced many people to aid this cause and follow it blindly. Many gave Guzman their devotion and support. The Guzman thought emphasized the primacy of class struggle, combating imperialism, the importance of a people’s war and mass struggle, and that violence is a universal law.14 It was believed that without the peasantry and revolutionary violence, the old order could not be overthrown to create a new one. He would later be able to create a well-disciplined, brutal, and hierarchal guerilla movement that would reign in terror for twenty years.

- Eliab S. Erulkar, “The Shining Path Paradox,” Harvard International Review 12, no. 2 (1990): 43–45. ↵

- Joseph J. Lee, “Communist China’s Latin American Policy,” Asian Survey 4, no. 11 (1964): 1125. ↵

- Matthew Rothwell, “Gonzalo in the Middle Kingdom: What Abimael Guzmán Tells Us in His Three Discussions of His Two Trips to China,” TRANSMODERNITY: Journal of Peripheral Cultural Production of the Luso-Hispanic World 9, no. 3 (2020): 117. ↵

- Matthew Rothwell, “Gonzalo in the Middle Kingdom: What Abimael Guzmán Tells Us in His Three Discussions of His Two Trips to China,” TRANSMODERNITY: Journal of Peripheral Cultural Production of the Luso-Hispanic World 9, no. 3 (2020): 117-118. ↵

- Matthew Rothwell, “Gonzalo in the Middle Kingdom: What Abimael Guzmán Tells Us in His Three Discussions of His Two Trips to China,” TRANSMODERNITY: Journal of Peripheral Cultural Production of the Luso-Hispanic World 9, no. 3 (2020): 122-123. ↵

- Matthew Rothwell, “Gonzalo in the Middle Kingdom: What Abimael Guzmán Tells Us in His Three Discussions of His Two Trips to China,” TRANSMODERNITY: Journal of Peripheral Cultural Production of the Luso-Hispanic World 9, no. 3 (2020): 124-125. ↵

- Matthew Rothwell, “Gonzalo in the Middle Kingdom: What Abimael Guzmán Tells Us in His Three Discussions of His Two Trips to China,” TRANSMODERNITY: Journal of Peripheral Cultural Production of the Luso-Hispanic World 9, no. 3 (2020): 127. ↵

- Matthew Rothwell, “Gonzalo in the Middle Kingdom: What Abimael Guzmán Tells Us in His Three Discussions of His Two Trips to China,” TRANSMODERNITY: Journal of Peripheral Cultural Production of the Luso-Hispanic World 9, no. 3 (2020): 127-128. ↵

- Matthew Rothwell, “Gonzalo in the Middle Kingdom: What Abimael Guzmán Tells Us in His Three Discussions of His Two Trips to China,” TRANSMODERNITY: Journal of Peripheral Cultural Production of the Luso-Hispanic World 9, no. 3 (2020): 132. ↵

- Matthew Galway, “Permanent Revolution,” in Afterlives of Chinese Communism, ed. Christian Sorace, Ivan Franceschini, and Nicholas Loubere, Political Concepts from Mao to Xi (ANU Press, 2019), 186. ↵

- Abimael Guzman, “‘Exclusive’ Comments by Abimael Guzman,” World Affairs 156, no. 1 (1993): 54. ↵

- Paul Navarro, “A Maoist Counterpoint: Peruvian Maoism Beyond Sendero Luminoso,” Latin American Perspectives 37, no. 1 (2010): 167. ↵

- Thomas Harvey, “Sendero Luminoso: The Rise of a Revolutionary Movement,” The Fletcher Forum of World Affairs 16, no. 2 (1992): 173-174. ↵

- Eliab S. Erulkar, “The Shining Path Paradox,” Harvard International Review 12, no. 2 (1990): 45. ↵

2 comments

Andrew Ponce

Hello Noelia! This is such a neatly drafted article with great substance and a great overall topic. The coverage of Abimael Guzman is something that I had previously never thought I would find interesting in myself. This man played such a vital role in his community, with her perspectives and interest in the Chinese socialist party. This man contributed different perspectives, leadership styles, and learning techniques of his own. Very important for people to know about and students are lucky this article covers this character.

Gaitan Martinez

Abimael Guzman was a man who saw the bigger picture, learned everything about the Chinese socialist party to further understand the reasoning behind it. When people are unhappy and seek to improve things, and you add a very charismatic man, it’s no wonder how Guzman was able to win over so many people. This article really put a whole new perspective on governments and any type of leadership