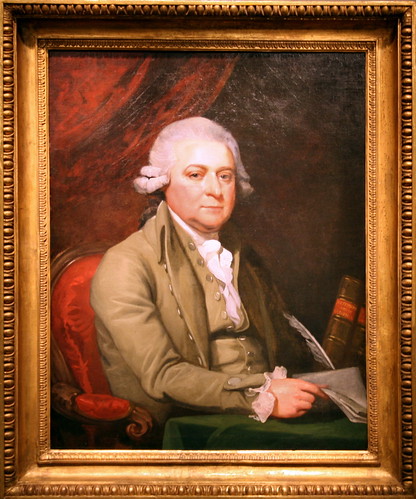

In 1770, John Adams was caught in a deep and internal battle that set him off on a journey that would test his convictions. His deeply rooted commitment to justice conflicted with his strong support of the American independence movement and the well-being of his family. His journey’s starting point was a moral and professional dilemma, which happens to be the central focus of this story. Adams had to make a difficult choice: either come forward and stand alongside the British troops who were charged with the massacre that took place in Boston, or not. His decision sets the tone for a journey of bravery, morality, and justice.

A violent outbreak of fighting broke out in revolutionary Boston in 1770, turning Boston into a battlefield. As a major disaster was developing and destroying the city, tensions between colonists and British troops were at a breaking point. A man who became one of the nation’s strongest leaders found himself in the middle of the deep hatred and growing conflicts in the city. John Adams was not your average attorney; he was highly respected and was always defending the rule of law and justice. He had a reputation for fighting legal battles with the idea that all individuals deserve a fair trial no matter their actions.1 Adams’s faith in the values of justice and legal order remained strong despite the public’s desire for a revolution. He looked behind the obvious and recognized what real justice meant. Adams, not being the typical lawyer, stood firm alongside his dedication to justice, which would force him to face an extremely difficult challenge.2

There had been high levels of tension and chaos in the Boston streets on the evening of March 5, 1770, setting the stage for a massacre that evening, a brutal bloodbath that would go down in the nation’s history. Enraged colonists came together to speak out against the presence of the British army in the city. As things soon got out of hand, Captain Thomas Preston and his seven men appeared on King Street, and the Boston Massacre began. Who fired the first shot and why the soldiers were shooting into a crowd of civilians is still unknown. All that is known is that several citizens were wounded and killed, causing an enormous amount of anger to take over the city. As the Boston people cried for justice, the massacre put the early nation’s legal system and principles to the test.3

John Adams, a man known for his commitment to justice, found himself at the center of this public tension. His journey into this moral and professional dilemma began with an unexpected request from a strange source. James Forrest, a Boston merchant, visited Adams in his house following the events of the Boston Massacre. Forrest was a known companion of the British troops who often shared drinks with British captains. Claiming that no one else was interested in the case, he begged Adams to stand up for the British troops in the upcoming trial. Judge Robert Auchmuty of the Admiralty Court had declined to take part in the case but indicated he would stand by the soldiers if Adams was the one representing the charged men. Additionally, the three Crown attorneys declined to take up the men’s defense. Josiah Quincy, an attorney in Boston and the main voice for the group Sons of Liberty, was another person Forrest visited. Quincy promised that if Adams came forward, he would be willing to defend the British troops as well. Thus, if Adams had not paved the way, no defense attorney would have been able to withstand the anger of the Boston public.4 Captain Preston’s request, through James Forrest, not only shaped Adam’s destiny but took him into the middle of an unprecedented moral and professional dilemma. The city of Boston saw the beginning of a legal and moral exhibition unlike any other in history, with John Adams at the center.

Adams found himself at a crossroads, between the shouts for vengeance and his committed belief in justice. A decision with great implications lay before him. The stakes were high, and Adams was aware of the consequences it might have on his personal life, especially his family. As he contemplated his decision, he knew that by defending the British soldiers, he was potentially risking the safety and well-being of his family. Sadly, the Adams family was mourning the passing of one of the children, and this decision would add to their already high level of stress. The passing had a significant impact on John’s wife Abigail, who became very sick and depressed. Abigail grew more ill, and she was often motionless and, at times, did not communicate with Adams. The possibility of taking the case and adding more stress to Abigail made this choice more difficult.5 On a professional level, this choice was a defining moment in Adams’s legal career. With profound risks, Adam’s reputation for continuous success as a lawyer was at stake. When Adams moved his home from Braintree to Boston, he was already a renowned attorney. Although taking this case would benefit his career if he succeeded in defending the soldiers, it would also testify to his unwavering commitment to the rule of law. However, if he failed, it would hurt his career ruining his reputation as a patriot.6 Adams’s decision was not just a matter of right and wrong; it was a choice that would define the course of his life and career.

An association that significantly contributed to the public’s increasing hatred of the British in Boston was the Sons of Liberty. Therefore, the impact of the Sons of Liberty’s perception of Adam was a crucial aspect that put additional stress on his decision-making. This organization initiated several protest movements and acts of resistance, which included various prominent figures such as Paul Revere, Alexander Hamilton, and Samuel Adams. John Adams had ties to the group and even took part in some of their meetings. Thus, if Adams decided to represent the British soldiers legally, he risked creating a bad image with this passionate group and separating himself from it. The Sons of Liberty would interpret this decision as a betrayal of the revolutionary cause. Adams was conflicted between his commitment to justice and his belief in the independence movement.7 The moral conflict between the safety of his family, the revolutionary movement, and his firm belief in legal principles made this decision very difficult for Adams. The Sons of Liberty’s influence over the Boston people increased the difficulty of the decision, making the potential choice of defending the British troops a brave act of moral courage.

Despite Boston’s rage and demands for retribution, Adams remained faithful in his unwavering belief in the principles of justice. He made the crucial choice to represent Captain Preston and his troops who were being detained as criminals. Despite the pressure from the angry mob gathered outside his home as he talked to Forrest, Adams emerged to announce his decision to the crowd. Adams took the case because he believed the law would overrule the emotions of the cause.8 However, his choice was not met with joyous cheers. He faced backlash from his fellow patriots, who called his decision a betrayal of the revolutionary cause. The decision brought conflict with those who judged his actions as an insult to the very spirit of the movement toward independence.9 Adams, a man of strong principles, was now in the midst of a growing intense storm of public opinion. His fellow patriots looked down upon his commitment to justice. The backlash began to grow, but Adams stood firm in his pursuit of a fair trial.

Word of Adams’s decision quickly spread. He suffered humiliation and taunts from the people. Some even went as far as tossing rocks through his home’s windows and throwing mud at him whenever he walked through the streets. Adams was interrogated and confronted by Sons of Liberty members as he was traveling home, asking if he was standing up for the murderers. In response, Adams explained he was working on the trial since the men were innocent unless proven otherwise. Due to the complexity of the case, Adams could not handle it alone. He invited Josiah Quincy to help him in this challenging battle. Admiralty Court Judge Robert Auchmuty Jr., who had initially declined to be present in the case unless Adams paved the way, now decided to aid Adams and Quincy.10 As public outcry intensified, Adams and his team remained firm in their belief in the pursuit of justice.

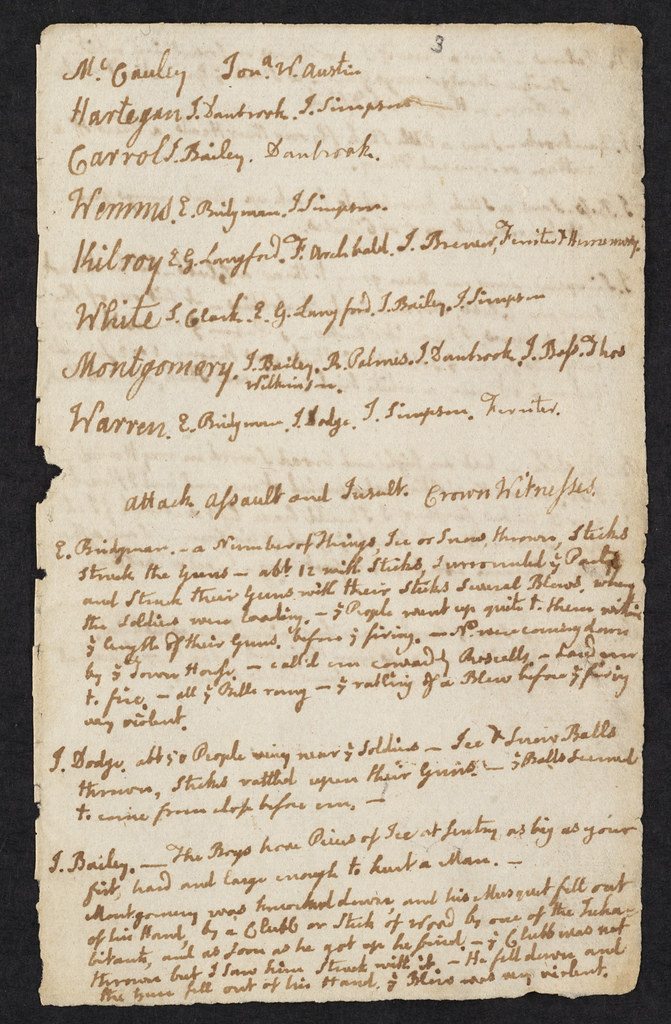

The political environment in Boston was far from favorable towards the accused British soldiers; Adams believed a fair trial would not be allowed. A delay must occur to ensure a fair trial proceeding; if not, the public atmosphere would sway the decision of the court. No judge or jury would give a fair verdict in those circumstances. The case was postponed until June 1770 by Suffolk County Superior Court Chief Justice Lynde, who cited the illness and injury that had kept two of the court’s justices away. However, as June arrived, further delays occurred as the members continued to recover. Judge Lynde thought that all four justices had to be present for a major trial.11 Adams benefited from the delays, but there was also a sense of urgency because Preston and his men wanted the hearing to take place before winter arrived, considering they did not know whether they would be able to travel to England to get the King’s pardon. As it became clearer that time was running out, the issue of dividing Captain Preston’s case from the other British troop’s trial came up. To show that they were all accountable for their actions, the soldiers requested a joint trial; however, on October 24, the Superior Court decided to conduct two different trials.12 As the trial began, tensions in Boston continued to rise, setting the stage for a legal battle that challenged Adams’s principles of justice.

The pressure on Adams and his legal team intensified as the courtroom transformed into a battlefield, impacting Boston’s citizens. Adams’s defense of the soldiers was based on the argument that freemen possess the freedom to defend themselves. Adams realized that explaining to the jury the difference between murder and killing was crucial for the British troop’s protection. He proved that it was unattainable to determine the fact that Captain Preston instructed the soldiers to open fire during the chaos of the Boston Massacre. Adams continued with the argument that free civilians were able to protect themselves to death in an attack and that they had the right to protect themselves against harm. This was a fundamental freedom that applied to both soldiers and free citizens.13 Since the general sentiment was that soldiers were not able to shoot citizens unless they were at war, he faced the difficult challenge of eliminating these myths and proving that a freeman has the privilege to defend himself against an attacker. No matter the circumstances of the war, all freemen were blessed with this right.14 As the pressure mounted and personal doubts and external threats continued to unfold, a battle between the principles of justice and vengeance continued.

The tension in the courtroom was filled with anticipation as the soldier’s trial progressed. Adams, who relentlessly defended the soldiers, prepared to deliver a compelling argument that would challenge the jury’s perception. Adams saw this case as a serious investigation into the principles of justice and individual freedoms rather than as a chance for political gain. Whether one of the jurors is a radical or a loyalist, he claimed that the jurors should ignore their feelings. In Adams’s final remarks to the jury, he passionately declared:

“Facts are stubborn things and whatever may be our wishes, our inclinations, or the dictates of our passions, they cannot alter the state of facts and evidence… The law, in all vicissitudes of government, fluctuations of the passions, or flights of enthusiasm, will preserve a steady undeviating course; it will not bend to the uncertain wishes, imaginations, and wanton tempers of men.”15

His powerful speech on the principles of justice resonated in the courtroom. The courtroom was left in suspense as the justices spoke about the case for a little over three hours the next day to address legalities and procedures.16

The courtroom was filled with tension as the jury prepared to deliver its verdict. Captain Preston and his troop’s lives were in jeopardy. The justices were forced to dismiss the jury from continuing to deliberate at 1:30 pm and requested that they return at 4:00 pm after John Adams’ passionate speech weakened the prosecution’s case. Everyone in the courtroom was waiting anxiously for the verdict to be revealed, and when it finally did, it sent shockwaves through the room and throughout the city of Boston. Just Montgomery and Kilroy, two members of the British troops, were convicted and found guilty of manslaughter. In contrast, Captain Preston and the rest of the troops were found “not guilty” of murder charges. The result was remarkable, securing Adams’s strong confidence in the power of justice and the authority of the law even in moments of revolution.17 There was an immediate feeling of disbelief because this result showed the incredible moral courage of Adams, who had bravely stood up to extreme pressure to make sure justice was served, even at the expense of his own family and reputation.

Nonetheless, Boston’s reaction to the decision was divided. A portion of the public felt that justice was truly done, while others saw the jury’s verdict as contrary to the colonial protest movement. Several individuals felt more enraged after the court’s decisions, and as a result, threats were made against Preston and his men. This forced Preston to leave his base of operations at Castle William, where he thanked Auchmuty but neglected to thank Adams and Quincy. Even other patriots continued to debate Adams’ risky decision to defend the soldiers. For some, it was difficult to understand how an advocate for American independence could defend the enemy. Adams was profoundly impacted by the trial on a mental and physical level. He moved back to Braintree following the case to recover. Adams stood up for the troops since it was the correct thing to do, not because he wanted anything from them. The moral strength to defend the freedoms of the British soldiers was crucially needed throughout the trial. As freemen, they were guaranteed protection and a fair trial. That day, March 6, Adams had the option to simply tell Forrest to leave his property and carry on with his usual life, preserving his good standing with the city of Boston and improving his career. Nonetheless, he advocated for the British troops because he recognized that it was the proper thing to do. If Adams turned down Forrest’s request, he could not possibly be capable of living with himself.18 Despite the controversy surrounding Adams’s choice, his commitment to justice is acknowledged as a substantial contribution to the principles that built the foundation of the United States.19 The decision indicated the struggle that would shortly drive the country closer to the verge of revolution and added to the already growing disputes between the thirteen colonies and British rule.

- Eugene Scalia, “John Adams, Legal Representation, and the ‘Cancel Culture’,” Harvard Journal of Law & Public Policy (Harvard Society for Law and Public Policy, Inc., January 1, 2021), 335. ↵

- William Pencak, “The Lawyer, the Judge, the Historian: Shaping the Meaning of the Boston Massacre, American Revolution, and Popular Opinion from 1770 to the Present Day,” International Journal for the Semiotics of Law – Revue Internationale de Sémiotique Juridique 22, no. 1 (March 1, 2009): 72. ↵

- John Adams: The President Who Defended the Redcoats, Untold, accessed November 5, 2023, https://untoldhistory.org/john-adams-the-president-who-defended-the-redcoats/. ↵

- Kenneth A. Turner and Tanasha N. Stinson, “Certain Principles Are Eternal: The Boston Massacre Trial and the Moral Courage of John Adams,” Army Lawyer 2021, no. 4 (January 1, 2021): 74–82. ↵

- Kenneth A. Turner and Tanasha N. Stinson, “Certain Principles Are Eternal: The Boston Massacre Trial and the Moral Courage of John Adams,” Army Lawyer 2021, no. 4 (January 1, 2021): 74–82. ↵

- Margaret H. Marshall, “John Adams: Lawyer, Absentee Chief Justice, and Author of the Massachusetts Constitution,” Massachusetts Legal History 10 (January 1, 2004): 38-39. ↵

- Kenneth A. Turner and Tanasha N. Stinson, “Certain Principles Are Eternal: The Boston Massacre Trial and the Moral Courage of John Adams,” Army Lawyer no. 4 (January 1, 2021): 74–82. ↵

- Kenneth A. Turner and Tanasha N. Stinson, “Certain Principles Are Eternal: The Boston Massacre Trial and the Moral Courage of John Adams,” Army Lawyer no. 4 (January 1, 2021): 74–82. ↵

- John Phillip Reid, “A Lawyer Acquitted: John Adams and the Boston Massacre Trials,” The American Journal of Legal History 18, no. 3 (July 1, 1974): 195. ↵

- Kenneth A. Turner and Tanasha N. Stinson, “Certain Principles Are Eternal: The Boston Massacre Trial and the Moral Courage of John Adams,” Army Lawyer no. 4 (January 1, 2021): 74–82. ↵

- Kenneth A. Turner and Tanasha N. Stinson, “Certain Principles Are Eternal: The Boston Massacre Trial and the Moral Courage of John Adams,” Army Lawyer no. 4 (January 1, 2021): 74–82. ↵

- William Pencak, “The Lawyer, the Judge, the Historian: Shaping the Meaning of the Boston Massacre, American Revolution, and Popular Opinion from 1770 to the Present Day,” International Journal for the Semiotics of Law – Revue Internationale de Sémiotique Juridique 22, no. 1 (March 1, 2009): 74. ↵

- Kenneth A. Turner and Tanasha N. Stinson, “Certain Principles Are Eternal: The Boston Massacre Trial and the Moral Courage of John Adams,” Army Lawyer no. 4 (January 1, 2021): 74–82. ↵

- John Phillip Reid, “A Lawyer Acquitted: John Adams and the Boston Massacre Trials,” The American Journal of Legal History 18, no. 3 (July 1, 1974): 192. ↵

- Kenneth A. Turner and Tanasha N. Stinson, “Certain Principles Are Eternal: The Boston Massacre Trial and the Moral Courage of John Adams,” Army Lawyer no. 4 (January 1, 2021): 74–82. ↵

- John Phillip Reid, “A Lawyer Acquitted: John Adams and the Boston Massacre Trials,” The American Journal of Legal History 18, no. 3 (July 1, 1974): 202-203. ↵

- Kenneth A. Turner and Tanasha N. Stinson, “Certain Principles Are Eternal: The Boston Massacre Trial and the Moral Courage of John Adams,” Army Lawyer no. 4 (January 1, 2021): 74–82. ↵

- Kenneth A. Turner and Tanasha N. Stinson, “Certain Principles Are Eternal: The Boston Massacre Trial and the Moral Courage of John Adams,” Army Lawyer 2021, no. 4 (January 1, 2021): 74–82. ↵

- Dan Abrams and David Fisher, “John Adams Defended Enemy Soldiers in Court. 250 Years After the Boston Massacre, Here’s How That Case Is Still Shaping Legal History,” Time Magazine (online), March 6, 2020. ↵

1 comment

Eduardo Saucedo Moreno

Hello Jared, what a great read! John Adams is someone who I have learned a lot about throughout the years. Something that I never came across is an article that did such a good job with writing the story of who John Adams was as well as his accomplishments in American history. I liked the substance of the article since it was engaging from beginning to end. Overall, good job!