Deep within the sprawling Omaha Reservation, where the flat land kisses the boundless sky, resided a young girl named Susan La Flesche. She roamed with freedom under the gentle warmth of the sun, finding solace in the open embrace of the surroundings. In this sacred place, time seemed to stand still. The wind carried ancient tales with its gentle whispers, and dreams stretched out as far as the eye could behold. Here, amidst nature’s embrace, Susan discovered a sense of serenity and inspiration, her spirit dancing as freely as the land that surrounded her.1

This girl adored her tribe deeply. In her formative years within the Omaha community, in addition to embracing the traditions, dialect, festivities, and melodies of the tribe, little Sue witnessed the difficult living circumstances they faced. When she was a young girl, Susan volunteered to assist an ailing and aging woman of her tribe. She stayed with her throughout the night, hoping that a physician who was of European descent would come. Four times they sent someone to bring him, but he never came. In the early hours of the morning, Susan sadly watched as the elderly woman passed away in agony. She later recalled that the woman’s Indian ethnicity was inconsequential and held no significance to the white physicians. The heartbreaking incident made little Sue realize just how much her people needed a good doctor. It deeply influenced her life’s journey, inspiring her to become a beacon of hope and healing for her community.2

In the Native American community, Indian mothers held significant roles as healers. They possessed a deep knowledge of the flora world that surrounded them. Mothers taught their daughters how to use various plants to care for their loved ones. For instance, they would steep the leaves of wild sage in hot water to create a soothing tea. It could help with winter colds and flu. They would make braided sweetgrass ropes and burn them to alleviate asthma symptoms. Boiled yucca plant roots were used as a natural shampoo, while sweet flag roots were known to soothe tummy troubles. Traditional medicine women carried medicine bags filled with remedies for various ailments, including poison ivy, constipation, fevers, chills, toothaches, and even snakebites. Their knowledge and practices were deeply rooted in nature and passed down through generations, providing their communities with gentle and effective healing solutions.3

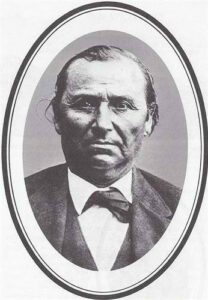

However, Susan’s father had chosen a different path for his youngest daughter, deviating from the traditional ways. He guided her towards a different direction, leading her down a unique and often solitary path, where footprints were scarce.

It is truly impossible to overlook the profound influence of Susan La Flesche’s father, Joseph La Flesche. He held a significant position in shaping her core beliefs and aspirations. Joseph consistently emphasized to his children the immense value of education, a fundamental principle he believed they should embrace from the European civilization. He said that learning was the essential factor in saving their community and attaining prosperity. He also highlighted that education was a means for self-improvement and a way to empower themselves.4

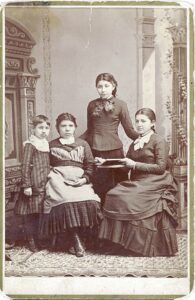

The father sent his youngest daughter to the school affiliated with the Presbyterian Church located on the reservation to learn English. Afterward, she embarked on a journey to Elizabeth School, New Jersey, seeking further education. During moments of fear and uncertainty, as the railcar carried her away from the familiar faces and places she held dear, Susan could recall the words her father had spoken to her years before. She could reflect on that precious memory from her early childhood when she was just six years old. It was a time when her father, Joseph, had gathered her and her sisters, pulling them aside in their village, posing a question that would resonate within her. The father tenderly addressed his daughters and pondered whether they preferred to be referred to as “those Indians” or if they aspired to receive an education and establish their identities in the wider community.5

It is fascinating to recount a remarkable moment when Susan crossed paths with Alice Fletcher, a groundbreaking forty-five-year-old Harvard scholar, who journeyed to the Omaha reservation to delve into the depths of Native American culture and customs. This meeting would leave an indelible mark on Susan’s life. Alice Fletcher carried a burden upon her shoulders – the weight of inflammatory rheumatism that tested her strength and endurance. Bedridden for a challenging stretch of five months, she couldn’t muster her usual energy and determination. Throughout those extended months, a devoted, diligent, and cheerful young girl attended to Fletcher’s needs almost every day. Susan La Flesche, week after week, took care of the scholar from the East Coast. Day after day, she remained by Fletcher’s side, gradually nursing her back to health. During this time, Susan keenly observed the agency doctor’s actions and words whenever he visited his patient. As time passed, Fletcher’s recovery took shape, and she slowly regained her focus on the task at hand.6

Amidst her bustling schedule and tireless efforts, Alice Fletcher’s thoughts frequently drifted towards the eighteen-year-old Omaha girl who had devoted herself to nursing her back to health during the long five months together. In Susan La Flesche, the Harvard anthropologist had witnessed what many others had already recognized: a remarkable intelligence, unwavering focus, disciplined determination, profound maturity, and a kind-hearted spirit.7

Recognizing young Sue’s remarkable abilities and promising future, Fletcher enthusiastically urged her to return to the eastern part of the country and enroll at the prestigious Hampton Institute. Noted as one of America’s oldest and most acclaimed educational institutions for non-white learners, Hampton Institute initially admitted Black pupils and afterward expanded its scope to cover American Indians.8

Due to Susan’s strong English skills, she was placed in the standard curriculum, which required a high level of engagement. Moreover, Susan’s exceptional skills allowed her to take on the additional responsibility of tutoring fellow students who had received less formal education. Her academic journey at Hampton included a diverse range of subjects such as government, history, politics, physics, biology, and the further exploration of English.9

Susan remained unwavering in her purpose throughout her time at Hampton. She held onto the need to excel, channeling all her energy, discipline, and focus to push herself further. The growing number of people who counted on her, including herself, were the kind of people she couldn’t bear to disappoint. From witnessing the indifference of a white doctor towards a sick Indian woman to her father questioning if his daughters wanted to be “simply called those Indians,” to the days spent nursing the Harvard anthropologist back to health, these experiences fueled Susan’s determination. Thoughts of change, growth, and maturity took root within her, steadily shaping her resolve. Now, in the final month of her senior year at Hampton, Susan made an extraordinary decision. She resolved to pursue something no Indian woman had done before: to try to get into medical school, to become a doctor.10

From Hampton Institute, Susan graduated in 1886, accomplishing the program of three years in a remarkable two-year period. She was a salutatory speaker at the graduation ceremony, reflecting on fond memories and offering precious perspectives from her upbringing in her homeland. Susan expressed her awareness of the challenging journey that lay ahead, acknowledging the need for perseverance and faith to achieve success. She expressed gratitude for the opportunity given to her by the Lord and anticipated the future with immense joy and enthusiasm.11

With her sights set on medical school, Susan received a recommendation from Martha Waldron, the resident physician at Hampton. Waldron proposed that Susan attend the College of Medicine in Pennsylvania. During that era, the college was a pioneer in healthcare studies and held the notable distinction of being the top school of medicine in America to open its doors to females. It was an exceptional and fitting choice for Susan.12

Despite graduating from Hampton School with outstanding achievements, including a gold medal, Susan faced an unexpected and disheartening turn of events. The Medical College rejected her scholarship application, leaving her and everyone else astonished. This rejection marked the beginning of a series of hurdles and barriers she would encounter on her journey. Just like today, the financial burden of medical school tuition posed a significant challenge for underrepresented students. However, there was an additional obstacle that Susan had to confront. During those years, the mainstream medical establishment held a low regard for female doctors, often condescendingly referring to them as “doctoring ladies.” Medical colleges exclusively for women and the preparation they provided, considered to be of lesser quality, were often disregarded. Additionally, female physicians faced obstacles in gaining membership in medical societies at various levels, including local, state, and national. They propagated harmful stereotypes, suggesting that if a woman pursued a medical career, she would be incapable of fulfilling her roles as a mother and wife.13

In the late nineteenth century, the prevailing views held by those in power emphasized that women’s primary role in the community centered around marriage, domestic life, motherhood, family, religious involvement, and charitable pursuits. These expectations were particularly emphasized for women belonging to the middle and upper classes, while even women from lower-class and rural backgrounds were encouraged to adhere to these societal norms. These views were not merely theoretical; they were often supported by scientific justifications that could be found in some of the most widely-read scientific journals of that time.14

According to the December 1878 edition of Popular Science Monthly, as society progressed and brain size expanded, it was hypothesized that men, with larger brain volumes than women, must excel in intellectual abilities.15

In an 1864 article in the Journal of the Anthropological Society of London, it was argued that women faced physical and mental challenges during menstruation that hindered their ability to think and act. As a result, there were doubts about considering them fully responsible individuals during this time. The article also claimed that men, not experiencing these disruptions, have historically and will continue to outperform women in intellectual pursuits.16

During the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, women were increasingly regarded as inferior in various aspects of American society. They were denied the right to vote, had limited representation in public and private positions, had limited career opportunities beyond caregiving roles for children, seniors, or ailing individuals. Additionally, their opinions on matters of public significance were often disregarded unless validated by males.17

Despite these discouraging attitudes, Susan’s determination and resilience continued to guide her forward. To overcome financial obstacles, Susan reached out to Alice Fletcher once again, seeking her invaluable support and guidance. With Fletcher’s help, the Connecticut Indian Association came forward to offer assistance. This organization was committed to helping American Indians pursue cultural progress and occupations that were seen as respectable, refined, and in line with the societal norms and expectations of the era.18

To make the dream a reality, the association devised a plan to raise funds. They decided to go public, appealing to ordinary citizens in Connecticut for help in supporting Susan’s education. The association crafted an article about Susan, which they published in a newspaper, capturing the hearts of the community. The response was remarkable, with both private and government funds contributing to Susan’s education.19

After facing numerous challenges, Susan finally received acceptance from the medical college, with the Connecticut Indian Association generously covering her tuition expenses. However, another obstacle awaited her: the cost of the long journey to Philadelphia from her home near the Missouri River in Nebraska. When the Department of the Interior refused to provide train fare, Susan found herself in a state of panic, unsure of how to proceed. But just when all hope seemed lost, the Director of the Connecticut Women’s Indian Association, Sara Thomson Kinney, stepped in. With great kindness and generosity, she reached into her own pocket and sent the much-needed funds.20

At twenty-one years old, Miss Sue embarked on a remarkable journey, leaving behind her familiar surroundings to join the Medical School for Females in Pennsylvania, located nearly 1,300 miles away.21 Susan faced significant challenges in adapting to the learning environment of the medical school. The educational structure and teaching philosophy differed greatly from her previous experiences at Elizabeth School in New Jersey and Hampton School in Virginia. Expressing her struggles to her sister, Susan wrote, “We have no visitations at all – different professors lecture to us. We take notes as fast as we can, then we study up the subject by ourselves. We have to pass 90 percent so of course we want to get all we can get.”22

However, the biggest problem for Susan was that she felt extremely homesick. She was continuously writing long letters to her sisters, telling them all the news she had at college. In each heartfelt message, she couldn’t help but mention the immense struggle of being separated by such a great distance. The longing for the Upstream People, the soothing flow of creeks and rivers, the tranquil woods, and endless plains echoed in her words. Every passing day reminded her of the pain of being far away from her cherished family. “How I wish I was out there with you. Oh! Ro, 3 years from now seems like Paradise when I shall be at home to stay with you all the time…. Tell Mother I am very sorry about her hand. Of course she knows I would gladly give my life for her…. College closes in May, so only 7 mos. left…. I wonder how many times a day I pray for you all…. My dearest Sister-Mother:… don’t you think we ought to feel so very, very rich with each other our dear Father, Mother and each other and our comfortable homes and land.”23

During her time in Hampton, Susan fell in love with a kind-hearted Indian boy named Thomas Ikinicapi, affectionately known as T.I. However, many people around her insisted that he was not a suitable match for her, as his level of education did not align with hers. Yet, Susan remained undeterred by their opinions. She faced constant pressure from various sources, including Miss Folsom, her teacher who disapproved of her friendship with T.I. Additionally, the Connecticut Indian Association, which funded her education, stipulated that she maintain her single status throughout her tenure at medical college and during a period of a few years after finishing the school, so as to dedicate herself fully to her medical practice. She found herself under the watchful eye of the Association, who closely monitored her academic progress. Amidst all of this, Susan also faced pressure from her father, who expressed disappointment that her elder sister was getting married while emphasizing the importance of further education. The weight of these expectations, combined with the impending medical exams, created an unrelenting pressure that Susan could not escape.24 Nevertheless, she remained resolute in her pursuit of her own path.

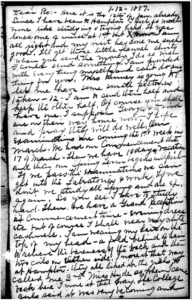

There is a letter written by Susan to her sister Rosalie on January 12, 1887. In this letter, Susan revealed a pivotal decision she had to make: choosing between her education and career or marrying T.I. This letter provides invaluable insight into Dr. Picotte’s character, showcasing her determination to resist the expectations placed upon white women during that time. She made the brave decision to prioritize her college education.25

The medical college offered comprehensive training in a range of medical disciplines, with a specific focus on women’s health, including obstetrics and gynecology. There was a prevailing expectation that female doctors would primarily cater to the healthcare needs of female patients.26 Susan also diligently undertook rigorous courses in fundamental subjects such as organic chemistry, intricate histology, advanced therapeutics, comprehensive anatomy, dynamic physiology, and essential materia medica. As she progressed in her education, she delved into more advanced subjects such as pathology and surgery.27

After completing the initial year of her medical studies, Susan faced financial constraints that prevented her from going on a summer vacation. However, it was after finishing her second year that she made a heartfelt decision. On June 1, 1888, Susan arrived back home at the Banroft station where she had embarked on her journey to Philadelphia nearly two years prior. However, her return was met with a somber reality. The year had brought upon the community a “terrible scourge of measles” that had devastating consequences. The toll was immeasurable, with 87 lives lost, mostly innocent children. Susan was confronted with the unimaginable scale of suffering and loss. Throughout the long summer, she dedicated herself to caring for the people in her community. Some of them were hesitant to take medicines, so Susan patiently explained to them the importance of proper treatment for the illness. She knew that she needed to support her family and friends during this challenging time. However, Susan also remained steadfast in her commitment to complete her medical studies. With a heavy heart, she bid farewell to her loved ones and returned to college.28

Susan maintained regular correspondence with her family. Whenever her loved ones shared their medical concerns, Susan readily offered her expertise and guidance, providing valuable advice and suggesting appropriate treatments.29

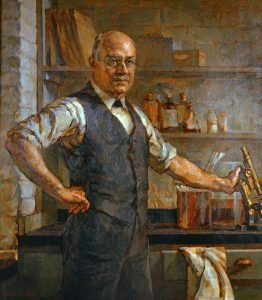

Miss Sue’s unwavering dedication paid off as she successfully passed all of her exams during the challenging three years of medical school. And on that remarkable day of March 14, 1889, at the young age of twenty-four, Susan’s remarkable academic journey culminated in her well-deserved distinction as the highest-ranking student in her medical college, earning the prestigious title of valedictorian. Her achievement was not only remarkable but also historic, as she emerged as the pioneering American Indian physician in the entire nation. She achieved this momentous milestone an impressive 31 years prior to when women were granted the vote and 35 years before all American Indians were granted full citizenship in their own homeland.30

Following her graduation, Susan’s pursuit of excellence continued unabated. Determined to further her medical career, she applied for a respected position as a resident surgeon at the Hospital for female patients. The competition was tough, but Susan’s hard work paid off when she achieved one of the six spots available for the prestigious four-month internship.31

Miss Sue achieved her dream. As Dr. Sue, she came back to her homeland and worked tirelessly to educate them about important health practices like cleanliness and safe food. Now equipped with knowledge about medicines, she could explain their properties, write prescriptions, stitch wounds, and treat illnesses like measles, influenza, pneumonia, and tuberculosis. Dr. Susan emphasized the importance of hygiene, a healthy diet, exercise, and fresh air. She even performed minor surgeries, set bones, and conducted autopsies. By implementing simple changes such as banning public cups for drinking beverages and installing nets on windows for better airing and protection against the flies that carry diseases, she significantly reduced the mortality rates among her people. Dr. Susan made a huge contribution to public health and Omaha people’s new life.32

Thereafter, Susan bore two sons, fulfilling her desire to be a mother. “Motherhood is a privilege,” she had written years before.33 Susan was a devoted mother to her two cherished sons. At the same time, she worked as a doctor because her community admired and relied on her to help them whenever they needed. But that is another good story to tell about this fascinating woman.

- Christopher Klein, “Remembering the First Native American Woman Doctor,” HISTORY, July 11, 2023, https://www.history.com/news/remembering-the-first-native-american-woman-doctor. ↵

- Vida Stabler, “History of Dr. Susan,” Dr. Susan La Flesche Picotte Center, accessed March 1, 2024, https://picottecenter.org/dr-susan. ↵

- Thomas Kennard “‘If You Knew the Conditions…’ Health Care to Native Americans: United States 19th-Century Doctors Thoughts about Native American Medicine,” Exhibitions (U.S. National Library of Medicine), accessed March 3, 2024, https://www.nlm.nih.gov/exhibition/if_you_knew/ifyouknew_04.html. ↵

- Joe Starita, A Warrior of the People: How Susan La Flesche overcame racial and gender inequality to become America’s first Indian doctor (New York: St. Martin’s Publishing Group, 2016), 32-33. ↵

- Joe Starita, A Warrior of the People: How Susan La Flesche overcame racial and gender inequality to become America’s first Indian doctor (New York: St. Martin’s Publishing Group, 2016), 75. ↵

- Joe Starita, A Warrior of the People: How Susan La Flesche overcame racial and gender inequality to become America’s first Indian doctor (New York: St. Martin’s Publishing Group, 2016), 98. ↵

- Joe Starita, A Warrior of the People: How Susan La Flesche overcame racial and gender inequality to become America’s first Indian doctor (New York: St. Martin’s Publishing Group, 2016), 99. ↵

- Mariel Tishma, “Dr. Susan LaFlesche Picotte: Tradition, Assimilation, and Healing”, Hektoen International – A Journal of Medical Humanities, November 12, 2021, https://hekint.org/2021/11/12/dr-susan-laflesche-picotte-tradition-assimilation-and-healing/. ↵

- Mariel Tishma, “Dr. Susan LaFlesche Picotte: Tradition, Assimilation, and Healing”, Hektoen International – A Journal of Medical Humanities, November 12, 2021, https://hekint.org/2021/11/12/dr-susan-laflesche-picotte-tradition-assimilation-and-healing/. ↵

- Joe Starita, A Warrior of the People: How Susan La Flesche overcame racial and gender inequality to become America’s first Indian doctor (New York: St. Martin’s Publishing Group, 2016), 119. ↵

- Mariel Tishma, “Dr. Susan LaFlesche Picotte: Tradition, Assimilation, and Healing”, Hektoen International – A Journal of Medical Humanities, November 12, 2021, https://hekint.org/2021/11/12/dr-susan-laflesche-picotte-tradition-assimilation-and-healing/. ↵

- Mariel Tishma, “Dr. Susan LaFlesche Picotte: Tradition, Assimilation, and Healing”, Hektoen International – A Journal of Medical Humanities, November 12, 2021, https://hekint.org/2021/11/12/dr-susan-laflesche-picotte-tradition-assimilation-and-healing/. ↵

- Joe Starita, A Warrior of the People: How Susan La Flesche overcame racial and gender inequality to become America’s first Indian doctor (New York: St. Martin’s Publishing Group, 2016), 125. ↵

- Joe Starita, A Warrior of the People: How Susan La Flesche overcame racial and gender inequality to become America’s first Indian doctor (New York: St. Martin’s Publishing Group, 2016), 36. ↵

- Joe Starita, A Warrior of the People: How Susan La Flesche overcame racial and gender inequality to become America’s first Indian doctor (New York: St. Martin’s Publishing Group, 2016), 36. ↵

- Joe Starita, A Warrior of the People: How Susan La Flesche overcame racial and gender inequality to become America’s first Indian doctor (New York: St. Martin’s Publishing Group, 2016), 37. ↵

- Joe Starita, A Warrior of the People: How Susan La Flesche overcame racial and gender inequality to become America’s first Indian doctor (New York: St. Martin’s Publishing Group, 2016), 37. ↵

- Mariel Tishma, “Dr. Susan LaFlesche Picotte: Tradition, Assimilation, and Healing”, Hektoen International – A Journal of Medical Humanities, November 12, 2021, https://hekint.org/2021/11/12/dr-susan-laflesche-picotte-tradition-assimilation-and-healing/. ↵

- Joe Starita, A Warrior of the People: How Susan La Flesche overcame racial and gender inequality to become America’s first Indian doctor (New York: St. Martin’s Publishing Group, 2016), 137. ↵

- Joe Starita, A Warrior of the People: How Susan La Flesche overcame racial and gender inequality to become America’s first Indian doctor (New York: St. Martin’s Publishing Group, 2016), 140. ↵

- Lisa Spellman, “Honoring Dr. Susan La Flesche Picotte,” Newsroom, November 19, 2020, https://www.unmc.edu/newsroom/2020/11/19/honoring-dr-susan-la-flesche-picotte/. ↵

- Joe Starita, A Warrior of the People: How Susan La Flesche overcame racial and gender inequality to become America’s first Indian doctor (New York: St. Martin’s Publishing Group, 2016), 143. ↵

- Joe Starita, A Warrior of the People: How Susan La Flesche overcame racial and gender inequality to become America’s first Indian doctor (New York: St. Martin’s Publishing Group, 2016), 145-146. ↵

- Joe Starita, A Warrior of the People: How Susan La Flesche overcame racial and gender inequality to become America’s first Indian doctor (New York: St. Martin’s Publishing Group, 2016), 155-156. ↵

- Princella Parker, “Making Invisible Histories Visible / Dr. Susan LaFlesche Picotte – Native American Doctor,” accessed March 17, 2024, https://www.ops.org/Page/http%3A%2F%2Fwww.ops.org%2Fsite%2Fdefault.aspx%3FPageID%3D1887. ↵

- Joseph Agonito, Brave hearts: Indian women of the Plains (Guilford, Connecticut: TwoDot, 2017), 179. ↵

- Benson Tong, Susan La Flesche Picotte, M.D.: Omaha Indian Leader and Reformer (University of Oklahoma Press, 2000), 71-72. ↵

- Joe Starita, A Warrior of the People: How Susan La Flesche overcame racial and gender inequality to become America’s first Indian doctor (New York: St. Martin’s Publishing Group, 2016), 162-163. ↵

- Benson Tong, Susan La Flesche Picotte, M.D.: Omaha Indian Leader and Reformer (University of Oklahoma Press, 2000), 77. ↵

- Joe Starita, A Warrior of the People: How Susan La Flesche overcame racial and gender inequality to become America’s first Indian doctor (New York: St. Martin’s Publishing Group, 2016), 170. ↵

- Joe Starita, A Warrior of the People: How Susan La Flesche overcame racial and gender inequality to become America’s first Indian doctor (New York: St. Martin’s Publishing Group, 2016), 171. ↵

- Joe Starita, A Warrior of the People: How Susan La Flesche overcame racial and gender inequality to become America’s first Indian doctor (New York: St. Martin’s Publishing Group, 2016), 174. ↵

- Lisa M. Bellecci, “Her story – Susan LaFlesche Picotte – Feminists for Life,” accessed March 18, 2024, https://www.feministsforlife.org/herstory-susan-laflesche-picotte/. ↵

40 comments

Alemkhan

Great job ?

Azat

Amazing!!

Julia

Great article and please post more like this.

Tameris Mak

So amazing post????

Таня

cool explanation, I really like it and I clearly got the idea

Tomiris

Super!

amir

pretty interesting

Алина Айдархан

so much useful information, very inspiring, really demand more!!

Dilya

Janel, very good job??

Temujin

Great article! Very interesting and detailed!