It was February 1939, and Alan Turing was sitting in his office at Bletchley Park, surrounded by documents, meticulously studying sheets with numbers and letters, trying to decipher them and make sense of them. It was like a maze with no way out. They were encrypted messages from the Germans, coded by a machine known as Enigma, operated by the Germans. The machine could encrypt any message, and it would be unbreakable.1

During World War II, the Germans were utilizing the Enigma machine to encrypt their military strategies and classified information. However, many people believed that these messages could only be understood by the Germans because they were virtually impossible to decipher.2 But Turing was determined to prove those people wrong. He was intrigued by the opportunity to aid the British in their war against Germany.

Before Alan Turing was recruited to Bletchley Park, Polish scientists had been working for three years to decipher German messages. They failed at first, but ultimately they discovered the fact that the cryptography had been changed by an automated cipher machine called the Enigma. However, mathematicians found the method of decoding and encoding a secret message a fascinating challenge. By early 1938, 75% of the messages sent by the German armed forces were capable of being read by the Poles. The Poles then shared their technology and all their advances with British and French operatives just days before the beginning of World War II, even sending an upgraded Enigma machine to London.3 And this is when Alan Turing arrived, in 1939 at Bletchley Park, although Alan had already been working to decipher the Enigma code.

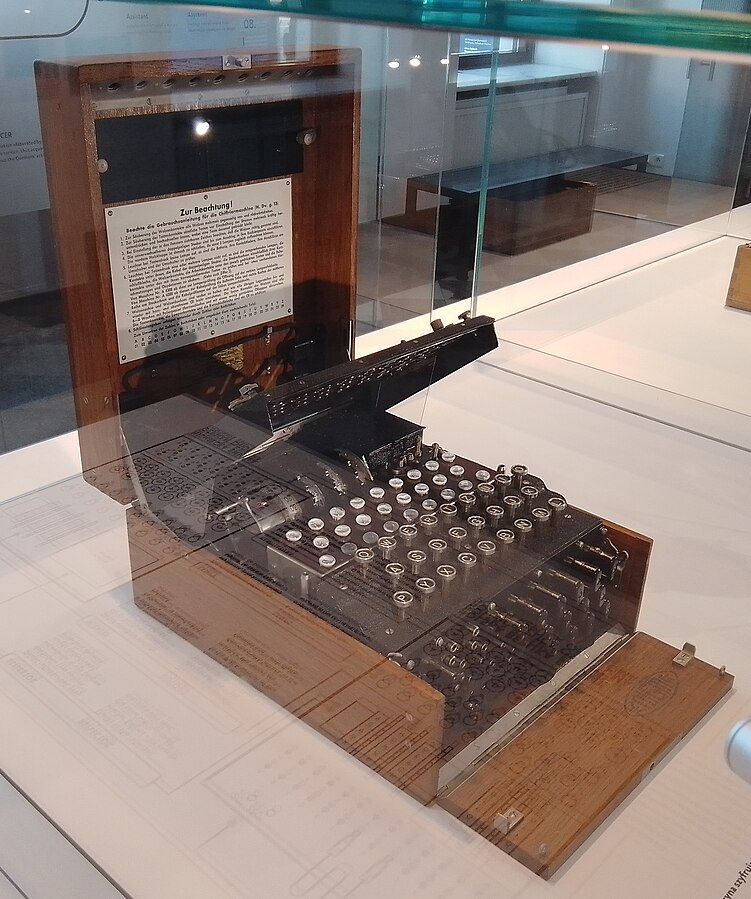

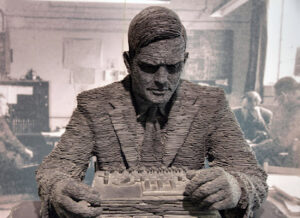

The Enigma machine resembled a typewriter featuring a keyboard with 26 letters and an additional set of 26 lettered lights. The German military possessed around 40,000 Enigma machines distributed among all army units. Following two years of warfare, the British government sought individuals in mathematics and modern languages at Oxford. Faced with a shortage of qualified candidates, they recruited some non-linguistic people from Oxford and Cambridge universities. Among these few was Alan Mathison Turing, the future father of the modern computer, computer science, software, artificial intelligence, the Turing machine, and the Turing test as well, and who contributed to the contemporary Bayesian resurgence.4 Turing studied mathematics at Cambridge and Princeton universities, but his passion was logic and the concrete world, which is something to admire because, with his passion, imagination, and vision, he became an important figure in the technological field.

On September 4, the day following England’s declaring war on Germany, Turing boarded a train to travel to the CG&CS research facilities located at Bletchley Park, a small village situated north of London. Although he seemed sixteen, he was actually twenty-seven years old. He was described as a shy, athletic, and attractive man. At Cambridge, he was openly homosexual. His appearance did not matter to him; he had dirty fingernails and a permanent five o’clock shadow. He did not know that for the following six years he would work on collab projects.5 He knew that deciphering the Enigma code could provide the Allies with a significant advantage, potentially saving millions of Allied lives. However, he faced a daunting challenge: the Germans changed their settings every day, and British intelligence was consistently lagging and were at a constant disadvantage. Then came Alan at a moment that would change everything.6 Turing had a brilliant idea and designed the Bombe machine, capable of deciphering the Enigma code faster than any human. This breakthrough offered hope to all involved in decryption efforts, breathing new life into their mission.

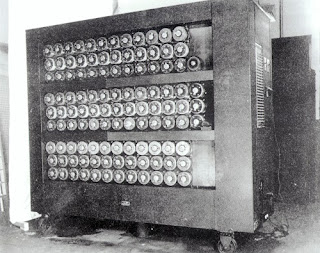

The Bombe was a huge machine that had 108 rotating drums that spun thousands of times to reproduce the movements of the rotors that were in the Enigma, making different decryption patterns beyond human capability. The Bombe also had the ability to simultaneously emulate thirty-six Enigma machines. And it was something very special for Alan, because with this, he could decipher something that had been attempted for years but had not been achieved. Turing’s machine would test hunches that were created with a theoretical device capable of performing computations that could be done algorithmically. This machine tested various combinations and strategies to uncover the message. It suggested fifteen fragments of suspicious letters that might be part of the original message. This pattern was crucial in determining whether or not these fragments were included and could help break the code.7

The machine provided an alternative to manual testing, which would have required testing numerous possible attempts over thousands of words. With the machine, they gained an advantage by finding faster and more accurate matches directly. This was often quicker than eliminating words that didn’t fit the deciphering patterns they were using. The Bombe was an electromechanical device designed to aid in codebreaking by using rotors to identify and eliminate combinations of letters that didn’t match. Turing collaborated with mathematician Gordon Welchman and others to continually improve and refine the machine throughout the war. This iterative process significantly enhanced deciphering capabilities and greatly contributed to the Allied effort. Alan and his team no longer had to manually examine each letter; the Bombe machine handled that task for them.8 However, the Germans had suspected that someone was trying to break their code, so every day, they changed the combination of letters on the rotors and eventually added an extra rotor to increase the complexity of the code and make it harder to decipher.

One day in late May 1942, Turing received an urgent message from his colleague, Joan. Joan had noticed a pattern in the German messages: they always started with the same three letters, which he suspected were the initials of the operators. He suggested that Turing use this information to narrow down the possible settings of the Enigma machines. Turing was intrigued by Joan’s idea and decided to test it out.9 He modified the Bombe machine to look for messages that started with the same three letters and then he tried to match them with the corresponding Enigma settings. He ran the Bombe machine for several hours until one of them stopped with a loud click. Turing rushed to the machine and checked the results. He couldn’t believe his eyes: he had found the settings for the German naval Enigma, the most secure and elusive of all.

Turing quickly decoded the message and read it with astonishment. It was a top-secret order from the German High Command, instructing the battleship Bismarck to break out of the Atlantic and head for the French port of Brest. The Bismarck was the most powerful and feared warship in the world, and its escape would be a devastating blow to the British navy.10

For the first time, Bletchley Park could read U-boat messages within an hour of their arrival. This marked a turning point in the war, as the British could now safely divert convoys around U-boats, preventing further losses.11 The tension and excitement surrounding the Allied success against the Enigma code came at a cost to Alan Turing. Alan did not get any recognition for the key role he played.

Alan Turing, the brilliant mathematician and computer scientist, faced a harsh destiny due to society’s stereotypes. In spite of his heroic achievements in cryptography during the war, in 1952, he was convicted of homosexuality, a crime under British law at that time. Faced with the choice between prison or treatment with female hormones, Turing opted for the second option. The treatment led to his isolation and ultimately contributed to his untimely death. Despite this tragedy, Turing’s legacy lives on. His work to decipher the Enigma code during World War II played a critical role in the Allied victory. Beyond his contributions to science, Turing challenges us to confront prejudice and break down barriers. His brilliance transcends time and has inspired generations of engineers, computer scientists, and mathematicians to work toward a better and more inclusive society.12

- Andrew Hodges, Alan Turing: The Enigma (Princeton University Press, January 1, 2014), 211. ↵

- David Kahn, “Codebreaking in World Wars I and II: The Major Successes and Failures, Their Causes and Their Effects,” The Historical Journal 23, no. 3 (1980): 624. ↵

- David Kahn, “Codebreaking in World Wars I and II: The Major Successes and Failures, Their Causes and Their Effects,” The Historical Journal 23, no. 3 (1980): 629. ↵

- Sharon Bertsch McGrayne, The Theory That Would Not Die : How Bayes’ Rule Cracked the Enigma Code, HuntedDown Russian Submarines, and Emerged Triumphant From Two Centuries of Controversy (New Haven, Conn: Yale University Press, 2011), 62. ↵

- Sharon Bertsch McGrayne, The Theory That Would Not Die : How Bayes’ Rule Cracked the Enigma Code, Hunted Down Russian Submarines, and Emerged Triumphant From Two Centuries of Controversy (New Haven, Conn: Yale University Press, 2011), 65. ↵

- Algis Valiunas, “Turing and the Uncomputable,” The New Atlantis, no. 61 (2020): 62. ↵

- Sharon Bertsch McGrayne, The Theory That Would Not Die : How Bayes’ Rule Cracked the Enigma Code, Hunted Down Russian Submarines, and Emerged Triumphant From Two Centuries of Controversy (New Haven, Conn: Yale University Press, 2011), 77. ↵

- Sharon Bertsch McGrayne, The Theory That Would Not Die : How Bayes’ Rule Cracked the Enigma Code, Hunted Down Russian Submarines, and Emerged Triumphant From Two Centuries of Controversy (New Haven, Conn: Yale University Press, 2011), 67. ↵

- Andrew Hodges, Alan Turing: The Enigma (Princeton University Press, January 1, 2014), 296. ↵

- Andrew Hodges, Alan Turing: The Enigma (Princeton University Press, January 1, 2014), 301. ↵

- Algis Valiunas, “Turing and the Uncomputable,” The New Atlantis, no. 61 (2020): 64. ↵

- “Alan Turing’s Legacy: Editorial,” New York Times, Late Edition (East Coast), June 23, 2012, sec. A. ↵

5 comments

Sebastian Hernandez-Soihit

This article truly deminstrate just how much technological advancement was prompted by WWII and the good humanity was able to derive from the most terrifying conflict in world history. Truly heartbreaking how his homosexuality overshadowed his achievements to the eyes of the law. Primary sources are engaging and good narrative devices are employed, outstanding!

Sebastian Hernandez-Soihit

This article truly deminstrate just how much technological advancement was prompted by WWII and the good humanity was able to derive from the most terrifying conflict in world history. Truly heartbreaking how his homosexuality overshadowed his achievements to the eyes of the law. Very good images and pictures shared- great job!

Carlos Anthony Alonzo

Your article on Alan Turning is truly impressive, offering valuable insights into the achievements and untimely death. The depth of your analysis and the clarity of your arguments make a compelling case for the importance of your work. I commend you on your telling of this remarkable story with your thoughtful interpretation of his life. Keep up the excellent work!

Maria Fernanda Guerrero

Thank you Areli for writing about Alan Turing, a historic hero that not enough people know about. Through his hard work we were able to get the upper hand from Germany. Due to Alan’s recreation and his ability to decipher the Germans codes, he became one of the major factors that led the British to victory. Nonetheless, despite his contribution to his country he was being charged for being homosexual and was getting sent to prison. However, they possessed an ultimatum to him either go to prison or take female hormones. I am shocked and disgusted by the cruelty. Couldn’t the country look the other way? Areli, congratulations on your article, it was a fascinating piece. You truly got me invested.

qmero

Well done! Alan Turing is a remarkably under-credited hero of the Second World War, so I appreciate your article bringing him recognition. It was tragic to learn about Turing’s unjust criminal charges and his resulting untimely death soon after. England had done a great disservice to one of their country’s greatest heroes when they convicted Turing of simply being himself.