Jackson’s Background and Past with the Banks

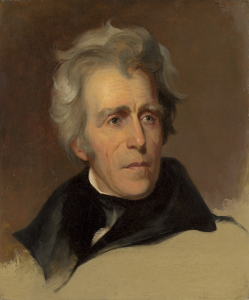

Our story begins with Andrew Jackson, born March 15, 1767, South Carolina was an esteemed military hero and the seventh president of the United States (1829–37). Jackson was the first U.S. president to come from the area west of the Appalachians and the first to gain office by a direct appeal to the mass of voters. His political movement has since been known as Jacksonian Democracy.1

South Carolina offered little opportunity for formal education, and what schooling Jackson received was interrupted by the British invasion of the western Carolinas in 1780–81. In the latter year, he was captured by the British. Shortly after being imprisoned, he refused to shine the boots of a British officer and was struck across the face with a sabre. His mother and two brothers died during the closing years of the war as direct or indirect casualties of the invasion of the Carolinas. This sequence of tragic experiences fixed in Jackson’s mind a lifelong hostility toward Great Britain.2

After the end of the American Revolution, he studied law in an office in Salisbury, North Carolina, and was admitted to the bar of that state in 1787. In 1788, he went to the Cumberland region as prosecuting attorney of the western district of North Carolina. He was so successful in these litigations that he soon had a thriving private practice and gained the friendship of landowners and creditors. Jackson had made significant progress in his pursuit of politics.3

Early Political Life

Jackson’s interest in public affairs and in politics had always been keen. He had gone to Nashville as a political appointee, and in 1796, he became a member of the convention that drafted a constitution for the new state of Tennessee. In the same year, he was elected as the first representative from Tennessee to the U.S. House of Representatives. An undistinguished legislator, he refused to seek reelection and served only until March 4, 1797. Jackson returned to Tennessee, vowing never to enter public life again, but before the end of the year, he was elected to the U.S. Senate. His willingness to accept the office reflects his emergence as an acknowledged leader of one of the two political factions contending for control of the state. Nevertheless, Jackson resigned from the Senate in 1798 after an uneventful year. Soon after his return to Nashville he was elected a judge of the superior court (in effect, the supreme court) of the state and served in that post until 1804. In 1802, Jackson had also been elected major general of the Tennessee militia, a position he still held when the War of 1812 opened the door to a command in the field and a hero’s role.4

Military Successes

The frontiersman was always ready for a fight, and just now he especially wanted a fight with England. He resented the insults that his country had suffered at the hands of the English authorities.5 In March 1812, when it appeared that war with Great Britain was imminent, Jackson issued a call for 50,000 volunteers to be ready for an invasion of Canada. After the declaration of war, in June 1812, Jackson offered his services and those of his militia to the United States. The government was slow to accept this offer, and, when Jackson finally was given a command in the field, it was to fight against the Creek Indians, who were allied with the British and who were threatening the southern frontier. In a campaign of about five months, in 1813–14, Jackson crushed the Creeks, the final victory coming in the Battle of Tohopeka, otherwise known as Horseshoe Bend, in Alabama. The victory was so decisive that the Creeks never again menaced the frontier. Jackson was established as the hero of the West. These revelations brought joy and relief to the American people and made Jackson the hero not only of the West but of a substantial part of the country as well.6

Beginning of Jackson’s Time in Office

Jackson’s military triumphs led to suggestions that he become a candidate for president, but he disavowed any interest, and political leaders in Washington assumed that the flurry of support for him would prove transitory. The campaign to make him president, however, was kept alive by his continued popularity and was carefully nurtured by a small group of his friends in Nashville, who combined devotion to the general with a high degree of political astuteness. In 1822, these friends maneuvered the Tennessee legislature into a formal nomination of their hero as a candidate for president. In the following year, this same group persuaded the legislature to elect him to the U.S. Senate—a gesture designed to demonstrate the extent of his popularity in his home state.7

In the election of 1824, four candidates received electoral votes. Jackson received the highest number (99); the others receiving electoral votes were John Quincy Adams (84), William H. Crawford (41), and Henry Clay (37). Because no one had a majority, the House of Representatives was required to elect a president from the three with the highest number of votes. Crawford was critically ill, so the frontrunners were Jackson, Adams, and Clay. Clay, as speaker of the House, was in a strategic and perhaps decisive position to determine the outcome, and he threw his support to Adams, who was elected on the first ballot. When Adams appointed Clay Secretary of State, it seemed to admirers of Jackson to confirm rumors of a “corrupt bargain” between Adams and Clay. Jackson’s friends persuaded him that the popular will had been thwarted by intrigues. Jackson was determined to vindicate himself and his supporters by becoming a candidate again in 1828.8

In the election of 1828, Jackson defeated Adams by an electoral vote of 178 to 83 after a campaign in which personalities and slander played a larger part than in any previous U.S. national election. Jackson and his wife, Rachel, despite their long marriage, had been vilified in campaign pamphlets as adulterers. The basis was that Rachel Jackson was not legally divorced from her first husband at the time she and Jackson were wed. When they discovered their mistake, they remarried, but the damage had been done.9

Jackson’s election to the presidency in 1828 was correctly described by Senator Benton as “a triumph of democratic principle, and an assertion of the people’s right to govern themselves,” emphasizing that Jackson’s election represented the success of the democratic system over elitist or aristocratic control.10 Jackson’s hour of triumph was soon overshadowed by personal tragedy—his wife died at the Hermitage on December 22, 1828.11

Jackson was the first president born in poverty. In time, he became one of the largest landholders in Tennessee, yet he had retained the frontiersmen’s prejudice against people of wealth. Jackson had no well-defined program of action when he entered the presidency. He was the beneficiary of a rising tide of democratic sentiment, a trend that was aided by the admission of six new states to the Union, five of which had manhood suffrage, and by the extension of the suffrage laws by many of the older states. As the power of the older political organizations weakened, the way was opened for the rise of new political leaders skilled in appealing to the masses of voters. Not the least remarkable triumph of the Jacksonian organization was its success in picturing its candidate as the embodiment of democracy, despite the fact that Jackson had been aligned with the conservative faction in Tennessee politics for thirty years, and that in the financial crisis that swept the West after 1819, he had vigorously opposed legislation for the relief of debtors.12

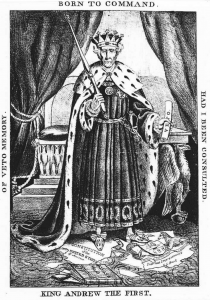

Jackson was the first president since George Washington who had not served a long apprenticeship in public life and had no personal experience in the formulation or conduct of foreign policy. Our protagonist met each issue as it arose, and he exhibited the same vigor and determination in carrying out decisions that had characterized his conduct as commander of an army. He made it clear from the outset that he would be the master of his own administration, and, at times, he was so strong-willed and decisive that his enemies referred to him as “King Andrew I.”13

The Opposition – Henry Clay and Nicholas Biddle

Nicholas Biddle, a Philadelphia lawyer-diplomat, succeeded Langdon Cheves as president of the Second Bank of the United States in 1823, and an era of great prosperity set in. Biddle played a vital role in the development of America’s financial system. Biddle sought the banks to be integral for nationwide stability while Jackson’s opinion differed.14

Henry Clay was a renowned member of both the House of Representatives and the Senate, and established leader of the National Republicans. Clay challenged Jackson for office in 1824 and again in 1832. Similar to Biddle, Clay figured the banks to be essential for the stability of the nation. Henry Clay figured more power should be placed with the government while Jackson wanted to decentralize the government.

Political Maneuvering

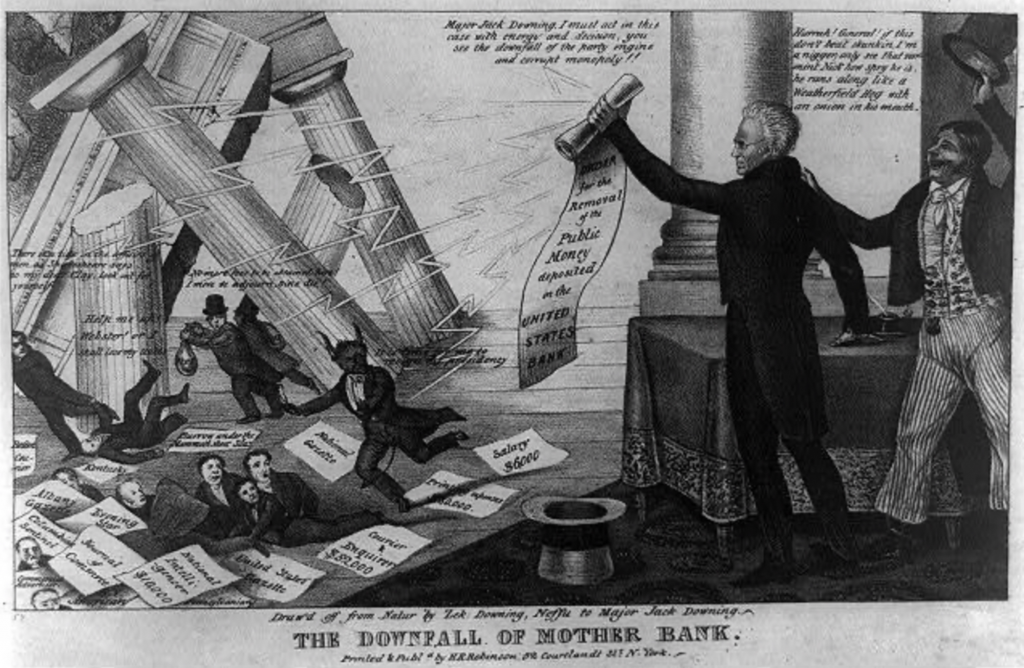

Our antagonists, Biddle and Clay, hoped to further embarrass Jackson by posing a new dilemma. The Charter of the Bank of the United States was due to expire in 1836. The president had not clearly defined his position on the bank, but he was increasingly uneasy about how it was then organized. More significant was the fact that large factions of voters who favored Jackson were openly hostile to the bank. Jackson’s opponents rushed through Congress a bill to recharter it. The move, led by Kentucky Senator and former Speaker of the House Henry Clay, who would become his challenger for the upcoming election, forced Jackson to choose between signing the measure and alienating supporters or vetoing the bill and appearing to be an adversary to the unjust banking practices. Jackson ultimately vetoed the bill on July 10, 1832. His opponents raged that a failure to renew the charter would have devastating consequences for the economy. However, Jackson’s denunciation of the bank’s reputation as a bastion of entrenched power was well-received by voters.15

Jackson’s cabinet was divided between friends and critics of the bank, but the obvious political motives of the recharter bill reconciled all of them to the necessity of a veto. The question before Jackson was whether the veto message should leave the door open to future compromise. It is worth noting that few presidential vetoes have caused as much controversy in their own time or later as the one Jackson sent to Congress on July 10, 1832. The veto of the bill to recharter the bank was the prelude to a conflict over financial policy that continued through Jackson’s second term.16

The Outline of the Bank

The central bank was to differ from the commercial banks. One distinguishing feature that central banks were granted was the ability to regulate the nation’s money supply and credit. The Bank of the United States would act as the Treasury Department’s fiscal agent, collecting revenues and disbursing payments. In this role, the bank would naturally hold the country’s specie reserves and was expected to provide a sound national currency. Given these functions, the bank would be the main force regulating commercial credit and the health of the country’s banking system. In 1815 Secretary of the Treasury Alexander J. Dallas articulated the following on the grounds of the charter of the Second Bank “Ought not to be regarded as a commercial bank. It will not operate upon the funds of the stockholders alone, but much more upon the funds of the nation. Its conduct, good or bad, will not affect corporate credit alone, but much more the credit and resources of the government. In fine, it is not an institution created for the purposes of commerce and profit alone, but much more for the purposes of national policy, as an auxiliary in the exercise of some of the highest powers of government.”17 Dallas implemented Alexander Hamilton’s vision, which was for the National Bank to serve as an integral piece of national policy rather than a profit-driven capitalist company.

Principles Against Immorality

Jackson seems to have carried to Washington in 1829 a deep distrust of the Bank, and he was disposed to speak out boldly against it in his inaugural address. But he was persuaded by his friends that this would be ill-advised, and he therefore made no mention of the subject. Yet he made no effort to conceal his attitude, for he wrote to Biddle a few months after the inauguration that he did not believe that Congress had the power to charter a bank outside of the District of Columbia, that he did not dislike the United States Bank more than other banks, but that ever since he had read the history of the South Sea Bubble he had been afraid of banks.18

Biddle labored manfully to stem the tide. He tried to improve his personal relations with the President, and he even allowed Jackson’s men to gain control of several of the western branches. The effort, however, was in vain.19 The Bank was regarded as a great financial monopoly, an “octopus,” and Biddle as an autocrat bent only on dominating the entire banking and currency system of the country.20

In Jackson’s veto message regarding the Bank of the United States, Jackson asserts, “It is to be regretted that the rich and powerful too often bend the acts of government to their selfish purposes.”21 In response, Biddle believed the banks not to be some tool for the wealthy elite but rather an institution that oversees the currency, prevents inflation, and allows for reliable credit.

In a set of autograph notes from which the second message was prepared, the existing Bank was declared not only unconstitutional but dangerous to liberty, “because through its officers, loans, and participation in politics, it could build up or pull down parties or men, because it created a monopoly of the money power, because much of the stock was owned by foreigners, because it would always support him who supported it, and because it weakened the state and strengthened the general government.” Congress paid no attention to either criticisms or recommendations. Due to Congress and their lack of concern on the matter, the supporters of the Bank took fresh heart.22

In Jackson’s veto message regarding the Bank of the United States, Jackson proclaimed, “There are no necessary evils in government. Its evils exist only in its abuses. If it would confine itself to equal protection, and, as Heaven does its rains, shower its favors alike on the high and the low, the rich and the poor, it would be an unqualified blessing. In the act before me, there seems to be a wide and unnecessary departure from these just principles.”23 Jackson compares this ideology of equal protection to rain, how rain from the heavens is dispersed equally upon both the wealthy and the impoverished.

To destroy the United States Bank was a different matter, for this institution had the full support of one of the two great parties in which the people of the country were now grouped: Jackson’s own party was by no means a unit in opposing it; and the prestige and influence of the Bank were such as to enable it to make a powerful fight against any attempts to annihilate it.24

The Second Bank of the United States utilized the federal deposits granted by the government. Jackson, using his executive power, distributed the federal funds to his state-chartered banks.25 Despite Biddle’s handicap as president of the Second Bank, he still maintained control over his banks. To exact retribution against Jackson’s efforts, Biddle and his party painted Jackson as a reckless tyrant who continuously neglected the Constitution.

Jackson upheld his promises and on the 10th of July, the bill was vetoed. The message, however, was intended as a campaign document, and as such it showed great ingenuity. It attacked the Bank as a monopoly, a “hydra of corruption,” and an instrumentality of federal encroachment on the rights of the States. Clay then pronounced Jackson’s construction of the veto power “irreconcilable with the genius of representative government.”26

The Election of 1832

Jackson was still a popular leader as he approached the end of his first term in office, but his administration was fractured by a personal conflict with his vice president, John C. Calhoun.27 The National Republicans, whose nominee was Clay, defended the institution and attacked the veto; the Jacksonians reiterated on the stump every charge and argument that their leader had taught them. The verdict was decisive. Jackson received 219 and Clay 49 electoral votes.28

This was a great victory. This achievement was the direct result of Jackson’s effort, strategy, and passion. The President was unquestionably right in interpreting his triumph as an endorsement of the veto, and he naturally felt that the question was settled. The officers and friends of the Bank still hoped, however, to snatch victory from defeat. In conclusion, they had no expectation of converting Jackson or of carrying a charter measure at an early date. Though the National Republicans attempted to paint Jackson’s positions as unconstitutional, his reform agenda remained popular, and he won a second term by a wide margin.29

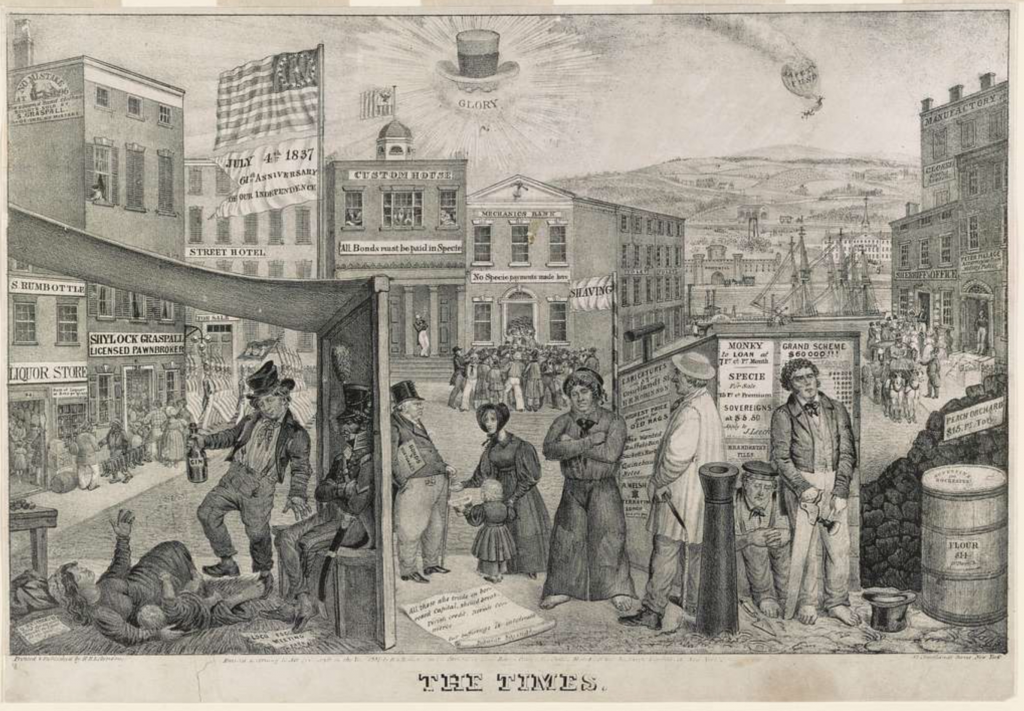

Efforts to persuade Congress to enact legislation limiting the circulation of bank notes had failed, but there was one critical point at which Jackson was free to apply his theories. From then on, all purchasers of public lands paid with bank notes. Jackson issued the Specie Circular in July 1836, requiring payment in gold or silver for all public lands. This measure created a demand for specie that many of the banks could not meet; banks began to fail, and the effect of bank failures in the West spread to the East. By the spring of 1837, the entire country was gripped by a financial panic. The panic did not come, however, until after Jackson had the pleasure of seeing Martin Van Buren inaugurated as president on March 4, 1837. Jackson retired to his home, the Hermitage. For decades in poor health, he was virtually an invalid during the remaining eight years of his life, but he continued to have a lively interest in public affairs.30

The Panic of 1837

By this time, Jackson was no longer in office, and what had been done could not be undone. Jackson fought hard for the common people, refusing to allow the corrupt institution to dictate the lives of others. The Panic of 1837 was a major recession in the US economy that began in the spring of 1837 and lasted until the mid-1840s. During the “panic,” also referred to as “hard times,” hundreds of banks collapsed, the currency lost value as prices soared, and farmers, merchants, and business owners across the country suffered severe financial losses or ruin.31

President Andrew Jackson vetoed the rechartering of the Bank of the United States—and to speed its demise, redistributed federal funds among smaller state-chartered banks across the country. The lack of a national bank meant little national regulation or oversight of banking practices. President Jackson issued the Specie Circular, an executive order mandating that federal land be purchased with specie, not paper currency.33

Paper money would no longer be accepted, only specie or “hard currency” would be admissible. To add, the Coinage Act of 1834 only served to complicate the situation further. The act differentiated the worth of foreign gold from Great Britain, Portugal, and Brazil, by both carat and pennyweight. Some of the foreign coins were less in “fineness,” meaning the coins had less carat, thus making the coins not minted or the US standard. The gold coins from France, Spain, and Mexico were overvalued comparatively speaking. Furthermore, the currency of less purity was prone to misleading the public, and availability for recoinage was raised.34

The Panic of 1837 was a widespread financial crisis that devastated the United States. The crucial factor in this economic decline was the unregulated state-chartered banks. Andrew Jackson’s veto of the bank’s recharter bill alongside the Coinage Act of 1834 were both components of the nationwide recession. The Panic of 1837 marked a time of great hardship and sorrow, businesses were collapsing, the currency lost its value, unemployment was at an all-time high, and many citizens starved.

- Harold Whitman Bradley, “Andrew Jackson,” Encyclopedia Britannica, 2024, accessed December 14, 2024, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Andrew-Jackson#ref3613. ↵

- Harold Whitman Bradley, “Andrew Jackson,” Encyclopedia Britannica, 2024, accessed December 14, 2024, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Andrew-Jackson#ref3613. ↵

- Harold Whitman Bradley, “Andrew Jackson,” Encyclopedia Britannica, 2024, accessed December 14, 2024, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Andrew-Jackson#ref3613. ↵

- Harold Whitman Bradley, “Andrew Jackson,” Encyclopedia Britannica, 2024, accessed December 14, 2024, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Andrew-Jackson#ref3613. ↵

- Frederic Austin Ogg, The Reign of Andrew Jackson: A Chronicle of the Frontier in Politics (New Haven, Conn: Yale Univ Press, 1920), 25. ↵

- Harold Whitman Bradley, “Andrew Jackson,” Encyclopedia Britannica, 2024, accessed December 14, 2024, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Andrew-Jackson#ref3613. ↵

- Harold Whitman Bradley, “Andrew Jackson,” Encyclopedia Britannica, 2024, accessed December 14, 2024, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Andrew-Jackson#ref3613. ↵

- Harold Whitman Bradley, “Andrew Jackson,” Encyclopedia Britannica, 2024, accessed December 14, 2024, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Andrew-Jackson#ref3613. ↵

- Harold Whitman Bradley, “Andrew Jackson,” Encyclopedia Britannica, 2024, accessed December 14, 2024, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Andrew-Jackson#ref3613. ↵

- Frederic Austin Ogg, The Reign of Andrew Jackson: A Chronicle of the Frontier in Politics (New Haven, Conn: Yale Univ Press, 1920), 113. ↵

- Richard Pallardy, “United States Presidential Election of 1832,” Encyclopedia Britannica, 2024, accessed November 13, 2024, www.britannica.com/event/United-States-presidential-election-of-1832. ↵

- Harold Whitman Bradley, “Andrew Jackson,” Encyclopedia Britannica, 2024, accessed December 14, 2024, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Andrew-Jackson#ref3613. ↵

- Harold Whitman Bradley, “Andrew Jackson,” Encyclopedia Britannica, 2024, accessed December 14, 2024, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Andrew-Jackson#ref3613. ↵

- Frederic Austin Ogg, The Reign of Andrew Jackson: A Chronicle of the Frontier in Politics (New Haven, Conn: Yale Univ Press, 1920), 184. ↵

- Richard Pallardy, “United States Presidential Election of 1832,” Encyclopedia Britannica, accessed November 13, 2024, www.britannica.com/event/United-States-presidential-election-of-1832. ↵

- Harold Whitman Bradley, “Andrew Jackson,” Encyclopedia Britannica, 2024, accessed December 14, 2024, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Andrew-Jackson#ref3613. ↵

- Paul Kahan, The Bank War: Andrew Jackson, Nicholas Biddle, and the Fight for American Finance (Yardley: Westholme, 2016), 14 ↵

- Frederic Austin Ogg, The Reign of Andrew Jackson: A Chronicle of the Frontier in Politics (New Haven, Conn: Yale Univ Press, 1920), 184. ↵

- Frederic Austin Ogg, The Reign of Andrew Jackson: A Chronicle of the Frontier in Politics (New Haven, Conn: Yale Univ Press, 1920), 185. ↵

- Frederic Austin Ogg, The Reign of Andrew Jackson: A Chronicle of the Frontier in Politics (New Haven, Conn: Yale Univ Press, 1920), 183-184. ↵

- Andrew Jackson, “Avalon Project – President Jackson’s veto message regarding the bank of the United States,” 1832, accessed November 13, 2024, avalon.law.yale.edu/19th_century/ajveto01.asp. ↵

- Frederic Austin Ogg, The Reign of Andrew Jackson: A Chronicle of the Frontier in Politics (New Haven, Conn: Yale Univ Press, 1920), 187. ↵

- Andrew Jackson, “Avalon Project – President Jackson’s veto message regarding the bank of the United States,” 1832, accessed November 13, 2024, avalon.law.yale.edu/19th_century/ajveto01.asp. ↵

- Frederic Austin Ogg, The Reign of Andrew Jackson: A Chronicle of the Frontier in Politics (New Haven, Conn: Yale Univ Press, 1920), 182. ↵

- Samantha Gibson, “The Panic of 1837,” Digital Public Library of America, 2017, accessed November 13, 2024, dp.la/primary-source-sets/the-panic-of-1837 ↵

- Frederic Austin Ogg, The Reign of Andrew Jackson: A Chronicle of the Frontier in Politics (New Haven, Conn: Yale Univ Press, 1920), 190. ↵

- Richard Pallardy, “United States Presidential Election of 1832,” Encyclopedia Britannica, 2024, accessed November 13, 2024, www.britannica.com/event/United-States-presidential-election-of-1832. ↵

- Frederic Austin Ogg, The Reign of Andrew Jackson: A Chronicle of the Frontier in Politics (New Haven, Conn: Yale Univ Press, 1920), 191. ↵

- Richard Pallardy, “United States Presidential Election of 1832,” Encyclopedia Britannica, 2024, accessed November 13, 2024, www.britannica.com/event/United-States-presidential-election-of-1832. ↵

- Harold Whitman Bradley, “Andrew Jackson,” Encyclopedia Britannica, 2024, accessed December 14, 2024, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Andrew-Jackson#ref3613. ↵

- Samantha Gibson, “The Panic of 1837,” Digital Public Library of America, 2017, accessed November 13, 2024, dp.la/primary-source-sets/the-panic-of-1837. ↵

- Samantha Gibson, “The Panic of 1837,” Digital Public Library of America, 2017, accessed November 13, 2024, dp.la/primary-source-sets/the-panic-of-1837. ↵

- Samantha Gibson, “The Panic of 1837,” Digital Public Library of America, 2017, accessed November 13, 2024, dp.la/primary-source-sets/the-panic-of-1837. ↵

- Martin Van Buren, “Documents from M. Van Buren, President of the Bank U. States,” retrieved from the Library Of Congress, 1832, accessed November 13, 2024, 2-3, www.loc.gov/resource/llserialsetce.00339_00_00-083-0098-0000/?st=gallery. ↵

1 comment

Natalia De La Garza

Thank you for this information! It’s very detailed and well-organized, providing a great overview of Andrew Jackson’s background, political life, and military career.