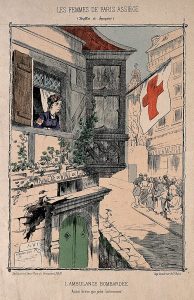

The story begins in 1870, with Clara Barton in Basel, Switzerland on the Swiss-German border at the Red Cross headquarters during the Franco-Prussian War. She had traveled from the United States to Europe to witness the effectiveness of the International Red Cross and its relief efforts during times of war and distress. While in Basel, she used her medical knowledge from serving in the American Civil War to help the relief efforts in the Franco-Prussian War. While she was witnessing the Red Cross’ efforts, she was amazed at how “that little flag” accomplished in four months what she had been unable to accomplish in four years in the American Civil War.1 She was amazed by the efficiency of this organization, and stated, “If I live to return to my country, I will try to make my people understand the Red Cross and that treaty.”2 As she was tending to the wounded soldiers, she realized that a system this effective could have saved even more lives during the American Civil War, and she came to the realization of the need for an American chapter of The Red Cross.

We go back to the beginning where it all started with Clara Barton: working as a clerk in the U.S. Patent Office in 1854 in Washington D.C. It was a confusing time. Clerks had been betraying the secrets of investors and there was a general lack of confidence in the system.3 When she started working in the patent office, she was very skillful and honest in her work, which quickly gained the attention of the commissioner, who eventually gave her the position of confidential secretary. She was the first woman publically employed in a government department.4

In 1861, when the Civil War began and the first wounded soldiers from the Sixth Massachusetts Volunteers started arriving in Washington D.C., Clara’s first thought was, “How can I best serve my country?” And as she aided the soldiers, from that moment on, she consecrated herself to this work as long as the war might last.5 She wanted to help on the frontlines, but women had never been permitted to do so, and it proved rather difficult. But this did not stop her. With determination in her heart, Clara Barton approached a staff member of the Quartermaster Corps, Colonel Daniel Rucker, and pleaded with him to let her go to the front lines. At first, he denied her request, stating that the battlefield was no place for a woman. But to this, she told him that she had a warehouse full of medical items that would aid the cause even more. Moved by her determination, Colonel Rucker not only provided the wagons and drivers to deliver her supplies to the front, but he also obtained the necessary clearances from Washington to allow her to go to the front lines.6 Eventually, after multiple tries, she gained the approval of a commanding officer to go to the frontlines where she quickly found the situation in chaos.7 When she arrived, the system they were using to treat soldiers was in complete disarray, with soldiers being improperly treated and left on the battlefield. She made quick work of this and changed the system to be more effective and life-saving than before. Numerous times, she even went onto the battlefield to bring soldiers back to friendly lines to treat them. She quickly gained a good reputation and the name “Angel of the Battlefield.”

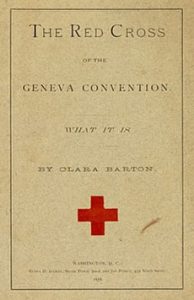

After the war was over and she had made an impact as big as she had, she was exhausted and in need of a break. So she decided to go to Europe to recharge and get back to her normal self. While abroad, she learned about the Geneva Conventions and the International Red Cross and how they were interested in the United States joining the Red Cross. However, because of the Civil War, foreign affairs were the least of the American government’s concerns, and they brushed off the idea. But since the war was over and Clara Barton was learning about the Red Cross, she became interested in the cause and wanted to see its effectiveness. So she decided while in Europe to go to where the International Red Cross was in full force, to the Franco-Prussian War. While in this conflict, Clara Barton recognized its effectiveness. The Red Cross, being less than ten years old, amassed a warehouse of supplies more than that in the Civil War in a fraction of the time.8 She witnessed how they were also able to set up an aid station, where they could work unprovoked and with no mistakes, no needless suffering, no starving, no lack of care, no waste, and no confusion. But they could work with order, plenty, cleanliness, and comfort wherever that little flag made its way.9 She witnessed this effectiveness and how many lives it was saving, and how many more it could have saved if it had been in effect during the American Civil War. She was in awe and filled with determination to bring this cause to the United States. She said, “If I live to return to my country, I will try to make my people understand the Red Cross and that treaty.” She not only made this promise to herself but to the other countries in the treaty of the Red Cross.10 When she returned to the United States in 1873, she was burnt out from years of work and little rest. She had gone to Europe to rest and refresh from serving in the Civil War, only to involve herself in another war. Because of this, she was unable to carry out her promise until 1877, when she presented a letter from President Moynier of the International Red Cross Committee to U.S. President Rutherford B. Hayes, explaining that Mr. Moynier would take the necessary steps to unite the United States to the other countries of the Red Cross. Before doing this, however, she prepared a brochure titled “The Red Cross of the Geneva Convention: What It Is,” which entailed an easy-to-understand overview that could easily be circulated among the general public. It also clarified that it would not be an entangling treaty as commonly believed, and noted that it would provide relief efforts in times of war and peacetime.11

However, it proved nearly impossible to receive any action from this administration, as President Hayes seemed to express little to no interest, and his administration seemed to share a similar feeling. Many people felt that this would violate the Monroe Doctrine by involving the United States in European affairs, and that it would get the United States into entangling treaties. This left Clara wounded and demoralized, but she recognized that she must not be discouraged by this, but still press on.12 It was not until 1881, when the Garfield administration came into power, that she had hopes for the newly elected president to be open to the idea. When she did, President Garfield very much favored the cause and urged his Secretary of State James G. Blaine to consider it, which he did. And when Clara had concerns about the Monroe Doctrine and how it would be read in the Senate, he simply replied: “The Monroe Doctrine was not made to ward off humanity.”13 And with the approval from the President, as well as from the Secretaries of State and War, not a single opposing voice to it was heard in the Senate. They decided to go straight ahead and complete the organization.

Now, there were still certain formalities that needed to be completed before the treaty could be signed and ratified, but they did not let this stop them, and they decided to form it and celebrate anyway. On the 9th of June, 1881, they elected officers. Clara Barton proposed that President Garfield be the President of the American Red Cross, as that was what many other countries did. But Garfield insisted on Clara being the president of the organization, and she won the vote unanimously. All seemed well and nothing could go wrong. Clara had now gotten what she wanted, and the Red Cross was formed. It was supported by the President, his cabinet approved of it, and the people hailed it. All they needed was for the treaty to be signed as a formality. However, on July 2, 1881, President Andrew Garfield was shot and terribly wounded. He fought to survive valiantly, but eventually succumbed to his injuries on the 19th of September that year. The treaty had not been signed, leaving the fate of the American Red Cross in the balance.14

When President Chester A. Arthur took over for the recently deceased President Garfield, he was on board with the American Red Cross in getting it signed and ratified, and so were the Senate and the Secretaries of War and State. But many people, including many in the public, while still approving of the movement, did not see it as a matter of critical importance, and the movement became stagnant for a couple of months. Clara waited anxiously, and many of her attempts to get the movement rolling again seemed to fall flat on their face. After some time, a few members of Congress and a member of President Garfield’s cabinet brought the matter back up in Congress. There was not a single disagreeing voice to the movement. Suddenly, the entire nation switched back to having faith in the Red Cross. However, the people still questioned why they needed an organization whose primary purpose was relief during wartime when they believed the U.S. would never get involved in another war after the Civil War. And still, because of the President’s recent death, the signing and ratifying were delayed. However, there still was a single council in the United States that existed merely under the advice of former President Garfield.

Once again, the Red Cross in the United States found itself hanging in the balance, waiting for something to happen. The Red Cross needed a chance to prove itself and show the people that they were more than just a wartime organization. If only there were a natural disaster that the Red Cross could use as a demonstration of its effectiveness. Almost like clockwork, a fire swept the thumb of Michigan killing hundreds and displacing thousands.15 This was the opportunity they needed to prove themselves, to show the public that the Red Cross was a worthwhile organization. When they arrived, they quickly got to work. Here was where they rallied, and while still young and untried, they got to work. They quickly set up relief rooms stocked with supplies provided by the Relief Committee of Michigan, and the supplies kept coming until they were told no more was needed. The women and men working in the stations took every article of clothing under careful inspection and made them robust and stamped as “Red Cross.” This earned Clara and the Red Cross more recognition and approval from the public, showing them that this organization was important, even when not at war. While there was still no treaty signed, it was certain to follow with full approval from the President and his Cabinet. Despite all of this, Clara was worn out. She had been working alone for years, which took a toll on her, and it slowly worked away at her as she progressed with age. But her dream had been achieved, and with a successful and promising organization, she could slowly step back from the day-to-day tasks, and with time, slowly hand off the torch to the next generation to carry on the cause.

After founding the American chapter of the Red Cross in 1881, Clara Barton went straight into organizing aid efforts for disasters and wartime relief. And they immediately started responding to disasters and emergencies. While Clara Barton ultimately oversaw these operations, she slowly, over the years, began to step back from the day-to-day operations while still being the face of the American Red Cross, traveling around and speaking publicly to younger generations and leaders to slowly take the reins and gain more control. With her health declining more and more, she took on less of the hands-on work and more of the wise advising and guiding of the organization. Because of her efforts, the American Red Cross has responded to countless disasters, saved countless lives, and has, without a doubt, made the world a better place, all because of Clara Barton’s efforts.

- William Eleazar Barton, The life of Clara Barton: Founder of the American Red Cross Vol. 2 (Boston, Mass, Boston u.a.: Harvard Univ. Libr. Delivery Service Mifflin, 1922), 12. ↵

- William Eleazar Barton, The life of Clara Barton: Founder of the American Red Cross Vol. 2 (Boston, Mass, Boston u.a.: Harvard Univ. Libr. Delivery Service Mifflin, 1922), 12. ↵

- William Eleazar Barton, The life of Clara Barton: Founder of the American Red Cross Vol. 1 (Boston, Mass, Boston u.a.: Harvard Univ. Libr. Delivery Service Mifflin, 1922), 89-90. ↵

- David H Burton, Clara Barton: In the Service of Humanity (Westport, Conn: Greenwood Press, 1995), 19. ↵

- Ida Husted Harper, “The Life and Work of Clara Barton,” The North American Review 195, no. 678 (1912): 702. ↵

- David H Burton, Clara Barton: In the Service of Humanity (Westport, Conn: Greenwood Press, 1995), 33-34. ↵

- Ida Husted Harper, “The Life and Work of Clara Barton,” The North American Review 195, no. 678 (1912): 701. ↵

- David H Burton, Clara Barton: In the Service of Humanity (Westport, Conn: Greenwood Press, 1995), 65. ↵

- William Eleazar Barton, The life of Clara Barton: Founder of the American Red Cross Vol. 2 (Boston, Mass, Boston u.a.: Harvard Univ. Libr. Delivery Service Mifflin, 1922), 10-13. ↵

- William Eleazar Barton, The life of Clara Barton: Founder of the American Red Cross Vol. 2 (Boston, Mass, Boston u.a.: Harvard Univ. Libr. Delivery Service Mifflin, 1922), 10-13. ↵

- David H Burton, Clara Barton: In the Service of Humanity (Westport, Conn: Greenwood Press, 1995), 81-87. ↵

- David H Burton, Clara Barton: In the Service of Humanity (Westport, Conn: Greenwood Press, 1995), 87-90. ↵

- William Eleazar Barton, The life of Clara Barton: Founder of the American Red Cross Vol. 2 (Boston, Mass, Boston u.a.: Harvard Univ. Libr. Delivery Service Mifflin, 1922), 150. ↵

- William Eleazar Barton, The life of Clara Barton: Founder of the American Red Cross Vol. 2 (Boston, Mass, Boston u.a.: Harvard Univ. Libr. Delivery Service Mifflin, 1922), 158-160. ↵

- William Eleazar Barton, The life of Clara Barton: Founder of the American Red Cross Vol. 2 (Boston, Mass, Boston u.a.: Harvard Univ. Libr. Delivery Service Mifflin, 1922), 169-171. ↵

1 comment

Natalia De La Garza

Thank you so much for this detailed and engaging account! I truly loved the information you shared about Clara Barton and the origins of the American Red Cross. It was fascinating to learn about her determination, impact, and the inspiration she drew from the International Red Cross. Great work!