With the death of Huayna Capac in 1527 due to a mysterious disease known today as smallpox, the Inca Empire faced an unprecedented and rampant fight between the two sons of the Sapa Inca: Huáscar and Atahualpa. When Huáscar, the twelfth emperor of the Incas, heard the news of Huayna Capac’s death, he knew it was his time to take over the throne. Little did he know his half-brother, Atahualpa, would challenge him for his newly obtained throne, leading to a civil war between these two factions of Inca claimants.1

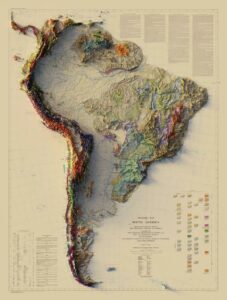

In just under a century, the Inca civilization occupied almost all of the west coast of South America. This region is known as Tahuantinsuyo, or “Realm of the Four Parts.” Spanning from modern-day countries of Ecuador, Peru, Chile, and Argentina, the Inca leaders instilled in their subjects an expansionist mindset.2 Leaders such as Pachacútec, known for founding the site of Machu Picchu, and Capac Yupanqui are to be given credit for why the Inca territory grew to be so large.3

After the rulers Tupac Inca Yupanqui, the ninth Sapa Inca, and Pachacútec, the tenth Sapa Inca, the power and leadership role landed in the hands of Huayna Capac, who was known to be a strong and intelligent master of war. During his time as the eleventh Sapa Inca (1493–1527), he continued the custom of going on expeditions with soldiers of his choosing. All Inca rulers and leaders did this to fulfill one of their goals, which was the expansion of their realm to become more powerful.4

Huayna Capac left Cusco on one of these expeditions, leaving his native land and the heart of Tahuantinsuyo, while also leaving behind his wife and son Huáscar. He did not know at the time, but his expedition set in Quito, north of Cusco, would be approximately thirty years long. Living a new life, dealing with new stresses, and encountering new enemies, Huayna Capac began a family with one of his mistresses. She too brought him a son. His name was Atahualpa and he was raised in Quito by the Sapa Inca himself. Weapons, tactics, conflict, and ruthlessness became part of Atahualpa’s everyday life and habits. Whenever Huayna Capac could not look after his son, he asked his generals to take care of him, specifically telling them to treat him as one of their soldiers. Atahualpa was taught the art of war by his father and was treated as a soldier by all the generals on the expedition. Thanks to this, his growing years led him to become a strong and brave warrior, ready to take on anything and anyone standing in his way.5

In Cusco, Huáscar was raised by Huayna Capac’s wife, Ragua Ocllo. She was also the Sapa Inca’s “sister and daughter of the Inca Topa Inca Yupanqui.” This son grew up surrounded by women, given that the father was away for thirty years. The difference was profound: Huáscar’s temperament, characteristics, and personality, in comparison to Atahualpa, were undoubtedly different.6

After many years, in 1527, both young men experienced the death of their father alongside their eldest brother. Their deaths were due to the European-brought disease, smallpox. Huáscar, now the twelfth emperor of the Inca Empire, knew that he would inherit his father’s position. This was because years before Huayna Capac’s death, he chose his line of heirs. The Sapa Incas were so powerful that they could choose anyone to replace them, but it had become a tradition to choose the eldest son. The list named Ninan Kuyuchi as the first inheritor and Huáscar as the second, if anything were to occur. Atahualpa, now in the position of the thirteenth emperor of the Inca Empire, never agreed to this list. He believed that the next Inca ruler should be one who knew the ins and outs of war and negotiation, as well as someone who had prior experience. To Atahualpa, the tradition did not matter, and he argued that it should be him at the top of the list.7

A few days after the reported deaths, a new Sapa Inca was declared. Huáscar was now the new Inca ruler, making him the twelfth Sapa Inca. One of his first duties as the new leader of Tahuantinsuyu was to organize a “celebration,” or a ceremony honoring both Huayna Capac and Ninan Kuyuchi. Upon finishing the final details of the upcoming event, Huáscar ordered both Atahualpa and members of his embassy to attend the ceremony. When Atahualpa heard of this order, he simply dismissed it and chose to stay behind to look after the “Quito district.” Although he chose not to attend, Atahualpa sent gifts to show that he was still present. This act infuriated Huáscar, as he believed that it was a son’s duty to honor his father. This caused Huáscar to send his soldiers out to murder all the members of Atahualpa’s embassy. Atahualpa’s reaction was largely due to his point of view regarding the line of heirs; he and his army chose to rebel against the new authority that was his brother. This marked the beginning of the Inca Civil War, as the new Sapa Inca declared war on his brother.8

“Huáscar executed everyone he found in Cuzco who was connected with his brother.” The first official battle took place in 1529, named the Battle of Quipaipan. This battle was significant as it set the tone for the rest of the war. Atahualpa’s general, Quisquis, played a crucial role in obtaining the victory. The number of casualties that pertained to the Atahualpan military was significantly lower compared to the number of deaths under Huáscar’s military guidance. The battle that followed was the Battle of Chimborazo. This took place on “a prominent volcano located in present-day Ecuador.” Huáscar’s military and supporters gave it their all, but it was not enough for Atahualpa’s military experience in the field. Huáscar lost yet again. This time, he and his supporters saw the great power Atahualpa’s men contained. The sense of victory Atahualpa and his men felt transferred into the next two battles: the Battle of Riobamba and the Battle of Cajamarca. Riobamba was fought on Ecuadorian soil and led to Huáscar’s third loss in the Incan Civil War. Finally, the Battle of Cajamarca can arguably be seen as the last part of this civil war. Huáscar lost the final battle, leading to him losing his position of power. The Inca civilization had a new ruler, Atahualpa, who became the thirteenth Sapa Inca.9

The end of the Civil War did not officially come until the Battle of Cajamarca. Huáscar lost all the battles because of his lack of understanding in the art of war. This is what ultimately led him to be dethroned. Atahualpa got what he always desired: a shot at being a ruler. In 1532, when he finally defeated and captured his brother, he was officially declared the new Sapa Inca, the thirteenth Sapa Inca. He was going to change and expand Tahuantinsuyo. He was going to reform the Inca civilization, and most importantly, he was going to celebrate. Although he did get an opportunity to celebrate, less than a month into his new position, his projects were postponed due to the arrival of abnormal-looking men. Atahualpa and his people described the men who arrived on ships as “Gods or supernatural beings” because of their characteristics, such as their beards and light skin complexion. They were the Spanish Conquistadors under the leadership of Francisco Pizarro.10

On November 16, 1532, Atahualpa was invited to a dinner that was set up by the Spanish as a way of initiating an alliance. After many hours, the thirteenth Sapa Inca finally chose to attend this event. When he arrived with his military, the Spanish greeted him with friendly eyes. Atahualpa walked into the dining room and saw the variety of new and distinct foods. They stood up and all drank the wine. Atahualpa insisted that everyone sit and eat. The men did just that, and as soon as Atahualpa was seen truly invested in the presence of the Spanish and their cuisine, Francisco Pizzaro’s men jumped up and attacked Atahualpa, capturing him and holding him from the back, placing a knife on his neck in case he tried to resist. This was the end of the Inca civilization. In the hands of Francisco Pizarro lay the “Realm of Four Parts.”

From the prison where the Spanish held him captive, Atahualpa ordered his army to execute his brother, in case he regained power and became the Sapa Inca once again. He remained alive only because, when he was first captured, Atahualpa stated that he could fill a whole room with gold. He explained that for his freedom, he would act as a vessel, providing the newly arrived conquistadors with gold. They agreed, but there was one caveat: he would keep his life, but only if he accepted to be under Spanish custody and supply Pizzaro’s expeditioners with gold. Afraid of losing his life, the former Sapa Inca agreed. He was able to buy himself time, having the opportunity to call for his army through letters. A Spanish prison official heard about the Peruvian prisoner asking his army to come and free him. A year after the ceremony that crowned him and made him Sapa Inca, on July 26, 1533, the Spanish executed Atahualpa. This left the Incas without a ruler, a guide, or a purpose. They only had foreigners who were hungry to take over everything. This thirst for power led to the end of the Incas.11

This story between the brawling brothers shows how a powerful civilization came to an end in less than a century. Having the ability to become even larger and stronger, internal conflicts and struggles within their government, as well as within their family, caused them to lose sight of their purpose: to protect their people and their land. The way in which the Spaniards arrived as soon as the Inca’s civil war culminated may have been coincidental. This could have been the reason the Spanish conquistadors took over the region with ease and little resistance. The Inca people were vulnerable and could not fight to protect their people and land. This occurred to the ancestors of Peruvian people over five centuries ago, but in contemporary times we see some of the same struggles: modern-day Atahualpas and Huascars fighting for their interests and not those of the community. Furthermore, we also have modern-day conquistadors who want to tear the country apart for their own gain.12 One example of these struggles includes foreign companies such as Odebrecht coming in and making deals with corrupt politicians. In addition, the fact that Peru has had six presidents in the last five years and an overwhelming amount of allegations against politicians for being corrupt shows us a few of the hardships faced. Peru has the ability to become a first-world country, as powerful as Canada and the United States of America, but among other facts and historical events, these patterns and habits—the ones that ended the Inca Civilization—restrain Peru from fully developing its potential.

- Brian S. Bauer, “Review of The Last Days of the Incas, by Kim MacQuarrie,” The Historian 72, no. 1 (2010): 200–201. ↵

- María Rostworowski, Historia Del Tahuantinsuyu, 3rd ed. (Lima: IEP Ediciones, 2017), 68-73. ↵

- Maria Rostworowski, Historia Del Tahuantinsuyu (Lima: IEP Ediciones, 2017), 105-111. ↵

- María Rostworowski de Diez Canseco, History of the Inca Realm (Cambridge, UK; New York: Cambridge University Press, 1999), 136-142. ↵

- Gary Urton and Adrianna Von Hagen, “King List,” Encyclopedia of the Incas, 2015, (Lanham, MD: Roman & Littlefield Publishers). ↵

- William Hickling Prescott, History of the Conquest of Peru (New York: Heritage Press, 1957), 165-173. ↵

- Paul E. Kuhl, “Huáscar and Atahualpa Share Inca Rule,” Salem Press Encyclopedia, 2022. ↵

- Rebecca M. Seaman, “Inca-Spanish War Timeline,” Conflict in the Early Americas: An Encyclopedia of the Spanish Empire’s Aztec, Incan, and Mayan Conquests, 2013, (ABC-CLIO, 183). ↵

- Edward Hyams, The Last of the Incas : The Rise and Fall of an American Empire (New York : Simon and Schuster, 1963), 151-166. ↵

- David M. Jones, “Discovering the Incas,” The Illustrated Encyclopedia of the Inca Empire: A Comprehensive Encyclopedia of the Incas and Other Ancient People of South America with More than 1000 Photographs, 2012, (Leicestershire, England: Hermes House). ↵

- Philip Ainsworth Means and Jay I. Kislak, Fall of the Inca Empire and the Spanish Rule in Peru; 1530-1780 (New York, London: C. Scribner’s Sons, 1932), 42-44. ↵

- Gustavo Pons Muzzo, Historia del Perú: Emancipación y República (1961), 256-265. ↵

10 comments

Johnny Marin Cedeno

Gonzalo, as a Peruvian myself I greatly appreciate your article. I am proud to see your passion and desire in providing many people around the nation to learn about the Peruvian history. Thank you. From New Hampshire.

Patricia Johanson Akin

Gonzalo: Your article is very well written. It’s a very interesting story that I had forgotten. Your research seems very thorough. You should expand your articles focused on the history of corruption in Peru. Muchos éxitos Gonzalito!

Andrew Ramon

Gonzalo, this was a very interesting read and introduced me to a story that I haven’t seen before. I also like how you apply it to our modern era to show that history repeats itself. I would like to read more of your articles in the future, because you tell a great story.

Andrea Realyvasquez

This article was such a great read! I enjoyed learning about Peru’s history and the struggles that the country has faced since the times of the conquistadores. Implementing the big idea picture that if the rulers of Peru had just set aside their differences to protect their land and people, the Inca civilization wouldn’t have been destroyed so easily. This ideal is so important in modern-day conflicts because of how important it is to not lose our sense of purpose.

Eduardo Saucedo Moreno

Hello Gonzalo! great work with your article! It was really interesting to learn about Atahualpa and Huáscar. I had never heard of them but this definitely helped me and educated me with understanding who they are. I liked how you told their stories in a very simple way without getting off-track. It’s sometimes common for someone to over-explain historical figures like them. Good job!

Jose Cornejo

Gonzalo, I have to say it is very well written, and as a Peruvian, I greatly appreciate that you explain the history of the Incas in such a great narrative!!

Kennedy

Gonzalo, that was an Amazing article showcasing history so rich to Peru and the world for those who appreciate history. Keep up the great work and success to you in your life pursuits thank you again for the artilcle!

Oscar Rodriguez

Gonzalo, I want to congratulate you for the wonderful thing you wrote, you are a profile of a great professional.

Ricardo Izquierdo

Excellent article that helps us to understand the end of a millennia-old stage. Congratulations. Well done!

Rocio Mori

Hello Gonzalo. I want to say that this article is very interesting and very professional. I adore read all about. Taking us to a trip to the Incas Impaired. I can’t be more proud of you son.