By the time Franklin reunited with his son in Pennsylvania, he had already been writing to him about the possibility of independence. Franklin’s son, William, was the governor of the royal colony of New Jersey. Franklin wanted his son to join him in the movement for independence, but William resisted his attempts and stayed loyal to the king. Franklin made his views more explicit when he, William, William’s son Temple, and Franklin’s friend Joseph Galloway, met in Trevose, a town outside Philadelphia, on May 15, 1775. Franklin and Galloway got into an argument about the situation in the colonies, and William suggested they stay neutral. Franklin openly declared that he supported independence and began talking about the corruption of the kingdom. This would be one of the last times Franklin would ever see his son.1

Past this point, Franklin’s stance on independence would be solidified by unfolding events, such as the burning of Charleston and the Battle of Bunker Hill. Franklin’s wish for colonies to become an independent nation, however, was not due only to his frustration with the crown’s abuses, but also due to his vision of the future of America. Franklin didn’t want America to be a land where people’s status in life would be determined by birth and traditional social structures. Franklin saw a future America as a nation of proud people holding private provinces, such as shopkeepers, tradesmen, merchants, and artisans. He made these ideas clear in letters to his son, but William still stayed loyal to the king.2

Franklin became more enthusiastic about this, and on July 21, he sent his “Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union” plan to Congress. Realizing that this would basically be a declaration of independence, he decided only to submit it to Congress, and not to have a vote on it. Still, this plan is evidence of his vision of an independent nation. His plan proposed that America be called “The United Colonies of North America.”3

Franklin was still open to any possible resolution with the Crown, though. His plan said the union would be dissolved if the King accepted America’s demands. Furthermore, two months after the United States actually declared independence, Franklin and two other diplomats met with Lord Howe, the commander of all British troops in America. They were to discuss some kind of plan for America to govern itself, but still remain part of Great Britain. The meeting, however, didn’t get anywhere.4

As we know, though, there was no peaceful resolution, and the journey toward independence continued. Congress needed the United States to be recognized by other European countries, and to find an ally, and the obvious candidate was England’s enemy France. Congress predicted that France, understandably, would be hesitant to support the United States. France had just lost a war against Britain only thirteen years before, and up to that point, the Continental Army hadn’t been very successful. Congress needed to send a diplomat to France to convince them that America would be a worthy investment. It needed someone enthusiastic in his resolve, but discreet in his actions. The perfect option was Benjamin Franklin. Besides being a tactful diplomat, Franklin was also extremely popular in France due to his scientific inventions. The French may not have known much about America, but everyone knew about Franklin. Congress also chose Silas Deane, a congressional delegate from Connecticut, and Arthur Lee, the colonial agent in London, to go with Franklin.5

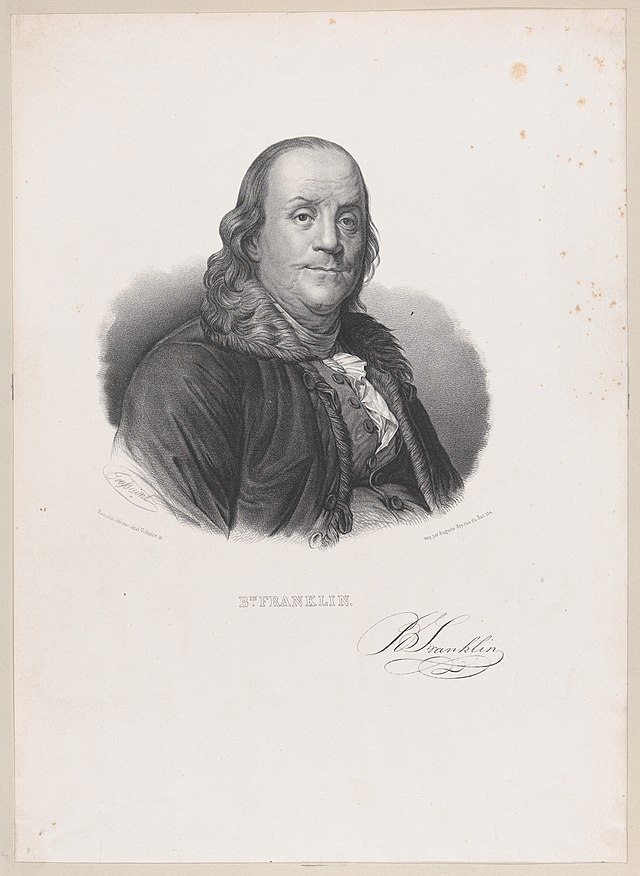

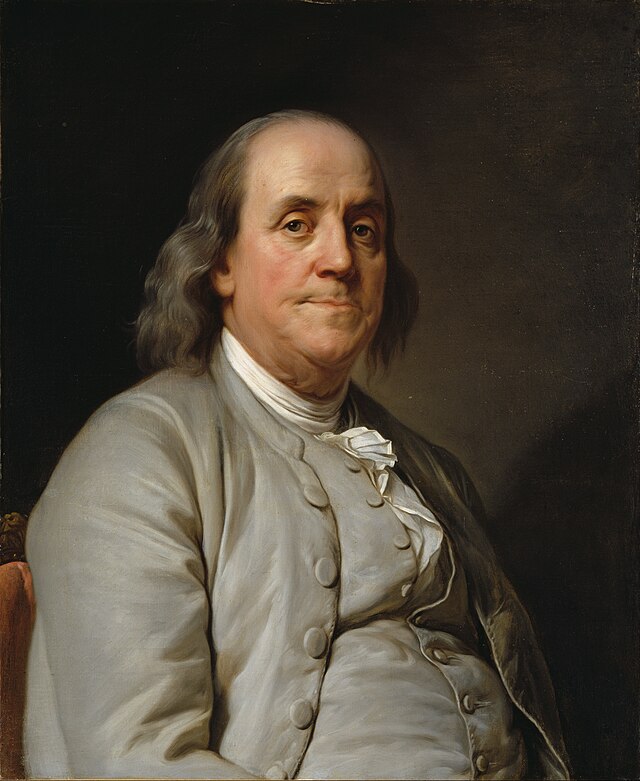

Franklin arrived in France as a celebrity. They quickly put together a ball to throw for him, and when he entered Paris, people were lined up on the streets just to see him. He chose to wear a simple fur cap instead of the wig that most people wore. Subsequently, many women began wearing wigs that imitated his hat. Portraits, medallions, and other small trinkets were being made with Franklin’s face on it. The personal assistant for Princess Élisabeth talked about Franklin so much, that the King gave her a toilet with Franklin’s face on it.6

Franklin settled in Passy, a village on the outskirts of Paris. He met Jacques-Donatien Leray de Chaumont, who owned an estate where he offered rooms for Franklin to stay in. Arthur Lee also arrived in Passy. Lee was an extremely paranoid person; he believed everyone in Passy was either a spy or trying to steal money. He often accused people of being either disloyal or unscrupulous. The only reason Congress still trusted him was because sometimes he coincidentally ended up being right. For example, he got a good reputation when he exposed Silas Deane for questionable banking transactions. Lee was also jealous of Franklin. He used the good reputation he got from exposing Deane as leverage to create rumors about Franklin.7 Franklin said that: “in sowing Suspicion and Jealousies, in creating Misunderstandings and Quarrels among Friends, in Malice, Subtility and indefatigable Industry, he has I think no Equal.” In Franklin’s later years in France, Lee and his brothers would go on to cause more and more trouble for Franklin.8

Arthur Lee was not the only one who would cause problems for Franklin. Edward Bancroft, the secretary of the American delegation, was spying for Britain. Lee was extremely suspicious of Bancroft, but, of course, the other delegates didn’t take him seriously. Ironically, Lee did not know that his own secretary was a spy too. Franklin never ended up finding out that Bancroft was a spy; however, he did know that there were spies around him, and later he would end up playing them against each other.9

A few days after he arrived in Paris, Franklin, with Lee and Deane, met with the French foreign minister, the Comte de Vergennes. Franklin immediately tried to make an alliance with France, but it basically didn’t get anywhere. Franklin realized that he could not just come to France and immediately demand an alliance. He had to convince France, and the French people, to believe in the American cause. Franklin had his printer set up in Passy and began publishing American documents translated into French.10

Franklin became extremely popular by writing satires and anonymous letters. There was a British ambassador, Lord Stormont, who published propaganda reports. One time, someone asked Franklin what he thought about one of Stormont’s reports, and Franklin said, “It is not a truth, it is only a Stormont.” After that, Paris began using the word “Stormonter,” playing on Stormont’s name and the French verb “mentir,” meaning “to lie.” 11 Franklin also became famous for his fake letter, “An Edict by the King of Prussia.” Britain used Hessian soldiers to fight the Americans, but only agreed to pay Prussia for any soldiers that died, not any that were wounded. The letter was written to seem as if it were coming from a count in Prussia, encouraging the Hessian commander to make sure as many Hessian soldiers die as possible so Prussia could make as much money as possible.12

Franklin’s actions confused Foreign Minister Vergennes. He didn’t understand why Franklin would come to France, propose an alliance, and then retreat to his house just to publish satires. He was not the only one puzzled by Franklin. People began spreading rumors; the New Jersey Gazette said that Franklin was creating an electrical device to shift landmasses. Franklin wasn’t doing anything like that, but people were still mesmerized by him. Every day, there were people sending Franklin letters asking for advice, or people were showing up at his house with questions.13

In September 1777, Franklin decided to request Vergennes for French recognition of the United States again. However, shortly after their meeting, news came that the British General Howe had taken over Philadelphia, Franklin’s hometown. This was not looking good for Franklin; he not only had requested from Vergennes seven times more aid than what France had already secretly given, but also by untimely coincidence, happened to ask right before a big loss for the United States. If General Burgoyne’s army met with General Howe’s army, the northeastern part of America would be cut off from the rest. Franklin, though, played it cool and pretended that he was not bothered by the current situation. Franklin said that Howe’s capture of Philadelphia was actually a mistake by Howe, and that it slowed him down. Franklin suggested that if Howe took too long to go north and meet with Burgoyne, they might stay separated from each other.14

Lee wanted to use America’s bad situation as an opportunity to force the French to help. He suggested that they ought to warn France to support the United States now, or else Britain will win. Most other American diplomats also wanted to be tough on other countries when asking for help. They often made demands, and had the attitude that other countries should help the U.S. Franklin understood that the United States had to seduce France, and show them why it would be beneficial to help the U.S. This is why Franklin had more success than any of the other diplomats.15

What is almost unbelievable, is that only three months later, in December, Franklin’s exact prediction came true. News arrived that Howe was not able to meet with Burgoyne. Burgoyne, isolated, had to surrender his army at the battle of Saratoga. Franklin wrote the news to Vergennes, and two days later, King Louis invited the Americans to resubmit the alliance request. On December 7, Franklin met with Vergennes, and France agreed to a recognition of the United States, and other treaties. However, France had an agreement that it would not make any treaties without the approval of Spain, so Vergennes sent a letter to Madrid. The letter came back a few weeks later, and what is strange is that for some reason, the King of Spain rejected the alliance. France was now in a stressful spot, unsure whether or not to make the alliance without Spain’s permission.16

A bit before this happened, Britain sent their spymaster, Paul Wentworth, to meet with Deane to try to make a peace deal. Franklin, understanding that there were spies all around him, and that France and Spain were both desperate, decided to play the spies against each other. Franklin pretended that he was unaware of the British spies and allowed them to find out how close he was to a deal with France. He knew this would put more pressure on Wentworth to meet with him, which is what he did on January 6. He let French spies listen to everything he said to Wentworth, and this pressured Vergennes to recognize the U.S. as soon as possible. Vergennes asked Franklin what was necessary so that the American delegation would not communicate with Britain. Franklin said that France needed to accept the treaties.[16. Walter Isaacson, Benjamin Franklin: An American Life (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2003), 345-346.]

Ignoring Spain, King Louis accepted two treaties with the United States: one trade agreement, and one military alliance. On February 5, 1783, the American commissioners signed the treaty, and on the 20th of March, they met the King in Versailles. There were crowds outside the palace saying “Vive Franklin!” The other American delegates were wearing the ceremonial swords and other items that were required to enter the palace. Franklin, however, simply wore a plain brown suit. When Franklin went to King Louis’s bedroom, King Louis was in a prayer position and said, “I hope that this will be for the good of both nations. I am very satisfied with your conduct since you arrived in my kingdom.” The French support Franklin got is what won America independence. Franklin achieved his vision of a country where what someone can become is not determined by birth. While at Versailles, Queen Marie-Antoinette was dismissive of Franklin, saying that “a printer’s foreman” wouldn’t have been able to rise so high in Europe. With that one statement, Franklin’s motivation is evident.17

- Walter Isaacson, Benjamin Franklin: An American Life (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2003), 293-294. ↵

- Walter Isaacson, Benjamin Franklin: An American Life (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2003), 295. ↵

- Walter Isaacson, Benjamin Franklin: An American Life (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2003), 299 ↵

- Walter Isaacson, Benjamin Franklin: An American Life (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2003), 300, 318-320. ↵

- Walter Isaacson, Benjamin Franklin: An American Life (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2003), 320-321. ↵

- Walter Isaacson, Benjamin Franklin: An American Life (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2003), 325, 327. ↵

- Walter Isaacson, Benjamin Franklin: An American Life (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2003), 331. ↵

- Edmund S. Morgan, Benjamin Franklin (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2002), 256-257. ↵

- Walter Isaacson, Benjamin Franklin: An American Life (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2003), 333-336. ↵

- Walter Isaacson, Benjamin Franklin: An American Life (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2003), 337-339. ↵

- Walter Isaacson, Benjamin Franklin: An American Life (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2003), 340. ↵

- Walter Isaacson, A Benjamin Franklin Reader (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2005), 270. ↵

- Walter Isaacson, Benjamin Franklin: An American Life (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2003), 340-342. ↵

- Walter Isaacson, Benjamin Franklin: An American Life (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2003), 342. ↵

- Walter Isaacson, Benjamin Franklin: An American Life (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2003), 342. ↵

- Walter Isaacson, Benjamin Franklin: An American Life (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2003), 345. ↵

- Walter Isaacson, Benjamin Franklin: An American Life (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2003), 346-349. ↵

3 comments

Jordan Robbins

Hi, through your writing, I learned more about Benjamin. I mainly know Benjamin Franklin from primary school and Hamilton, LOL. But I like how you explained his story and leadership for the French. Where’d you get the photo of him? I’ve never seen a photo so clear of him!

Alysia Cano

This article paints a vivid portrait of Franklin’s diplomacy in France, showing not only his political acumen but also his personal struggle with his son and the complexities of international negotiations. Franklin’s charm, strategic thinking, and ability to navigate a web of spies, political intrigue, and personal rivalries played a crucial role in securing French support for America’s independence.

Danielle Villanueva

I thoroughly enjoyed learning about Benjamin Franklin’s diplomatic mission to France during the American Revolution. This article revealed how Franklin used his charm, wit, and strategic thinking to win French support for American independence. It was fascinating to see how he turned his scientific fame and clever satire into a diplomatic advantage. I would have loved to know more about the specific strategies he used to win over the French public.