In the blistering heat of Delano, California, Latino migrants worked for hours on end picking grapes for low pay and in awful conditions. In the age of social justice movements, one man established labor laws for workers. Having been a child of migrant workers and having worked in the field himself, Cesar Chavez saw the mistreatment of field workers in the U.S. and decided to take a stand. From 1965 to the summer of 1970, Chavez and his team of Delores Huerta and the United Field Workers boycotted large corporations and held grassroots meetings to fight for better treatment and rights for migrant field workers not just in California but throughout the United States.

Chavez, having experienced his own hardships in the fields and its impact on his family, was sympathetic with migrant workers across California. He understood that the low wages and harsh conditions were not suitable long term in the U.S., and it only fueled his anger to fight for better working laws. No one else was fighting for labor rights and Chavez knew if he did not take a stand, then who would?1

A pivotal moment for Chavez came when he partnered with the newly formed United Field Workers (UFW) labor group as well as with Delores Huerta and her army of angry laborers in 1965. With the UFW and Huerta, Chavez was able to organize boycotts, established picket lines, and grassroots meetings in Delano.2

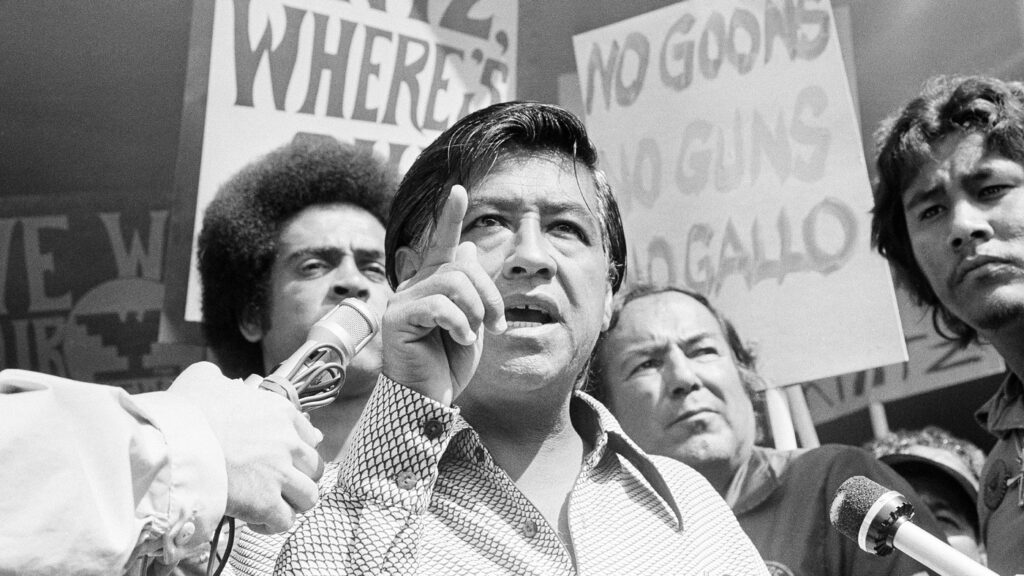

The UFW, Chavez, and Huerta’s biggest movement was the mobilization of migrant workers to boycott grape growers in Delano until better pay was given to workers. They started with small meetings, marches, and newspaper ads, eventually moving on to large-scale boycotts. At these meetings, farmworkers and allies united with Chavez and the UFC to listen, learn, and organize. Chavez, a strong voice and commanding presence, stood by the side of Huerta, an eloquent speaker with passion that inspired many. These grassroots gatherings served as a classroom for social change. Those who attended these meetings became enlightened about what the pain and suffering migrant workers felt on a day-to-day basis. The back-breaking labor and low wages came to light to those who were in the dark about California’s agricultural landscape. Testimonies and stories of the pain in the fields made US people angry at large corporations and their treatment of migrants.3

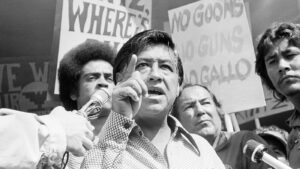

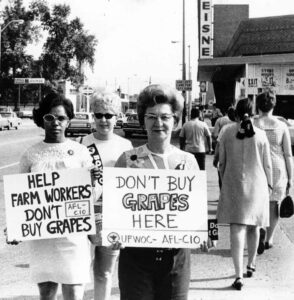

The newspaper and radio became a main channel to showcase Chavez’s movement. It amplified the message the UFW was promoting. Chavez and Huerta saw how the press impacted society and used it to their advantage by telling the heart-breaking stories of those working in the field. The movement strategically used the papers to publish articles that exposed the exploitation of migrant workers and encouraged consumers to boycott fruit, mainly grape, growers in not just California but the US as a whole. Through rallies, newspapers, and boycotts, it showed consumers in the US the pain and strife that farm workers faced in order for people to have fruit on their dining room tables. The movement spread not just to Chicano workers but to Filipino workers as well. The issue of unfair labor laws was impacting multiple minority groups in California. The large-scale boycott lasted years, from 1965 to 1970, and gained national recognition, and was a turning point in labor rights all around the country. It was not just migrant workers boycotting but everyday people were not buying wine and grapes from Delano growers. The rallying support grew to national levels and inspired other labor movements across the nation. 3

The newspaper and press work were bringing about change, but more had to be done. Then, the picket lines emerged. Leaflets and posters were distributed, and stores were boycotted and canvassed. These boycotts were strategic movements to put pressure on grape growers to change how they treated migrant workers. Field workers, their allies, and the community would picket outside packing facilities and stores that sold fruit grown by migrants. The picket lines served multiple purposes. It was a visible act of resistance, but it was nonviolent, which amplified the peaceful nature of Chavez, the UFW, and Huerta. By strategically holding marches and boycott picket lines at stores and fields, it forced growers and large corporations to confront the demands of migrant workers head-on.2

Chavez, a prominent figure in the history of labor rights, found inspiration from a multitude of people. Inspired by Gandhi, Chavez believed in nonviolent protests. He studied their philosophies of change and nonviolent resistance, truly emphasizing how boycotting can cause more change than violent outbursts. Chavez was right. Through his collective actions and group efforts, the labor rights for workers improved and people felt inspired to join the fight for the rights of migrants in America. Though it took five years, Chavez and his movement changed the labor laws for many migrants not just in California but elsewhere in the US and for future generations. Not only inspired by Gandhi but by other social justice movements at the time such as the ones held by Martin Luther King Jr., Chavez saw how impactful it was to have a non-violent protest approach and implemented those into his own movement.1

The tension between workers and grape farm owners grew when the large corporations started facing large economic losses. Finally, in the summer of 1969, Chavez and his army had reached a large enough audience where everyday table grapes were not being bought and now the employers would finally listen to their demands. The grape growers in Delano agreed to meet with Chavez and the UFW. The five-year struggle led by Chavez was finally coming to fruition.7

Grape growers finally agreed to meet with Chavez and the UFW, to listen and meet the demands of laborers. Through painstakingly slow negotiations, they finally reached the Grape Agreement of 1970, which outlined wage increases, better working conditions, and access to healthcare. It was a pivotal moment for migrant workers all across the US. Chavez finally achieved better working conditions for migrant workers and better pay, which would leave a lasting legacy on labor movements in the United States. Chavez, Huerta, and an army of angry consumers and workers demonstrated the power of coming together to fight for social justice. They laid the foundation for future labor movements on how to successfully and peacefully fight for better treatment.8

- Roger Bruns, Encyclopedia of Cesar Chavez: The Farm Workers’ Fight for Rights and Justice, Movements of the American Mosaic (Santa Barbara: Greenwood, 2013). ↵

- Matt Garcia, “A Moveable Feast: The UFW Grape Boycott and Farm Worker Justice,” International Labor and Working-Class History, no. 83 (2013): 146–53. ↵

- Jack Angell, “The Grape Boycott,” Journal of ASFMRA 34, no. 1 (1970): 67–70. ↵

- Jack Angell, “The Grape Boycott,” Journal of ASFMRA 34, no. 1 (1970): 67–70. ↵

- Matt Garcia, “A Moveable Feast: The UFW Grape Boycott and Farm Worker Justice,” International Labor and Working-Class History, no. 83 (2013): 146–53. ↵

- Roger Bruns, Encyclopedia of Cesar Chavez: The Farm Workers’ Fight for Rights and Justice, Movements of the American Mosaic (Santa Barbara: Greenwood, 2013). ↵

- CESAR CHAVEZ, “The California Farm Workers’ Struggle,” The Black Scholar 7, no. 9 (1976): 16–19. ↵

- Andrew Jacobs, “Friends and Foes: Religious Publications and the Delano Grape Strike and Boycott (1965-1970),” American Catholic Studies 124, no. 1 (2013): 23–42. ↵