The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), signed in 1966 as part of an initiative to standardize the extent of natural human rights across the globe, provides in §§ 1-2 of its 19th article:

1. Everyone shall have the right to hold opinions without interference.

2. Everyone shall have the right to freedom of expression; this right shall include freedom to seek, receive and impart information and ideas of all kinds, regardless of frontiers, either orally, in writing or in print, in the form of art, or through any other media of his choice.1

Although the degree to which every country that signed this document binds themselves to these clauses in reality is questionable, examining how different countries handled the freedom of expression preceding the ICCPR is worthwhile. Not only does it explain our current state of rights recognition, but it also allows us to better appreciate our being granted these freedoms by our contemporaries. This article will examine the freedom of expression as it pertains to the art of music; it will highlight a number of classical music composers whose music was censored or banned in certain countries during times of international conflict. These composers were each pivotal figures in the evolution of the Common-Practice period tradition. However, whether due to held political opinions, ethnicity, or religion, they were deemed intellectual and artistic threats to national security in the respective countries where their works had been banned.

*Works hereinafter marked with an asterisk can be listened to, along with other suggested works, in the “Suggested Works” list at the bottom of the article.

Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy

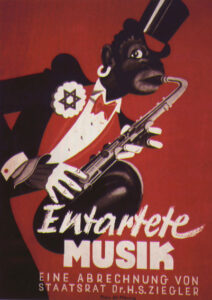

Nazi Germany provides the most infamous example of national music censorship established prior to World War II. The state of Germany sought to repudiate the influence of works from anyone with Jewish ancestry, a group to whom Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy belonged.

The general public might recognize Mendelssohn for his brilliant melodic material. (See the Violin Concerto* and A Midsummer Night’s Dream*.) But Mendelssohn’s achievements far exceeded a knack for melody. He pioneered new chamber music instrumentations2; his tenure as a conductor allowed him to program the music of Johann Sebastian Bach, partially reviving it from almost total obsolescence3; his incorporation of developmental practices characteristic of late Beethoven diffused across music so as to become part of the general Romantic style.4

But notwithstanding all that Mendelssohn provided for music (and the fact that this influence had exhibited itself for the greater part of the past century), the Nazis perceived him only as a Jew. It was of no significance that Mendelssohn was a Christian convert—this was clearly true not only in observance of the bans on his music, but also in the ways the Germans sought to debilitate his general presence. In 1936, a statue erected in his honor, located in Leipzig, was brought down by anti-Semitics.5 Many composers were also asked to rewrite incidental music for Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream to replace Mendelssohn’s, a task which Richard Strauss (the symphonist responsible for Also sprach Zarathustra*) reportedly refused.6

Miraculously, much of Mendelssohn’s music was not destroyed, and his grave remained untouched for the duration of the war.

Gustav Mahler

Gustav Mahler’s rise to prominence was primarily as a conductor; he was renowned for his strict performance standards, especially as it pertained to opera. Like Mendelssohn, he was of Jewish ancestry, but converted to Christianity later in life. Mahler differed from Mendelssohn, however, in his motivation for converting, for in his case it would have increased the likelihood that he would be appointed to directorship of the Vienna Court Opera. These efforts were successful, and Mahler enjoyed a decade in the role.7 In the meantime, he would compose, although his compositions were outshined by his status as a conductor in his lifetime. It was not until later performances and recordings of his works, featuring the likes of Leonard Bernstein and other conductors, that his symphonies gained fame.8

Mahler was one of the last of what many scholars consider a long line of a subset of composers; many consider his death the end of post-Romanticism in music.9 His oeuvre, for the most part, contained lavish symphonies with grand numbers and unyielding passion. While this is not atypical of the Romantics, such characteristics, specifically those which accomplished the mission of exploring the human soul, were not the primary focus of exhibition again until there emerged Soviet composers like Dmitri Shostakovich in the 1920’s. And even notwithstanding the resurgence of Romantic techniques, never again was there someone who could apply them as uniquely as Mahler.

However, again like Mendelssohn, whatever contributions Mahler might have contributed to music were outweighed by his being descended from Jews. Even though Mahler was successful as a conductor, he was often the subject of mockery and jokes; many anti-Semitic peers and audience members found his mannerisms baffling, and his appearance peculiar. (See image above.) His techniques were often deemed puerile. But it was only posthumously, during World War II, that he met opposition in the form of outright banning; the Nazis barred performances of his music until the end of the conflict.10

But thanks again to the decisions of subsequent conductors, Mahler’s music is, as far as we may foresee, indefinitely preserved.

Erich Wolfgang Korngold

A large portion of classical music aficionados were first introduced to the genre through film music. Names like John Williams and Hans Zimmer are commonplace in discussions on the topic. Another name which enjoys that sort of popularity, at times, is Erich Korngold, who set the precedent for many film composing techniques in the early days of Hollywood. Although the titles of the films which he scored might sound unfamiliar to us now, the music persists. (Although, if such a list of films were compiled here, it would include properties like The Adventures of Robin Hood [1938], King’s Row* [1942], and Between Two Worlds [1944].11)

But for all of his impact on the film industry, still one thing kept him from realizing complete success in the Occident: his Jewish ancestry. While this is a recognizable pattern thus far, Korngold is the first composer in this article who was directly affected by Nazi German censorship in his lifetime. In fact, it was a direct result of Nazi activity, succeeding Germany’s annexation of Austria in 1938, that Korngold elected to exile himself in the United States and continue work in scoring American films.12 (Serendipitously, his first major task was to adapt Mendelssohn’s score for A Midsummer Night’s Dream into a film setting.)

Korngold enjoyed a relatively successful career in the United States, winning two Academy Awards and being nominated for three.13 His career as a composer dissipated in post-War Austria however, where attendance to compositional premiers was low and reconstruction had yet to yield those optimal conditions of which he had previously been a beneficiary.14

After his death, a number of works which Korngold did not intend for the theatre but instead for the concert hall have received a fair amount of appreciation. These included a symphony, chamber sonatas, and a violin concerto*. We are only left to wonder whether this catalogue, including his film scores, might even exist had Korngold remained in Europe in and after 1938; in chance, it is a tenuous margin.

Dmitri Shostakovich

The Post-World War II Soviet Union was infamous for its censorship. Stalin’s regime acquired a taste only for those works which portrayed Soviet art, culture, and principles as always triumphant; any works of the contrary were revised or discarded on government orders.

While there were many victims of this narrow selectivity, none have become so renowned or essential in deliberations on the issue as Dmitri Shostakovich. While his works tend to escape mass popularity due to their harsh dissonances, they are reflective of Shostakovich’s experiences and honorific of historic tragedies. (See the Symphony No. 11 in G*). But Shostakovich was continually displaced in his relationship with the government; consistently did he fear imprisonment or death.

In one such cataclysmic event, Shostakovich’s opera Lady Macbeth was received poorly, and a scathing review on the following morning denounced it as a work that refused to remove that “coarseness and savagery …from every corner of Soviet life.”15 Shostakovich was then declared an enemy of the people; his friends and family were targeted, and he learned firsthand the manner in which his later works would be scrutinized.

But Shostakovich remained ever resilient, placing subtle messages in his compositions that would signal to attentive listeners political opinions where the layman might not perceive it. His symphonic textures were thought in some ways to characterize Stalin, and in others Shostakovich sought to insert himself. For instance, in the Tenth Symphony, Op. 93, Shostakovich inserts a motif spelling “DSCH” all throughout the second movement.16

At best, this is only a rudimentary overview of the shifting dynamic between Shostakovich and the Stalin regime. But even as the former permitted silent protest, it stood and continues to stand as legitimate expression.

Maurice Ravel

Maurice Ravel refused to be described as an “Impressionist” composer.17 Nevertheless, his music is often associated with the Impressionist movement in French music. He enjoyed a status similar to that of Claude Debussy and has been described as one of the greatest orchestrators who ever lived. (See Daphnis et Chloe*). While his output was relatively small in comparison to other composers, this was typically made up for through his keen ear for detail, a great sense of tonal wash, and freshness.

But how might one produce works of such a caliber without external influence, both historic and contemporary, whenever it is so prevalent? Though this question was not satisfactorily answered, the Ligue Nationale pour la Defense de la Musique Française (National League for the Defense of French Music) thought doing so a worthy aspiration during World War I. This Ligue campaigned for a ban on all performances of classical music originating from Austria, Germany, and other opposing countries.

In response to a Ligue letter asking that he join these efforts, Ravel expressed the following sentiment:

“It would be dangerous for French composers to ignore systematically the productions of their foreign colleagues, and thus form themselves into a sort of national coterie: our musical art, which is so rich at the present time, would soon degenerate, becoming isolated in banal formulas.”18

After receiving this response, the Ligue barred performances of Ravel’s pieces until the end of the war. Ravel continued to support the war effort, albeit with new difficulties.

Every composer featured hitherto has been prevented from reaching public ears due to government activity; Ravel’s is the first instance in this article in which a composer’s expression is limited due to differences in political opinion solely. But this does well to highlight a broader inquiry Ravel posed: Should the globalization of the arts be limited during wartime, when peaceful trading is what ought to be the aspiration at any time of dispute?

Those composers whose careers were almost annihilated by the Nazis are studied and learned from today. Shostakovich felt that expression was still worthwhile even as it could have been self-destructive. Ravel recognized that borrowing ideas is a concomitant of the creative process. Such is the significance of maintaining a global effort to preserve the freedom of expression in the arts. The ICCPR, then, was the natural evolution of such an effort in the aftermath of the continued deprivation.

Suggested Works

Embedded within each listed work is a link to a performance of that work. Performers are credited in each individual video description.

Felix Mendelssohn:

- Violin Concerto in E Minor, Op. 64, MWV M 13

- A Midsummer Night’s Dream (incidental music), Op. 61, MWV O 14, (Intermezzo, Acts 4-5) – Wedding March

- String Octet in E-flat major, Op. 20, MWV R 20

- Quartet No. 2 in A minor for Strings, Op. 13, MWV R 22. (Mvt. I: Adagio-Allegro vivace)

Richard Strauss:

Gustav Mahler:

Erich Korngold:

Dmitri Shostakovich:

- String Quartet No. 8, Op. 110 (Mvt. II: Allegro molto)

- Symphony No. 11 in G minor, Op. 103

- 24 Preludes and Fugues, Op. 87, (No. 7 in A major – Fugue)

Maurice Ravel:

- Daphnis et Chloe, Suite Nos. 1 & 2

- Introduction and Allegro for Harp, Flute, Clarinet and String Quartet

- Miroirs (Mvt. III: Une barque sur l’ocean)

- Jeux d’eau

- String Quartet in F major (Mvt. I: Allegro moderato – très doux, and Mvt. II: Assez vif – très rythmé)

- United Nations General Assembly, International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, GA Resolution 2200A, (XXI) of 16 December 1966, entry into force 23 March 1976, in accordance with Article 49. ↵

- Taylor, Benedict. “Musical History and Self-Consciousness in Mendelssohn’s Octet, Op. 20.” 19th-Century Music 32, no. 2 (2008): 131–59. https://doi.org/10.1525/ncm.2008.32.2.131. ↵

- Clement, Albert. “Mendelssohn and Bach’s Matthew Passion: Its Performance, Reception, and the Presence of 70 Original Choral Parts in the Netherlands.” Tijdschrift van de Koninklijke Vereniging Voor Nederlandse Muziekgeschiedenis 59, no. 2 (2009): 141–55. http://www.jstor.org/stable/27764518. ↵

- Taylor, Benedict. “Mendelssohn, Time and Memory: The Romantic Conception of Cyclic Form (Cambridge University Press, 2011).” Cambridge University Press, 2011. ↵

- Wasserman, Janet I. “Felix Mendelssohn-Bartholdy & Fanny Mendelssohn Hensel: Portrait Iconographies.” Music in Art 33, no. 1/2 (2008): 353. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41818571 ↵

- Classic FM. “Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy – a Lutheran-Jewish Composer.” Accessed March 28, 2024. https://www.classicfm.com/composers/mendelssohn/guides/felix-mendelssohn-bartholdy-jewish-question/#:~:text=When%20Richard%20Strauss%20was%20asked. ↵

- Ditzler, Kirk. “Tradition Ist ‘Schlamperei’: Gustav Mahler and the Vienna Court Opera.” International Review of the Aesthetics and Sociology of Music 29, no. 1 (1998): 11–28. https://doi.org/10.2307/3108363. ↵

- Zychowicz, James L. “The Mahler Revival.” Chapter, 251–57, n.d. ↵

- Doub, Austin. “Gustav Mahler the Protomodernist.” Musical Offerings 11, no. 1 (2020): 17–28. https://doi.org/10.15385/jmo.2020.11.1.2. ↵

- Haas, Michael. Forbidden Music: The Jewish Composers Banned by the Nazis. Yale University Press, 2013. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt32bxjp. ↵

- Ranker. “List of Films Scored by Erich Wolfgang Korngold.” Accessed March 28, 2024. https://www.ranker.com/list/erich-wolfgang-korngold-movie-soundtracks-and-film-scores/reference. ↵

- Carroll, Brendan G. The Last Prodigy. Portland, Or. : Amadeus Press, 1997. ↵

- awardsdatabase.oscars.org. “Academy Awards Search | Academy of Motion Picture Arts & Sciences.” Accessed March 28, 2024. https://awardsdatabase.oscars.org/search/results/sort/1-Nominee-Chron. ↵

- Carroll, supra note 12 ↵

- Sumbur vmeste muzyki, Pravda, 28 January 1936. ↵

- GERSTEL, JENNIFER. “Irony, Deception, and Political Culture in the Works of Dmitri Shostakovich.” Mosaic: An Interdisciplinary Critical Journal 32, no. 4 (1999): 35–51. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44029848. ↵

- Mawer, Deborah, ed. “Musical Explorations.” Chapter. In The Cambridge Companion to Ravel. Cambridge Companions to Music. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000. ↵

- Maurice Ravel, Letter to the Committee of the League for the Defence of French Music. Letter. Bibliothèque nationale de France, Music Departement, rare book store, Nla 36 (01) ↵

5 comments

Sebastian Hernandez-Soihit

The ICCPR, signed in 1966, embodies the essence of free expression and information sharing, fundamental to our humanity. It’s a reflection of our innate desire to connect, learn, and express ourselves. Through the stories of Mendelssohn, Mahler, Korngold, Shostakovich, and Ravel, we see individuals stifled by censorship, yet driven by their passion for music and creativity. Their struggles highlight the human cost of silencing voices and the importance of defending artistic freedom as a cornerstone of our global community.

Naya Harb

This article is extremely important and very interesting. I never thought of freedom of speech and expression with music. These artists that faced suppression due to religious reasons, political, or ethnic reasons is very surprising to learn about. Great article Martin! Very captivating and I love the topic you chose it is very unique. Congratulations on being nominated, good luck!

Leaya Valdez

This article was amazingly written and thought out from start to end. It really made me think about how much censorship impacts the culture. It also shines lights that censorship has been going on for decades and a real eye-opener to see that sometimes the government can have too much control to the point where we cant have a diverse culture.

Quinten Mero

Amazing work! The right to freedom of expression is undeniably essential to the progression of modern society. When thinking of such freedoms my mind is in the habit of looking toward the U.S. Constitution as a form of documentation securing such rights. Therefore, it was interesting to learn that not only has this right been reinforced by the United Nations, but it is regarded by the institution as a civil right.

Jonathan Flores

Wow I thought this article was very well done and extremely eye opening. First, when we think of censorship we often think of those rights outlined in the first amendment, and overlook the censorship of things like art. With music being one of the most fundamental forms of art, it becomes increasingly clear that this is a very pertinent and serious issue which I think you expertly demonstrated. Second, I think the seriousness of the topic was accurately portrayed through your writing style. Overall, the article is very well done and well researched.