The early morning sky above Leyte Gulf already held the fire of combat when Captain David McCampbell made his initial approach, pressing the throttle handle forward inside of his F6F Hellcat. He urged his fighter on, into the chaos. The water’s surface gleamed a bright blue under the morning sun in stark contrast to the sky full of fire, AA flak exploding, and the glint of steel off the wings of an insurmountable formation of Japanese aircraft. McCampbell relayed a brief message to his wingman, Ensign Roy Rushing, just before banking hard to go head-on into the Japanese attack. McCampbell knew there was only enough ammunition for a few bursts left in his guns, yet the Japanese force outnumbered them nearly sixty to one.1

As McCampbell pulled back on his yoke, climbing high above the enemy formation, he felt the beads of sweat form under his flight mask. Below him, the Japanese fighters launched into a fury like an agitated hornet’s nest, quick, agile, and angry. Pulling down behind an enemy Zero, he hit the guns, all six .50 caliber machine guns erupted into a symphony of fire and destruction, ripping into the Japanese fighter as it fell from the sky in a trail of black smoke. Then again, a Zero fell into the sea as McCampbell attacked, not just to survive, but to hold the Japanese back and protect both the ships in the sea and the boots on the shore. The Allied liberation of the Philippines and the success of the Pacific seemed to rest solely on his shoulders.2

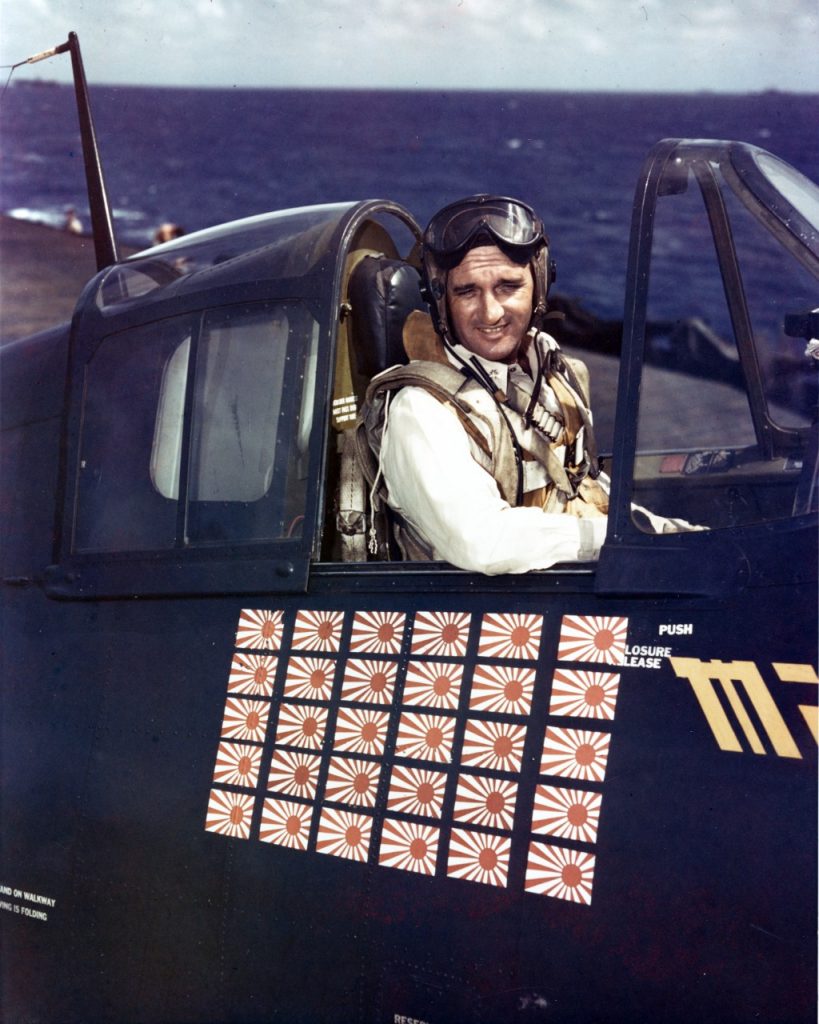

As the last shots had finally rang out, McCampbell had downed a record nine aircraft in a singular sortie, a feat that still stands untouched within U.S. naval aviation. As he moved to return his beaten and battered Hellcat back to the safe haven of his ship, the USS Essex, with fuel almost non-existent, and only two rounds left inside his trusty guns, the praise and cheer of his squadron crackled through his radio. This battle ended in victory, but the path it took to reach this day began not in success, but in the flames of loss.3

Two years before, McCampbell was forced to helplessly watch on in agony as his first aircraft carrier, the USS Wasp, dipped below the surface and into the depths after a torpedo strike. He survived that carnage, came to then command Fighter Squadron 15, and later Air Group 15, eventually earning the title of the most decorated naval aviator in American history.4 The hero in the sky above Leyte Gulf was born much earlier than that infamous morning, through discipline, fortitude, and a dissent to give up.

Before McCampbell emerged as the hero of Leyte Gulf, the stoic, strong ruler of the sky, he was just one of many naval officers atop the flight deck aboard the USS Wasp, seeing pilots return safely as he motioned them home with his set of brightly colored paddles. Aboard the Wasp, years before all the medals and praise, he learned something that cannot be taught within the confines of training: leadership is not born from comfort, but instead from hardship.5

Two years prior, World War II looked much different to McCampbell. Instead of flying planes, he was serving aboard the USS Wasp as a Landing Signal Officer (LSO), whose responsibility was to guide aircraft returning to the ship safely down onto its narrow flight deck. Standing mere inches from danger, McCampbell was tasked with watching approach angles, reading wind, and using hand signals to direct aircraft home. He still lacked some time before he became a legendary ace; instead, he was the one who made certain the pilots made it back from their missions.6 Even though he was not in the cockpit, his presence was distinct. Later, crewmates told of how he never needed to raise his voice; his presence alone commanded authority.

Disaster struck the USS Wasp on September 15, 1942. While providing support near Guadalcanal, a Japanese submarine launched a barrage of torpedoes aimed directly towards the hull, tearing a gash into her. Flames spread across the deck like a brushfire, igniting aviation fuel and melting steel into burning, molten debris. McCampbell, without worry for his own well-being was launched into action, directing sailors away from the fires, creating evacuation routes, and keeping an essence of order as the ship groaned beneath their boots. Orders rang out to abandon ship. McCampbell ignored these calls, pulling sailors away from the inferno; he was not going to leave until the deck was cleared.7

Flames and smoke billowed from the Wasp for hours before she finally gave in to the ocean’s beckoning call.8 Watching from his life raft, McCampbell did not feel just an obligation, but a personal duty in this war. The Wasp sinking molded him into something different, a more disciplined and steadfast sailor. He had now seen that even the most imposing ships could be sunk in moments. For the U.S. to win the war in the Pacific, they were going to greater pilots, greater tactics, and greater leadership. McCampbell vowed to become all three of them.

In the wake of the Wasp sinking, the Navy reassigned him from an LSO to now, a pilot. He walked away from his time on the Wasp changed and ready for a new role, commanding Fighter Squadron 15.9 What started as a tragedy blossomed into the start of his real journey. McCampbell was about to get a brand-new view of the war, this time from the cockpit.

Once McCampbell became the commander of Fighter Squadron 15 (VF-15), he chose a group of young, fresh pilots hungry for war but in need of discipline. Most of these men had never taken off from a flight deck, let alone flown into combat. Even still, McCampbell was determined to turn these men not just into a squadron, but a precise, deadly instrument of war. Each day began before the sun came up, working on formation flying, gunnery training, and carrier approaches. Learning the basics would build them into one of the premier squadrons in all the Pacific. McCampbell expected nothing less than perfection from his wingmen, for one small mistake in the air could prove fatal.10

McCampbell’s training was a furnace, hot and unforgiving; however, given enough time, the squadron began to bond just as steel would. The change was clear, the pilots spent every moment of the day together, mentally repeating maneuvers, tactics, and success. The squadron began to learn each other inside and out, anticipating one another’s movements, and learning to trust the guys flying wing to wing into battle with them. McCampbell was not just a voice telling them what to do; if they were in the air, so was he. When they were training, he was too. McCampbell’s stoic presence as well as his attention to detail bred a culture of excellence, one of which his men later attributed to their survival. Under his leadership, Squadron VF-15 earned the nickname “The Fabled Fifteen.”11

The success of VF-15 gained widespread attention, which led to McCampbell being selected to not only command his fighter squadron, but an entire air group (Air Group 15), aboard the aircraft carrier USS Essex. This was the first time in his short career as a pilot that he would be responsible for coordinating fighters, as well as dive bombers, and torpedo planes within large-scale combat operations. The stakes were becoming higher, and the missions more elaborate. McCampbell had to study the enemy’s tactics, memorize maps, and rehearse operations with his men until they could all perform them by pure instinct. When Air Group 15 launched from the USS Essex, they were led by a man forged from pain who would not accept failure.12

The first major test for Air Group 15 would come when the U.S. launched an attack on the Marshall Islands along with Truk Atoll, which was a very heavily fortified Japanese naval base. McCampbell, leading his men, flew straight into the teeth of the Japanese defense, evading Japanese AA fire like it was just another training mission, and his men following suit. With his fearless leadership, he coordinated the squadrons into one coordinated force. Under his command, Air Group 15 decimated the enemy, crushing ships, aircraft, and ground installations with terrifying effectiveness. The pilots yet again boasted about the calm presence of their commander, stating he never yelled over the radio; instead, he gave calm, confident orders. For many of the men within VF-15, this battle was the moment Campbell became more than just a commander; he became their leader.13

By the start of summer in 1944, Air Group 15 had gained the reputation of the most effective and feared carrier air group in all of the Pacific. McCampbell and his squadrons’ bond had grown tighter than ever before, but even though they kept racking up successful missions, intelligence warned of an enormous response from the Japanese fleet. They were gathering the remaining carriers and planes for one final attempt to stop America’s progress across the Pacific. The largest carrier battle in history was set to begin, and McCampbell was flying straight into the middle of it.14

By the middle of June 1944, the Pacific resembled a chess match, with both the American and Japanese ships lying in wait, ready to respond to the other’s next move. With Japan in dire need of stopping the United States’ advance into the Philippines, they launched their largest offensive attack since Pearl Harbor. Its target was the U.S. invasion fleet, which was just off the Marianas. Japan’s plan was bold: entice the U.S. air groups into a decisive ambush, destroy them, and take the upper hand in the Pacific. Aboard the USS Essex, McCampbell and his men studied reports from aerial reconnaissance missions, preparing themselves for the battle they knew would soon come. The tension Air Group 15 felt was thick; in the coming days, they would be in a battle to decide the fate of America’s naval air power in the Pacific Ocean.15

On June 19, just as the sun was breaking the horizon, the American fleet was thrown into a flurry as their radars lit up; the long-awaited attack had arrived. McCampbell and his squadron scrambled their fighters to the sky to meet the incoming Japanese formations. The Japanese were rolling the dice; they had launched over 300 aircraft from four different carriers, and their goal was to completely overwhelm the American fleet. What they made up in numbers, the pilots lacked in experience and training; even so, the weight of their nation’s future rested on their backs. As the Japanese force approached, McCampbell instructed his Air Group 15 to climb high above their attackers. Once in range, they all started to dive as the order “Engage” rang out over the radio.16

The event became known as “The Great Marianas Turkey Shoot.” Upon their initial attack, Air Group 15 fell into their training, ripping through Japanese aircraft. Zeroes erupted into flames as they succumbed to American bullets falling into the cold ocean below. Back up above the water’s surface was McCampbell, managing the battle with deadly precision. This battle put the majority of Japan’s Naval aviation program at the bottom of the Pacific Ocean.17

As the skies became dominated only by American fighters, the monumental feeling of this victory started to set in. As day turned to night, the entire airborne Japanese force was gone, over 300 aircraft were gone, and the majority still held their valuable veteran pilots. With this battle, Japan no longer had the power to wage a carrier war, a huge shift to the Americans’ likelihood of winning the Pacific.18

America’s victory in the Philippine Sea put Japan up against the wall and in need of retaliation. The next few months were relatively quiet in comparison; however, reports between Japanese brass were being intercepted that told a terrifying message. Japan was getting ready to launch its last attempt at pushing America back and preserving its spot in the war. This Offensive was called Shō-Go, (Operation Victory) and had the sole focus of destroying the U.S. fleet in Leyte Gulf. Air Group 15 was set to face their toughest foe yet, an enemy with nothing to lose. Even though word spread and they could no longer hide that their naval air power was all but gone, Japan devised Shō-Go. As more reports were intercepted by the U.S. Navy, Japan’s plan began to take shape; multiple Japanese fleets would move to the Philippines and attempt to lure the U.S. carriers away from land. It became apparent that Japan was going all in; losing this battle would mean losing its empire. McCampbell and his men, along with the rest of the fleet, realized this next battle would be an intensity they had not seen yet. The next few days were tense; everyone aboard the USS Essex knew of the attack and had to just wait for it. Everything stayed on alert, planes ready to scramble, attack plans constantly updating, men wired ready for battle, and in the middle of it all was McCampbell, who worried not only for himself but all of the men in Air Group 15.19

On October 24, 1944, as the night sky slowly gave way to dawn, the radio waves aboard the Essex erupted into news of an incoming Japanese attack from the north. This was the beginning of the Shō-Go counterattack. Under the cover of darkness, the Japanese fleet had made its way through the San Bernardino Strait, coming dangerously close to the American troops making landfall at Leyte. The Essex woke into immediate action, sailors rushed to their battle stations, and pilots readied to scramble.20 Just as the sun broke the horizon, McCampbell was climbing into his Hellcat. He knew this would decide the rest of the campaign in the Pacific; what he didn’t know was the legend he would soon forge.

As dawn broke and the first planes took off, McCampbell checked his fighter. Fuel wasn’t full, and his guns could use more ammunition, but none of this mattered to the Japanese, though, as they kept coming. His engines screamed to life as he readied to launch. With a quick salute to the deck crew, he was off heading straight for the enemy formations. Once in the air, McCampbell rendezvoused with his wingman, Ensign Roy Rushing. As they flew, the enemy formation appeared. An amalgamation of fighters, dive bombers, and torpedo planes was flying straight towards the carriers. With the total number of aircraft clearing 60, the two pilots showed no fear taking the fight to the enemy; there was no time to wait for reinforcements without risking the lives of the men making landfall. Suddenly, McCampbell released a flurry of .50 caliber fire, punching through the lead zero, as it fell to the ocean below, and the fight was on.21

The sudden attack by just two American fighters confused the Japanese pilots. Using this to his advantage, McCampbell made multiple passes, diving into the formation, firing a burst, then climbing back up to keep his advantage. Reports would later show McCampbell was responsible for shooting down nine planes himself, a feat this impressive hasn’t been matched in naval aviation history. It was later said McCampbell radioed, saying he only had a few bursts of ammo left and little fuel as he turned to face two more Japanese fighters, downing them both. This level of courage is why McCampbell is the most decorated and feared aviator in U.S. naval history.22

Both men, low on ammo and fuel, worked as a team covering each other’s back as they laid waste to the Japanese formation. It seemed as if one man flew both planes. Both fighters shot down multiple Japanese fighters while taking no fatal damage themselves. Seeing the difference, the Japanese withdrew, knowing they couldn’t match the skill of the American fighters. McCampbell and Rushing had single-handedly broken a coordinated attack from over 60 Japanese aircraft, changing the course of the battle.23

Low on ammunition and even lower on fuel, McCampbell changed his heading back to the Essex. During his approach, the realization of what the two had done dawned on the flight crew. McCampbell had nine kills. Everyone lined the deck as his Hellcat touched down, as he opened his canopy and was greeted by cheers, he remained quiet, for he didn’t know what he had just accomplished. He was just thankful his wingman and he had made it home safely.24

The attack that McCampbell had repelled never made it to the landing force at Leyte. He and Rushing had made the first break in Japan’s eventual losing offensive, the loss of their ultimate gamble.25 The Battle of Leyte Gulf is widely regarded as the moment that killed Japan’s naval power. The war for McCampbell was almost over, and this was his final impression.26

On October 26, 1944, just two days after the battle orders came in, McCampbell’s combat tour had reached its conclusion. In the end, he had flown more missions and had more success than any carrier air group commander in the Pacific; he had also accomplished feats no one had done before or ever would do. On his final day, McCampbell flew one more reconnaissance mission over the Philippines, checking for any remaining enemy planes. After he returned to the Essex, the war was not over, planes still took off, operations carried on, but a stillness was present as if a weight was lifted from McCampbell; his time in battle was over.27

Upon arrival stateside, McCampbell was no longer waking to war, but instead was met with parades, press conferences, reporters, and news stories. He was no longer seen as a leader but a celebrity; he was taken by the navy to be the focal point of war bond tours, where crowds formed to see the legend who had downed nine aircraft in one sortie and became an ace twice. McCampbell was courteous to the women and children who asked questions and wanted autographs, but he could not tell them of the horrors he had seen, so he just smiled. In his private hours, the weight of war fully weighed on him, remembering the soldiers he fought alongside and those he buried. Many families received letters from McCampbell speaking of not himself but of the brave men he fought alongside. The medals and records he held meant nothing when compared to the lives he got to be a part of during and after the war; his leadership isn’t measured by accomplishment but by the honoring of those who sacrificed so he lived.28

From the burning decks of the USS Wasp to the fiery skies of Leyte Gulf, McCampbell left his mark as an extraordinary officer who turned into a fierce warrior. His story began in pain, fire, and loss, but was shaped by perseverance, leadership, and heroism. Every moment he spent training, fighting led him to the decisive day above Leyte Gulf, where his legend was born from an ordinary LSO to the savior of his entire fleet.

By the end of McCampbell’s career in World War II, he held multiple records that still are unbroken. 34 aerial victories, the most of any naval aviator, and he is still the only aviator to be awarded the Medal of Honor for actions while serving as a carrier group commander. He received the Medal of Honor, Navy Cross, Silver Star, Legion of Merit, and the Distinguished Flying Cross.29 Throughout his life, McCampbell never referred to these awards; instead, when anyone asked about his experiences, he told of the brave men of his squadron, as they were the ones who did the flying.

Air Group 15, under the command of McCampbell, destroyed more enemy units than any other carrier group in the Pacific.25 Historians credit the realization of power held by carrier air power to McCampbell, and he helped light the way for modern aviation strategy.31

When the war became a distant memory, medals sat untouched, and the public eye faded, the man who was Captain David McCampbell remained. The day that could have changed the tide of war for Japan in the Pacific instead became “The Day of the Aces.”

- Thomas McKelvy Cleaver, “Relentless in Battle,” HistoryNet, May 2, 2014, https://www.historynet.com/relentless-in-battle/. ↵

- Thomas McKelvy Cleaver, “Relentless in Battle,” HistoryNet, May 2, 2014, https://www.historynet.com/relentless-in-battle/. ↵

- Thomas McKelvy Cleaver,“Relentless in Battle,” HistoryNet, May 2, 2014, https://www.historynet.com/relentless-in-battle/. ↵

- “Pacific Wrecks – Captain David McCampbell – U.S. Navy (USN) Fighter Pilot and Ace,” accessed November 2, 2025, https://pacificwrecks.com/people/veterans/mccampbell/. ↵

- “Profiles in Courage: David McCampbell – Largest U.S. Army Veteran Directory + Service History Archive,” TogetherWeServed, accessed November 2, 2025, https://army.togetherweserved.com/dispatches-articles/26/303/Profiles%2Bin%2BCourage%3A%2BDavid%2BMcCampbell/. ↵

- Thomas McKelvy Cleaver, “Relentless in Battle,” HistoryNet, May 2, 2014, https://www.historynet.com/relentless-in-battle/. ↵

- Mason B. Webb, “The Death of the USS Wasp,” Warfare History Network, https://warfarehistorynetwork.com/article/the-death-of-the-uss-wasp/. ↵

- Mason B. Webb, “The Death of the USS Wasp,” Warfare History Network, https://warfarehistorynetwork.com/article/the-death-of-the-uss-wasp/. ↵

- “Pacific Wrecks – Captain David McCampbell – U.S. Navy (USN) Fighter Pilot and Ace,” accessed November 2, 2025, https://pacificwrecks.com/people/veterans/mccampbell/. ↵

- David Lee Russell, David McCampbell: Top Ace of U.S. Naval Aviation in World War II (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, 2019, 45-50. ↵

- David Lee Russell, David McCampbell: Top Ace of U.S. Naval Aviation in World War II (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, 2019, 45-50. ↵

- David Lee Russell, David McCampbell: Top Ace of U.S. Naval Aviation in World War II (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, 2019, 48-51. ↵

- Chris Marks, “The Air Raid on Truk Lagoon in April 1944,” Warfare History Network, June 2021, accessed November 7, 2025, https://warfarehistorynetwork.com/article/truk-lagoon-air-raid-april-1944/. ↵

- “Profiles in Courage: David McCampbell – Largest U.S. Army Veteran Directory + Service History Archive,” TogetherWeServed, accessed November 2, 2025, https://army.togetherweserved.com/dispatches-articles/26/303/Profiles%2Bin%2BCourage%3A%2BDavid%2BMcCampbell/. ↵

- “Profiles in Courage: David McCampbell – Largest U.S. Army Veteran Directory + Service History Archive,” TogetherWeServed, accessed November 2, 2025, https://army.togetherweserved.com/dispatches-articles/26/303/Profiles%2Bin%2BCourage%3A%2BDavid%2BMcCampbell/. ↵

- Alvin Townley, “October 24, 1994: David McCampbell Downed More Enemy Aircrafts Than Any Other Naval Aviator—Ever,” The History Reader, October 24, 2011, https://www.thehistoryreader.com/military-history/october-24-1994-david-mccambell-downed-enemy-aircraft-naval-aviator-ever/. ↵

- Alvin Townley, “October 24, 1994: David McCampbell Downed More Enemy Aircrafts Than Any Other Naval Aviator—Ever,” The History Reader, October 24, 2011, https://www.thehistoryreader.com/military-history/october-24-1994-david-mccambell-downed-enemy-aircraft-naval-aviator-ever/. ↵

- Thomas McKelvy Cleaver, “Relentless in Battle,” HistoryNet, May 2, 2014, https://www.historynet.com/relentless-in-battle/. ↵

- “H-Gram 038 – 2: Leyte Gulf in Detail,” Naval History and Heritage Command, November 25, 2019, accessed November 7, 2025, https://www.history.navy.mil/about-us/leadership/director/directors-corner/h-grams/h-gram-038/h-038-2.html. ↵

- “Profiles in Courage: David McCampbell – Largest U.S. Army Veteran Directory + Service History Archive,” TogetherWeServed, accessed November 2, 2025, https://army.togetherweserved.com/dispatches-articles/26/303/Profiles%2Bin%2BCourage%3A%2BDavid%2BMcCampbell/. ↵

- “Profiles in Courage: David McCampbell – Largest U.S. Army Veteran Directory + Service History Archive,” TogetherWeServed, accessed November 2, 2025, https://army.togetherweserved.com/dispatches-articles/26/303/Profiles%2Bin%2BCourage%3A%2BDavid%2BMcCampbell/. ↵

- “Profiles in Courage: David McCampbell – Largest U.S. Army Veteran Directory + Service History Archive,” TogetherWeServed, accessed November 2, 2025, https://army.togetherweserved.com/dispatches-articles/26/303/Profiles%2Bin%2BCourage%3A%2BDavid%2BMcCampbell/. ↵

- “Profiles in Courage: David McCampbell – Largest U.S. Army Veteran Directory + Service History Archive,” TogetherWeServed, accessed November 2, 2025, https://army.togetherweserved.com/dispatches-articles/26/303/Profiles%2Bin%2BCourage%3A%2BDavid%2BMcCampbell/. ↵

- Thomas McKelvy Cleaver, “Relentless in Battle,” HistoryNet, May 2, 2014, https://www.historynet.com/relentless-in-battle/. ↵

- Thomas McKelvy Cleaver, “Relentless in Battle,” HistoryNet, May 2, 2014, https://www.historynet.com/relentless-in-battle/. ↵

- “The Battle of Leyte Gulf | Remembering WWII,” Coconut Times, accessed November 2, 2025, https://mobile.coconuttimes.com/articles/Remembering-WWII/The-Battle-of-Leyte-Gulf. ↵

- “H-Gram 038 – 2: Leyte Gulf in Detail,” Naval History and Heritage Command, November 25, 2019, accessed November 7, 2025, https://www.history.navy.mil/about-us/leadership/director/directors-corner/h-grams/h-gram-038/h-038-2.html. ↵

- “Pacific Wrecks – Captain David McCampbell – U.S. Navy (USN) Fighter Pilot and Ace,” accessed November 2, 2025, https://pacificwrecks.com/people/veterans/mccampbell/. ↵

- “Pacific Wrecks – Captain David McCampbell – U.S. Navy (USN) Fighter Pilot and Ace,” accessed November 2, 2025, https://pacificwrecks.com/people/veterans/mccampbell/. ↵

- Thomas McKelvy Cleaver, “Relentless in Battle,” HistoryNet, May 2, 2014, https://www.historynet.com/relentless-in-battle/. ↵

- Thomas Hone, “Replacing Battleships with Aircraft Carriers in the Pacific in World War II,” Naval War College Review 66, no. 1 (2018), https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/nwc-review/vol66/iss1/6. ↵

1 comment

Maya Inomata Hernandez

I liked how you mentioned that the Japanese pilots late in the war weren’t as experienced. That detail made the whole situation intense.