In the eleventh century, the Iberian Peninsula was very different from how we know it today. Spain and Portugal did not exist as unified territories or countries. Instead, the dominant civilization then was Islamic. Muslims had entered the peninsula in 711 C.E., and had forced the weak Christian forces to a small territory in the north of the peninsula. It took the Christians a very long time to reorganize to be able to show a little capacity of resistance towards the powerful Islamic empire. However, after many years of Muslim dominance, the northern Christian kingdoms assembled some forces and started the long process of regaining territory from the Islamic empire, a process that is known as “La Reconquista.” This was the advance of the Christian kingdoms to the south of the peninsula, winning territory little by little and finally recovering the control over the entire peninsula in 1492 with the conquest of Granada. In the eleventh century, we find an important story of La Reconquista, because it witnessed radical changes in the structure of al-Andalus, the land and rule of the Muslims. The caliphate of al-Andalus ended up crumbling in 1031, and the Andalusian territory was divided into the Taifa kingdoms, where the different rulers fought each other. They were each motivated by their desire for power, ambitions that the Christians would know how to take advantage of very well. With the Islamic empire starting to show some weaknesses, one name stands out in this century: Rodrigo Díaz de Vivar, known as “El Cid.” He was an historical and legendary figure of La Reconquista. He has gone down in history as “el Campeador” (expert in pitched battles.) During his lifetime in the eleventh century, El Cid built his reputation as one of the most feared leaders on the battlefield, fighting against the Muslims and, on some occasions, even against Christian troops! His story is linked to the Christian king of Castile, Alfonso VI, who would have many ups and downs. Alfonso’s actions in this period were a big cause for el Cid’s most known achievement: the battle and conquest of the city of Valencia.1

Before that battle, el Cid was a soldier fighting in name of King Alfonso VI of Castile. However, in 1079, an important event changed El Cid’s future. At the Battle of Cabra, El Cid’s non-authorized excursion into Granada highly annoyed Alfonso. That event was the king’s official reason for sending El Cid into exile, although several others are more possible or may have contributed to this decision: jealous nobles turning Alfonso against El Cid, Afonso’s own dislike of El Cid’s popularity, an accusation of keeping some of the monetary collections of the kingdom, and accusations of El Cid’s disrespect of powerful men in the royalty. For one reason or another, El Cid lived his first exile from the kingdom of Castile, which brought shame (probably unfairly) to his name. However, not much later, in 1086, the great Almoravid (one of the greatest dynasties of the Islamic empire) invasion began, forcing the Christians to a retreat. King Alfonso barely managed to escape capture. This defeat actually served El Cid well. Terrified after this painful defeat, Afonso withdrew El Cid from exile, asking for his services once again to fight the Almoravids back. However, in November 1088, when Alfonso VI asked El Cid for help in attacking the Almoravids in the south-east of the peninsula, the troops of Alfonso and El Cid did not meet for unknown reasons. Because El Cid did not find Alfonso, he set up his camp somewhere at a different place. There he learned that King Alfonso, furious at not receiving the help of “El Campeador,” had declared him a traitor, the most serious disgrace for a knight, and consequently he seized all of El Cid’s estates and again sentenced him to a second exile. It was then that El Cid decided never to serve any lord again but rather act at his own risk. It was a turning point in his life that would be decisive in his greatest achievement, the conquest of Valencia. In his second exile, El Cid and his loyal private army continued to win lands from the Muslims in the Levant (Eastern coast of the Iberian Peninsula). But this time, he intended to build an independent lordship at the cost of the Muslim Taifas. Using his unquestionable military talent, the Campeador won a combination of Muslim territories and forced them to pay him tribute. Around this time, in 1090, with an established lordship and a combined Christian and Moorish army, El Cid began to move in order to expand his own power to the Moorish Mediterranean coastal city of Valencia, then ruled by al-Qadir.2

In October of 1092, El Cid began a siege of Valencia. The siege lasted many months and finally found an ending in May 1094, when he occupied Valencia removing the governing Almoravid group, and assuming control of the city. Alfonso used the good image that this quick occupation of Valencia would bring to his kingdom to say that “officially” El Cid ruled in his name; nonetheless, he was fully independent. Actually, the city was both Christian and Muslim, and both Moors and Christians served in the army and as administrators. Nevertheless, this quick occupation was not the end of the story. El Cid knew that a strong reaction from the Almoravids would come, a reaction for which King Alfonso did not send help at all, which is why El Cid’s victory against the Almoravids is even more legendary.3

The expected response came in August 1094, when an immense Almoravid army entered the peninsula from Africa. Its goal: taking Valencia back. It is important to note that the Almoravid forces had many advantages over El Cid’s forces, the first of which was the size of its army: its numbers were over 25,000, while El Cid’s loyal forces accounted for less than 4,000 men. Also, the Almoravids had military advantages and powers, like having 80 percent of its army mounted, but with very little armor protection. Given this handicap, El Cid knew that a heavy charge was unlikely, and he expected that, in case of an open battlefield, the Almoravids would try to get rid of his heavy cavalry with their light, skillful cavalry, and go head-to-head afterwards with their large unprotected numbers. Facing this difficult situation, Rodrigo began to plan his defense. He was educated in Latin and Arabic, which had allowed him to learn the battle and siege tactics of the greatest armies up to that time. In fact, his title of “Campeador” comes from the Latin campi doctoris (a battle planner and teacher). Given his numerical inferiority, his advisers thought that he needed to fight defensively. But he knew that he had to completely eliminate the Almoravid threat from Valencia, and that would only be possible by taking the enemy by surprise outside the city walls, which seemed like suicide to many. Nonetheless, Rodrigo had demonstrated his ability to discover and use his opponent’s weaknesses in his favor. This time was no exception, and he found a weak link in the strong Almoravid chain: its strict tactical organization, discipline, and close supervision, which was an effective but slow way of operating. He recognized that if he could attack by surprise and before they could organize and act according to their protocols, his skillful knights and the quality of their weapons, protections, and horses, could bring the victory home.4

To make this strategy effective, Rodrigo needed to make sure that the Almoravid army would mobilize at the place he wanted, because that would give him the advantage by knowing the battlefield, where he would prepare the land for his strategy. Four miles up the “Río Túria” (Valencia’s River) and northwest of the city was the esplanade of “El Cuarte.” Rodrigo anticipated that the Almoravids would like that place to settle down if they knew about it, because the plain was the perfect location to feed their horses, mules, camels, and elephants. To be 100% certain that the Moors acted as he wanted them to, he sent anti-Almoravid Muslims loyal to him to sneak into the enemy’s forces to meet their leaders and recommend to them that they should settle down at El Cuarte.5

What the Almoravids did not know is that the Valencian late summer or early Autumn usually brought heavy rains, which typically brought huge showers of water, favoring floods in early October that often destroyed harvests. When El Cid’s spies informed him that the enemy would arrive in Valencia half through their holy month of Ramadan, Rodrigo recognized a second chance to move the balance in his favor. As we know, Ramadan prohibits Muslims from ingesting foods and drinks from sunrise to sunset. After this day-light fasting, Muslims would usually sleep late into the day after eating the entire night, which made them very unproductive during the day. Therefore, Rodrigo realized that the Muslims would be at their weakest point at the end of Ramadan, which fell around October 14. Rodrigo’s plan of luring the Almoravids to where he wanted them worked out perfectly, and Almoravid army arrived at El Cuarte in mid-September. Valencia, as usually happens in the summer, had seen no water for months, and the entire city, especially the farmers, kept an eye on the sky as October arrived, knowing what would happen. As expected, in October 1094, Valencian citizens woke up one day and saw that 25,000 visitors were outside the walls of the city politely asking to come in. As far as their sight could go, they saw the campaign tents of a huge army. History books tell how for many days, the citizens of this Mediterranean city listened to an unstoppable thunder of thousands of Almoravid drums, only interrupted when some friendly flaming arrows flew into the interior of the city. Objectively, the Moors’ victory looked like something certain. The Almoravid forces set up a siege around the city, unfolding a huge army of archers, spearmen, javelin throwers, horsemen, and elephants.6

On the tenth day of the siege, Valencia’s farmers informed Rodrigo that they had seen birds randomly appearing and keeping their flight so close to the ground that they almost skimmed it, which meant that the “Gota Fría” (the rainy season) was almost there. Indeed, that night, black clouds covered the city of Valencia. On the morning of October 14, after days of heavy rain, 130 men waited behind the west doors of the city of Valencia, dismounted. As the sun rose from the Mediterranean eastern side, the western city gates opened slightly and the soldiers snuck out. More asleep than awake and facing the rising sun, the Almoravids did not notice El Cid’s forces leaving the city. Initially, the siege machines had instilled fear in the Valencians, but Rodrigo saw an opportunity with them: his men placed dry straw under the machines and set them on fire, causing huge flames that covered the entire machinery. While that was happening, Rodrigo separated the rest of his men into two groups inside the city. At his signal, they left intramurals, with him leading the forces on his famous horse “Babieca.” With his sword “Colada” (famous and preserved to this day), he started the battle that would be remembered as one of the most important battles of La Reconquista with a phrase that would be used in the many conquests of the Spanish empire yet to come: “For God and Santiago, and at them!” The first group led by El Cid charged through the enemy masses and opened a crack in its forces amidst the chaos that was now the Almoravid army. When his men had surpassed the Almoravid cordon, they assembled around his leader, drawing the attention of the Almoravids who had now reorganized. With the bloodlust Moors facing this group, the second group of El Cid’s men charged into them from the rear. The rain turned into a deluge and, as expected by Rodrigo, the Turia river had increased its flow so much that it caused huge torrents, entering the Almoravid camp at El Cuarte and taking pavilions, campaign tents, food and war supplies with it, mainly caused because Rodrigo had ordered to stop the functioning of the irrigation system of the fields of Valencia, so that the water would not have any other option than to accumulate on the surface. After the first attack, Rodrigo’s forces had mobilized and hidden in the woods, waiting for the Almoravid forces to escape the waters and try to reorganize. As the Almoravid horsemen prepared for an attack, Rodrigo’s men came out of the woods and charged for a last time. According to clerics that recorded the battle, the victory was “achieved with incredible speed and with few casualties among the Christians.”7

The victory of El Cid in Valencia was not only celebrated by his forces, but also by the Christian kingdoms of the peninsula and by Royal courts all over Europe, because it meant the expulsion of the Muslims from a strategic city in the process of La Reconquista. Even if it was not Rodrigo’s main goal, the conquest of Valencia marked a big withdrawal in the already broken Muslim forces, accomplishing a big milestone in the Christian’s advance to the south of the Peninsula. With the forces of el Cid in Valencia, the Christian kingdoms had a very important base from which multiple victories would follow over the years, leading to the final conquest of Granada. In the following years after the battle, Rodrigo brought the last two Muslim castles in the region under his control and defeated another Almoravid invasion. At Valencia, Rodrigo added an essential chapter to the story of La Reconquista. Thanks to his unexpected attack, he defeated the Muslim forces, and became the sole Christian leader of the eleventh century to defeat the powerful Almoravid army in open battle. When the Christians searched for a national hero during the next few centuries of fighting the Muslims, the legend of El Cid Campeador would inspire them.8

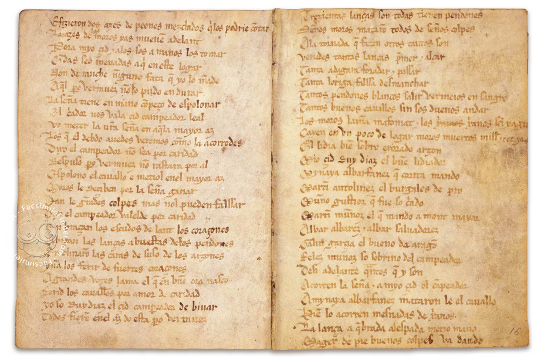

The huge achievements in El Cid’s life, his great war tactics and strategies, his tenacity and courage, his great leadership tactics, and the immense legacy that he constructed during his life, were highlighted in the conquest of Valencia, glorifying his name, which would be remembered as one of the most important ones in Spanish history. His story and the conquest of Valencia are studied still today through important texts written centuries ago. The most important of those texts is the famous “Cantar del mio Cid”: a collection of “cantares” (short poems) about el Cid’s life where his major accomplishments are recorded and glorified. It is because of works like this one that the figure of el Cid is seen in Spain, still today, as one of those legendary figures whose story is passed from generation to generation, and who embodies Spanish history and past glory.9

- Alfonso Boix Jovaní, “Rodrigo Díaz, de Señor de La Guerra a Señor de Valencia,” Olivar 8, no. 10 (December 2007): 185–92, http://www.scielo.org.ar/scielo.php?script=sci_abstract&pid=S1852-44782007000200012&lng=es&nrm=iso&tlng=es. ↵

- “El Cid,” New World Encyclopedia, accessed February 22, 2022, https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/El_Cid. ↵

- Alfonso Boix Jovaní, “Rodrigo Díaz, de Señor de La Guerra a Señor de Valencia,” Olivar 8, no. 10 (December 2007): 185–92, http://www.scielo.org.ar/scielo.php?script=sci_abstract&pid=S1852-44782007000200012&lng=es&nrm=iso&tlng=es. ↵

- Ronald R. Gilliam, “The Genius of El Cid,” HistoryNet (website), August 3, 2011, https://www.historynet.com/the-genius-of-el-cid.htm. ↵

- Estanislao de Kotska Vayo, La conquista de Valencia por el Cid (Editorial Verbum, 2021). ↵

- “The Conquest of Valencia in the ‘Cantar de Mio Cid’ – ProQuest,” accessed February 25, 2022, https://www.proquest.com/openview/e3b4610baecd7bbab942c8985b78c856/1. ↵

- Richard A. Fletcher, The Quest for El Cid (Oxford University Press, 1991), 123-134. ↵

- Raquel Crespo-Villa, “Tres modelos para la reconstrucción posmoderna del héroe medieval: La figura de Rodrigo Díaz de Vivar en tres novelas históricas españolas del siglo XXI,” 2015, https://repositorio.uam.es/handle/10486/671665. ↵

- Jack Weiner, El Poema de mio Cid: el patriarca Rodrigo Díaz de Vivar trasmite sus genes (Edition Reichenberger, 2001), 77-85. ↵

11 comments

Louie M. Valdivia

I enjoyed reading your article on El Cid. When I was very young I saw the movie with Charleton Heston and didn’t understand what was going on. Now I have a better understanding of who he was and situation in Spain at the time. I always believed that he was the one responsible for ridding Spain of the Moors and restoring Christianity. But apparently, he was not since he also commanded Muslim armies.

Seth Roen

Honestly, I have never heard of Rodrigo Díaz de Vivar before reading your article. It is a pity that many nobles were against him in his early career, but as you point out, that seems to be a blessing in disguise. He once again proved that a prepared quality seems to trump and more significant force anytime, regardless of the enemy.

Kelly Arevalo

I loved your article! This is a story I’ve known about since I was a child, although, to be honest, I thought el Cid lived only in fiction. He was an incredible military leader and a key figure in Spain or European history in general. So much so that I have met Spanish people who knew El Cantar del Mio Cid by heart. I think you managed to convey the heroism and strength that associate with El Cid’s story. Good job!

Jesslyn Schumann

Hi Daniel!! First off, I wanted to congratulate you on the nomination! Prior to reading, I remember hearing about the article you wanted to write about and I was super excited to be able to read it. Now that it is here, I am glad to say that this was a very well written article. I had no idea that El Cid had that much impact on the history of Spanish history. Though I did not know much about it prior to reading, I am glad that I was able to get a little bit of insight on it! Again, I hope you are able to pull through with your nominations! Best of luck!

Cassandra Cardenas-Torres

this was a really well written article I learned a lot of knew things I didn’t know before . I love how distractive your article was and how you started from the very beginning with the history. coming from a hispanic house hold here is America I think that we sometimes over look spanish literature which was great to learn about. As congratulations on the nomination!

Katelyn Canales

Hello Mr. Gimena, a huge congratulations on receiving a nomination for your article! I really enjoyed reading about El Cid Campeador, and his very detailed journey in the conquest of Valencia. I can imagine how much effort you put into this European studies article because of the complex sources you listed, and the accurate information you provided. This was such a great find! I mostly loved the topics of his war tactics, and El Cid Campeador’s war strategies.

Chris Ricondo

Congratulations on your nomination and publication of your article! It was fascinating because I was unfamiliar with El Cid and his ambition during the Reconquista. It was thrilling to follow El Cid’s combat strategy and conquest of Valencia in this article. I had no notion he had his own army or that he had conquered Valencia on his own. Also, he defeated an army five times his own size and now I can see why he is honored as a Reconquista hero.

Matthew Gallardo

Reading about El Cid was very intriguing. I knew somewhat of his achievements but not the lengths of them and how big they were. I had no idea he had a private army or that he captured the city of Valencia all on his own. And even better, defeating an army more than 5 times the size of his. With this I understand better why he is so revered as a hero of the reconquista. This was a great read!

Andrew Ponce

Congratulations on the article nomination! This article is very good for people who are unfamiliar with Spanish literature. Many people do not have the opportunity to read about such an important character in world history. The author was able to keep the author engaged through very descriptive writing and action style writing. Great job to the author for finding such an unknown topic to North America, and informing the audience in such an interesting way.

Madeline Chandler

This was an extremely well-written article, and it was so detailed. I love the detail in this article. It was so interesting because I do not have much knowledge El Cid and his mission during the Reconquista. This article was so exciting to follow El Cid’s battle strategy and his conquest of Valencia. His military strategies and leadership during the Reconquista left many leaders following his ideas.