The Wild West was a lawless place, where justice was determined by who had the fastest draw and the better aim, and where the law could not span every corner of a town, causing people to fear for what tomorrow might hold. It was a time and place where legends were made in the heat of a standoff; those who survived would be remembered in history, and many died trying. One of these legends is that of Elfego Baca, the man who stood against impossible odds and walked away alive.

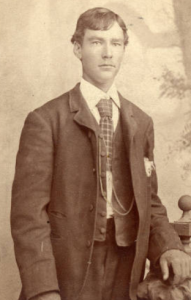

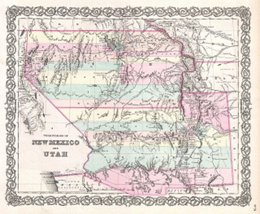

It was 1872, in the small town of Frisco, New Mexico. Lawless Texan cowboys ran rampant, leaving blood and victims in their wake. They rejected the Mexicans that were there first, shooting cats and dogs and torturing the local population. At that time, Elfego Baca was living in Socorro with his grandparents. He heard the horror stories of these cowboys who were castrating individuals and using them as target practice.1 They terrified law enforcement, and the sheriff of Frisco, Deputy Sheriff Pedro Sarracino, had left for Socorro, where he met Baca. Baca was disappointed to hear that even the sheriff was unable to stand up to these criminals, but Sheriff Sarracino told him that no one could stand up to them and survive. But Baca, at only nineteen years old, stated he would “show them that there is at least one Mexican in the country who is not afraid of an American cowboy.”2

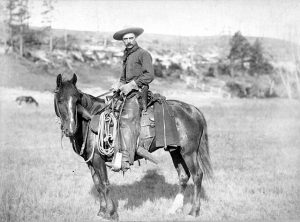

Sheriff Sarracino handed his badge over to Baca and wished him well as Baca headed back to Frisco.3 When he arrived, he headed over to a local saloon where the Texan cowboys were drinking; and as luck would have it, one of them started to shoot up the saloon. After bullets shot past Baca, he decided enough was enough and went over and announced to the cowboy, Charles McCarthy, that he was the new sheriff and that that type of behavior would no longer fly in this town. Standing at only 5-foot-7, Baca was nevertheless not intimidated by McCarthy. But when McCarthy shot off Baca’s hat, and Baca did not so much as blink, McCarthy realized he was messing with a very different kind of sheriff.4 McCarthy then tried to flee the saloon, but Baca proceeded to arrest McCarthy, and in the struggle, other Texans attempted to stop Baca, and shots were fired. This caused one of the horses nearby to fall on one of the cowboys. Whether the horse was shot by Baca or spooked by all the gunfire did not matter to the Texan cowboys; this new sheriff had killed one of their own. Baca took McCarthy to Sarracino’s house as a makeshift jail, where he would stay until his trial. That same day, a dozen Texan cowboys showed up to the “jailhouse” prepared for a fight, wanting McCarthy to be released or else. What the cowboys were not aware of was that Baca was very familiar with shooting. He confronted the men, telling them to leave or he would count down from three and start shooting. Baca liked to count fast, and in the blink of an eye drew his gun, the Colt single action also known as the “peacemaker,” and shot one of the cowboys in the knee.5 True to its name, the Colt made the cowboys disperse after seeing what Baca was capable of, but they had been embarrassed twice now by Baca, and they would not forget that.

The Texans realized they could not beat Baca alone, so they decided to send a messenger to Alma, a town close to Frisco, where they would employ the help of the sheriff. The plan was to have Baca arrested for the killing of the cowboy, and other cowboys rode to Frisco and to the surrounding area to sound the alarm about an uprising happening. While that was not true, it still caused multiple cowboys to ride to Frisco expecting a fight, and when they saw there was none, they decided to wait for the messenger to return from Alma. Soon after, Deputy Dan Bechtol and other cowboys from Alma arrived in Frisco, and the cowboys rode out to ensure that McCarthy got what they considered a fair trial. Two of them went and told Baca to bring McCarthy to the plaza for his trial and warned Baca of the cowboys that were waiting; but Baca was never one to shy away from a challenge and took McCarthy to the plaza. As word spread that there was a Hispanic killing Texans and taking them hostage, more and more cowboys arrived, totaling eighty.6

Deputy Bechtol took McCarthy into a nearby house, where he was to stand trial. Baca left the courthouse first, dashing into a jacal, which was a house found throughout the southwest parts of the United States and Mexico.7 Baca told the owner to leave with his family since things could get bad, and as the family left, McCarthy left the courthouse, having been fined $5 for his crimes. The cowboys who had gathered for the event felt that justice was still lacking, and Baca had to be held responsible for his crimes. They had seen Baca flee into the jacal, and one Texan named Herne went and knocked on the door. When Baca did not reply, Herne started kicking the door, demanding to be let in. Baca replied by shooting him with his dual .45, hitting his abdomen, where he died from his wounds shortly after. Some of the Texans attempted to get Deputy Bechtol to help them arrest Baca, but for unknown reasons, he declined, leaving the cowboys on their own, and the siege began.

The shooting attracted a wide variety of people; some approached the jacal and tried to negotiate a peace with Baca in Spanish. There was a slight issue in their plan; Baca actually did not speak a lick of Spanish, but he spoke bullets and fired off a few more shots to anyone that got too close.8 The cowboys understood that and decided to reply, shooting at the jacal for a full twenty minutes, riddling it with holes from top to bottom.9 One cowboy went to go check if Baca was dead and was shocked to see Baca shooting at him, driving him away towards safety. The cowboys decided to unleash 4,000 shots with the hopes of hitting Baca, with the door itself having at least 400 rounds fired into it. Baca, on the other hand, did not have that type of luxury. Six shooters were usually used with one empty chamber to avoid accidental discharges. If he had fully loaded his Colts, which was uncommon at the time, he would have had 12 rounds. During this time, it was common to wear cartridge belts, which could hold around 20-24 bullets, so Baca would have had at most 36 bullets and at the very least 10 bullets. Against 80 Texan cowboys who could replenish supplies and were not short on ammo, since they could run off and get more without needing to completely stop shooting. Baca shot off about 4-5 rounds before the siege, leaving even fewer bullets. Baca had to count every shot as it could be his last.10

The cowboys were convinced that nobody could survive that onslaught, yet they were wary of Baca and decided that if he was somehow able to survive even after the assault that took place, he would not make it until dawn. What the cowboys did not know was that the floor of the house was actually lower than the rest of the walls of the jacal, meaning that as long as Baca laid completely flat on the floor and no cowboy shot angled down, Baca was untouchable. The cowboys set lookouts to prevent Baca from leaving the jacal during the night and traded posts all throughout the night until dawn, when they got their answer. Baca had started to cook himself breakfast with supplies he found inside the jacal, leaving the cowboys in shock. He was not only alive but unharmed enough to cook breakfast! 11

The cowboys realized that this stalemate could not last forever and decided to once again try to talk Baca into a parley. This, however, did not work, whether it was for a lack of understanding or because Baca did not like the cowboys getting close enough to talk. The parley failed, and the cowboys were getting more and more irritated. They decided to throw burning logs on top of the jacal and even blow it up with dynamite. However, because of the mud roofs and the compactness of the building, this actually did not have the desired effect; the fire did not catch, and the collapsed roof made it harder for the cowboys to access the jacal.12 Throughout the shootout, the inhabitants of Frisco, New Mexico, were getting increasingly concerned, so they reached out to a nearby town to find someone to bring order to this chaos.

Thirty-three hours after the initial shooting, Deputy Sheriff Frank Rose (also spelled in different accounts as Ross) arrived and started to parley with Baca. Quickly realizing Baca did not speak Spanish, Deputy Rose resorted to English and negotiated a truce with Baca. Deputy Rose made both sides put down their guns, yet he allowed Baca to keep his on his person, and promised Baca safe passage towards Socorro for his trial. To ensure no cowboy who had missed the negotiations shot Baca, Deputy Rose had the present cowboys take Baca back to Frisco and wait until Deputy Rose came back and took Baca to Socorro. The cowboys were more than happy to, since they wanted to ask Baca how he managed to survive their onslaught, taking him to the same saloon where Baca had arrested McCarthy, where this entire thing started. Baca explained how he had flattened himself against the floor and, reportedly, one of the cowboys had actually gone and brought back a broom handle that had eight bullet holes in it and reported the entire place was nothing but splinters. Deputy Rose eventually came back and, riding alongside Baca, went towards Socorro for Baca’s trial, which was then moved to Albuquerque. Baca was held in shackles when he entered the court house, but he left a free man, acquitted of all charges, citing self-defense. The lawless Texans no longer ran rampant, and there were no more reported atrocities in Frisco after this event.13 Baca had done what he set out to do; he had stated “that there was at least one Mexican in the country who is not afraid of an American cowboy” and he showed them just that.14

- Ferenc Morton Szasz, “A New Mexican ‘Davy Crockett’: Walt Disney’s Version of the Life and Legend of Elfego Baca,” Journal of the Southwest 48, no. 3 (2006): 263. ↵

- Historical Marker Database, “Elfego Baca Historical Marker,” 2011, Last modified Sept 2015 https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=88497. ↵

- Stan Sager, “One Man, One War: Elfego Baca and His Mission,” New Mexico Bar Journal, 40, (2001): 18. ↵

- Massad Ayoob, “Barricaded: the Elfego Baca story,” American Handgunner (July-August 2015): 46. ↵

- Stan Sager, “One Man, One War: Elfego Baca and His Mission,” New Mexico Bar Journal, 40, (2001): 20. ↵

- Massad Ayoob, “Barricaded: the Elfego Baca story,” American Handgunner (July-August 2015): 46. ↵

- Karra Shimabukuro, “Don’t Just Print the Legend, Write It: ‘The Odd Construction of Elfego Baca as Folk Hero,’” Western Folklore 75, no. 1 (2016): 86. ↵

- Karra Shimabukuro, “Don’t Just Print the Legend, Write It: ‘The Odd Construction of Elfego Baca as Folk Hero,’” Western Folklore 75, no. 1 (2016): 87. ↵

- Stan Sager, “One Man, One War: Elfego Baca and His Mission,” New Mexico Bar Journal, 22. ↵

- Massad Ayoob, “Barricaded: the Elfego Baca story,” American Handgunner (July-August 2015): 46. ↵

- Stan Sager, “One Man, One War: Elfego Baca and His Mission”: New Mexico Bar Journal, 40, (2001): 23. ↵

- Stan Sager, “One Man, One War: Elfego Baca and His Mission”: New Mexico Bar Journal, 40, (2001): 23. ↵

- Stan Sager, “One Man, One War: Elfego Baca and His Mission”: New Mexico Bar Journal, 40, (2001): 24. ↵

- Historical Marker Database, 2012. “Elfego Baca Historical Marker,” (2012), Last modified Sept 2015 https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=88497. ↵

6 comments

Alejandro Rubio Chappell

This was such a wild story—I had no idea who Elfego Baca was before this, but now I’m honestly amazed. The part where he survived 4,000 bullets by lying flat on the floor was insane, and him cooking breakfast the next morning just added to how bold he was. I liked how it all tied back to his promise to stand his ground.

rmanzur

This article was a fascinating read! Elfego Baca’s story was told with great energy and detail—I felt like I was right there in the action. I really enjoyed learning about his courage and resilience. It’s inspiring to see how one person stood their ground and made such a mark on history. Great job bringing his legacy to life!

TJ

Elfego Baca’s story is a remarkable example of courage in a lawless time. At just 19 years old, he confronted a group of violent cowboys in Frisco, New Mexico, after they terrorized the local community. The story highlights how Baca stood his ground, even when faced with overwhelming odds. What stood out to me was his calmness and determination during the standoff, despite being outnumbered and outgunned. His actions show how one person can make a significant difference, even in the most dangerous situations.

Micaella Sanchez

In Elfego Baca’s story, it is crazy to see how his courage challenged not just lawlessness, but also deep prejudice and fear. At only nineteen, he stood up to overwhelming violence and injustice, risking his life to protect a community that the very people he meant to defend had abandoned. His resilience under fire and refusal to back down reminded me that real change often begins with one person refusing to stay silent. Baca’s legacy is more than a tale of survival; it’s a powerful statement about justice, identity, and the strength it takes to confront injustice head-on.

Carlos Flores

Elfego Baca’s legendary stand against the Texan cowboys in 1872 is a testament to his courage and resilience. Despite overwhelming odds, he not only survived a brutal siege but also triumphed over those who underestimated him. Baca proved that one man, armed with determination and skill, could defy injustice and rewrite the history of the Wild West. True heroism. Well written story.

Meadow Ayala

This story was incredible to read — it honestly felt like something straight out of a movie. Elfego Baca’s courage and determination are beyond inspiring. It’s amazing how, even at just nineteen, he stood his ground against overwhelming odds with nothing but grit, smarts, and a whole lot of bravery. His story is a powerful reminder that real heroes often come from the most unexpected places, and sometimes it just takes one person to change everything. I’m so glad stories like this are still being told — they deserve to be remembered.