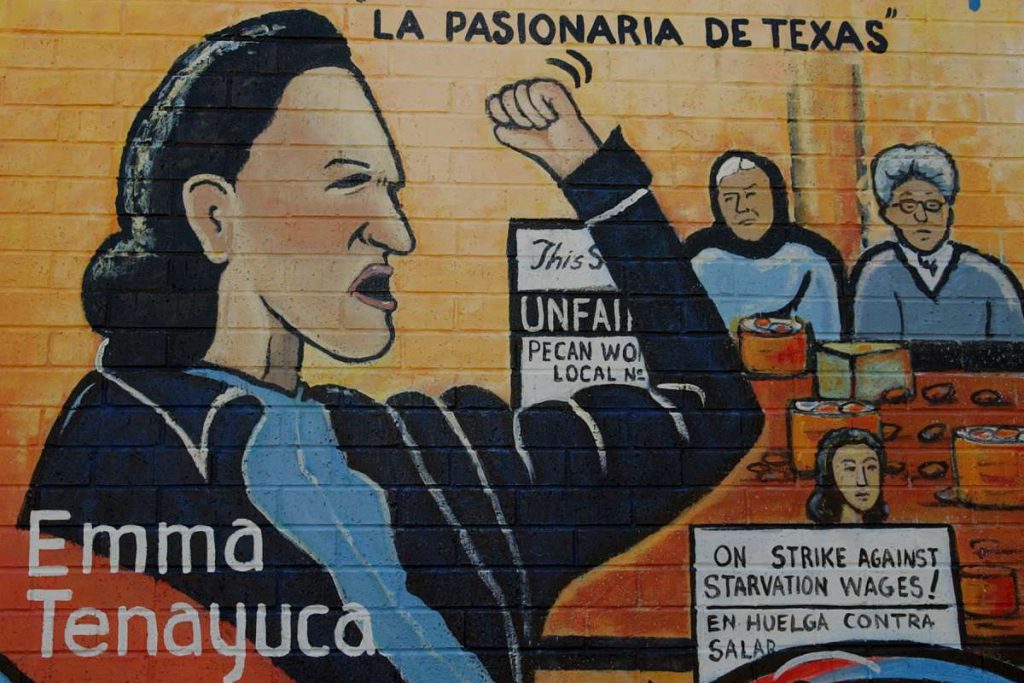

In the middle of a three-month strike, standing there in the crowd of mistreated workers, she was giving them hope, spreading flyers, and organizing picket lines. As she ordered strikers to not make eye contact with the police, the sound of police sirens and firefighters in riot-control gear filled the air. All of a sudden the sizzling sound of tear gas being released was heard in the streets. Those protesting were beaten with clubs, mothers and their children were taken to jail, and Emma Tenayuca was arrested. This would not be the last time she was jailed or met with police force.1

Emma Beatrice Tenayuca was a Mexican American leader, union organizer, and all-around courageous leader. Although she was born on the Southside of San Antonio, Texas, she was raised on the Westside by her grandparents.2 Tenayuca had many successes as a leader of her community despite the uphill battle as a young Mexican-American woman during the 1930s. She went from being a bright student-athlete at Breckenridge High School as a member of the debate, baseball, and basketball teams, to becoming involved in the Fink Cigar company strike of 1933 where she worked with the Workers Alliance of America.3 Her most notable contribution as a leader was the vital role she played in the Pecan Shellers’ Strike of 1938.

The 1930s was a stressful time period for many people across the United States. Although the state of Texas had a booming agriculture-reliant economy, it was no exception to the wrath of the Great Depression and the continuing Dust Bowl.4 San Antonio, Texas was proof of how hard life could be during the 1930s. Although San Antonio has usually been thought of as a beautiful Hispanic cultural hub, that was not always the case. San Antonio, Texas felt the pressure of the Great Depression, the tensions between social classes, and the underlying race issues.5 Mexican-American lives during the 1930s were not immune to these problems. Roughly 1,420,000 Mexican Americans lived in the United States in the year 1930, with three-fourths of that population being in Texas, Colorado, New Mexico, Arizona, and California.6 The Mexican-American people of San Antonio were living testimonies to these issues. The Mexican-American community in San Antonio during the 1930s was subject to exploitative employers, anti-Mexican racism, and the risk of deportation.7 It is easy to imagine how much stress the Mexican-American working-class of San Antonio was under.

San Antonio, Texas in the 1930s also served as the hub for all things pecan. During this time, Texas was responsible for about half of the pecan production of the United States.8 Julius Seligmann, the owner of The Southern Pecan Company, created a profitable business for himself and other owners.9 They exploited the Mexican-American community of San Antonio, many of whom were in dire need of jobs. They used the Mexican-American community as a cheap and expendable source of labor. The pecan shellers grew frustrated over time due to anti-Mexican racism, sexism, and classism that set them back as working-class Mexican-American women. To top it all off, their work as pecan shellers was hard. They had to separate the pecan meat from the shell by hand in badly lit areas. The workstations were benches with no back support. The pecan shellers did not have access to proper toilets or sinks. The pecan shelling created an environment filled with dirt and dust from the pecans. Crowded work areas with particulate matter from other workers combined with the dust only contributed to high rates of Tuberculosis in the city of San Antonio.10 The Mexican-American working-class community of the Westside of San Antonio was being taken advantage of.

On January 31, 1938, about 12,000 pecan shellers walked out from various pecan shelling facilities in San Antonio.11 Fed up with the horrible working conditions and deplorable wages, the pecan shellers, who were mostly Mexican American women of various ages, went on strike for three months. The workers were set off when they learned of a pay cut of about twenty percent of their already low wages.12 Pecan shellers were typically paid about 2-3 dollars a week, or six to seven cents per pound of pecan meat they separated. For the pieces of pecan meat that were not whole, they were paid at about four cents per pound.13 The initial walkout left the pecan facilities with less than 1,000 available workers.14 Tenayuca’s work had already given her a reputation around the city of San Antonio. She was known for her demonstrations, sit-ins, and strikes. The strikers eventually gathered at a local park where they shouted for Emma Tenayuca. The giant crowd of mistreated strikers wanted to have the reputable Tenayuca as their leader. Emma Tenayuca then became the official leader of the Pecan Shellers’ Strike.15 The pecan shellers would later prove that Tenayuca was perfect for the job.

Emma Tenayuca came with full force and lived up to her name. She quickly grew the three-month strike to more than 10,000 workers. She was able to organize all the protesters and help them apply for grants from the (UCAPAWA) United Cannery, Agricultural, Packing and Allied Workers of America, a national workers union.16 With the help of Tenayuca, this strike quickly became one of the largest in the United States. Many protesters and picketers were subject to arrest and harassment by local law enforcement. Tenayuca herself was arrested several times and never stopped fighting.17 Although Tenayuca helped create great strides for the pecan shellers, she received criticism for her communist affiliations at the time. So, Tenayuca was asked to step down from her official position as a leader of the pecan shellers. She complied out of fear of hurting the movement and setting the pecan shellers back. Tenayuca was so committed to the movement and so admired by the working-class community that she remained as an unofficial leader. She continued her work by spreading flyers, organizing picket protests, and setting up soup kitchens. As Tenayuca had earned an image with the Mexican-American working-class community, she also earned an image with the middle class, the Catholic church, and the authorities. Middle-class citizens, both Mexican and Anglo, opposed her activism. Even the Catholic Church opposed Tenayuca and resented the fact that a communist woman was aiding the community.18 From the St. Mary’s University—a Catholic Marianist university—a reporter for the newspaper “The Rattler” reported: “Pecan shellers were yesterday but the targets for the bombastic oratory of fiery little Emma Tenayuca, the local communist leader. Offering, in their utter poverty, a fertile field for sowing the bitter seeds of communism.”19

After drawing enough attention, the Texas Industrial Commission heard the outcry of the pecan shellers and decided to investigate. Two days of hearings to discuss and decide on the pecan sheller’s civil liberties took place. Finally, the Texas Industrial Commission decided in favor of the pecan shellers. The police were no longer allowed to interfere with the peaceful protesting of the strikers and picketers.20 Shortly after, in March of 1938, an agreement was reached between the workers and the company owners, which resulted in a moderate pay increase for pecan shellers. Unfortunately, their struggle did not end. Later in 1938, Congress passed the Fair Labor Standard Act, which created a minimum wage of twenty-five cents per hour. To not pay the workers a fair wage or the minimum wage, pecan shelling companies utilized machines to do the jobs of pecan shellers.21 So, when it was no longer convenient for the pecan shelling companies to exploit the workers, they simply got rid of them. The pecan shellers, along with leaders like Tenayuca, fought hard and deserved better.

As for Tenayuca, after the strike ended in March, things did not go too well for her either. A year later, in 1939, she held a communist party meeting in San Antonio municipal auditorium. Her presence and meeting were not taken lightly that night. Tenayuca and various others in attendance had to be escorted by police due to an angry mob that broke in. Death threats were made on Tenayuca’s life, so she fled the city of San Antonio.22 She settled in the state of California where she earned a teaching degree from the San Francisco State College. She did not return to San Antonio until the 1960s, when she earned a master’s degree in education from Our Lady of the Lake University.23 Even as she fled, she chose to study and become a teacher; she was a Mexican-American leader in many ways.

Emma Tenayuca is a successful activist and leader of the Mexican-American working-class community. Even with the odds stacked against her as a young Mexican-American woman, she still persevered. Although the pecan shellers did not have the happiest of endings, Tenayuca taught them what unity can do, and she gave them hope. Tenayuca was a revolutionary woman who sought to aid her community when no one else would. She was ahead of her time so people used her revolutionary thinking and activism to paint her out as a scary communist. Emma Beatrice Tenayuca has earned her place in the history books and her story deserves to be told.

- Zaragosa Vargas, “Tejana Radical: Emma Tenayuca and the San Antonio Labor Movement during the Great Depression,” Pacific Historical Review 66, no. 4 (1997): 572–574, https://www.jstor.org/stable/3642237 ↵

- Emma Tenayuca, “Interview with Emma Tenayuca,” interview by Jerry Poyo, February 21, 1987, audio, 1:46:02, https://digital.utsa.edu/digital/collection/p15125coll4/id/1170. ↵

- Handbook of Texas Online, 2016, s.v. “Tenayuca, Emma Beatrice 1916-1999,” by Jazmin León and Abigail R. https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/tenayuca-emma-beatrice. ↵

- Carlyn Hammons, “The Great Depression and World War II,” Texas PBS, https://texasourtexas.texaspbs.org/the-eras-of-texas/great-depression-ww2/. ↵

- Rebecca Dominguez-Karimi, “Oral History as a Means of Moral Repair: Jim Crow Racism and the Mexican Americans of San Antonio, Texas,” (PhD diss., Florida Atlantic University, 2018), 51-53. ↵

- Zaragosa Vargas, Labor Rights Are Civil Rights: Mexican American Workers in Twentieth Century America (Princeton University Press, 2008), 16. ↵

- “Immigration and Relocation in U.S. History: Depression and the Struggle for Survival,” Library of Congress, accessed April 5, 2021, https://www.loc.gov/classroom-materials/immigration/mexican/depression-and-the-struggle-for-survival/. ↵

- Handbook of Texas Online, s.v. “Pecan Sheller’s Strike,” by Richard Croxdale, https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/pecan-shellers-strike. ↵

- Arlene Sánchez-Walsh, “Emma Tenayuca, Religious Elites, and the 1938 Pecan-Shellers’ Strike,” In The Pew and the Picket Line: Christianity and the American Working Class (University of Illinois Press, 2016), 147, https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5406/j.ctt18j8xpw. ↵

- Arlene Sánchez-Walsh, “Emma Tenayuca, Religious Elites, and the 1938 Pecan-Shellers’ Strike,” In The Pew and the Picket Line: Christianity and the American Working Class (University of Illinois Press, 2016), 147-148, https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5406/j.ctt18j8xpw. ↵

- Bartee Hailey, “Pecan Shellers Go out on Strike in San Antonio,” Hays Free Press, February 29, 2012. ↵

- Handbook of Texas Online, s.v. “Pecan Sheller’s Strike,” by Richard Croxdale, https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/pecan-shellers-strike. ↵

- Emma Tenayuca, “Emma Tenayuca Oral History Interview,” interview by Luis Torres, 1987-1988, audio, 31:46, https://digital.utsa.edu/digital/collection/p15125coll9/id/11578. ↵

- Handbook of Texas Online, s.v. “Pecan Sheller’s Strike,” by Richard Croxdale, https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/pecan-shellers-strike. ↵

- Bartee Hailey, “Pecan Shellers Go out on Strike in San Antonio,” Hays Free Press, February 29, 2012. ↵

- Handbook of Texas Online, s.v. “Pecan Sheller’s Strike,” by Richard Croxdale, https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/pecan-shellers-strike. ↵

- Arlene Sánchez-Walsh, “Emma Tenayuca, Religious Elites, and the 1938 Pecan-Shellers’ Strike,” In The Pew and the Picket Line: Christianity and the American Working Class (University of Illinois Press, 2016), 161, https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5406/j.ctt18j8xpw. ↵

- Arlene Sánchez-Walsh, “Emma Tenayuca, Religious Elites, and the 1938 Pecan-Shellers’ Strike,” In The Pew and the Picket Line: Christianity and the American Working Class (University of Illinois Press, 2016), 159-160, https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5406/j.ctt18j8xpw. ↵

- Henry A. Guerra, “In Local Emergency as Fellow Catholics Aid Pecan Shellers Facing Starvation,” The Rattler, November 24, 1938, https://texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth841808/ ↵

- Bartee Hailey, “Pecan Shellers Go out on Strike in San Antonio,” Hays Free Press, February 29, 2012. ↵

- Handbook of Texas Online, s.v. “Pecan Sheller’s Strike,” by Richard Croxdale, https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/pecan-shellers-strike. ↵

- David Davies and Yvette Benavides, San Antonio 365 : On This Day in History (Maverick Books, 2020), 188. ↵

- Handbook of Texas Online, 2016, s.v. “Tenayuca, Emma Beatrice 1916-1999,” by Jazmin León and Abigail R. https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/tenayuca-emma-beatrice. ↵

5 comments

Lana Garcia

I absolutely loved this article and the structure of it. Your writing style is beautiful. I love that Emma Tenayuca’s story is being told. Knowing this happened in San Antonio, a Mexican American Women led strike/protest. Very inspiring as a young Hispanic woman, myself. The lesson of the strength in unity, is something our community needed at that time to persevere the numerous challenges they faced.

Hali Garcia

This is such an informative article over a very important and impactful woman. Emma Tenayuca is such an important person in San Antonio and Texas history because of how she helped the Pecan Shellers. The working conditions that the Mexican Americans faced were absolutely horrible and I am glad she stood up for them. What struck me the most was how she stepped down as the leader of the movement so it would not be harmed but she was still viewed as a leader by the people. Great job!

Karla Fabian

Prior to reading this article, I was unaware of Emma Beatrice Tenayuca and her impact. It is very interesting to read how Emma Tenayuca is considered a successful activist and spokesperson of the Mexican-American working class. It is very intriguing to read about her determination, as she had a very tough childhood. It was very sad to read that the pecan shellers did not have a happy ending, even though a lot of work was put into them. But, Tenayuca served as an empowerment figure for them and show them to persevere.

Brittney Carden

Hi Paul, this was a great article that informed me of an event and period of time that I have never been made aware of. Emma Tenayuca was a woman I had not heard of yet, which is a shame. She was a true Latina pioneer and an incredible leader who probably has paved the way for many of us today.

Christopher Metta Bexar

I enjoyed reading this. I just wish the author had covered material I didn’t already know from listening to Dr Van Hoy lecture.

Emma Tenayuca is a fixture in Dr Van Hoy’s courses for a good reason. She was both a role model for Latinas , as well as a leader in the workers rights movement. She was also a complex personality worthy of a longer article (for example how her communist leanings affected her ability to accomplish her dreams for her people).