In 1482, Tomas de Torquemada was informed that King Ferdinand’s campaign was going downhill and was close to failing. The King’s army kept on getting smaller each day; they were dying of diseases, and they were low on food and weapons. Torquemada heard what was happening and decided to help out by sending gold. However, by the time it got there, it was too late for them to use it. Although they did not get it in time, his action did not go unnoticed, and it was soon going to pay off, since he proved his loyalty to Ferdinand and Isabella. This was the start of a great friendship.1

In 1478, the Queen had requested the authority to create an inquisition in Castile, but the Pope did not give his blessing until 1480. The Pope’s only regulation was that it needed to be run by a bishop and that there would be no more than two or three Inquisitors. With the Pope’s blessing and the strong persuasion of Isabella, Torquemada was appointed the first inquisitor general of Castile in 1483. A few days later, his appointment began in Seville and then spread all the way to Aragon and Catalonia, which he remained in charge of for the rest of the Inquisition’s history.2 From this moment, the Inquisition became a major fear for all conversos. They didn’t know who was going to be convicted, so people lived in fear for many years. In the first year, twenty-seven people were convicted of Judaizing, which led them to be burnt, and 3,300 were penanced.3 Throughout Spain, people were being convicted, and no one was safe. At first, they gave them a thirty-to-forty-day period in which anyone who would come forward to confess would be free from any threat. But people didn’t take advantage of this time since they were either embarrassed or they just weren’t sure if what they were practicing was considered wrong. In 1484, Torquemada oversaw mass trials in Seville. The conversos lived in fear because they were exposed to accusations that led to arrest and imprisonment. They would be accused with evidence that came from faceless accusers. Many fled their native cities, others were ready to fight, and many locals settled down to wait for this obstruction.4

On August 16, 1486, the first auto-da-fe took place. Torquemada brought up twenty men and five women who were accused of practicing Judaism and were placed in the Inquisition prison. It started around six o’clock in the morning. The first thing they would do was announce each person’s name, then they would wrap a rope around their neck. After this, they would walk through the streets until they ended up with a priest to celebrate Mass.5 Throughout the Mass, the prisoners were on their knees, and before the Mass ended, they would say the sins of each person accused. The prisoners who had gotten the penalty of being abandoned to the secular arm were exhorted to repent and make their peace in the church. While that was happening to some of the accused, the others would be brought up one by one to sit on a stool while they would read the sentence they got, while everyone watched. This took about six hours; it wasn’t over until noon, and the last step to complete the whole process was the hurrying away to La Dehesa of the last of those twenty-five.6 The responsible party (the bishops) turned a blind eye when it came to the Inquisition of Torquemada with the exception of one bishop who spoke up and tried to explain how these harsh punishments they were inflicting on the people were wrong.7 A priest even spoke up during this time and stated how God wanted the sinner to have a consequence, but burning the sinner earlier than that would be cheating God. This is why, when an auto-da-fe takes place, it lasts almost an entire day. This made many people realize how men could change the way they think to justify the practices of the Holy Office.8

While Torquemada was leading the Inquisition, he was learning many things and gaining ideas from a manual created in 1320. This manual was divided into five parts. The first three parts were about procedures and tips for every occasion in an Inquisition, which included citation, arrest, pardon, commutation, and sentence. The fourth part explained the power vested in the tribunal of the Inquisition. The fifth part explains the beliefs of Gui’s day and the ceremonies by which it laid down methods. Although there weren’t many copies in the beginning of the Inquisition, however, by the time Torquemada was in charge, there were many copies being distributed.9 In the late 1480’s Torquemada urged the monarchs to expel all Jews from Zaragoza; he claimed they had violated certain privileges and were threatening Spain. Although they started enforcing Jews to leave the pressure from the Christian community, it had been going on since 1477. In Soria, a royal order was sent to permit the relocation of the Jewish community to an area where they did not have access to others. With all these different relocation problems, the monarchs decided to declare a general segregation law. What was supposed to calm society’s anxiety by making Jews less visible was, in fact, the first step in the destruction of Jewish communities. The first thing they decided was that Jews had to live in specific quarters, which meant many property owners raised the prices an unreasonable amount. In 1481, they made all Jews live in a new ghetto, and this is where they remained until 1488.10 Throughout this time, they started to limit convenience stores, which meant they only had one store they could shop at. Then they prevented Jews from purchasing fish on Fridays. After some time passed, they eventually started taking away necessities like coal, wood, and baked bread. Although many royal counselors were worried that by pushing the Jews too much, it wasn’t only going to hurt them but also possibly hurt the economy. When Torquemada heard these concerns, he stated how faith is more important than material loss, and this is what they had chosen for themselves. With all these changes to the residents, the raising of taxes, and the discrimination against residents, Torquemada took this as an opportunity to push the king and queen to write the decree.11 All this pressure got to Ferdinand and Isabella, which led them to issue the edict of Expulsion of all Jews. This was the third and final stage since all Jews were expelled from the entire region. Although Ferdinand and Isabella did everything in their power to avoid this, they at last had to acknowledge the de facto banning of the Jews from Castilian life and command the mass expulsion. Thousands of Jews had no choice but to sell their land and leave all their belongings behind.12 Spain was culturally reduced; however, its reputation was stained for centuries to come.13

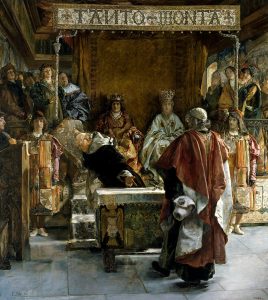

Francisco Padills’ 1888 painting represents Tomas de Torquemada consulting with Spanish monarchs. Their influence eventually led to the policies of the Spanish Inquisition, including the expulsion of Jews in 1492.

The expulsion of the Jews was the peak moment in Torquemada’s life; it was his biggest achievement. As time went on, his power decreased, and he went back to not having power or importance. But his enemies were increasing in Spain at an alarming rate because they never forgot all the damage he had caused.14 People with high power in churches, including the Archbishop of Messina, Martin Ponce de Leon, Bishop of Cordova, Don Inigo Manrique, and Bishop of Avila, Don Francisco Sanchez de la Fuente, tried to take the power Torquemada had by making their opinions obvious, which was that they never agreed with him and thought everything he did was wrong. They brought up how out of the four Inquisitors appointed, only two accepted offices with Torquemada, which proved that not many people were on his side to begin with. However, Torquemada remained the guiding spirit of the Holy Office in Spain.15

In 1496, Torquemada made his exit from the Court, where for a decade he had been a figure of importance, second only to that of the Sovereigns themselves. After all the damage he had done for years, he finally withdrew to his monastery at Ayala. There he lived out his retirement, a wasted old man with body infirmities, alone, but with calmness and at peace with everything he had done in the Inquisition, and he gave his best for the service of God. Although he was retired, he was still focused on the Inquisition. On May 25, 1498, the fourth “instructions” of Torquemada was published. It contained a good deal that seems calculated to soften the rigor of the earlier decrees, yet much of this is more or less illusory. In addition, he also published sixteen articles that same year, which were special instructions concerning the personnel of the Holy Office. The articles spoke for themselves, as they vividly suggest the abuses they were framed to conquer.16 Tomas de Torquemada soon passed away in his monastery of St. Thomas at Avila. He passed away peacefully and relieved because he had accomplished everything he wanted. His honesty and judgment were what many people believed were the reasons for him to be such an evil and cruel man. He was anything but a saint.17 This Inquisition became a horrible nightmare for Jewish people; he was no hero but was a man who was evil and horrible.

- Stephen H. Haliczer, “The Castilian Urban Patriciate and the Jewish Expulsions of 1480-92,” The American Historical Review 78, no. 1 (1973): 37. ↵

- Norman Roth, “The Jews of Spain and the Expulsion of 1492,” The Historian 55, no. 1 (1992): 25. ↵

- Rafael Sabatini, Torquemada and the Spanish Inquisition. A History. With a Photogravure Frontispiece and Fifteen Other Ills in Half-Tone, Including a Map (Paul, 1913), 256. ↵

- Stephen H. Haliczer,“ The Castilian Urban Patriciate and the Jewish Expulsions of 1480-92,” The American Historical Review 78, no. 1 (1973): 43. ↵

- Rafael Sabatini, Torquemada and the Spanish Inquisition. A History. With a Photogravure Frontispiece and Fifteen Other Ills in Half-Tone, Including a Map (Paul, 1913), 247, 248. ↵

- Rafael Sabatini, Torquemada and the Spanish Inquisition. A History. With a Photogravure Frontispiece and Fifteen Other Ills in Half-Tone, Including a Map (Paul, 1913), 250, 251, 252. ↵

- Rafael Sabatini, Torquemada and the Spanish Inquisition. A History. With a Photogravure Frontispiece and Fifteen Other Ills in Half-Tone, Including a Map (Paul, 1913), 169. ↵

- Rafael Sabatini, Torquemada and the Spanish Inquisition. A History. With a Photogravure Frontispiece and Fifteen Other Ills in Half-Tone, Including a Map (Paul, 1913), 223. ↵

- Rafael Sabatini, Torquemada and the Spanish Inquisition. A History. With a Photogravure Frontispiece and Fifteen Other Ills in Half-Tone, Including a Map (Paul, 1913), 139. ↵

- Stephen H. Haliczer, “The Castilian Urban Patriciate and the Jewish Expulsions of 1480-92,” The American Historical Review 78, no. 1 (1973): 52, 53. ↵

- Stephen H. Haliczer, “The Castilian Urban Patriciate and the Jewish Expulsions of 1480-92,” The American Historical Review 78, no. 1 (1973): 55. ↵

- Stephen H. Haliczer, “The Castilian Urban Patriciate and the Jewish Expulsions of 1480-92 ” The American Historical Review 78, no. 1 (1973): 58. ↵

- Norman Roth, “The Jews of Spain and the Expulsion of 1492 ” The Historian 55, no. 1 (1992): 30. ↵

- Rafael Sabatini, Torquemada and the Spanish Inquisition. A History. With a Photogravure Frontispiece and Fifteen Other Ills in Half-Tone, Including a Map (Paul, 1913), 377, 378. ↵

- Rafael Sabatini, Torquemada and the Spanish Inquisition. A History. With a Photogravure Frontispiece and Fifteen Other Ills in Half-Tone, Including a Map (Paul, 1913), 383, 384. ↵

- Rafael Sabatini, Torquemada and the Spanish Inquisition. A History. With a Photogravure Frontispiece and Fifteen Other Ills in Half-Tone, Including a Map (Paul, 1913), 385, 386. ↵

- Rafael Sabatini, Torquemada and the Spanish Inquisition. A History. With a Photogravure Frontispiece and Fifteen Other Ills in Half-Tone, Including a Map (Paul, 1913), 392. ↵

9 comments

Rita Uresti

Great article April! Very well written and you helped me learn something new this week.

Esther Ortega

Thank you for capturing the horrible actions of Torquemada. Very well written and organized!

Micaela

The article was very interesting and informative. The author did an excellent job in providing her readers a clear and vivid picture about type of person Tomas de Torquemada was and all the damages he caused over the years, especially in regards to the Jews and converos. Yay, April!

Susie

The writing is vivid and emotionally impactful, especially when describing the fear and suffering experienced under Torquemada’s rule. A great blend of historical detail with storytelling. The article is well-organized and flows smoothly from beginning to end. Great job April!

Alita Uresti

April, this was really good. You made everything about Torquemada super easy to understand, was very well organized, and it was really interesting to read. Love seeing you kill it with your writing like always.

Albert U

Very well thought out and written article. Thanks for sharing your knowledge on such an important topic in the world’s history.

Hector

Wow that’s a really good overview of the Inception of the Inquisition. There’s probably a lot of history there that could be researched but that definitely Peaks the interest of somebody who has Heritage from Spain and France and whose DNA came back almost 20% Jewish. I guess at a certain point people deemed it more important to stay alive and denounce their faith than to die in their faith. As someone going in to Christian Ministry I hope I’m never faced with that decision

Byanca

After reading this article I have gather new information about Tomas de Torquemada. It is well written and organized and gives a new perspective on how there are different point of views to each person that has made a difference and how it has shaped our history.

Lisa Elizabeth

Well written and very informative; the author captured, in a simple way, the wickedness of Torquemada and how one person could have so much influence over a whole people, in this case the Jews; good job, April