Harriet Tubman crossed the Mason-Dixon line into Pennsylvania and freedom after an arduous journey—alone—accomplished with courage and skill. Once in Pennsylvania, Tubman later admitted to biographer Sarah Bradford, “when I found I had crossed that line, I looked at my hands to see if I was the same person. There was such a glory over everything; the sun came like gold through the trees, and over the fields, and I felt like I was in Heaven.” Yet, she continued, her freedom was not without apprehension. “I had crossed the line. I was free, but there was no one to welcome me to the land of freedom. I was a stranger in a strange land.”1 According to historian Kate Clifford Larson, Harriet Tubman “runs away twice in the fall of 1849 after hearing she might be sold to pay Brodess’s debts. She successfully reaches freedom in Philadelphia on her second try”2 In December of 1850, Tubman conducted her first rescue mission by coordinating the escape of her niece Kessiah Jolley Bowley and Kessiah’s two children, James Alfred and baby Aramita, through the assistance of Kessiah’s free husband, John Bowley. Harriet Tubman was not content with just liberating herself. Despite stepped-up efforts to halt escaping slaves in Dorchester County, Tubman was compelled to return to the Eastern Shore to help lead other enslaved people to freedom. Several months after her escape, she aided John Bowley, his wife, and two small children in finding sanctuary in Baltimore among abolitionist friends. Several months later, Tubman returned again to Baltimore from her safe house in the North to help her brother Moses and two other men escape to freedom.3 She had created a life for herself in Philadelphia, where she found work and began to connect with the abolitionist movement. She worked with other abolitionists like Frederick Douglass and William Still, helping to raise awareness about the horrors of slavery and advocating for its end.

This story unfolds in the 1850’s, at a time when America had been a unified nation for nearly eighty years, but the country was still deeply divided over the institution of slavery. First, there was slavery which played a central role in the growing sectional tensions between the North and the South, as the Southern states relied heavily on enslaved labor to sustain their agricultural economy. The institution of slavery had been deeply ingrained in the economic fabric of the South, where the vast majority was characterized by plantations and staple crops such as rice, sugar, and cotton. But with the beginnings of rice cultivation, that changed dramatically. Rice required intensive labor under the grimmest of conditions.4 Then there were sectional tensions; this reliance on slavery not only shaped the region’s economy but also fueled sharp political and social divisions with the free states of the North, where slavery was increasingly viewed as morally unacceptable. By1820, those tensions had reached a boiling point when Missouri applied to join the United States as a slave state. A temporary solution emerged when Senator Henry Clay of Kentucky brokered a solution to the crisis. The resulting Missouri Compromise stipulated that Missouri would be admitted to the union as a slave state. In contrast, Maine, which had petitioned for statehood in late 1819, was admitted as a free state. The compromise also prohibited slavery from the remainder of the Louisiana Territory in the area north of 36°30′ north latitude, while permitting it south of that line. Between 1820 and 1848, this solution maintained national peace, as the Senate remained balanced with thirty members representing the free states and an equal number representing the slave states.5

Harriet Tubman, now living as a free woman in the North, was finally experiencing the freedom she had fought so hard to claim. But now she had a new expedition: to free her brothers. Tubman was already used to traveling to the South, but this news gave her an even greater reason to act once again. The urgency of saving her brothers increased her desire that she was already building up to free others from the chains of enslavement. The journey to return to the South, where her previous life was, would not be easy. Every trip she would conduct would mean putting her life in danger because of the risk of capture, death, or being returned to slavery. But Harriet wasn’t one to back down. She knew the dangers, and yet her resolve was set in stone. This would be another one of her trips to the South, navigating through hostile terrain and constantly evading slave catchers. It was as if the world was against Tubman but her goal was set; she was going back to Maryland for her brothers to help them escape using the Underground Railroad and bring them to a free state safely, without getting caught or killed. There was no turning back. Harriet was smart, and she understood what was at stake, not just for her brothers, but for herself and every enslaved person yearning for freedom. She was willing to risk everything, even knowing the dangers that lay ahead. For her family, for herself, and for the countless others suffering under the cruelty of slavery, Harriet was prepared to give everything to advance this mission. Driven by love and a sense of justice, this would mark the beginning of her legendary role as one of history’s most courageous freedom fighters, forever changing the course of her life and the lives of many others.

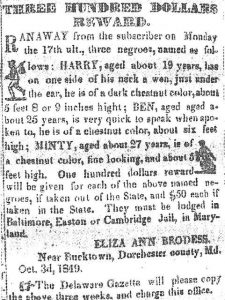

This wouldn’t be the first time her brothers had attempted to escape with Harriet in the past. On March 7, 1849, Edward Brodess, her white owner, died, leaving his widow Eliza burdened with debt and six of their eight children dependent upon her. She began selling some of her enslaved people.6 With the uncertainty surrounding the Brodess family’s disposition of its slaves, Harriet Tubman, along with her brothers Henry, Robert, and Ben, set out to escape enslavement with the fear of being sold and take a path north to freedom. Eliza Ann Brodess, the wife of their white owner, placed an advertisement in the Delaware Gazette announcing a reward for the return of Harriet Tubman and her brothers along with a description of each of them. There would be a $100 reward for each slave and they must be lodged in Baltimore, Easton, or Cambridge Jail in Maryland. With the fear of them getting caught, the brothers decided to turn back to the Brodess plantation.7 Fearing the consequences of running away if they were caught, the brothers decided to return to the Brodess plantation.8 Now five years later, Harriet got news that her brothers were to be sold to new owners immediately after the holidays. They would be torn from their families, separated forever, and still slaves. Harriet Tubman returned to Maryland to free Ben, Robert, and Henry, where they were to be enslaved at the Thompson Farm in Poplar Neck in Caroline County.9

In the mid-nineteenth century, Christmas was considered the ideal time for slaves to make their escape. It was the only period when they were granted an extended break from their labor, and many were even given passes to visit family members living on nearby plantations. These passes provided slaves with the rare and unusual privilege of being allowed to travel on the roads unaccompanied, a freedom they almost never experienced at any other time.10 Seizing this opportunity, Harriet’s brothers, along with other family members, were able to use these passes to slip away from the plantation undetected. They met up with Harriet at a prearranged location, where they took shelter in a corn house, waiting for several hours. As soon as nightfall arrived, they began their dangerous journey towards freedom, knowing the risks that lay ahead but determined to escape the bonds of slavery for the greater good. On this trip, Harriet traveled at night with a group of rescued men, women, and children, in this case, her brothers, guided by the stars and her intimate knowledge of the topography of the region. Traveling by dark and avoiding main roads, Tubman was able to lead groups of varying sizes, according to her own description, “over mountains, through forests, across rivers, mid perils by land, perils by water, and perils from enemies.” Usually, the groups moved on foot and kept up a grueling pace that exhausted Tubman’s charges until they dropped from fatigue at dawn.11 Tubman’s escape was certainly not for the weak as the journey was extremely exhausting and physically demanding. Additionally, during the daylight hours, Tubman would leave her party in a dense wood while she visited one of the stations on the Underground Railway, as she referred to it. There she would purchase food for her group and obtain any local intelligence regarding slave catchers in the area. She would then return to her runaways, signaling her approach by singing a hymn as a way of announcing an all-clear. As noted previously, singing hymns allowed Tubman to signal either an all-clear or, by changing the lyrics, potential danger.12 This technique also gave Tubman cover for her own safety if she were approached by anyone who was a “false brethren.” She would be perceived as an innocent slave singing hymns as she conducted errands for her master. One of the hymns Tubman frequently sang was, “Around him are ten thousand angels. Always ready to obey his command. They were always hovering round you, till you reach the heavenly land.”13 Tubman was extremely clever when it came to hiding her tracks. Harriet had to be constantly vigilant throughout her journey, avoiding anyone who might betray her. At the time, there was widespread hatred and racism towards African Americans in America, which made it crucial for her to exercise extreme caution. Traveling over 100 miles over the course of many days, they finally arrived at William Still’s Anti-Slavery Office in Philadelphia on December 29, 1854. Tubman succeeded in rescuing her three brothers on Christmas Day, bringing them to freedom in Philadelphia and then to St. Catherine’s, Ontario, Canada.14

After making it back Philadelphia, Ben, Robert, and Henry were going to be taken in by members of the free Black community and abolitionist networks under William Still. Luckily, they were in good hands. William Still and a few other abolitionists had just created a new vigilance committee with an improved agenda where they would have the authority to attend “to every case that might require their aid,” to raise necessary funds, and to “keep a record of all their doings,” and especially of their receipts and expenditures with William Still as their appointed chairman of acting committee.15 However, with the enactment of the Fugitive Slave Act on September 18, 1850, they were forced to exercise greater caution. This new law, backed by the government, mandated the return of escaped slaves to their owners, even if they had reached free states like Pennsylvania.

One of the principal activities of the new Philadelphia Vigilance Committee was to extend financial aid to fugitives. The committee provided money to board fugitives with families of free Negroes, sometimes for as long as thirteen days but usually only for a few days. The community purchased clothing, medicine, and fugitives’ railroad fares to Canada.16 This would be the next step, for Ben, Robert, and Henry Tubman would spend their time and eventually flee to Canada because of the troubles with the Fugitive Slave Act. Her brothers shed the Ross surname and took the new name “Stewart” for protection purposes.17 With her brothers safe and taken care of, Harriet’s work was far from finished. She couldn’t rest, not while so many others still needed her help. Her determination hadn’t wavered. It had only grown stronger. Harriet was deeply committed, driven by a sense of purpose and a desire for change that wouldn’t let her quit. She knew there were more lives to save, and she wasn’t about to stop now. Each rescue fueled her resolve, pushing her to keep going, knowing that every person she freed brought her closer to the dream of freedom for all.

- ROBERT C. PLUMB and Elisabeth Griffith, “The Underground Railroad,” in The Better Angels, Five Women Who Changed Civil War America (University of Nebraska Press, 2020), 42. ↵

- Kate Clifford Larson, “Harriet Ross Tubman: Timeline,” Meridians 12, no. 2 (2014), 11. ↵

- ROBERT C. PLUMB and Elisabeth Griffith, “The Underground Railroad,” in The Better Angels, Five Women Who Changed Civil War America (University of Nebraska Press, 2020), 43 ↵

- Jane Landers, “Slavery in the Lower South,” OAH Magazine of History 17, no. 3 (2003), 24, 25 ↵

- John G. Clark and E. A. Reed, “Compromise of 1850,” Salem Press Encyclopedia, April 30, 2023, 1. ↵

- Kate Clifford Larson, Harriet Tubman : A Reference Guide to Her Life and Works, Significant Figures in World History (Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2022), xvii. ↵

- ROBERT C. PLUMB and Elisabeth Griffith, “The Underground Railroad,” in The Better Angels, Five Women Who Changed Civil War America (University of Nebraska Press, 2020), 41. ↵

- ROBERT C. PLUMB and Elisabeth Griffith, “The Underground Railroad,” in The Better Angels, Five Women Who Changed Civil War America (University of Nebraska Press, 2020), 41. ↵

- Kate Clifford Larson, Harriet Tubman : A Reference Guide to Her Life and Works, Significant Figures in World History (Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2022), xxiv ↵

- Philander D. Chase, Private Lives of Slaves | George Washington’s Mount Vernon (Charlottesville, VA: University Press of Virginia, 1987), 1. ↵

- ROBERT C. PLUMB and Elisabeth Griffith, “The Underground Railroad,” in The Better Angels, Five Women Who Changed Civil War America (University of Nebraska Press, 2020), 33 ↵

- ROBERT C. PLUMB and Elisabeth Griffith, “The Underground Railroad,” in The Better Angels, Five Women Who Changed Civil War America (University of Nebraska Press, 2020), 33. ↵

- ROBERT C. PLUMB and Elisabeth Griffith, “The Underground Railroad,” in The Better Angels, Five Women Who Changed Civil War America (University of Nebraska Press, 2020), 34. ↵

- Kate Clifford Larson, “Harriet Ross Tubman: Timeline,” Meridians 12, no. 2 (2014), 13. ↵

- Larry Gara, “William Still and the Underground Railroad,” Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies 28, no. 1 (1961), 34. ↵

- Larry Gara, “William Still and the Underground Railroad,” Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies 28, no. 1 (1961), 34-35 ↵

- Kate Clifford Larson, Harriet Tubman : A Reference Guide to Her Life and Works, Significant Figures in World History (Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2022), xvii. ↵

6 comments

Freya Hayes

This article was very well written. It told a very interesting story about Harriet Tubman’s fight for freedom in a fun way. I learned about the principle activities of the Philadelphia Vigilance Committee and how they aided the brothers who had found freedom. I really enjoyed the way this article was laid out and how easy it was to follow through the story being told. The article was very well written and the visuals added to the story. If I could ask a question it would be the motivation for this article to be written and how the author connects to this piece of history. Overall this article was very well written and filled with numerous facts.

Danielle Villanueva

This powerful article truly illuminates Harriet Tubman’s incredible courage and strategic brilliance in helping enslaved people escape to freedom. I was struck by her remarkable resilience and how she risked her own life repeatedly to rescue her family and others. The detailed descriptions of her dangerous journeys and the historical context of slavery in America made the story both heartbreaking and inspiring. I wondered: How did Tubman maintain such extraordinary emotional strength during these perilous missions?

Vivian

Very interesting article about ending her brother’s suffering. The story was well written and fun to read. Thank you for this.

Victoria

Your paper on Harriet Tubman offers a compelling exploration of her courage, resilience, and enduring impact on history. It powerfully highlights her contributions to the fight for freedom and justice, making her legacy feel even more relevant today. Great work!

Augustine

“Captivating and very educational article!” I enjoyed reading about Harriet Tubman’s commitment to help her family acquire Freedom.

Ester

Well written article about Tubman’s commitment and desire for change. “Interesting and engaging!”