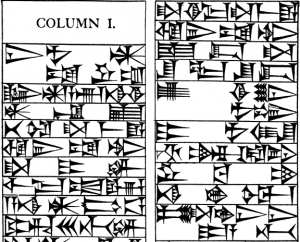

The Code of Hammurabi is among the most influential collection of laws that has even continued to be recognized to the present.1 Upon closer examination, however, these laws treated and punished the women of Babylonian society more harshly in comparison to the men. Many scholars who have examined and analyzed the Code of Hammurabi would agree that women, although having played such an essential role in ancient societies, were treated as mere property while men held all the power. Some have addressed that the laws in general were already pretty harsh, in having death penalties for many of the crimes.2 Other scholars address more specifically the patriarchal practices societies in ancient Babylonia practiced. From a sociological perspective, the power that was given to the men indicated a corresponding subordination for the women. So, although the time of Hammurabi could be seen as one in which an ancient economy flourished, some authors would agree that there were societal standards that hindered women from achieving greater power.3 From a broader perspective, there are great debates about the perception of women in biblical and ancient near eastern law. Pamela Barmash discusses how, despite women holding an inferior status in comparison to men, most of their rights were protected by the law. Barmash even claims that some were able to improve their status through influence. However, she also acknowledges the inequity in punishments between me and women, and blames the inequality seen between men and women in laws from the Bible.4 Through Hammurabi’s Code, women were treated a lot harsher than men when it came to things like leaving a marriage, adultery, and incest. Although Hammurabi, through his laws, attempted to ensure that the laws applied to everyone, those that specifically addressed women were far more cruel and punishing for either the same crimes or crimes of less severity than on men.

In most ancient societies, and specifically among societies in ancient Mesopotamia, marriage and bearing children was the most important thing a woman could do. However, marriage back then looked a lot different from what we think about marriage today. M. Stol writes about how girls were usually married between the ages of fourteen and twenty, while men married between the ages of twenty-six and thirty-two.5 This is a fundamental gap between the two that contributed to a man’s sense of superiority over a woman. Not only were they younger, but the parents of the girls would decided who they would marry. Scholars have also compiled what a “normal” marriage would look like during this time. This included, but was not limited to, the man having the right to acquire a concubine and not only could he have a concubine, but if his wife did not bear him children, he would be able to demote his wife and promote his concubine to his wife.6 Furthermore, as a society, people believed that the only way for a woman to become respectable was for her to bear her husband children. However, in order to protect a man’s inheritance, more and more restrictions were placed on women in order to keep track of the paternity of children; this led to the enforcement of patriarchal practices.7 With this in mind, we turn to look at how women were thus perceived in the law and more specifically, in the Code of Hammurabi.

As previously mentioned, marriage for a woman in ancient Babylonia was their life goal, so it became even more difficult for women than it was for men to leave a marriage. Typically, if a man wanted a divorce, he would have to pay between 10-20 shekels of silver. However, if a woman were to say that her husband was no longer her husband, she would be tied and thrown into the river to drown.8 In the Code of Hammurabi, the law states: “If a man wish to separate from a woman who has borne him children, or from his wife who has borne him children: then he shall give that wife her dowry, and a part of the usufruct of field, garden, and property, so that she can rear her children. When she has brought up her children, a portion of all that is given to the children, equal as that of one son, shall be given to her. She may then marry the man of her heart.”9 It gets somewhat more complicated for the women. The Code of Hammurabi states: “If a woman quarrel with her husband, and say: ‘You are not congenial to me,’ the reasons for her prejudice must be presented. If she is guiltless, and there is no fault on her part, but he leaves and neglects her, then no guilt attaches to this woman, she shall take her dowry and return back to her father’s house.”10 The major difference we see here is that the woman has to prove herself in order to leave a marriage she no longer wishes to be a part of. To make matters worse, the law also states: “If she is not innocent, but leaves her husband, and ruins her house, neglecting her husband, this woman shall be cast into the water.”11 There are copious instances in which a man can, as mentioned earlier, acquire a concubine, or even be gifted a servant by his wife; and in these cases, the law does not list it as adultery, nor is there a punishment for it. Additionally, matters became somewhat more complicated when a man was captured as a prisoner of war. In these cases, the situation varies; the law states: “If a man is taken prisoner in war, and there is sustenance in his house, but his wife leave house and court, and go to another house: because the wife did not keep her court, and went to another house, she shall be judicially condemned and thrown into the water.”12 However, the law also states that “If any one be captured in war and there is no sustenance in his house, if then his wife got to another house and this woman shall be held blameless.”13 In these cases, it really depends on whether there was sustenance in the home; however, we still see a punishment for the woman for essentially trying to find another way to survive.

Adultery was also a crime with a double standard punishment. Most scholars have said that men would often take in a second wife if his first had not borne him children.14 Women, on the other hand, were usually not able to be with another man without serious repercussions. The law of Hammurabi states: “If a man’s wife be surprised (in flagrante delicto) with another man, both shall be tied and thrown into the water, but the wife is blameless.”15 Here we see that even though the wife is blameless, she is punished with a cruel death. Another example of this is: “If the ‘finger is pointed’ at a man’s wife about another man, but she is not caught sleeping with the other man, she shall jump into the river for her husband.”16 Despite not being guilty of adultery, the woman must give her life for her husband simply because she was accused. On the other hand, Hammurabi’s Code states: “If a man take a wife, and she bear him no children, and he intend to take another wife, if he takes a second wife, and bring her into the house, this second wife shall not be allowed equality with his wife,” as well as “If a man take a wife and she give this man a maid-servant as wife and she bear him children, and then this maid assume equality with the wife: because she has borne him children, her master shall not sell her for money, but he may keep her as a slave, reckoning her among the maid-servants.”17 The idea of the patriarchy is largely seen through these laws as men had the freedom to partake in monogamous marriages and had absolute power over the household.

Lastly, although there is not much research about how these ancient societies partook in and perceived incest, there are some laws in the Code of Hammurabi that mention the punishment for it. Once again, we see this double standard in the punishment for men and women. The code states: “If a man be guilty of incest with his daughter, he shall be driven from the place (exiled).” The code also states “If any one be guilty of incest with his mother after his father, both shall be burned.”18 This serves to prove that although it was the same crime, the punishment is different for the dynamics of father/daughter and mother/son.

Even though women in ancient Mesopotamia were allotted some power, it never came near to that of men. Even if women did work, they only received half the payment that a man would receive.19 Scholars have been most surprised with the woman’s ability to show resilience despite the harsh laws imposed on them and more so the heavy influence of patriarchy. Although these are only some of the instances in which women received more cruel punishment, it shows clearly how there was a double standard when it came to men and women. Even more so, it shows that women, during the Code of Hammurabi, were punished more severely for the same crimes and even crimes of lesser gravity.

- John Bankston, Hammurabi (Slovenia: Mitchell Lane, 2018): 33. ↵

- John Bankston, Hammurabi (Slovenia: Mitchell Lane, 2018): 33. ↵

- George Vincent, “The Laws of Hammurabi,” The American Journal of Sociology, Vol. 9, No. 6 (1904): 746. ↵

- Pamela Barmash, “Women in Biblical and Ancient Near Eastern Law,” Religion Compass, Vol. 12, No. 5-6 (2018): 6. ↵

- M. Stol, “Women in Mesopotamia,” Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient, Vol. 38, Issue 2 (1995): 125. ↵

- M. Stol, “Women in Mesopotamia,” Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient, Vol. 38, Issue 2 (1995): 125. ↵

- Margaret Crocco, Nadia Pervez, Meredith Katz, “At the Crossroads of the World: Women of the Middle East,” The Social Studies, Vol. 100, Issue 3 (2009): 108. ↵

- M. Stol, “Women in Mesopotamia,” Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient, Vol. 38, Issue 2 (1995): 130. ↵

- L.W. King, Ancient History Sourcebook the Code of Hammurabi, c. 1780 BCE (Champaign, IL., Project Gutenburg, 1998): 24. ↵

- L.W. King, Ancient History Sourcebook the Code of Hammurabi, c. 1780 BCE (Champaign, IL., Project Gutenburg, 1998): 24. ↵

- L.W. King, Ancient History Sourcebook the Code of Hammurabi, c. 1780 BCE (Champaign, IL., Project Gutenburg, 1998): 24. ↵

- L.W. King, Ancient History Sourcebook the Code of Hammurabi, c. 1780 BCE (Champaign, IL., Project Gutenburg, 1998): 24. ↵

- L.W. King, Ancient History Sourcebook the Code of Hammurabi, c. 1780 BCE (Champaign, IL., Project Gutenburg, 1998):24. ↵

- M. Stol, “Women in Mesopotamia,” Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient, Vol. 38, Issue 2 (1995): 129. ↵

- L.W. King, Ancient History Sourcebook the Code of Hammurabi, c. 1780 BCE (Champaign, IL., Project Gutenburg, 1998): 23. ↵

- L.W. King, Ancient History Sourcebook the Code of Hammurabi, c. 1780 BCE (Champaign, IL., Project Gutenburg, 1998): 24. ↵

- L.W. King, Ancient History Sourcebook the Code of Hammurabi, c. 1780 BCE (Champaign, IL., Project Gutenburg, 1998): 24-25. ↵

- L.W. King, Ancient History Sourcebook the Code of Hammurabi, c. 1780 BCE (Champaign, IL., Project Gutenburg, 1998): 25. ↵

- M. Stol, “Women in Mesopotamia,” Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient, Vol. 38, Issue 2 (1995): 137. ↵